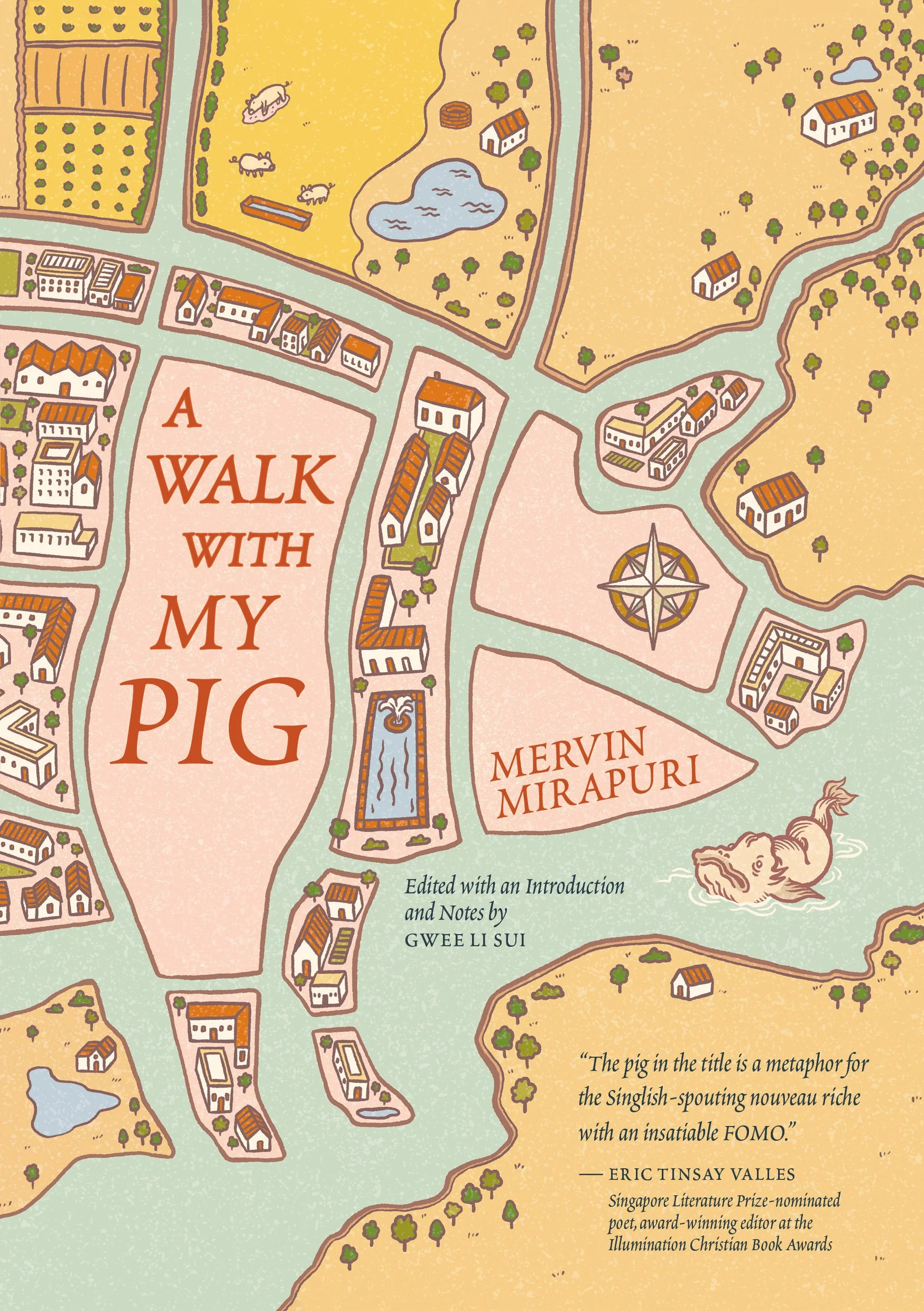

Introduction to Mervin Mirapuri's A WALK WITH MY PIG

By Gwee Li Sui

This introduction is taken from Mervin Mirapuri's A Walk with My Pig, critically edited by Gwee Li Sui and published by Pagesetters Services in late 2023. It is reproduced here with permission.

The production of Mervin Mirapuri’s A Walk with My Pig—or Pig for short—is a work of recovery. This is an emphatically unfinished English-language poem on a scale that is rarely seen attempted in our part of the world. It was not known to exist outside the poet’s circle of loved ones for well over a year after his passing on 6 May 2020. Its drafts were neither collated nor examined completely throughout that grieving period. Pig had been written in obscurity and in a state Mirapuri compared to being in exile. Yet it is unquestionably grand, with both its ambition and style calling for wider attention.

Mirapuri’s last work is this great literary secret we suddenly have, and secrecy makes it an artefact to be treated with care. The challenge is, however, complicated by just how different it reads from all of the poet’s other works—published and unpublished— written in Singapore up to the late 1980s. In view of this, what is needed is not just recovery in the constructive sense of bringing about a final meaning and enabling accurate interpretation. We must also recover to a degree a lost son of Singapore, fathom his artistic journey, and articulate his relevance to both Australian and Singaporean poetry.

The Poet

Mervin Gagandas Mirapuri was born on 6 October 1945 at Lily Maternity Clinic on Serangoon Road in Singapore. His parents Gagandas Lilaram Mirapuri and Teresa Rita Torio had another child two years later, and, on the year Hilda was born, Gagandas left for post-Partition India to assist his family there. He never returned, and Rita took her young ones to live with her mother at Johor Bahru and would later remarry. It required several more decades before the plight of Gagandas was learnt. He and his family had fled Hyderabad Sindh and became refugees for years before settling eventually in Hyderabad India.

In 1954, young Mirapuri started attending Sungei Kadut School—known today as Woodlands Primary School—by crossing the Causeway on foot. Going to Beatty Secondary School next, he became active in sports and the production of plays and the school magazine. He further joined the volunteer youth organisation St John, which he would notably serve right through his adult years in Singapore. Given his humble background, Mirapuri gave private tuition in order to afford furthering his education at Raffles Institution. He also worked as a poster-maker at Mubaruk Bookstore on Serangoon Road and was paid in kind there.

In 1964, Mirapuri entered the then University of Singapore— now the National University of Singapore (NUS)—and majored in economics and political science. His aptitude for higher learning led a professor to invite him to study at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT), but the young man declined. He could not leave his vulnerable family behind, and besides, by that time, he had found love. On 8 October 1966, Mirapuri and Elizabeth Anthonisz married, but this love story is the stuff of another book. The couple brought their first child Dawn into the world the following year.

Graduating with Honours in 1968, Mirapuri was offered a good starting job by the Singapore Police Force. He chose a military career instead, becoming part of the illustrious first graduate batch of officer cadets at the Singapore Armed Forces Training Institute (SAFTI). Mirapuri would rise steadily to the rank of Captain. Those early years also saw him co-found Woodrose Publications with Chandran Nair, Malcolm Koh Ho Ping, and Winston Loong and publish his first collection of poems Eden 22 in 1974. He and Elizabeth had their second child Ann in 1971 and their third Tristan in the year of Eden 22.

By a turn of fate, Mirapuri would leave the army in utter disillusionment in 1978. He worked in the private sector for the next decade until 1988, when he and his family uprooted themselves and moved to Brisbane, Australia. The sudden change and stress from starting afresh in an unfamiliar land and culture proved traumatic. Mirapuri had to put up with impressions some had of Singaporeans being tree-dwellers and Singapore being a place in China. Slow business ventures and encounters with racism and fraud made life tougher still. According to his family, the poet wrote next to nothing in those years.

What became Pig spelt an end to the dry period and can be framed specifically between 2005 and 2011. Earlier in 2000, Mirapuri had found employment as a civil servant again, this time in the Australian Taxation Office. His initial happy return to regular work soon became disheartening and would amount to what he considered to be his lowest point in life. Mirapuri’s family attested to how miserable he felt from his numerous experiences of ageism and other forms of discrimination. In spite of it all, he stayed on until his retirement in 2011, the year when he also stopped writing due to his health issues.

Origins and Journeys

The trigger for Pig came, however, from a somewhat unrelated talking point. On 11 March 2005, Mirapuri’s elder daughter Dawn, then researching with the American University at Cairo, had written an email to her family and friends. She described her recent conference trip to Palestine and what she encountered at the Israeli customs and checkpoints, at the West Bank Wall, in the cities of Ramallah and Jerusalem, and of the suffering Palestinians. Hours later, Mirapuri sent a private reply titled “the dead pig rides again” that revealed how her email had “prompted a few words from me to myself” and attached lines “still in draft mode”.

That titleless poem would become the source text for Pig. Almost all its 185 lines reappear in the eventual six-chapter version, though not always in the same words, sequence, logic, or tone. Beyond an initial edited email printout, we cannot know how many more drafts had existed between these two forms. What we do know is that, months later, on 1 August, Mirapuri emailed another poem to Dawn reaffirming his empathy for how she felt. The 44-line piece also said:

That response to you turned into the writing called

The Walk with My Pig

That Pig now flies

It is certain that, as Mirapuri kept writing, his plan for his project enlarged. He began to see new possibilities for his imagery and obsessively related pigs and birds of prey in prophetic terms to human nature and the age. In an email dated 21 August 2006, he linked an assortment of world news to pigs, “my favourite theme”, and asked excitedly: “Are you guys sure that one of you did not give a copy of my writings to someone out there?” Yet, by the time he conceived of six chapters, the project seemed to have gone in the opposite direction. It became personal, absorbing his immigrant landscape to fill the lingering structure of dominance and oppression.

Pig can indeed be understood to an extent as this expression of a frustrated new Australian. The poem, after all, uses fragments and cross references to present the psyche of one negotiating with a brave, new world that simultaneously excites, confuses, and depresses. Its main character seeks a sure path between inner fulfilment and outward obligations but has only his own resources of family and religion for bearing. What comes up against him is conversely formidable: tides of false promises and disappointments, dangers that corrupt the soul and destroy his dreams, and cautionary tales from all who have fallen by the wayside.

The motif of a harrowing life journey is not unfamiliar in world literature. Arguably the most famous narrative poem with it is Dante Alighieri’s fourteenth-century Divina Commedia (Divine Comedy), which audaciously surveys whole regions of Hell, Purgatory, and Paradise. Its hero—having deserted la verace via, “the true path” (1.1.12)—learns in his long wandering about human nature and the work of divine justice and love. A shorter but strangely grimmer poem from more modern times is Arthur Rimbaud’s Une saison en enfer (1873; A Season in Hell), which deliriously chronicles a fall from joyful youth into world-weariness.

However, the first of all such dark journeys is arguably also the world’s earliest surviving literary work. The second-millennium BCE Mesopotamian Epic of Gilgamesh begins with the rousing adventures of a king of Uruk and his enemy-turned-friend Enkidu. Midway, the gods have Enkidu killed—and suddenly we enter a plot with the grieving hero seeking the secret to eternal life. This is despite being warned:

Gilgamesh, where are you wandering?

The life that you are seeking all around you will not find.

When the gods created mankind

they fixed Death for mankind

and held back Life in their own hands.

(85)

Pig resides firmly within this tradition of a spiritual expulsion from common life. The poem weaves a web of first-person speakers of different genders, ages, and statuses, but its main one is an Abrahamic patriarch, an old traveller of faith whose time, he believes, has come. The man’s arrival at a supposed Promised Land then turns him into a conduit for the voices of his family members, acquaintances, colleagues, and more, all of whom he has to map to grasp his own destiny. The piecing together can bring peace to his turbulent emotions and fraying thoughts and show him the true value of faith and an upright life.

Like Gilgamesh’s exploits with Enkidu, that first journey in Pig is a contrivance, what serves to initiate a radically different second journey. The family man’s coming to Australia brings promise of a good life he warmly receives with the understanding that he ought to change his old ways and mindset. An initial readiness to adapt soon evolves into a pressing moral question about the value of his priorities in “the ahead club” (1.67). Surveying inner feelings, family moments, and the choices others make, he is led to ask: how far into one’s desire to succeed does one crack and ironically self-destruct? To whom is one fundamentally responsible to?

Chapters and Drafts

Mirapuri’s poem opens with an array of estimations, visions, and forewarnings, a mix of anticipation and hesitancy. At 1,044 lines, its first chapter is longer than the next three chapters put together and constitutes over a third of its length. The weight here is meant to set up a confused confluence of worldly and moral well-being, with religious imagery doubling, in fact, as a secular one throughout. Chapter Two goes on to build up a buoyant myth of immigrant destiny. We read the success story of an uncouth, Singlish-speaking pig farmer who, with un-self-conscious humour, reaffirms this glittering trajectory of sheer hard work and tenacity.

Chapter Three—the shortest segment at just 107 lines—then takes us into a pivotal moment that lays out the high stakes. The game of life is promised to be “a festival of eagles” (3.107) where any participant can emerge as a winner. Yet, what follows in the next two chapters subverts it all, detailing first the compromises individuals make on a regular basis, the global scale of such shortcomings, and the related devastation to each soul. Then comes the mechanism of capitalist evil simplified as always a relationship of two, between an exploiter and a disenfranchised, the pimp or client and the sex worker, the rich and the poor, and so on.

The whole of Chapter Six rises out of an enlightened place that brings all these experiences into focus. It launches with no less than the voice of God booming as lengthily as it did in a Biblical response to the suffering, questioning Job. Pig’s old fool comes to accept the world’s fallenness and his own mistakes and forgives himself for not understanding sooner:

Be still and know that I am

Man was I stupid or what

I didn’t have to eat dead pigs at all

(6.423-425)

He rediscovers the eternity of the Lord’s day, that creative beginning of life where abounding joy forever awaits.

From the source text of 11 March 2005, we know that Mirapuri had always been clear about where his project needed to go. Pig starts and ends in roughly the same place as that early, much shorter, tighter poem—although everything in the middle tells a different story. We know that Mirapuri eventually worked by keeping his latest revision in a white binder; yet his last compilation, as with a previous compilation, shows chapters with different or no page numbers at all. What this means is that the parts remain at different stages of completion, making clarity across them uneven and inner connections at least serviceable.

Only Chapters One, Four, Five, and Six carry material found in the source text. Chapters Two and Three seem to arrive from a different place, and we cannot tell when either was written or whether they were meant originally to play a role in Pig. These two chapters, notably the shortest, are also the stablest, changing little in their available drafts. By comparison, a late draft of Chapter Five still shows heavy revision, with markings and scribbles that manifest fluidity in wording and rethinking. It may be useful to point out at this stage though that no chapter is, in fact, ever numbered in the drafts or a list of contents.

At the time of my introduction’s writing, two complete sets of drafts exist, securing for every chapter at least two versions. Both Chapters One and Three have a total of three drafts each while Chapter Four has the most, with four. The set drafts and the loose drafts show an interesting physical difference in that the former alone possesses binder holes. We can draw from this that the latter might not have belonged in the last stages of editing. As such, we have no reason to believe that no other drafts exist whether between what is bound and what is loose or, for that matter, between the source text and the six-chapter form.

Also, while the poem’s last recorded title is A Walk with My Dead Pig, Mirapuri had used A Walk with My Pig and just Pig elsewhere too. All three titles seem valid, but a dual presence appears to be preferred later. In fact, Chapter One establishes the main human character as this dead pig while Chapter Four resurrects him as a “Last Pig Standing” who witnesses human degradation. The living-dead, man-animal duality may be clearest in Chapter Two, where the titular “Pig at the Markets” is both a real dead pig and its speaking owner. This walk with oneself, we remind ourselves, echoes Mirapuri’s point about the poem being first “a few words from me to myself”.

Pigs and Eagles

All of the work’s worldly creatures, be they pigs or eagles, are said to mutter whereas what ultimately redeems is not the mouth but the eye. Even a pig’s eye can survey and create wisdom—hence the redemptive Chapter Six’s title “Eye of the Pig”. Mirapuri’s twin devices of pigs and eagles are references not so much to immutable types of human nature as to socio-cultural stances. His pigs suggest an unrestrained form of crass, servile existence people choose simply to “Come Sleep Walk” (2.48). Eagles, on the other hand, are expert opportunists, achievers psyched to outperform others by sensing and seizing every occasion to thrive.

In both the pigs that eat and get eaten and the eagles that prey on the vulnerable, the common ground is food. Eating plays an unusual, key role in a poem where the settings range from a party feast and a visit to McDonald’s to the scavenging of rats. The point of maintaining a healthy diet is itself extended into a metaphor for how or whether we even care about our spiritual well-being. Thus, abject poverty is described in terms of contaminated food we give to the poor and children “drinking water with animal poo mix” (1.244); perversion is brought to bear on our minds via paid oral intercourse.

The true north of Pig is, without doubt, Isaiah 40.31. This Biblical verse describes how God sought to comfort sixth-century BCE Jews who were crushed and exiled in Neo-Assyrian Mesopotamia. He gave them a promise of renewed strength to fly as well as eagles if only they would keep trusting Him. Pig’s chief reference is itself the Book of Isaiah, from which four chapters derive their epigraphs in the King James Version (KJV). Its centrality sets exile as the work’s emotional context, and so, like God’s uprooted people, its main persona is caught between divine calling and the lure of Babylon.

This dilemma of action, with its risks and consequences, permeates the whole poem. Happy children in a good family are contrasted with others whose innocence has been defiled by coercion into illegal sex work. The childhood that individuals cannot choose plays an enigmatic large part in the adults they will become. Young souls are accordingly symbolised by pockets: as big as these are to be able to hold stars, they can still be stolen from or torn with ease. Children can be robbed of their future or damaged irreparably, and this truth extends to all of us as God’s offspring too. “We belong,” we read at one point: “We are all children” (1.638-639).

Therefore, the call to trust God comes coupled here with a plea to be trustworthy ourselves, to be as God is to us. To go the other way, those who lack spiritual interest or make themselves their sole masters become unmoored and accountable to no one. They lose their moral compasses. Pig begins with a positive vision of this self-made person as forward-looking, regenerative, and indomitable. We read at first of a desire to acquire “new parts” (1.84), an endeavour that worsens into a Frankensteinian possibility of never becoming quite whole. What if being only human must involve our refusal to think and act by our bestial appetites?

The poem’s closing moments confront the challenge by fixing on its own recurring motif of free tickets. According to Mirapuri’s family, these curios actually possess a biographical context. The poet, at one stage in time, kept small, blank slips of paper folded in his pockets to give out to friends. It was a puzzling ritual charged with private significance, and, when asked, he would call the slips “tickets to Heaven” since “you go to Heaven by faith and not by sight”. Mirapuri’s wife Elizabeth remembers how, at one Christmas gathering, a guest had vehemently refused to accept a slip, making the time rather uncomfortable.

From the fractured world of Pig that collapses from too much frustrated desire, we can now venture into some understanding. Mirapuri’s tickets represent how life’s true gift—like life itself as gift —is radically free. Its blessings cannot be bought, sold, or acquired via status, talent, industry, good luck, or some less respectable means. As it can only be received, while generosity is real, nothing is owed since the gift arrives without charge:

Be happy anyway

The gift was free in the first place and in the second place

and the third place

No one paid for a ticket to have these so what if one gift

seems a broken promise

an irrelevant gift

(6.466-671)

To bewail our lot or the outcomes of our choices is to assume that we ever deserve anything. Mirapuri realises that what freedom we think can fulfil us has always come chained to the things we need to be free from. The right posture towards life is thus to appreciate being empty at our core. Pig ends by exalting the present, this wealth we foolishly keep squandering away in our big dreams of tomorrow. The acclamation also hauntingly brings the poet’s own writing journey to an end. It is a closure we may perhaps see as enabled by an awareness that even the gift of poetry should be found expendable at the gates of wisdom.

First published in A Walk With My Pig, by Mervin Mirapuri (Pagesetters Services, 2023)

Works Mentioned

Dante, Alighieri. The Divine Comedy of Dante Alighieri. 3 vols. Trans. and intro. Allen Mandelbaum. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1980-1982.

The Epic of Gilgamesh. Trans. and intro. Maureen Gallery Kovacs. Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1989.

The Holy Bible: King James Version. 1611. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1984.

Rimbaud, Arthur. Collected Poems. Trans. and intro. Oliver Bernard. London: Penguin Books, 1962.

Gwee Li Sui is a poet, a graphic artist, and a literary critic. His works include seven poetry books, the latest being This Floating World; graphic novels such as Myth of the Stone; non-fiction titles such as FEAR NO POETRY! and Spiaking Singlish; and Singlish translations of works by Antoine de Saint Exupéry, Beatrix Potter, the Brothers Grimm, and A. A. Milne. He has also edited several acclaimed literary anthologies.

If you’ve enjoyed reading this article, please consider making a donation. Your donation goes towards paying our contributors and a modest stipend to our editors. Singapore Unbound is powered by volunteers, and we depend on individual supporters. To maintain our independence, we do not seek or accept direct funding from any government.

In this essay, one of three winners of the 2023 Singapore Unbound Awards for the Best Undergraduate Critical Essays on Singapore and Other Literatures, Gan Chong Jing argues that Singaporean playwright Kuo Pao Kun creates a uniquely fluid form of allegorical theatre by infusing experimental, non-realist English language theatre with Chinese Xiangsheng performance techniques.