The Fiction of S. Rajaratnam and Singapore's Sense of Self

The Fiction of S. Rajaratnam and Singapore’s Sense of Self

by Manish Melwani

A talk delivered at the panel “Singapore: From Non-Alignment to Neutrality” on October 5th 2018 in New York, as part of the 3rd Singapore Literature Festival in NYC. Co-panelists: Ng Yi-Sheng and Joanna Phua. Moderators: Saronik Bosu and Heba Jahama.

Panel description: During the Cold War, Singapore was a member of the Non-Aligned Movement, which sought to form a counterbalance against the Western and Communist blocs. Nowadays, Singapore is regularly perceived as a “neutral territory” for the meetings of world leaders, including the Trump-Kim summit. Its critics, both local and abroad, charge that the country has never been neutral. It is, instead, a space of political contest, both within and without. How do the country’s writers respond to the various forms of state control without falling in with a Eurocentric view of the world? How do they negotiate with American cultural dominance without reiterating the politics of Singaporean exceptionalism? Is there a place, in literature and politics, for neutrality? If not, what is the alternative?

“Labour” by Basoeki Abdullah, oil on canvas, 195 x 293 cm. Source: National Gallery of Singapore.

Two years ago, back in Singapore for a holiday, I stood in the newly-opened National Gallery—the museum of Singaporean and Southeast Asian art that occupies the former City Hall and Supreme Court Buildings—looking at this enormous painting: Labour, also known as Building of the New World, painted sometime in the late 1950s by the Indonesian artist Basoeki Abdullah. Its descriptive text read:

“In this painting … Basoeki Abdullah depicted his aspirations for the Third World at a time when much of Southeast Asia was contemplating a post-colonial era driven by the labours of the common people … This artwork was presented as a gift (circa 1965) by former Indonesian Foreign Minister Adam Malik to his Singaporean counterpart S. Rajaratnam … and was for many years displayed prominently at the main stairway of this City Hall building where the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, together with many key government departments such as the Prime Minister’s Office and Ministry of Culture, were housed.”[i]

Looking at it, I felt a kind of awe at the scale of these aspirations, and then a deep regret for what might have been. After all, had we not turned our back on the Third World?

Like most Singaporeans my age, my most prominent association with the phrase “Third World” comes from the title of former Prime Minister Lee Kuan Yew’s memoirs, From Third World to First: the Singapore Story. I thought that Third World and First World referred to developmental states—the Third World was something to be escaped, something to disavow, while the First World was the promised land we’d arrived at through exceptional planning and hard work. Singapore had transcended the corruption, traffic jams and squalor of our regional neighbours, left it all behind to become a gleaming city-state on a reclaimed-land hill. Third World to First.

So I was shocked when, in my first semester of graduate school, a few months before seeing this painting for the first time, I learned about the Non-Aligned Movement, and what the Third World actually was.

In the words of historian Vijay Prashad, the Third World was “not a place. It was a project.”[ii] In the years after the Second World War, the planet split into two opposing poles led by nuclear-armed superpowers. The United States and its allies were the First World, the USSR and its allies the Second. The Third World were what Prashad terms “the Darker Nations”—newly decolonized countries comprising “two-thirds of the world’s people who had only recently won or were on the threshold of winning their independence from colonial rulers.”[iii] These countries dreamed of freedom, political equality and dignity, and in the hope of achieving these things, created their own bloc that would not side with American or Russian interests. This was the Third World: the Non-Aligned Movement.

Basoeki Abdullah’s painting, Labour, therefore represents the dreams of these newborn nations: dreams of destiny, dignity and solidarity. I wonder what the leaders of newly independent, newly decolonized Singapore—Lee Kuan Yew, S. Rajaratnam, Goh Keng Swee and others—thought as they walked by this gigantic painting every day. They must have identified with it, seen some reflection of their own dreams for the city-state they laboured to build. And as the years went by and Singapore’s developmental strategy increasingly distanced them from the rest of the Third World, I wonder how their feelings towards it changed.

Of all those leaders who worked in City Hall, the one who I wish I could ask about this painting was the man to whom it was presented: Sinnathamby Rajaratnam, because 20 years before he became Singapore’s Minister for Foreign Affairs, he was like me: a young man living abroad, trying to make it as a writer.

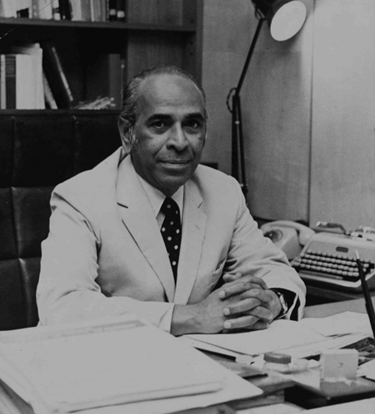

Rajaratnam in the 1950s. Source: National Archives of Singapore.

S. Rajaratnam was born in Sri Lanka in 1915. When he was six months old, his family brought him to Seremban, in Malaya, where his father was a supervisor on a rubber estate. At age 19, he went to Singapore (which was then part of Malaya) to study at the prestigious Raffles Institution, and after that to London to study law at King’s College. He never finished his studies: after WW2 broke out he found his calling as a journalist and fiction writer. His short stories garnered the attention of writers like E.M. Forster and George Orwell (who recruited him to write radio plays for the BBC). One of his stories, “Drought”, was reprinted in a 1947 world’s-best anthology alongside writers like Ernest Hemingway, William Faulkner, Franz Kafka and Rabindranath Tagore.[IV]

In 1948, Rajaratnam moved back to Singapore and became a journalist. He co-founded the the People’s Action Party in 1954. In 1959, they won the General Elections, and have been in power ever since. Rajaratnam spent the rest of his life in public service, first as Minister for Culture, and then, after Singapore separated from Malaysia in 1965, as Minister of Foreign Affairs. He helped draft Singapore’s National Pledge, as well as its foreign policy. He became Deputy Prime Minister in 1980, retired in 1988, and and passed away in 2006. The National Pledge was read at his funeral.

Now, Singapore doesn’t really venerate or nurture writers, especially not fiction writers, so the fact that one of the founding members of our political establishment secretly had these literary credentials was a significant revelation to me. What does it mean that S. Rajaratnam, a man who helped shape Singapore’s culture and foreign policy, was, in his early years, a fiction writer whose work seems invested in many of the themes and struggles of the Third World Movement? What does this mean specifically to me, a Singaporean writer living abroad, struggling to find my own definition of what it means to be from Singapore?

When we think about the Singapore that was built, about policies enacted out of the offices where this painting hung, we should ask: who built our nation, and for whom? Why did we build it the way we did? What did we gain, and what did we lose? We should ask these same questions of Singapore’s culture as well.

Singapore’s cultural and foreign policies during the Cold War

To quickly address Singapore’s turn away from non-alignment, we need to look at our foreign policy during the Cold War. In his 2017 book on US-Singapore relations between 1965 and 1975, Daniel Wei Boon Chua—who by the way is a professor at the S. Rajaratnam School of International Studies—outlines Singapore’s strategic balance between non-alignment (the Third World) and alignment with the USA (the First World).

Chua asserts that “the need to gain popular support from Singapore’s Chinese majority—who were sympathetic to the leftist opposition party” compelled Singapore’s government to publicly present the country as non-aligned.[v] But once we’d gained recognition from the non-aligned bloc, the Singapore government

… weighed the economic imperatives and began to increase economic cooperation with the United States. Singapore became a major fuelling station for US military vessels and a procurement centre for American military operations during the Vietnam War. American soldiers on combat leave in Singapore led to the growth of the island’s tourism and hospitality industries. But beyond commercial benefits to Singapore, the US military presence provided a psychological boost for Singapore’s security and economic stability.[vi]

This stability was further boosted by a dramatically increased volume of trade and American investment into Singapore between 1965 and 1975.[vii] After the Vietnam War, Singapore drew closer to the United States, abandoning non-alignment and beginning to take part in joint military exercises with the United States[viii], an arrangement that continues to this day.

It should also be pointed out that Cold War considerations shaped Singapore’s cultural development as well. Both the American and Singaporean governments were concerned that the Chinese majority would be more loyal to mainland China than to Singapore. To counter this, the PAP sought to “create a national identity and a common destiny for Singaporeans”.[ix]

The National Pledge that Rajaratnam helped draft is perhaps the most concise articulation of this identity. It calls on all citizens of Singapore to pledge themselves as ‘one united people, regardless of race, language or religion’ to work together to build a democratic, equal and prosperous Singapore.

S. Rajaratnam’s proto-Singaporean stories

Now, while the Pledge is an important and meaningful aspiration that I appreciate (especially as a Singaporean who’s part of an ethnic minority) I think it’s also really important to note that any culture shaped by policy frameworks and strategic considerations can only ever be just that—a framework. It falls to the rest of us to fill in the gaps and create something that’s honest, shared and enduring, grounded in a deeper place than policy. Something like a soul, if city-states can be said to have souls.

The Cold War ended a generation ago and history rolls on; the geopolitical circumstances that allowed independent Singapore to survive and prosper are rapidly changing. And we as writers, artists, citizens, need to construct a lasting identity beyond the one defined and articulated by the state after independence.

Reading Rajaratnam’s published short fiction, which predates independent Singapore by 20 years, I found myself thinking of it as proto-Singaporean literature, echoing the sentiments and concerns that were bubbling in people’s minds in the years leading up to decolonisation.

Most of Rajaratnam’s stories deal with rural life in South Asia and Malaya. He writes with style, wit, vivid imagery and a keen ear for the English language. He’s a writer interested in human folly, for example in the morosely funny story “The Stars”, in which the narrator’s uncle, an extremely self-serious astrologer, is obsessed with predicting the date of his own death in order to prove astrology’s primacy over astronomy:

According to Uncle’s horoscope, he was to die at the age of sixty-eight. He had even gone so far as to calculate the time and day of his death. He repeated this grim prediction to everyone as if the fulfilment of it would once and for all be an irrefutable proof in favour of astrology. There was something dramatic in the idea that Uncle had to die to establish the truth of his science.[x]

Rajaratnam the fiction writer is also interested in questions of class and exploitation, as evidenced by the ending of “The Locusts”, a story in which a rural community narrowly avoids having their harvest devoured by a swarm of locusts:

Thulasi laughed and laughed till the tears ran down his cheeks. It was as if his own crops had been saved. He was happy, happy for his comrades. Now there would be plenty for the hungry, wearied people … He was so happy he did not hear Naga Mudaliar call out to him.

“O forgive me, Mudaliar,” he apologised. “I was so engrossed I did not hear you. The locusts might have ruined these poor people.”

“The locusts might have ruined me, too,” said Naga Mudaliar, who owned most of the lands in the village, and was greedy for yet more. “Shiva be praised for that! Otherwise these rogues would have cheated me out of my dues… What is the matter with you? There is a strange look on your face.”

The happiness went out of Thulasi’s heart. He was suddenly thinking of Sangran, the moneylander, and of the tax collector, of the Brahmin priest…

“Nothing, Mudaliar,” said Thulasi. “I was thinking of one of the locusts a farmer crushed between his fingers yesterday. He crushed it and threw it away.”[xi]

Mudaliar, by the way, is a Tamil last name and title meaning “person of first rank”, sort of like a headman or a landlord, and in colonial Sri Lanka it was used by Europeans as a bureaucratic rank for local elites, and Rajaratnam explicitly links these men atop the hierarchy to ravenous locusts feeding on the common people.

His stories about rural life—“The Locusts”, “Drought”, “Famine”, “The Tiger”—reflect the struggle for dignity and equality that would eventually drive the aspirations of the Third World Project and the Non-Aligned Movement. Reading them, watching him develop as a writer over the course of the 1940s, one catches glimpses of a great Malayan novel never written, a literary career that never reached the heights it could have, the raw, bubbling fervour of the colonised world in the 1940s.

Part of me wishes Rajaratnam had continued to write fiction instead of going into government. Perhaps what we gained from his contributions in the public sphere, we lost in the literary sphere. Perhaps if he’d been more outspoken about his fiction, being a writer would be considered a more credible career choice in Singapore. That would be nice. But in any case, speaking as a Singaporean writer, there’s something quite thrilling about being able to claim an establishment figure like S. Rajaratnam as one of our own.

Singapore: an oasis for migrants and capital

Returning for a moment to the question of who built Singapore, and for whom, historian Ang Cheng Guan quotes Lee Kuan Yew as saying in October 1966 that:

The foreign policy of Singapore must ensure … that this migrant community that brought in life, vitality, enterprise from many parts of the world should always find an oasis here whatever happens in the surrounding environment.[xii]

Singapore has always been built by migrants. This has been true since 1819. Indian convict labourers were transported by the British to build much of early Singapore’s infrastructure. Chinese migrants sojourned far from home to what they called ‘Nanyang’, the Southern Ocean, hoping to find a better living there as labourers, dockworkers and rickshaw-pullers. They did not have comfortable or easy lives, much like the transient migrant workers today who labour to build Singapore’s expressways and skyscrapers built on some of the world’s most expensive real estate.

Migrant worker in Singapore. Source: The Straits Times.

In Jini Kim Watson’s book The New Asian City, she observes that Singapore’s modernity was envisioned “against the background of other third world locations also competing for investments of transnational capital”[xiii], and that our gleaming, well-manicured postcolonial city was in fact built to attract foreign investment as part of our developmental strategy.

Singapore is not just an oasis for its migrant community—it was also an oasis for First World capital in the Third World. Today, we claim much of that capital as our own. Singapore has one of the highest concentrations of millionaires per capita in the world. We’re a country that values the “5 Cs” of material accomplishment—car, cash, credit card, condo and country club, what Rajaratnam worriedly called “moneytheism”. In the era of Crazy Rich Asians, the ending of his short story “The Locusts” feels extremely radical.

While we’ve gained prosperity, stability and comfort from our rapid economic development—prosperity and stability that allows me to be sitting here at this panel discussion in New York—perhaps we’ve also lost something. We’ve lost our connection to the rest of the postcolonial world, and perhaps, caught up in our modern skyline and climate-controlled gardens, we’ve lost a sense of who we are and where we come from. In his aptly-titled poem “The Labourer”, Monir Ahmed, a Bangladeshi poet working in Singapore’s construction sector, writes:

Craftsman of this beautiful civilisation

the touch of your sweat has been erased

from the bricks of these mansions [xiv]

The problem with Singaporean exceptionalism—indeed, with any kind of exceptionalism—is that it ignores history. Skyscrapers don’t just build themselves. Ports don’t just boom out of thin air. So by all means, let’s celebrate our successes, but let’s also not forget the convicts who cleared jungle and dug canals, the migrant workers who build our skyscrapers, or, to paraphrase Daniel Chua’s in his conclusion, the uncomfortable fact that much of our prosperity and stability was built on the United States’ war in Vietnam.[xv]

As writers, artists and citizens, we need to look into ourselves and beyond ourselves, past biases and blinkers, privileges and prejudices. We must not shy away from history, horror or uncomfortable truths.

The artist’s job is to re-complicate culture

There is no one Singapore story. The migrant community that settled here was a wide and varied group, who came here on sampans and pinsis, on dhows and junks carried on the monsoon winds. We have always been a multicultural port city, with deep roots in many harbours across the Malay Archipelago, the Indian Ocean and the South China Sea. This recurring pattern of migration is perhaps the closest thing we have to a naturally-emergent identity.

In some ways, the workers who build our towers and highways have more in common with our proto-Singaporean forebears than we do—the coolie, the clerk, the rickshaw puller, the samsui woman, the domestic helper, the construction worker—these are the majority of Singapore’s origin stories, not just the few who have streets named after them. Looking back at our migrant history, perhaps we can broaden our definitions of what it means to be from Singapore, to be of Singapore.

In 1957, S. Rajaratnam wrote and broadcast a six-part epic radio play on Radio Malaya titled A Nation in the Making, an expression of his hopes, fears and dreams for a multicultural Malayan nation. In it, various archetypal characters debate the origins and merits of a shared Malayan culture and consciousness. One of them, simply named “A Malayan”, exhorts the others to:

…search the buried past—the stones, monuments, chronicles, folklore, language, religion, bones, names—all the curled, gnarled roots sunk in the soil of history.[xvi]

We would do well to do the same. We need these stories to ground us, to give us a lasting sense of self. Because if our identity was forged by the exigencies of a Cold War that has ended, and if the Singapore of Crazy Rich Asians and the Formula 1 Night Race is perfectly adapted to the neo-liberal boom times that followed, then what becomes of us when the vine on which we’ve flowered begins to wither? What happens to a small country’s sense of self when the world changes dramatically around it? Can we be an oasis for migrants in an era of mass-migration, an oasis for multiculturalism in an era defined by rising seas and rising walls?

If we are to do so, we will need to develop an identity that goes beyond national development and political calculations, to forge connections with our past and with each other. Because even if countries may not have souls, communities most definitely do.

A storyteller and his audience along the Singapore River, 1960. Photo by K.F. Wong.

Notes

i Wall text for Abdullah, Basoeki, “Labour”, Singapore, National Gallery Singapore, July 2016

ii Prashad, Vijay. “Introduction.” The Darker Nations: A People’s History of the Third World. New York: The New Press, 2007.

iii Ibid.

iv Rajaratnam, S., and Ng, Irene (ed.). “Introduction.” The Short Stories and Radio Plays of S. Rajaratnam. Singapore: Epigram Books, 2011.

v Chua, Daniel Wei Boon. “Conclusion.” US-Singapore Relations 1965-1975: Strategic Non-alignment in the Cold War. Singapore: NUS Press, 2017.

vi Ibid.

vii Chua, Daniel Wei Boon. “Chapter 5: Activating Singapore’s Economy: US Economic Diplomacy in Singapore.” US-Singapore Relations 1965-1975: Strategic Non-alignment in the Cold War. Singapore: NUS Press, 2017.

viii Ibid.

ix Chua, Daniel Wei Boon. “Chapter 1: American Containment and Singapore Survival: Finding Common Ground.” US-Singapore Relations 1965-1975: Strategic Non-alignment in the Cold War. Singapore: NUS Press, 2017.

x Rajaratnam, S., and Ng, Irene (ed.). “The Stars.” The Short Stories and Radio Plays of S. Rajaratnam. Singapore: Epigram Books, 2011. (“The Stars” first published in Indian Short Stories, 1946. Published by New India Publishing Co, London.)

xi Rajaratnam, S., and Ng, Irene (ed.). “The Locusts.” The Short Stories and Radio Plays of S. Rajaratnam. Singapore: Epigram Books, 2011. (“The Locusts” first published in Life and Letters and the London Mercury, August 1941. Published by Brendin Pub. Co, London.)

xii Lee Kuan Yew, quoted in Ang Cheng Guan, “The Global and the Regional in Lee Kuan Yew’s Strategic Thought: The Early Cold War Years.” Singapore in Global History, edited by Derek Heng and Syed Muhd Khairudin Aljunied. Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press, 2011.

xiii Watson, Jini Kim. “Chapter 5: The Way Ahead: The Politics and Poetics of Singapore’s Developmental Landscape.” The New Asian City: Three-Dimensional Fictions of Space and Urban Form. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2011.

xiv Ahmod, Monir (Shromik), and Lim, Vanessa (ed.). “The Labourer.” Songs From A Distance: Selected poems from the 2015 and 2016 Migrant Worker Poetry Competition. Singapore, 2016

xv Chua, Daniel Wei Boon. “Conclusion.” US-Singapore Relations 1965-1975: Strategic Non-alignment in the Cold War. Singapore: NUS Press, 2017.

xvi Rajaratnam, S., and Ng, Irene (ed.). “A Nation in the Making, Part III.” The Short Stories and Radio Plays of S. Rajaratnam. Singapore: Epigram Books, 2011. (“A Nation in the Making, Part III” first broadcast on Radio Malaya, 25 July 1957. Published courtesy of the S. Rajaratnam Private Archives Collection, ISEAS Library, Institute of Southeast Asian Studies, Singapore.)

Manish Melwani is a Singaporean writer. He attended the Clarion Science Fiction and Fantasy Writers’ Workshop in 2014, and recently completed his MA at New York University’s Gallatin School, where he studied science fiction and fantasy, postcolonial studies, and the maritime history of Singapore. Follow him on Twitter at @Manishmelwani.