The Impossible Cartoonist

From the archives (December 8, 2016):

Pathways of Reading: The Art of Charlie Chan Hock Chye

By Y.S. Pek

In this blog-post, I wish to make three observations on Sonny Liew’s widely-discussed graphic novel, rather than expound a single thesis. I begin with the idea that The Art of Charlie Chan Hock Chye, in content and in form, is shaped by a strong pedagogical impulse. By no means does an engagement with teaching imply that this work is staid or didactic, for it is also an act of radical reimagining. It is very much to my second point that Charlie, the novel’s protagonist, is an historically impossible figure. Finally, I go on to show how the graphic novel puts in place a narrative structure that is schematizing and clarifying.

If pedagogy can be conceived in its most basic form as the presentation of information, Charlie Chan is a pedagogical text, to borrow Liew’s own description of his work. “Visual information” was the specific term that he used when we spoke this summer. In fact, Liew cited a work of history rather than one of fiction as his inspiration for the book’s form: Roger Sabin’s Comics, Comix and Graphic Novels, a richly-illustrated work on the history of comics. Sabin lets each “document,” in its tattered materiality, speak for itself, a scaffold that is taken up in Liew’s work. In most instances, each page or frame in Liew’s graphic novel functions as a vitrine to hold real or fictive items from various archives: Charlie’s childhood drawings and his more technically honed sketches, photographs and posters from Singapore’s national repositories, and, of course, Charlie’s dossier of comics that span the twentieth century’s latter six decades. Structuring the novel chronologically, Liew provides fastidious annotations that guide the reader through the history of Singapore and the history of comics. Having worked through the meticulous captions myself, I would suggest that Charlie Chan is not devoid of a certain pedantry. Neither does the conscientious student lose out on opportunities for self-instruction; such a reader of footnotes will be rewarded with a reading list that is usually the purview of Singapore specialists and especially interested citizens. At its heart, one could argue that Charlie Chan is about making information available. The graphic novel is very much concerned with presenting the facts of history, which it seems to point out – one could even say, self-reflexively – through its appropriation of an historical work’s form.

Yet unlike a history textbook which offers clear exposition, the reader of Charlie Chan is placed on a vertiginous trail without handrails. This reader experiences a heady confusion as she navigates the individual page – and when she tries to gain perspective on the narrative as a whole. Various pathways of reading are mapped across individual spreads: does the eye follow the main comic strip in focus (Charlie’s “historical” work), the commentary in the form of captions, or the secondary strip that features a mop-haired avatar of Liew himself? As a whole, the graphic novel isn’t one text; it comprises many. It is a palimpsest, a layered narrative that allows us to see through and across its strata. In consequence, the process of reading is made an exhilarating traversal of historical and fictive time.

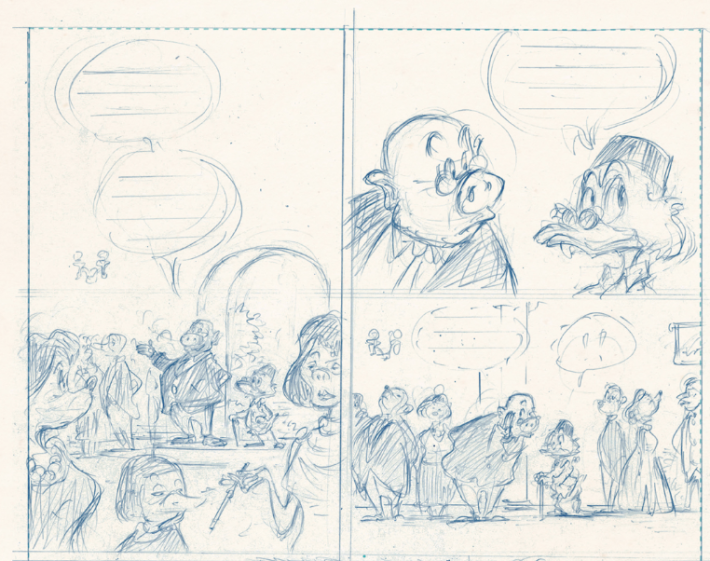

This open layering also results in moments of narrative irresolution. Consider “Dato Duck in Singapore,” a trenchant work of political commentary inserted just before the graphic novel’s close. Never completed by Charlie, the double-spread comic features an aristocratic Malaysian fowl who is eagerly whisked around a business-hungry Singapore by her suppliant denizens, drawn with canine and porcine features. No introductory remarks accompany this comic, nor does the strip fit into the chronologically sequenced presentation of Chan’s works throughout the novel, where individual comics always reference a contemporary political event. Remarkably, Charlie Chan’s most direct reference to postwar Singapore’s neoliberal economic system appears late in its schema. Problematizing Singapore’s capitalism in this way allows the critique to retrospectively haunt the pages of her history laid out earlier in the narrative. For the most part, the thematic of economics figures in the narrative as a pragmatism versus idealism debate pertaining to Charlie’s life. With the naming of a system in “Dato Duck,” our attention is drawn toward the possibility of reading Charlie’s preceding production in the light of structural forces.

“The retelling of Singapore’s history in the work potentially undermines the authority or legitimacy of the government and its public institutions, and thus breaches our funding guidelines”—on these grounds the National Arts Council (NAC) of Singapore, a statutory board of the state, revoked a publishing grant for the graphic novel. Indeed, every historical “retelling” involves a selection of facts. There is no such thing ever as an “objective” history. Yet I suspect the NAC’s statement operates on another reading, or even, I would contend, a misreading. The highly layered form of Liew’s graphic novel is far from a singular “retelling.” Another strange thing: this “retelling” of history is shot through with fiction – indeed, the work is less a “retelling” than a “reimagining.”

We can fathom the extent to which Liew bends or even disregards historical parameters by posing the question: who is Charlie Chan, and could there have been a Charlie Chan? A Singaporean boy with a prodigious talent for drawing, Charlie is a conduit for the graphic styles of postwar comics from England, Japan, Hong Kong, and, above all, America. Charlie’s efforts contribute to a small blossoming of comics in local presses. Herein lies one of Liew’s great reimaginings – Singaporean comics that resembled Charlie’s works did not exist. Singaporeans were indeed reading imported comics, but to my understanding they were treasured commodities because of their scarcity and cost. They wouldn’t have been as widely received as in their home markets. Charlie is an enigma in a novelistic universe that is built on familiar and historical grounds. For Liew, his protagonist’s name is an allusion to the eponymous figure of Wayne Wang’s film Chan’s Missing. We never get to meet Wang’s Chan although his unexplained disappearance propels the movie’s plot; we never quite pin down his identity, his traits, or his motivations.

Much in the same way, we never actually get inside Charlie’s head. This is both due to the form of the graphic novel and to the author’s adaptation of that form. An emblematic character, Charlie moves among winners and losers, heroes and antiheroes, and we are never in doubt about which side he belongs to. Created as the mirror image of the historical figure Lim Chin Siong, an opposition politician, Charlie is and remains an antihero throughout: moral, steadfastly loyal to his cause or art, a comic artist who creates but not a mere tradesman who illustrates; Charlie’s dedication to his art comes at the expense of a career and love. The graphic novel trades in stock tropes such as the romantic idea of suffering for one’s art, and the traditional hierarchy separating creative and commercial art. Charlie is also straight, male, and Chinese – he is not marginal by Singapore’s racial and sexual norms. Any psychological depth must be read onto Charlie: the reader must learn to read the slouching of a back or the tilt of a head, and observe physiognomic variations that shift from frame to frame. Objects are elevated to the level of characters in these comics. We learn of Charlie’s favorite beverages: the Milo tin and a glass of iced water are granted individual frames, while his arsenal of drawing utensils are lovingly portrayed and named in the footnotes. A quality of irresolution characterizes the figure of Charlie. His portrait is constituted by the comics that he draws, his objects, and the most external of his attributes – his frugality and his social isolation; the reader plays detective in putting together her image of the protagonist. At the same time, Charlie inhabits a world where narrative structures are simplifying and schematic – which I don’t mean as a criticism. Rather, I view the work of fiction as the structuring, condensing, simplifying, and sharpening of reality.

Liew’s embrace of an uncustomary figure puts into play one such narrative structure. Lim Chin Siong is an overlooked character, traditionally figured as a malcontent in a triumphalist history of nation-building. “A Singapore Story,” a caption featured on Charlie Chan’s special edition cover, brings to mind the similarly-titled autobiography of modern Singapore’s founding father, Lee Kuan Yew. Lee’s “official” account (“The Singapore Story”) describes his stewardship of the fledging state following its decolonialization; the histories of the nation and the man are intertwined. In Charlie Chan, Lee and Lim are cast as equally matched opponents, indeed, as superhero archrivals, each figure’s political existence mutually exclusive of the other’s. The book’s opening strips, set out on its colorful end papers, constructs this juxtaposition through mirrored four-by-five grids of talking heads. Lee’s square frames are richly filled with a full life, whereas Lim’s frames taper out poignantly toward the end. The real sting in these paired sequences is the repeated heading that introduces the comics, the Chinese proverb “One Mountain Cannot Abide Two Tigers” – a suggestion that the men are equally formidable and powerful opponents.

The graphic novel plays out this rivalry as the leitmotif of several comic strips. Lee is the cunning mousedeer of Malayan folklore to Lim’s cat in the “Pogo”-inspired “Bukit Chapalang.” In another comic strip “Dragon,” a cryonically-preserved boy wakes up to find rival, spacesuit-and-cape-clad politicians “Harry Lee Kuan Yew” and “Lim Chin Siong” struggling for dominance against the “Hegemonese” race. There is something dramatic, but also monolithic, about these stagings of Lim’s and Lee’s opposed characters. A shade of reductionism is unavoidable with such a boldly delineated juxtaposition, a reduction that is also the graphic novel’s provocation. Still, to take up once again the NAC’s terminology, this narrativization is an act of reimagining rather than “retelling.” The reversal enacted by the comic strip “Days of August” couldn’t be more fictively misshaped – and therefore different – than historical reality: Lim Chin Siong (appearing as himself) shrugs off accusations of demagoguery and dictatorship in a TV interview, having led Singapore into independence without merger with Malaya. In Singapore’s history, Lee Kuan Yew led Singapore into a controversial – and ultimately brief – political union with Malaya, while the negative associations arising from his decades-long helm as prime minister are likewise transposed onto the fictitious Lim.

I would argue that Liew’s validation of Lim over Lee is at the crux of the local controversy that surrounded Charlie Chan. Liew’s work was published in Singapore just over a month after Lee’s death, at a moment when the grieving country was – and still is – undertaking the task of renarrativization that necessarily follows loss. Singaporean establishment figures and a sizeable portion of her citizenry discredit “alternative” and “revisionist” histories as unequivocally factitious, labels which are often applied to Charlie Chan. It speaks volumes, I believe, when the strangest of fictions is taken with dead seriousness.

Is Liew’s novel deliberately pedagogical, radically imaginative, or schematically reductive? Ultimately, my three broad points are by no means mutually exclusive. Charlie Chan is generous in its show of love for comics and country, even if the latter’s most poignant manifestations are couched in critique. Liew’s complex and expansive work will always encourage new readings and rereadings.

This article reworks remarks from a recent discussion panel at the Second Singapore Literature Festival in New York City. Many thanks to Jee Leong Koh and Pek T.B. for their editorial assistance, and to Sonny Liew for his permission with image reproductions.

Y.S. Pek is a writer and graduate student who lives in New York City.