Absolute Control: Illustrating Marylyn Tan’s “Nasi Kang Kang”

By Kelly Sadikun

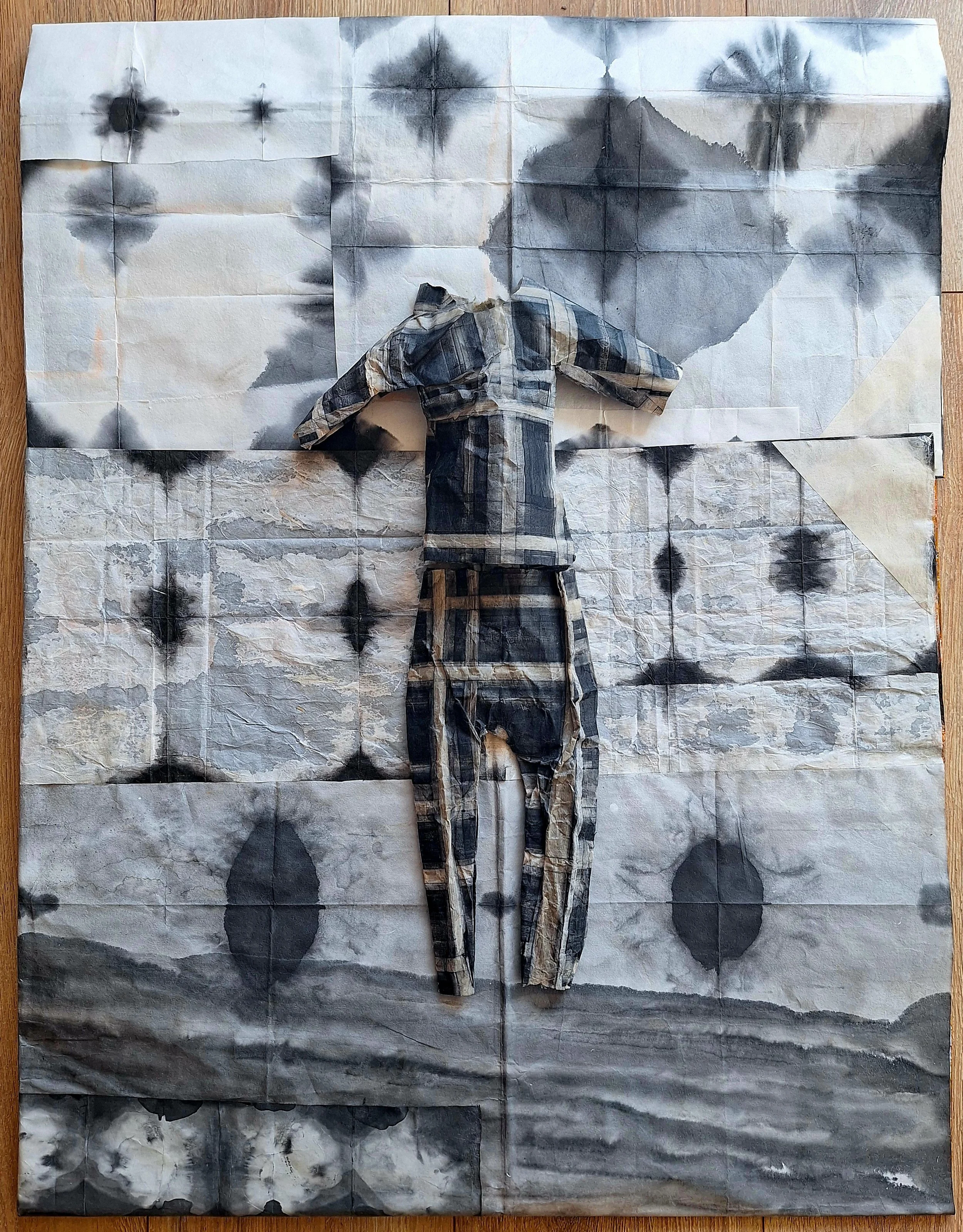

“Nasi Kang Kang,” drawn by Kelly Sadikun, inspired by Gaze Back, by Marylyn Tan (USA: The University of Georgia Press, 2022).

For my final project in fulfillment of Professor Brian Bernard’s class on Southeast Asian Literature and Film at the University of Southern California, I was inspired to create an artistic representation of Marylyn Tan’s poem “Nasi Kang Kang” from the collection Gaze Back. In this creative report, I will discuss direct elements from the poem that are represented in my drawing, followed by elements that came to mind as I critically engaged with the poem upon my first read and then on my second read after hearing from Marylyn Tan on her philosophical outlook during our class interview with the poet.

I was inspired by the Thai horror films we screened in our class to emulate the cover of a horror graphic novel in the layout of my drawing. On the top left corner, the title Nasi Kang Kang can be found with the vowels replaced by unicode symbols. Specifically, the letter “A” is replaced by the inverted, black, triangle symbol, which Tan described as representative of “pleasure as intrinsically tied to guilt… the unconscious mind… generative properties of the womb.” I chose this symbol because “Nasi Kang Kang” is about the practice of feeding rice with one’s menstrual blood as a means of having “absolute control” over a male lover, and the triangle seems to share a similar theme of a woman’s reproductive system being tied to what it could give — to bear children or to pleasure a man — rather than the pleasure it could receive, or just its existence as a body part. Additionally, I chose to replace the letter “A” because it is known as the scarlet letter that carries the dual meanings of “adulterer” and “able.” The letter “I” is replaced with the black moon Lilith symbol, which Tan described as “fertile chaos…the incarnation of lust… child-killing witch… embodiment of destruction.” I chose this symbol because of the repeated theme of fertility in the poem, and because of the line in “Nasi Kang Kang”: “witchcraft comes naturally to women.” The letter “I” also acts as a pronoun and brings the viewer directly into the piece so as to engage with it. Only the symbols have menstruation blood dripping from them, and the blood eventually forms the words, “Absolute Control,” which is taken from the line, “google said, according to malay folklore a woman who feeds her husband or boyfriend with nasi kang kang can have absolute control over him.”

I was inspired to draw a bride as the focal point by the line “there’s not much difference between a wrestling & a wedding ring,” especially because the cultural expectation for women is often for wifehood to be the end goal. The bride has physical features that appear to fit typical Asian beauty standards for women — for example, she is pale, which yields “ATTRACTIVE’ = +1.” She also has a body type that can be described by the line “be both curved & skinny as a sickle.” Lines taken from the poem are strategically written on her body like tattoos, such as “swallowing your pride” written on her throat, and “residential rights” written where she is squatting, referencing the line “I had a vision of a woman squatting over food like she was exercising her residential rights.” The only exception is the line on her thigh, which I have amended to read “these thighs were made for waterlogging,” instead of “these thighs were made for walking not waterlogging.” I chose to make this omission because all the other quotes affirm stereotypes and expectations for women. Similarly, “good girls swallow” and “only to please” written on her devil horns indicate the bride’s supposed willingness to fall in line.

The bride is squatting over a Philips rice cooker, letting her menstrual blood drip over it as if she is in the process of making nasi kang kang. Her somewhat vulgar position creates a sense of irony as it is juxtaposed with her prim and proper facial expression and appearance — looking solely at her face versus looking at the drawing as a whole yields a completely different impression. The rice cooker is also symbolic of the Earth, suggesting that not only does she have absolute control over men by making nasi kang kang, but she also has control over the world since the world is run by patriarchy, and her power over men thus gives her power over all. Following the space theme in the poem, the background of my drawing features a starry galaxy, with the bride’s figure looming large. The galactical background also adds a futuristic element to the piece, the juxtaposition of which emphasizes the long-standing nature of this cultural ritual still practiced in this modern day and in the future. Her size relative to the Earth and galaxy is indicative of her immense power and also likens her to a Zeus-like god. This disproportion in size suggests that as much as there are unfair expectations placed upon women, there is immense power to be gained by conforming to these expectations, but it also raises the question of at what cost?

To answer, I have hidden elements in the drawing meant to make the viewer question the bride’s self-awareness. These are elements not necessarily part of Tan’s poem “Nasi Kang Kang,” but interpretive details I added in my own artistic freedom as I was inspired by Marylyn Tan’s discussion in class. For example, the sparkles around her body and wedding ring are blue and pink (colors of the bisexual, pride flag,) and they refer to the line “if “bisexual”: “ATTRACTIVE” = -1, “FICKLE-MINDED” = +1.” These sparkles suggest that her supposedly less attractive quality, perhaps her queerness, literally shines through, no matter how much she tries to comply with social conventions. The bride’s wedding dress and veil, as well as her devil horns and tail, are purposely exaggerated to look costume-like, as these are qualities externally forced upon her. She is forced to pursue wifehood, so she wears a childish, princess-like wedding dress with a tiara veil. She is told that women are witches, so she adorns herself with demon horns as she is called “self-possessed.” Her left eye, upon close inspection, is actually a glitch, which makes the viewer wonder if this ideal woman is real at all, or merely a constructed image. Ultimately, the takeaway of this drawing is for the viewer to wonder if the bride is complying with societal expectations out of coercion, or for her own gain, or if the answer is in the middle.

Kelly Sadikun graduated summa cum laude in 2023 from the University of Southern California with a double B.A. in Political Science and East Asian Languages and Cultures. As a Chinese-Indonesian American, Kelly is passionate about uplifting the Southeast Asian minority community and learning more about her culture. She is currently pursuing her J.D. at the University of Southern California’s Gould School of Law and hopes to eventually serve a global audience in the Asia Pacific region.

If you’ve enjoyed reading this article, please consider making a donation. Your donation goes towards paying our contributors and a modest stipend to our editors. Singapore Unbound is powered by volunteers, and we depend on individual supporters. To maintain our independence, we do not seek or accept direct funding from any government.

What consumes us? Three poems by Alison Clara Tan.