Art Is + JinJin Xu

SP Blog’s series "Art Is +" is an attempt to view art through the eyes of artists and writers themselves. In wide-ranging interviews with vital new artists and writers from both Asia and the USA, the series ushers these voices to the forefront, contextualizing their work with the experiences, processes, and motivations that are unique to each individual artist. "Art Is +" encourages viewers and readers to appreciate art as the multitude of ways in which artists and writers continually engage with our world and the variety of spaces they occupy in it. Read our interviews with Symin Adive, Geraldine Kang, Paula Mendoza, and Zining Mok.

JinJin Xu is a writer and filmmaker from Shanghai. She has received honors from The Poetry Society of America, Southern Humanities Review, Tupelo Quarterly, and Cosmonauts Avenue. Her films have exhibited at Berlin’s Harun Farocki Institute and NYC’s The Immigrant Artist Biennial. A previous Watson Fellow, she is currently an MFA candidate at NYU, where she received the Lillian Vernon fellowship, teaches hybrid ballet/poetry workshops, and serves as Books Editor of Washington Square Review.

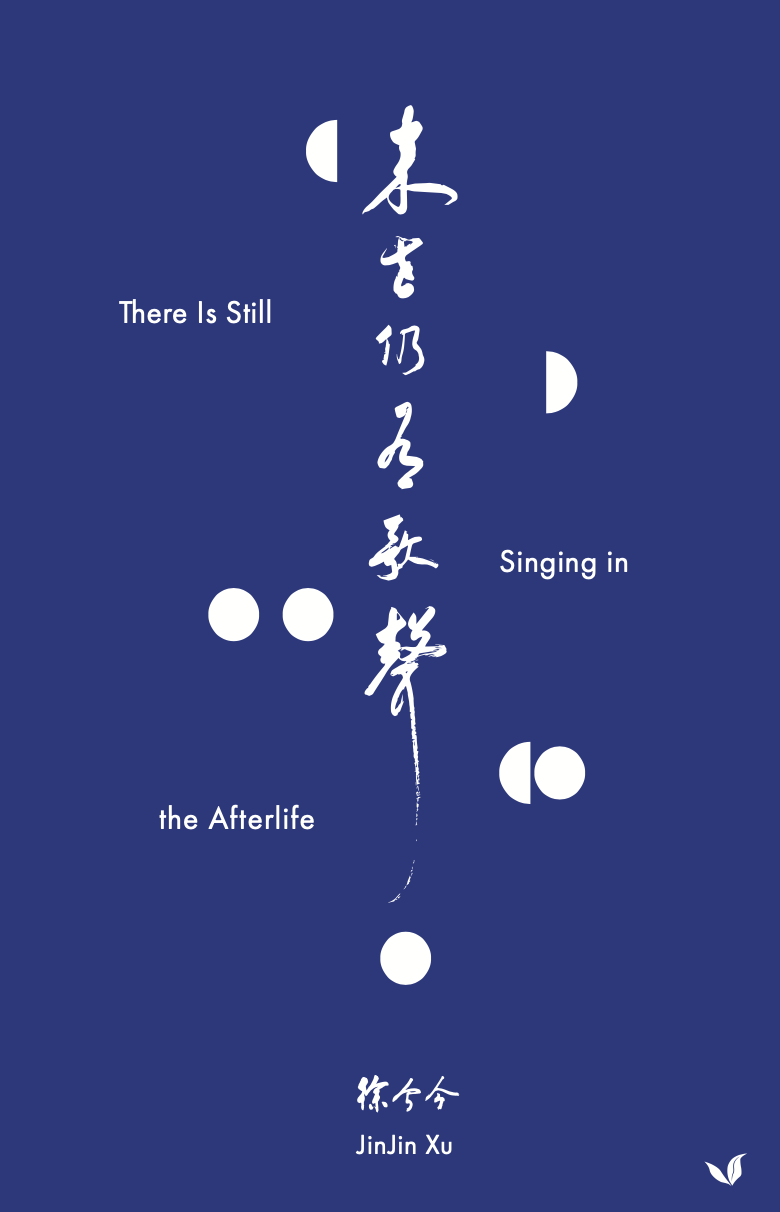

A poet of deep noticing, JinJin Xu’s There Is Still Singing in the Afterlife, selected by Aria Aber for the Own Voices Chapbook Prize, is marked by an unflinching gaze. Her work stares deeply at taboos and traditions worth interrogating, and speaks to them in a lush confessional voice. Terrance Hayes remarks that her lines “open and breathe on the page as they do in the mind and heart,” and describes the poems as “inventive, linguistic, ambitious, tender, wise, brave.” The poems in There Is Still Singing in the Afterlife resist the erasure of politics and memory, urging us to stay alive and probe both the light and its shadows. The book’s interrogation of how “people really do write their poems in their own blood, the way we can move to a new country and become masters of its language and poetry and still never be set free from the grasp of our homes, the way the dead refuse to leave us,” as described by Matthew Rohrer, speak to the power of language to preserve where personal and cultural memory exclude. Her voice is quiet, but firm. Listen.—Janelle Tan

“For me, English will always be at once a place

of freedom and betrayal. I want to view English as a language

to be molded. I want to use it to create

my private language, and for its insufficiency and betrayal

to become a place of imagination.”

Janelle Tan: What is a poem to you?

JinJin Xu: Honestly, poetry mystifies me. I’m not trying to be coy by saying most times I have no idea what a poem is doing, which is why I resisted writing poetry for a long time. Instead, I thought I was writing memories, moments that, I guess, become “poems” when they take on a certain rhythm of their own, propelling them into a space unknown to me.

Poems teach me the unknown, to trust that things and languages will keep their mysteries. Poems make public a private language, imprint songs onto my tongue, and make me feel alive—I hear and remember the pulse of the poet even after the words fade.

JT: Your book There Is Still Singing in the Afterlife combines many different thematic threads—elegy, birth family, chosen family and sisterhood, Chinese cultural history—when did you first begin to see how the threads came together? When did you realize you might be working on a book, not just individual poems?

JX: I didn’t allow myself to elucidate the so-called themes until recently, as I was putting together the final edits for the chapbook. For the past two years, I was just trying to write what feels most urgent and necessary and truthful—the only thing I am capable of writing, one at a time.

To understand the poems’ conversation amongst themselves requires me to step outside, to look with rigor and foreignness as a separate self. I did not want to fully understand, and thus limit, the project while writing—to fix it onto a pre-determined path—though I did, of course, know that I was always writing about the same obsessions, squinting through Borges’ Aleph to try and get a little closer to my naked self.

JT: How long did it take for the book to find a home at Radix Media?

JX: I didn’t dare imagine it as a book until Radix announced the surprising news. I probably never would have sent it out if I took it so seriously. When I feel lost, I like going to bookstores and finding the X’s, imagining my name amongst their spines one day. The “one day,” however, was indeterminately far, a pilgrimage not to be rushed.

So, I got very lucky. This was the first time I sent these poems out as a whole. While stuck in a quarantine hotel in Macau, without much desire to write, I slid these poems from the past two years next to each other and stepped back to see a fractal reaching for wholeness. The ordering was intuitive; I guess they’ve been fermenting together for a while.

JT: Memory and censorship play a big part of this book—the fallibility of both cultural memory, and personal memory. Someone described a poem to me once as a way of preserving emotional revelation. Do you think poems have the power to preserve memory, or document memory loss?

JX: If my poems could intimate a ghost of a memory—and like memories, be made anew—I am happy. The power and ability to write is a luxury I do not take for granted: writing shapes the way we remember, and always, I hold the responsibility of remembrance through my eyes’ limited reach.

Sometimes, I feel a sense of guilt when I write poetry because I know, in certain situations, nonfiction and documentary forms can be more directly empowering in their capacity for truth and reach. I am also attracted to those forms and, often, I ask myself, why does this need to be a poem?

I am wary of my impulse to hide behind language—poetry can cut to the core of truth, but it can also falsely elevate and aestheticize. My task began to make sense when I read Carolyn Forché’s Poetry of Witness—I felt less alone in my infidelity to this craft, my unsureness about my responsibilities as a writer, here, now.

JT: You’ve mentioned that Carolyn Forché’s memoir was particularly instrumental to your thinking about the task of the poet. What do you perceive to be the obligations poets have to their craft and to the world?

JX: I can’t speak about the task of the poet, but I believe every person should try to see the world around them clearly, to understand their privilege and right to look truthfully. This desire to see, to hold myself accountable to my truth, bleeds into my task as a person learning to write poetry.

JT: You still write fiction, and the book has a sequence that can be considered a lyric essay (both sections of “To Red Dust”). I know you consider yourself as someone who lives between genre. Is writing between genres for you a byproduct of cultural and literary hybridity? What is “genre” to you, and what is “form”?

JX: I still struggle to squeeze my work into a genre—even “hybridity” comes with its own conditions—and I feel trapped when I am tasked with a form before the idea takes shape. These imposed structures limit the possibilities of what I want to make. I have learned to trust the work to find home in its own container.

Genre, to me, is just the institutional shell within which my work is seen. A capitalist way of framing what is fluid and unknown. I have to separate myself from the work and ask, okay, if I were an editor, what genre would I see this in? This is mostly unnatural and unhelpful. So now, I just ask friends.

Genre, of course, is also a political choice. Authoritarian governments have long been afraid of poets for a reason and labeling something as fiction has its own subversive power.

“I flirt with documentary because I am fascinated

by the ethical stakes and questions

documentary raises . . . I am invested

in the constant erasure and revision of history and memory,

and I want to be aware of the fallibility

and limits of my own position.”

JT: I’m curious: what do you see as the role of poetry in an authoritarian state? How has a fear of possible retaliation and censorship shaped the way you share something, or speak to the truth of something?

JX: Censorship has shaped my commitment and awareness of my position to truth. It also taught me, from a young age, to read between the fracture of the history textbook, of a teacher’s lips, of overheard conversations between my parents, of what is unsaid inside a poem—to listen to what only the tilt of language is able to say.

JT: You were a fellow at NYU’s Screenwriting Production Lab and your book is inflected with documentary. Do you think a poem can be a document? How do you see your relationship with documentary, and how does documentary shape your poetry?

JX: I flirt with documentary because I am fascinated by the ethical stakes and questions documentary raises. It forces the maker to be aware of her positionality, of the camera’s power, of the way she is shaping the narrative.

I am invested in the constant erasure and revision of history and memory, and I want to be aware of the fallibility and limits of my own position. I grew up shaped by a history with censored holes, and in a way, my poems aim to write into the holes of my memory.

When the pandemic began, I started writing “Pandemic Diaries” inspired by Wuhan writer FangFang and exiled writer Yan Lian Ke, who said, "If we can’t be a whistle-blower like Li Wenliang, then let us at least be someone who hears that whistle. If we can’t speak out loudly, then let us be whisperers. If we can’t be whisperers, then let us be silent people who have memories.” Writing poetry didn’t feel right to me at the time, but I wanted to keep a record for a time when poetry calls on these memories.

JT: You have been working on a docupoetics project for as long as I’ve known you. Do you want to speak a little bit about that? How does that act of documenting feel different from the documentary of this book?

JX: I was fortunate to receive the Watson Fellowship after graduating college, which gave me the gift of a year to travel and pursue an independent project. I ended up traveling to nine countries speaking to, and writing with, women dislocated as refugees and migrant workers. When you met me at the start of the MFA, I had just returned from that year, and was feeling overwhelmed and lost in New York carrying the voices and memories and sisterhoods from that year. I didn’t know how to transcribe the memories they had entrusted me onto the page without letting them down.

I now understand I need more time before returning to that project. But the people I met, and the writing I did collaboratively, at times out of necessity as a translator for UNHCR, or as a messenger in a Thai detention center, or in a Turkish teahouse with mothers whose children have been disappeared, transformed the way I view the responsibility I hold to others in my own work. The stakes of writing, in these situations, were dangerously real—and yet, I also felt how feebly writing scratched the surface of such experience.

JT: For you, is the act of documentary part of the book’s remembering?

JX: In the chapbook, there are two poems written for a friend who passed away, written over the span of two years. For the longest time, I did not know how to grieve him without saying his name, which were his parents’ wishes. My memory of him shifted throughout these two years, fading and replaced by the words of these poems. That makes me sad, but the poems were also true to my memory of him when I wrote them.

My relationship to his sister also grew during these two years—now she is like a sister to me—and these poems became unstuck when I realized she is the one I was writing to. It was important to me that she would recognize his figure in these poems, while holding space for the slipperiness of my memory.

JT: The title of your chapbook as well the titular poem—There Is Still Singing in the Afterlife—both aim to preserve narratives beyond the passing. What does that mean for you in your work?

JX: I believe language holds the past inside it—like smells that awaken the lost, poems can trigger glimpses of a collective past.

JT: There is a thread of Chinese cultural history running through this book, like the Chinese epic Dream of the Red Chamber, and Mao’s Little Red Book. As a young Chinese poet writing in America, do you feel like there is an idea of what Chinese poetry looks like? Has that been a source of tension for you?

JX: I constantly feel like I am over-explaining myself. A qi pao cannot just be a qi pao, it is oriental, I never wanted to put one inside my poem. And yet, when I do eventually find myself writing about a qi pao, I am wondering if I should describe its buttons—which I wouldn’t do if I were writing in Chinese. It is unconscious, I do not know how to write without the gaze of Americans on my back.

Writing in English is already a sort of betrayal. But it is also my secret, free language—my parents don’t speak it—and it is the language where I came into myself, which also means my self in either languages is only ever half true.

“Genre, of course, is also a political choice.

Authoritarian governments have long been afraid of poets

for a reason and labeling something as fiction

has its own subversive power.”

JT: I’m curious then, how poetry started for you. When did you realize American eyes were starting to influence your poems?

JX: I ended up in a poetry workshop on my first day at Amherst College because the fiction workshop was full, and my advisor insisted that I try the less popular poetry workshop instead. From the very first day, I knew I did not want to write a poem that I would then have to explain to my class of white peers. And to me, any poem about my life prior to Amherst would require explanation—so I wrote about strawberries, not knowing that in America, strawberries are a summer fruit. I then watched the students discuss the metaphor of eating strawberries in winter. I nodded along because I did not have the language to explain how even the smallest things I take for granted can be misunderstood.

JT: You are a bilingual writer whose manuscript is predominantly in English. When you sit down to write, do you contend with your relationship with English and your mother tongue? Does English ever feel like an insufficiency?

JX: For me, English will always be at once a place of freedom and betrayal. I want to view English as a language to be molded. I want to use it to create my private language, and for its insufficiency and betrayal to become a place of imagination.

JT: I know you sometimes work in Chinese, especially in your multimedia projects. Part of translation is also translating cross-cultural references and ideas, and I’m wondering how you strike that balance between preserving and translating when doing so for your own work.

JX: I used to think that everything I write in English is an act of translation. But that hasn’t been the case for a long time, ever since my imagination slipped into waking in English. Instead of constant translation, I am more writing into a space in-between the two languages, one is never without the other—my task then, becomes, how do I expand this slippery liminality?

Translating allows me to see my own language anew—when I was on a tight deadline editing the chapbook, I ended up spending the majority of my time meeting another deadline: translating my poems into Chinese for an anthology. The coincidence of the two projects ended up being a great gift. By stepping away from my English poems, and chewing them over in Chinese, I was able to edit them with renewed clarity.

JT: I want to talk some more about the two sections of “To Red Dust” that are in the book. In it, a dust storm acts as a conduit to tell the story of the body, memory, and recollection. How did this analogy come to be?

JX: The poems spring from a desire to understand “red dust”—a “place” which has inflamed my imagination ever since I first heard my father utter it. “Red dust” is essentially located in a Buddhist way of seeing the world— referring to the earthly plane of our lives. I cannot define it, let alone translate it, which is why these poems are obsessively footnoted with repeated attempts to define “red dust.”

It is a mythological, inarticulate place, yet it is the only place we have language for. “For sight to pierce red dust” is synchronous to transcendence. To escape it is to no longer have the language for it.

“Poems teach me the unknown, to trust that things and languages

will keep their mysteries. Poems make public a private language,

imprint songs onto my tongue, and make me feel alive.”

JT: Both sections of “To Red Dust” feel very much like where the book is firing all its cylinders. It is ambitious not only in how it depicts Chinese politics, Buddhist monks, and a kind of taboo way of seeing family and the body, but also in its form. The poems, like the rest of the book, shines a light into dark cultural and personal crevices. Do you ever feel like there are certain things you cannot publish, or cannot say in your poems and therefore make public?

JX: Yes, which is why it would not be appropriate to say it here.

JT: Your work is also deeply intimate and tender. “Confessional” poems have sometimes been considered by more academic poets as lacking intellectual depth, but in this book and the rest of your work, it is a great strength. Do you think earnestness is a valuable trait in poems?

JX: I wish I understood wit and irony. I value directness, and Sharon Olds’ poems (and personhood) inspire me to live and speak earnestly. What else are we doing here together?

JT: As a writer living in New York City with a deep connection to your home country, China, who do you think your poems are speaking to? Who do you write for?

JX: I want to say I am writing for myself, but that is not true. Poems feel most true when I have a specific person in mind—whether addressed to a friend or a lover or someone who I trust as a reader. Actually, my favorite way to write is after reading a poet’s work that so moves me, I hear a distant ringing that urges a rhythm into my hands—or it can come from a shadow in a film, a face on the news. Writing poems allows me to be in conversation with people I wish to be speaking to.

Poems from There Is Still Singing in the Afterlife: “There They Are” and “To Her Brother, Who Is Without Name.”

There Is Still Singing in the Afterlife is available for preorder from Radix Media.

Janelle Tan is a Singaporean poet in Brooklyn. Her work appears in The Southampton Review, Nat. Brut, The Boiler, and elsewhere. She holds an MFA from NYU, where she was Web Editor for Washington Square Review. She is a Brooklyn Poets fellow and Assistant Interviews Editor at Singapore Unbound.