Cover Versions

From the archives (January 27, 2016):

If you were in NYC last summer, you might have encountered the work of Singaporean artist Heman Chong at the New Museum. Part of the group show “The Great Ephemeral,” Chong’s contribution involved visitors in memorizing a short story he had written in response to the exhibition theme. From the beginning of his career, Chong (b. 1977) has taken not only the image but also the word as fields for his investigations. In collaboration with Spring Workshop, Hong Kong, he co-edits, with Christina Li, an annual issue of short stories titled Stationary. The stories are written by artists, curators, and writers on residency with Spring Workshop. What’s again special about the distribution of Chong’s work is that the uniquely designed Stationary is mailed out free to anyone who wants it.

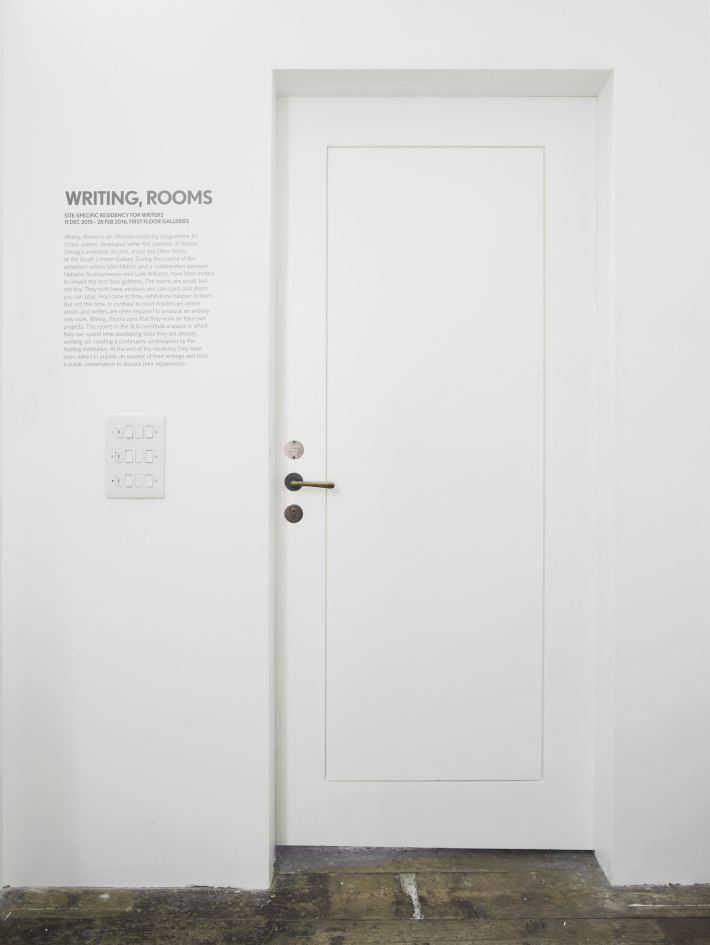

Heman Chong, An Arm, A Leg and Other Stories, 2015. Installation view at the South London Gallery. Courtesy the artist and Wilkinson Gallery. Photo: Andy Keate

Chong’s work is on display in two new shows, “An Arm, A Leg and Other Stories” going on right now at South London Gallery (until 28 Feb 2016), and “Ifs, Ands or Buts” at Rockbund Art Museum in Shanghai, China, from 23 Jan – 03 May 2016. The South London Gallery show features Monument to the people we’ve conveniently forgotten (I hate you), consisting of a million blacked out business cards covering the floor of the main gallery space; THIS PAVILION IS STRICTLY FOR COMMUNITY BONDING ACTIVITIES ONLY, an exact reproduction of a public sign in Singapore; and a wall of sixty-six paintings selected from three painting series: Cover (Versions), Things That Remain Unwritten and Emails from Strangers. There are also four new works on show: Inclusion(s), for which second-hand copies of novels have been collected in the gallery shop and made available for redistribution; Rope, Barrier, Boundary, which appropriates an appendage of many museum shows; an intimate and intense performance entitled An Arm, A Leg, happening every Wednesday at 1pm and 5pm; and Writing, Rooms, a residency program for fiction writers in the gallery.

SP took the occasion of his new shows to ask the artist a few questions.

Heman Chong, An Arm, A Leg and Other Stories, 2015. Installation view at the South London Gallery. Courtesy the artist and Wilkinson Gallery. Photo: Andy Keate

SP. Your website does not show the usual images of an artist’s website, but displays a short story instead. I think it’s a witty way of pointing out that all images are a kind of narrative and that the usual artist’s CV is also a kind of fictionalizing. The short story, titled “December 18, 1994,” is about a failed artist and his long-suffering wife. Embedded in the story is a “last photograph of them together,” seated at a bar with “pink cocktails” in their hands. In your artistic practice, you have been concerned to mine the relationship between word and image. What in your childhood and education led you to this abiding interest?

HC. I had a pretty standard middle class education in Singapore, going through primary and secondary levels at a neighborhood school (in Geylang) and finishing that off with a Diploma in Visual Communication, which is more or less a fancy title for a graphic design course at Temasek Polytechnic. My father worked in a garment factory his whole life as a manager and my mother ran a small accounting practice out of our home. My entire childhood had a soundtrack attached to it: a 8-bit dot matrix printer churning out endless rims of numbers. I left Singapore, both mentally, physically, in 2000 after I was done with our military (I refuse to call it national) service to study more graphic design at the Royal College of Art in London. I remember waking up one morning in London, regretting my years of studying graphic design. I don’t regret it now. I see it as a foundation for everything that I am doing: editing pictures, pointing to signs and symbols, composing words and sentences, conceptual pranks. An education in graphic design has been immensely useful, a kind of pragmatic no-nonsense kind of sweat-and-blood type of training. So, I guess that’s where I’m coming from, on most days. A training in putting things together on a flat surface.

Heman Chong, An Arm, A Leg and Other Stories, 2015. Installation view at the South London Gallery. Courtesy the artist and Wilkinson Gallery. Photo: Andy Keate

SP. The story “December 18, 1994” is also about various ways of telling a story. The first paragraph is straight narrative. The second paragraph is pure dialogue. In the third, the artist tells his wife a story about a man who claimed that Kowloon belonged to his grandfather and, to prove his point, painted his claim all over the city in calligraphic graffiti. The fourth paragraph describes that last photograph. The fifth is a list of public events, celebratory and catastrophic, that happened in the year of 1994. The list ends in the next and last paragraph with the private tragedy of the artist and his wife. The story thus juxtaposes different ways of telling a story while maintaining a coherent narrative arc. The same impulses to juxtapose and cohere seem to animate your on-going series of paintings of imaginary book covers, titled Cover (Versions). Different paintings of different book covers are put together differently in different exhibitions. At the same time, the paintings share the same size (61 x 46 x 4 cm, or 24 x 18 x 1½ in), the same font for book title and author’s name, and the same painting style. Does this observation seem true to you, and, if yes, how central to your work are the impulses to juxtapose and cohere? Is one stronger than the other? Is a work more successful when one is stronger than the other, or when they are in some kind of creative tension?

HC. To be honest, most of the the time, I don’t know really know what else is possible. I have a pretty short attention span, and I find it very difficult to stick to the point. I digress, things pull me away, other things pull me out even further. I come back to where I started with a bag full of shit. I sort the shit out, this one makes sense, this one I throw, this I keep for later. And this continues, every day in my life. I collect ideas, I write them down, and see if I can see use it for a later purpose, a future composition. Sometimes, I succeed in finding a good place for the material, sometimes, I don’t. I’m still learning, and I’m happy to learn. I don’t feel obliged to take on any kind of assumption about what works better. Things have a certain life of their own, and it’s important for me to respect how certain material are drawn towards each other, others not. I should also say up front that most of the time, when I’m making something, I don’t really know what I’m doing. I’m just making it up as the thing gets made. I improvise, change things, move things around. It’s done when it’s done. Sometimes it takes 5 mins (Monument to the people we’ve conveniently forgotten (I hate you)) to make a work, sometimes it takes seven years (Calendars (2020-2096)).

Heman Chong, An Arm, A Leg and Other Stories, 2015. Installation view at the South London Gallery. Courtesy the artist and Wilkinson Gallery. Photo: Andy Keate

SP. As the title of the short story indicates, you are very interested in the notion and experience of time. The story explains different ways of viewing the year 1994: “In the Gregorian calendar, it was the 1994th year of the Common Era, or of Anno Domini; the 994th year of the 2nd millennium; the 94th year of the 20th century; and the 5th of the 1990s.” In 2014 you held a solo show at FOST Gallery, Singapore, titled “Of Indeterminate Time or Occurrence.” In that exhibition, you showed a new work consisting of a neon sign spelling out NEVER / AGAIN, flickering between red and yellow continuously. How does the contradiction between “never” and “again” make sense to you?

HC. I curse a lot. Like a lot. Therefore, I like phrases that people often say to themselves, usually words muttered out of anger, or sheer regret, words of deep resentment. They often define a moment when you realize that a certain situation is really shit, and it’s all their fault and it’ll take a lot to get out of. I’m pretty sure we’ve all been there. These are the things that can connect us in a plain and simple, straightforward, no bullshit way. Something that can function without a metaphor. It’s a bit like what Rothko said about painting, I can’t really remember verbatim, but it’s something which goes; that a painting is not a picture of an experience, it’s the experience itself. Much like the shitty things that happen to us all.

Heman Chong, An Arm, A Leg and Other Stories, 2015. Installation view at the South London Gallery. Courtesy the artist and Wilkinson Gallery. Photo: Andy Keate

SP. You wrote the story “December 18, 1994” after meeting the Dutch writer Oscar van den Boogaard in Hong Kong in 2013. He was there as a Writer-in-Residence for “A Fictional Residency” organized by Spring Workshop and Witte de With Center for Contemporary Art. In your new show “An Arm, a Leg and Other Stories” in South London Gallery, you have three writers (Mira Mattar, Natasha Soobramanien and Luke Williams) work on their own writing projects in the gallery throughout the duration of the art show. At the end of the show, the writers will hold a public conversation to discuss their experiences. What do you hope to achieve by including the writers in your show?

HC. I don’t believe in putting the private act of writing on public display. I never have. I don’t think writing makes for a good performance. I think good writing makes for a good performance. The three writers are given rooms to write in, they can write whatever they want. The door can be closed. It’s not a performance that is visible. Don’t you wish sometimes you have a new space to write in? And that someone will give it to you without charging you for it? I can imagine it’s nice to have a new space to write in for 10 weeks. They receive also a small fee, as you would get with some residencies. In this case, I’m not asking them to write something new. They can work on whatever they are working on, so I’m not disrupting their work. I see it as a gift between artists, a one-time gift.

Heman Chong, An Arm, A Leg and Other Stories, 2015. Installation view at the South London Gallery. Courtesy the artist and Wilkinson Gallery. Photo: Andy Keate

SP. In the story that the artist tells his wife, the calligraphic graffitist gave himself the title of “King of Kowloon.” Some people believed his claim but most people thought he was mad. His failure in getting his claim recognized is, of course, a metaphor for the failure of the artist-narrator. In your view, does artistic success depend wholly, or mostly, on public belief in the artist? What is your greater fear, to be believed or disbelieved?

HC. I have many anxieties in my own personal life but I try very hard not to translate them into my work. Sometimes, things do slip out, for example, one of the most obvious is, of course, the fear that I am absolutely terrible at writing fiction, but I continuously attempt to write with a sort of naïve optimism that I might get better at it if I keep doing it, which is hardly the case for most. A lot of my visual work revolves around the act of writing, the product of writing, the circumstance of writing, but I’m never actually able to carry a narrative from A to B without failing horribly, for example, I often resort to appropriating whole chunks of text from some ridiculous source just because I feel that the story has to somehow maintain an assumed length, which is completely retarded. I don’t know, I have so many fears, if I write them all down, it’ll be enough words for a novel, I’m sure.

SP. Thanks, Heman, for your time. I hope your new shows find their best audience, or perhaps I should say, their best readers.

Heman Chong, An Arm, A Leg and Other Stories, 2015. Installation view at the South London Gallery. Courtesy the artist and Wilkinson Gallery. Photo: Andy Keate

Heman Chong is an artist and writer whose work is located at the intersection between image, performance, situations and writing. His work continuously interrogates the many functions of the production of narratives in our everyday lives. He lives and works on Depot Road in Singapore.