Special Focus - The Leeds Poems of Arthur Yap (Part 3)

Singapore Poetry’s “Special Focus” series highlights an important aspect of the work of an established Singapore author. By making available a substantial selection of work, SP hopes to encourage both readerly and critical engagement with the author. We begin to see connections, reiterations, and reformulations that are missed in reading just one work. The inaugural series looked at the extraordinary gardening poems of Leong Liew Geok. The second series brought you the searing brand of truth-telling in the writings of Justin Chin.

This third series focuses on the enigmatic Leeds poems of Arthur Yap (1943 - 2006). Born and educated in Singapore, Yap went to the University of Leeds, UK, in 1974, at the age of thirty-one, to study for a Masters Degree in Linguistics and English Language Teaching. Inspired by his experience living in that city, his Leeds poems are arguably pivotal in his poetic development. The series presents the poems in two parts, followed in Part Three by the first-time publication of an illuminating essay by British critic and Leeds resident, Andrew Howdle, on Yap's relationship to the city of Leeds. Read Part 1 and Part 2.

The Leeds Poems of Arthur Yap

By Andrew Howdle

Arthur Yap was born on January 11th, 1943. Popularly, he is described as being an introspective student (at St Andrew’s School, Singapore) who developed into an intensely private thinker; a poet who wrote hermetically sealed poems that avoid biography; a painter who composed abstract paintings that remove themselves from life. It is thought that his work, poetic and visual, did not choose to investigate social issues beyond reflecting society “and its values”, or social “commonplacities” (1). The portraits created of him, in works of criticism, rarely stray from this view. When he does become flesh and blood, he is remembered as a sketch rather than a human being: a man whose physical appearance was as “pared down” as his verse, came one verdict written shortly after his death from nasopharyngeal cancer in 2006. (2).

In the current climate of Yap studies, it seems almost transgressive to disagree and suggest (against the revered tenets of theory) that there are human hands behind the works, hands that leave discernible marks of identity. I wish to argue that there are such marks in Yap’s poetry. This essay will walk closely with the reader through his poetry and reflect on the particular connections he made between art and the urban landscape of Leeds.

In a 1982 interview with Gillian Pow-Chong, Yap made a telling statement about his work: “I do not luxuriate in what I have completed… In fact, I can feel very detached from my completed works” (3). The detachment fits the usual portrait of Arthur Yap. The much more interesting word, however, is “luxuriate”. Though Yap goes on to talk about art becoming a luxury in modern Singapore, his meaning here is drawn from much older Anglican resonances: he is denying himself self-indulgence, from seeking a sinful pleasure in his writing. Far from being the familiar bleak writer playing with words on the page or shapes on canvas, he comes across here as a sensual individual who places boundaries.

In 1974, at the age of thirty-one, having achieved a British Council scholarship, Arthur Yap left Singapore for Leeds, West Yorkshire, England. The purpose of this excursion was to study for a Masters Degree in Linguistics and English Language Teaching. This Dantesque move “midway in the journey of our life” was a pivotal point. By 1974, he was an established painter and poet. He had exhibited nationally and internationally and had published Only Lines in 1971. Consequently, he came to Leeds, as a young artist and poet with a reputation. His new research was to be a step away from his degree in English Literature towards a focus on English Language and Education and on teaching at a higher level. Leeds also offered something beyond a career move, however, as it presented a less restrictive society and a different environment in which to develop, paint and write.

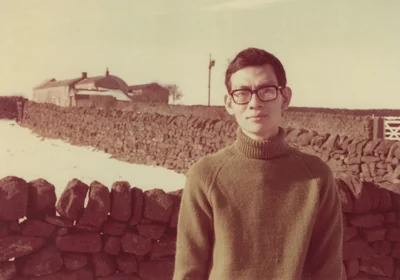

Photographs of Yap, during his time in England, present a face that engages the camera. In one, he stands against a Yorkshire landscape of snow and dry-stone walling and stares through his spectacles with a mild and benevolent gaze. With his short hair, sharp cheek-bones and plain rolled neck jumper, a typical fashion buy from any Leeds department store in the 1970s, he appears as an unassuming man younger than his years. There is modesty and assurance and both of these qualities exist in his Leeds poems.

The forty-five poems in Commonplace are accompanied by twelve black and white abstract acrylics on canvas. The paintings included in Commonplace serve three purposes. For marketing reasons, they place Yap in a rare line of poet-artists, William Blake, William Morris, Dante Gabriel Rossetti, D.H. Lawrence, David Jones, and, closer to Yap in terms of time and style, Charles Tomlinson. They implicitly draw a parallel between Yap and the poet-painters in Chinese history. The pictorial element intimates a visionary quality, a sense of tranquillity, inner confinement and insight. The twelve abstracts also suggest that the poems be read as thematic variations and as optical arrangements. The recurring window motif connects symbolically to vision and to the real world: windows dominate the immediate landscape in which Yap was a new resident. Looking away from the numinous windows of Leeds University, the eye is absorbed by a valley of glass frames, Victorian facades with repetitive glass forms, terraced back-to back houses with their rhythm of glass and brick and ornate ecclesiastical windows. Finally, the art-works zone the poems into sections: 10/4/14/4/14/4/7. The numeral 4 sounds like “death” in Chinese whereas the numeral 14 sounds like “will die.” A commonplace fear in Singaporean culture, the ominous repetition is inserted as a piece of dark humour. (It should be noted that Commonplace opens and closes with car accidents: “black & white” and “group dynamics ii”). Elegiac images flash throughout Commonplace. The Leeds poems, which are the focus of this essay, are contained in the third section.

Because of the emphasis on Yap’s hermetic and solipsistic tendencies, criticism tends to be rather vague on simple connections between Yap’s poetry and reality. So, perhaps it is necessary to pause for a moment and establish some basic facts. It is correct to say that Yap came to live in England. It is incorrect, however, to say with some critics that those poems placed outside Singapore are set in England. One poem, “caernavon”, a misprint for Caernarvon, is set in Wales. Also, Ee Tiang Hong, in his Foreword to Commonplace, wrongly identifies Yap’s itinerary as “Leeds, Woodhouse Moor” (4). There is an assumption that Woodhouse Moor is a location separate from Leeds, maybe a place like the Brontës’ famous Haworth Moor. In fact, Woodhouse Moor is within Leeds and it is not a wild place of any description. Quite the opposite, it is a man-made area of cultivated parkland.

Yap opens his life in Leeds with a humorous jibe at the English University system. His poem, “prof”, commences as a tribute:

when he passed the quadrangle, there might

have been in him the desire to be a statue;

A reader is given a glimpse of a melancholic academic who, deep in thought, wants to “forget [himself] to marble” (5). The mood elevates towards the universal until a return occurs and the weather becomes the “gloomy” mood inside the University. At this point, the professor assumes a darker role:

in the gloomy theatre, an immense face

composed of many insights,

prefacing a lecture with ‘if & only if”.

The poem subsides into satire and Yap’s free-verse sonnet captures the pompous ambition of academia, with its gaze more on status than clarity of thought. In this world, a professor is still entitled "to recycle/bullshit as bullion". The modern meaning of “recycle” is used with full irony as a student of linguistics directs his wit towards his superior. Though we use this word freely now, in the general sense of turning waste into something useful, that meaning did not emerge until the late 1960s. (Indeed, it is not listed in the 1971 OED). The professor’s methods are current, like his ability to alchemize waste into gold, as the caustic pun states.

The next poem located within Leeds is “north hill road, leeds.” North Hill Road is a small residential side-road leading off from Headingley Lane, one of the main routes into the city centre. It is close to Woodhouse Moor and this area would have been the home for many students in 1974-75 as it contains two major halls of residence, Devonshire Hall and North Hill Court. The poem is a kind of nocturne: usually, a musical nocturne would be performed around 11pm.

the few 11pm lights are busy exchanging signals

with, above, the glinty stars :

little poke-holes on a large black tarpaulin

pegged down by nerveless wintry branches.

Yap’s precise punctuation and syntax simulate a moment of perception. The residential hall lights are communicating, but what and to whom? The expected clause, with the “glinty” stars above, is fragmented. A reader’s eye takes in the window lights, followed by the nebulous darkness above, and finally the stars. A disconnected image creates a sense of dislocation. The unusual “glinty” suggests that the stars are too bright, which is the case in winter when stars in the Northern Hemisphere increase in intensity. Are they too showy and public, perhaps, for the modest eyes of Yap? The stars speak a punched-hole computer code that is distant from his situation. By viewing night as a “black tarpaulin”, Yap quietly suggests that this night is a voyage and he is a wanderer tented from the elements. The word that strikes strongly in the opening section is “nerveless”. Impassive and insensate, the trees are part of a scene that benumbs. The exterior world described by Yap is viewed from a distance and preserves the distance, though it touches the writer’s state of mind. The interior world is similarly nerveless:

i’m already in my room

wallpapered with a few numbed thoughts;

Mind and room merge as the wallpaper of the room covers the writer. By picking up contemporary references such as wallpaper music (in city shops) and wallpaper talk (on radio) where wallpaper indicates a background without meaning, anathema to a visual abstract artist, Yap describes a loss of sensation.

The closing three lines of the poem take the reader and writer back to the window, back to a liminal place between inside and outside and a symbolic place of vision. Looking outward, Yap observes an imaginary scene from earlier in the evening when he walked home:

this image i seem to see continually

as if it demands a profile

now that i’m no longer there.

By forcing himself to sense once more, he sees a profile of himself, a form that is recognised by others, which insists on existing. The poem “north hill road, leeds” is a restrained yet nonetheless moving poem about isolation and loss of identity.

“north hill road” possesses a filmic quality, and film is returned to again in “new year 75, leeds”. Events centre on the Western New Year when snow fell repeatedly in Northern England. In analysing this poem, Boey Kim Cheng has argued that Yap exhibits “existential disconnection” and presents a characteristically detached and “cursory tour of the Leeds cityscape; places are named without affection or attachment” (6). It is true that “new year 75, leeds” carries on the austere mood of “north hill road, leeds”. But in this poem, Yap provides a detailed and very personal view of Leeds and its cultural and geographical climate.

The opening location for this poem is one of the many Chinese restaurants that existed in Leeds city centre. Unfamiliar with the Western New Year in the West, Yap and a friend, Vu, find themselves in a “new year, as if by error”. By the mid-1970s, eating Chinese food, in and out of the family home, was quite fashionable in northern England, and the presence of so many English diners takes Yap by surprise. As he notes, “my vietnamese friend & i, [are]/the only asians”. The scene within the restaurant is served up, by Yap, with condensed wit:

the waiters served graces & teeming dishes

and the good laodiceans smiled warmly and scrutably…

our cheer our tea, our leedsfraumilch 75,

kitchen-fresh vintage.

Punning on Laotian/Laodicean, the uncommitted seventh church in the biblical book of Revelation, the Chinese waiters are recognised as lukewarm and perfunctory in their duties; unlike the two Asians who have gone from freezing cold to hot. The idiomatic “our cheer our tea” suggests a popular claim that sharing a chat and a cup of tea drives gloom away and can put the world to rights. There is also an echo of a very English belief that tea is better than wine: Boswell wrote in the 18th century, the birth of English tea drinking, that grapes should yield to tea; and Cowper also recommended tea because it cheered without causing drunkenness. With this in mind, the clever pun “leedsfraumilch 75” refers to the milky tea being drunk by Yap and Vu: it is a “kitchen-fresh vintage”, freshly brewed and better than wine.

Previous to the meal of noodles, Yap and Vu had been to The Plaza cinema, in New Briggate, a place well known for screening European porn films:

The Plaza cinema © Leeds City Libraries, 1970

…x-rated films

are lined up each week, cheek by jowl.

The euphemistic art films, are viewed drolly as “lined up”, like movie-goers, in a queue.

After the restaurant, they return to their homes via Woodhouse Lane and head towards the University branch of Austicks bookshop. (It now belongs to Blackwell). The place is identified with affection as a “frequent haven”. Out of all the words that could have been selected to mean refuge, “haven” is one of the most intimate: as a port for ships the word echoes the tarpaulin/voyage imagery in “north hill road, leeds” and it carries biblical resonances that suggest safety and rest for the soul. Books had been a valuable part of Yap’s formative years. He had read all of the novels of D.H. Lawrence whilst still a teenager. Consequently, Austicks counts as an emblematic place for Yap as he journeys home.

Former Austicks Bookshop. Photo: Andrew Howdle

Some one hundred metres from Austicks is the imposing Parkinson Building that stands as the major symbolic edifice of Leeds University. But Yap does not acknowledge it as this. Instead, he recognises it as the entrance to the Brotherton Arts Library. As with Austicks, this journey out of Leeds connects to his own private world of literature.

Parkinson Building, Leeds University. Photo: Andrew Howdle

A further five hundred metres brings the reader and Yap to the beginning of Woodhouse Moor: “all somewhat remotely outlined in a thin swirling snow”. Vu’s “hostel” is now close (just off from Hyde Park Corner): most probably, Devonshire Hall. It is exactly “half a mile more” (eight hundred metres), as Yap accurately records, from here to the top of North Hill Road and his residence.

The poem closes by returning to The Plaza. As in porn films of the 70s, when sex acts were blurred out or snowy, everything is “soft-focal”. Time unwinds backwards: snow, the Moor, noodles, the restaurant, the cinema, sexual close-ups; night becomes blurred as if it is seen without spectacles (connoting Yap’s own myopia?). Then time winds violently forward…as it might in a film:

snow, steaming noodles, celluloid close-ups,

& night’s myopia. next day, next year.

In “new year 75, leeds”, Yap is autobiographical and very specific about places and events. The poem also provides a touching vignette of Vu. He is kept in mind throughout the poem. Firstly, he is identified as a “friend” (l.2); then, recalled as still freezing in the warm restaurant, so much so that he defies polite convention and does not take off his “cossack-like cap” (l.8). Together, they sit “cheek by jowl” (l.13) in the cinema, crammed in as part of an audience, also close together. Vu’s intellectual comment that the porn film had “no psychological/reality” (ll.13-14) is both a rejection of the film and a shared in-joke about their linguistic interests outside sex films: Sapir and Chomsky. There is no fond farewell as they part, but a placement in mind of where Vu lives, where Yap lives, and the distance between them (l.9). If a reader looks at where descriptions occur of Vu, then s/he is struck with the careful distribution of details, every 5-6 lines. The relationship to Vu binds the poem together and a geographical reality is inseparable from a human one.

The fifth poem in Commonplace, “evening”, has no stated locality. It commences, however, in a striking manner that identifies its location within Leeds. The poem is worth a close reading, as it is possible to see a scene come alive and glimpse the flow of images within Yap’s mind, a movement between landscape and abstraction. The poem begins, “bilabial at the edge of earth & water”. Initially, a reader is puzzled by the abstraction. The term “bilabial” locks the mind. Who is bilabial? What is bilabial? The mind has a picture of a place where two elements meet, so a riverbank. The poem suggests a moment of transition. And the simplicity of natural forms suggests a Chinese painting. The bilabial word that is often used to describe a small river in English poetry is “babbling”, as in Tennyson’s“The Brook”, in which waters babble bilabially with relish (7):

I bubble into eddying bays,

I babble on the pebbles.

I chatter, chatter, as I flow

To join the brimming river,

For men may come and men may go,

But I go on for ever.

In contrast, Yap’s abstract “bilabial” becomes a state-of-mind that relates to the act of speaking and listening to sounds. Mouth and ears correspond in Chinese medicine to the elements of earth and water. The “bilabial” refers to the river’s speech. But this is a characteristic Yap-like stream: it is without the “I” and egotistical voice of Tennyson’s brook as it muses on man’s mortality. The next line introduces a firm image of solidity. There is a river and a pathway across, made from stones. There is a poem built from bilabials:

bilabial at the edge of earth & water

stepping-stones like giant molars

grow old, grow dead.

Behind all of this, there is a real location not far from North Hill Road and the previous settings for Yap’s poems. The land behind North Hill Road leads directly onto Woodhouse Ridge and then slopes into Meanwood Valley. This area of protected greenbelt contains the well-known Meanwood Trail that follows the course of a winding beck (Northern dialect for brook). There is one location along the Meanwood Valley where the brook is crossed by stepping stones made from large millstones. The Latin for millstone is mola and this is the root of molaris dens, the scientific name for molar teeth. Like millstones made for macerating grain, molars are teeth designed for the grinding of food. Yap’s specific image is rooted in this location. More than forty years has passed since Yap’s poem was written, but some of the stones still exist.

Meanwood Trail, in Meanwood Valley. Photo: Andrew Howdle

Yap’s “evening” is a kind of pastoral elegy in which East and West coincide. It is a sojourn in early summer under an “aestival sun”. The archaic and latinate reference to summer re-imagines Virgil’s Georgics and the origins of English pastoral poetry. If you follow the beck in early May, winding under low-bending trees and past small areas of farmland that follow the rounds of agriculture, one of the most noticeable sights is the leaning daffodils and their dying, tissue petals. (The May dating of this poem can be classed as summer because British Summer Time has just begun). This is exactly the scene in “evening”:

daffodils have bloomed, dead

now, keening in a heap.

The line-turn after “dead” momentarily holds death still and “keening” beautifully captures the lamenting, stooped heads of daffodils. At this point, the poem could lapse into sentimentality, but Yap quickly balances the lyrical tone with haiku-inspired perceptions:

sudden flare of an evening,

supposition of night blown by a slight breeze

right here, right now.

There is an Imagistic brevity at the close of the poem, a quality that arrests time tranquilly. Unlike Tennyson’s brook that labours its point about mankind’s mortality and impending death, Yap’s synthesised Anglo-Asian poem remains in the present, “right here, right now.” Zen answers churchy moralising. The writing in “evening” is concentrated and words are chosen to create intelligent ripples in the reader’s mind. A similar moment occurs in the simpler poem, “ a scene”, where a tree “bilocates night and day”. On one side, day departs. On the other side, night arrives. In the middle, the tree is simply in the present, yet sharing a double awareness of past and future.

The remaining Leeds poems in Commonplace include “accelerando”, “a patch of yellow cabbage flowers”, “lunch hour concert, leeds town hall”, “a summer funfair”, “commonplace” and “gaudy turnout”. Woodhouse Moor provides the setting for “a patch of yellow cabbage flowers” and gives an autumnal view of the vegetable allotments that were built there after World War II to encourage self-sufficiency.

Vegetable allotments in Woodhouse Moor. Photo: Andrew Howdle

The Moor is also the likely setting for “a summer fair”. Yap mentions that the fair failed to lure undergraduates from their exam revision, so the location must be close to the University. Lunch hour concerts at Leeds Town Hall are a tradition that goes back to 1940 when communal music events were designed to uplift the city during World War II. As night times were too dangerous for venturing out, events during daylight became the norm. “lunch hour concert, leeds town hall” is a reflection on a piano recital on a typical rainy day in Leeds. Rain permeates the poem until outside and inside, life and art, merge into one.

The final poems set in Leeds offer antithetical views of day and night. (They develop the day/night symbol of “a scene”). The poem “commonplace” takes the reader through a day in Leeds. Events come and go in a continual return. A disjointed opening, miming the disconnectedness of waking, leads into the moderately slow hours of the afternoon and then the energy of rush hour:

… this morning’s streets

are already rattling cars & buses back

into younger & less immediate parts of the city.

The style of writing resembles Futurist collage poetry, but turns that school’s collective fascination with energy and electricity and modern light into something ordinary. The quotidian prevails in urban living.

when night comes, it will come in neonlights.

when night comes, will it come in darkness

or will it bring its own light to a well-scrubbed day?

But slight changes, as in the dialectical syntax of the poem – it will come/will it come – can make routine life yield distinctive and affirmative perceptions. Life in “Commonplace” is a “well-scrubbed” day, a clean and presentable twelve hours. The phrase “well-scrubbed” is turned inside out in the final poem. To scrub up well means to be dressed cleanly or turned out well. And “gaudy turnout” turns the reader towards a darker and private aspect of Leeds.

Cyril Wong has written illuminatingly in his essay, “except for a word”, on this poem’s implicit homoeroticism (and his view is certainly correct). He is one of the few critics to acknowledge the “kindness” in Yap, as a person, and the “quiet but generous” nature of his work (8). And yes, that is true of Yap’s Leeds poems. They can be faulted as hermetic and solipsistic, difficult and cut-off, or they can be read considerately as spaces that open themselves for meditation. And they do open up, if a reader is prepared to walk or cruise with them.

Behind “gaudy”, in “gaudy turnout” a reader can hear, as so often with Yap’s poetry, a spectral world of lexical shades: gaudy, joyful, gay; showy, too bright, outrageously gay. The word gay is the terminus of all word trails. In connecting this poem to Leeds it is history rather than geography that matters. A single question is crucial: if this is a poem about homoerotic desire, what context allowed it to be written?

In 1959, under the editorship of Tony Harrison, the weekly University poetry magazine, Poetry and Audience, published James Kirkup’s "Gay Boys". Even though the poem was set in Japan and well distanced from the United Kingdom, there was a backlash that accused the poet and journal of encouraging vice. John Silkin, as the new Gregory Fellow for Poetry, made a spirited defence. There is a connection between gay equality, freedom of speech and Leeds that stretches back over a decade before Commonplace. The issues defended by academia had been defended in the streets of Leeds for even longer. The Hope and Anchor Pub, renamed The New Penny in 1975, was the first openly gay venue outside London and is one of the oldest gay venues in the United Kingdom: it dates back to 1953. In the 1970s, the Leeds gay scene was characterised by two distinct groups, the “towns” and the “gowns”, the local residents and those from the University. These two groups mixed freely but were distinguished by their attire. Leeds was renowned for its cloth and tailoring industry in the 1970s, so the fixed residents wore suits that allowed them to blend in with the city. The transient students wore garish patterned shirts and were much more noticeable. Yap’s poem “gaudy turnout” glances at both groups: the well-turned-out “suits” and the gaudy shirted “gowns”.

From a reader’s point-of-view, “gaudy turnout” is a complex poem. Yap does not present it as more significant than the other poems. It is no more autobiographical than “north hill road, leeds” or “new year 75, leeds”. Over-statement must be avoided. And yet, here, as the closing view of Leeds, is a poem about homoerotic desire— a dangerous poem given the times in which it was written and the places it was most likely to be read. (Though England had decriminalised homosexuality by 1977, the year of publication of Commonplace, it did so to regulate it, not to support it. And Singapore maintains its anti-homosexuality laws even today). The 14 lines of “gaudy turnout” imply a Shakespearean love sonnet: 3 zoned sections plus a couplet. In Yap’s poem, the concluding couplet is a second, introspective voice, making the poem into a self-reflective dialogue.

The phrase “if i were you” occurs in the poem twice, but with a different inflection each time. On the first occasion, it starts the poem and carries a sense of longing. The tone is solicitous and connects with images that locate proverbial gay scenes, places that take night as cover yet need light to advertise presence: “a lamp post or lit shop-front”. The subjunctive mood introduces a longing for “the quick of your heart”. Through the personification of night, sexual isolation is depicted with aching emotion:

how many, who won’t be there. sensitive is the ear

of night & hears a loneliness for miles.

This is the one line within the poem that uses iambic pentameter and the familiar sonnet metre tunes the reader’s sensitive ear into the world of the love sonnet.

As well as an ear for isolation, Yap’s poetry has an ear for salaciousness and bawdy innuendo and these are used in this poem to express hesitancy towards the gay scene; and by implication, a secondary identity.

will there be dancing cheek-to-cheek? will someone

be recounting minutely his peculiar operation?

& is someone keeping score? will you

shut the door? why do you groan & groan?

Will there be “dancing cheek to cheek?”, which was the tag line for the musical Top Hat, suggesting romance. It also carries the innuendo, backside. The question asked about the latest “peculiar operation” puns on “peculiar” as private /sexual parts. Will someone be “keeping score?” asks about the rates of intercourse (This would be a recent development of the metaphor in 1975.). And “will you/ shut the door?” refers to the most popular catchphrase of the camp variety star and television comedian, Larry Grayson, whose “Shut that door” played on gay sexuality and its history. Shutting the door was important because the Sexual Offences Act (1967) made homosexuality legal in private and if private meant not in the view/presence of a third person, then shutting the door was necessary. By 1974-75, Grayson’s “Shut that door”, invariably delivered with limp wrist on hip, was a byword for homosexual. The flow of questions in this third stanza of “gaudy turnout” also mimics the rhetorical style of the Shakespearean sonnet, as do the many wills that allude to Shakespeare’s pun for penis in Sonnets CXXXV and CXXXVI.

The first section of the poem can be read as Yap imagining what it would be like to step out of himself and enter a world of uninhibited longing, the space of the “town” male. The repetition of “if I were you” at the poem’s close (its couplet) sounds very different from the opening:

if I were you, a gaudy boy afflicted with joy :

sensitive is the eye of day and & sees a leer for miles.

Now, the “if” is colloquial. It sounds like the statement an English Northerner would make when giving advice, a hint emphasised with a wag of the finger. “Oh, if I were you, I wouldn’t do that.” The tone is matter-of-fact and suggests that the speaker is stepping back inside himself, into the “gaudy boy”, an academic gay, and recognising that he is “afflicted”. The term “afflicted” records the commonplace view of gayness as a disease— even though the Wolfenden report repudiated this, in 1957.

Also worth noting is a very precise literary allusion for Yap’s use of “gaudy” in this poem. This once more sets the word within a gay context. The most visible images of gayness in literature, in the 1970s, were in the poetry of Thom Gunn. And the volume to look at would be My Sad Captains (1961). As a devoted Jacobean, Gunn borrowed his title from Shakespeare: “Come,/Let’s have one other gaudy night: call to me/All my sad captains”. (9) Cleopatra’s joyful night for her sad military followers transforms, in Gunn’s poems, into ga(ud)y/extravagant nights for sex. As Gunn puts the matter: “A single night is plenty for/Every magnanimous device”. (10) The final couplet of “gaudy turnout” concludes a highly personal poem with a sense of unease. If night opens longing, so day opens danger because a desiring eye is too easily seen. The final view of Yap’s life in Leeds is one of self-questioning and a concern for how official and unofficial selves fit together. As well as a poem about unrequited desire, “gaudy turnout” is also a warning about collective identity. The danger, by day, is the “leer”, derived from ler, the cheek, the sly sexual cheekiness of the gay scene.

Throughout the Leeds poems in Commonplace, Yap’s poetry investigates the connections between outer and inner geographies, landscapes and mindscapes, and the relationship between the world and the book. Yap’s writing in the Leeds poems is far from hasty and superficial; the hands that moved across the poetic canvasses have felt deeply and touched sensitively.

Notes:

(1)The Straits Times, Arthur Yap to Lena Bandera, p.1, November 4th, 1979.

(2) The Straits Times, Janadas Devan, p.24, June 25th, 2006.

(3) The Straits Times, Gillian Pow-Chong, p.2, May 30th, 1982.

(4) Commonplace, p.x, Heinemann, Singapore, 1977.

(5) John Milton, "Il Penseroso", l.42, p.141, Complete Shorter Poems, Longman, 1978.

(6) Common Lines and City Spaces, Boey Kim Cheng, “the same tableau, intrinsically still’, p.60, ISEAS, Singapore, 2014.

(7) Alfred Lord Tennyson, “The Brook, An Idyll”, ll.15-16, pp 344, The Complete Poetical Works, Boston. 1872.

(8) Common Lines and City Spaces, “except for a word”, Cyril Wong, p.133, ISEAS, Singapore, 2014.

(9) Anthony and Cleopatra, III xiii, lines 182-4, pp.142-3, Arden Shakespeare, London, 1981.

(10) Thom Gunn, “Modes of Pleasure” (2), Collected Poems, p.102, Faber, London, 1993.

Thank you to Jee Leong Koh for his valuable insights into Singapore and to Professor Emeritus Stevie Davies for being my honest and trusted reader.

Andrew Howdle is a retired educator. After studying English Language and Literature at the University of Manchester and undertaking research into Ezra Pound at the University of York, he moved into education. He worked for thirty years as an English and Arts co-ordinator and as an Educational Theatre consultant in Leeds, England. He now devotes his time to painting, poetry and literary criticism when the wind is in the right direction.