Violin-Wallah

By Niranjan Kumar

Hanreality - Falling in Love, Digital collage

Image description: A black-and-white cutout of a man and a woman is in the center of the collage, against a vivid red background. The two figures look at each other. Yellow spheres halo both their heads, and the couple is framed by a wreath of yellow marigold flowers with green leaves.

I couldn’t find a place that would accept me and so I had to accept this place, and Abhay, as usual, was the one who found it for me.

“Not much work, and decent enough pay.”

He’d told me at the sidecar stand, with a smoking cheroot butt between his fingers.

“Um,” I’d said.

“Don’t be so glum.”

He threw the butt into the dirt, and squashed it underneath his slipper.

“It’s only temporary, and, besides, the pay’s nice.”

“The pay, huh?”

“Yeah.”

He lit up another one; he always had a series of cheroots, mostly sheaved in plastic, peeking out of his shirt pocket. And as he lit a new one, he replied for me.

“This is just work, right?”

“Uh. And what have you been doing for work?”

“Huh…. Nothing, nothing at all.”

“Why don’t you take it then, Abhay?”

“Well, because I have a steady enough job, and you don’t.”

“You still with the circuit?”

“Um.” I asked for a puff with an outstretched palm, and he handed me a new, unlighted one. I placed the end to my lips and he lit the tip aflame. It breathed acrid, then melted, to a mellow, juicy taste, or perhaps it was just my ulcer acting up, or perhaps I didn’t even have an ulcer, just told myself that for a considerable number of reasons, and of course, most likely, and lastly, from the plastic bag of three-day old biryani I had skimmed off from a wedding I had performed for. I had asked because I’d wanted to know if he was still painting, or writing, it was clear that he hadn’t been, and wouldn’t be, if he was still with the circuit.

I exhaled. “Show me it, then.”

“Why didn’t anyone take this job?”

“I don’t know.”

He still had his cheroot, he was running down to his last, and he was going to ask me for some money soon, before he left, and I would pay him, because we had come to develop an unspoken pact, to see each other through our endeavours, for the simple reason that no one else would.

“I don’t mind the—this place, I don’t think anything about it, I can’t find a reason why anyone else should.”

“Don’t bother me about it. Hey, want to listen to some of my drumming?”

“No.” I set down my violin case on a small stand. There was some dust on the stand. “And I don’t have to clean?”

Abhay shook his head, and I turned back to catch this glimpse of movement. “Okay. Do you need some money?” He flicked off some ash from his last remaining cheroot, and grinned. I smiled back at him.

Hanreality - Marionette Show, Digital collage

Image description: Against a black backdrop, a faceless puppeteer dressed in white pulls on the strings attached to a similarly faceless puppet. The puppet wears a colorful costume and performs in front of an abstract, dark blue wall. In the foreground of this composition, the cutout of a couple rendered in the miniature-painting style and dressed in traditional South Asian clothing look towards a large, painted marionette mask.

It wasn’t so quiet that you could’ve called it midnight just yet, but everything was dim and calm here, and the worries that usually haunted me have faded with the towering height of this place, between it and everything, the distance it embraced, and I was at the peak of that distance, lingering, and looming from my window, and there was nobody to see me, up here, from down there. Abhay had left me with some curry and some rice, in tied plastic bags, hung upon a nail. I didn’t want to eat up, just yet. I was too busy, looking into the depths of what I had left behind, and what grinned back at me, the empty desires that tortured us all. It was nearly meaningless, but there was a light beauty in the world that I couldn’t have found down there, and yet, that was where it was, and, only with separation had I finally discovered it again. I turned back, and walked a few steps, picked up the violin case off the small stand. It felt heavy; I replaced it on the stand, and stared through the window again. And well, then came the world of the night.

Abhay hadn’t told me much about the job, he just told me that I had to live here, and that someone would come, and slide an envelope full of money to me under the door on a day-to-day basis. The amount was unspecified, but he said that it would be more than enough for me to live on. I didn’t care, I just lay on the floor, staring off-handedly at the soot and cobweb-whipped ceiling. The space was like an empty cave or a dead and dried rib-cage of a whale. I didn’t have a mat to lie on, but I had my longyi and I spread it out on the concrete floor and lay upon it, trying to keep it and my back warm. And it should’ve been a nice night, if not for the heat and the humidity that soon crept into this place with me, and so I had to get up, and set up the small fan on the little stand, which resembled a ball of dirt with revolving blades, and I was afraid for a while that it wouldn’t start or that it would blow up or something, but thankfully it did not, and I had a nice cool-enough night at the beginning. But when I was lying on the floor, the urge to pick up the violin came back to me, and it wasn’t really so much an urge, but more a need, a pressing desire—just this once and I would never again have to, but in truth, it would ever demand your freedom from you. And so I didn’t budge an inch. I wouldn’t be able to see the strings anyway.

“Not that I’d ever stopped,” I’d told him.

“No, but you’ve really stopped playing.” His eyes were lit by the single overhead, which wasn’t so brightly lit, but his eyes, they seemed angry. I couldn’t look at them. Huh… damn you Abhay, not like you’ve ever accomplished anything, but wait, hadn’t he?… Yeah, he had, he had done something, while I’d never even made the front page. He had? What had he done? He built a fine stadium once, and got fired for it, and had never gotten any credit, but he knew, and he made it to the front page once, for starting a fire at that same stadium. He was in fact quite happy to have been caught, it made him feel somewhat important, when he was lesser than dirt on most days, and barely noticed. And I wasn’t there, then, when he required my assistance. But he came, and he always did come around. I really didn’t know why, I wasn’t ever there then, even when he required my help with the fire, or with anything. There had been only this one time, this one time when I’d watched over some things that were needed for the stadium to be built, and they ended up getting stolen anyway. I had nearly lost my violin, I did lose one of my strings, but then I played him a small tune the next day, and finished with a full-fledged solo venture by the night, and he slept, as if nothing had ever troubled him; and then, as now, we and our work were adored by no one. I didn’t mind it anymore, not that I ever did, I wasn’t ever going anywhere. I had simply been keeping watch.

The envelope was slid under the door. I found nothing in it, but dull and pointless paper. I sealed it, and waited. I waited for the hunger, I waited for the frail itch that wouldn’t come, staring at the clasped violin case. I waited. I didn’t know what to do with what I didn’t hold, I didn’t know what to do without the music playing. It was then that the old radio from a corner, which I had forgotten all about, started to sound out a tune. I could remember it very clearly; it was what I had played for my sister’s wedding. A song from a very old film, a Bengali one, I believe, a song where a wife sings for her husband to not fear, to be strong, and to be near her. It was on the night, I believe, of their wedding; it was a lovely song, the beautiful woman died in the next scene, leaving the estranged and disillusioned man, a child, and there were, I believe, a couple of lines and notes and scenes after that, but the one tune that I truly loved, besides the nuptial song, was found at the final point of reconciliation, between the man, Apu, and his daughter, named after the moon, I believe, or the mother, and perhaps both, and him wandering away with his child. It slowly broke my heart every time the tune came to mind; the tune died, and so the woman’s song ceased, and he cried, abandoning his child. And there was the Kaagaz ke Phool tune too, and that one wet the soul with blood. And I couldn’t find the right mind to pick up the case, and so I let it be, and I still waited.

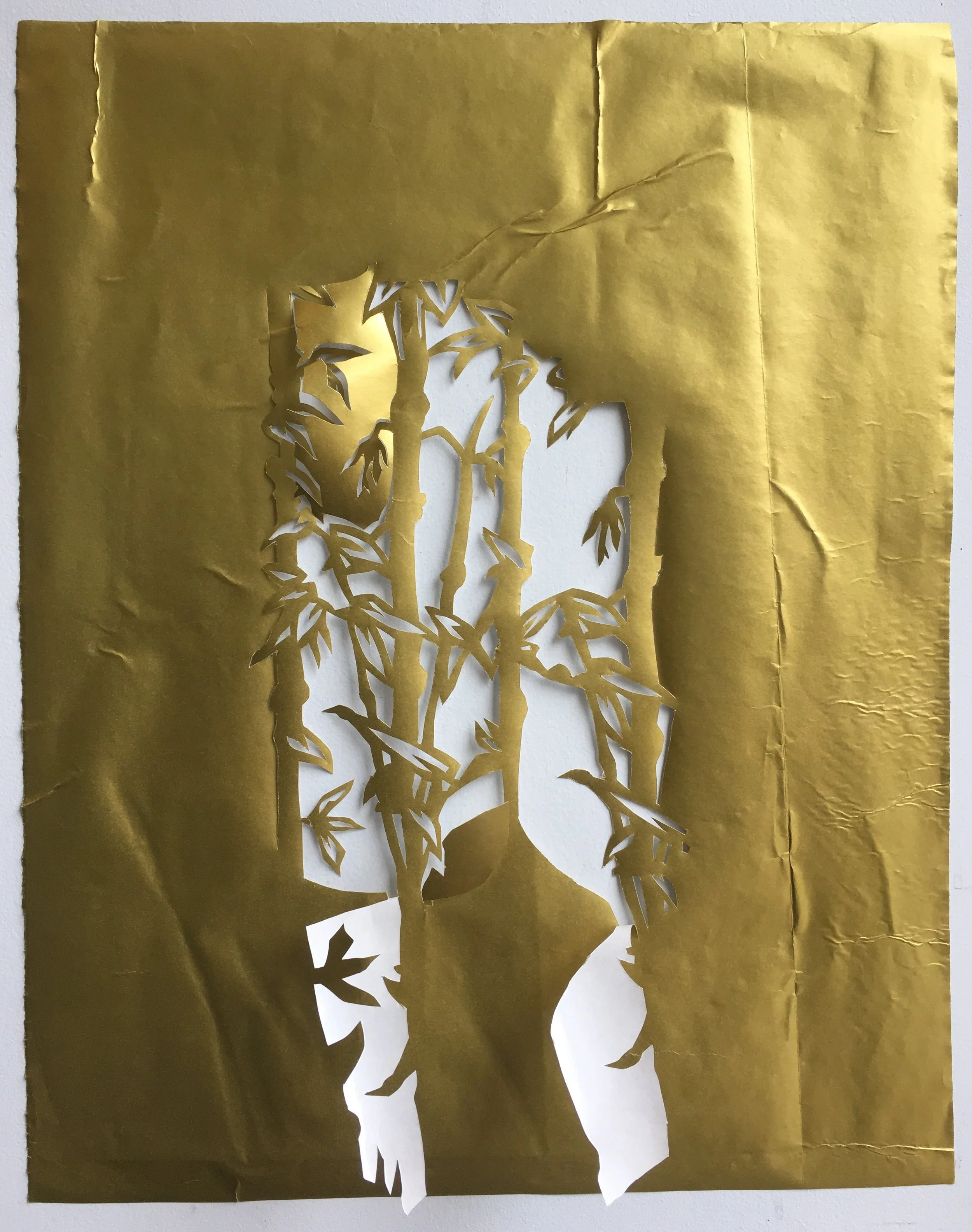

Hanreality - May the Whole Universe Hear Us, Digital collage

Image description: Against a bold red background, a vertical strip depicting a view of the galaxy shoots up from a cutout of a silver vessel. Layered on top of it is a bamboo stick with a red flower at the end of it.

The hunger struck again at the untimely hour of four-twenty, and I unhooked the two bags from the nail. One rice and one mutton curry, and they were stale. Uneasy eating, for I soon noticed the sour smell of the rice and I got nauseated as I ate, but it was food and it filled the stomach, and it satiated a need that often struck, and as such I was done with eating, quickly. Slightly drunk, I lay back onto my longyi mattress, dreaming off into the ceiling, webs and the ribs of a rickety old roof in view, and there was that lingering smell of rice that had gone stale, everywhere. I let the small fan on the stand rest for the moment, and decided to brave the heat, but the humidity succeeded in proving to me my thorough lack of determination, and I turned on the fan. And as I got up and shuffled to push the switch, I noticed the case lying by the small stand, and I lingered a while, staring, but then the switch was pushed and the sudden whirl of the fan pulled me away from the case. As my ears were pulled to the whirl, the music settled itself into the droning of the fan. I imagined the sounds, and they were sweeter than anything that I could’ve played. I lay back down, tuning off into the ceiling now, whistling an imitation.

I had started by playing for Abhay’s wedding, and ever since then it had been a whirl and twirl of weddings and nightly performances at certain venues and for customers I would rather not mention nor dream about. I didn’t blame him, even now, it was me who had taken the jobs, and he had just shown me where, which, and when, and had told me for whom, and how and why I should accept them, and I usually did, because I was always poor, even now, and he would find it so humorous whenever I accepted a job. Taunting me with the line “Live life in your river, and you, the fish, hooked and baited, you die; for you’d swum against it in vain.” He had laughed, happily. He had married my sister, Ragadara, and she had passed after the incident with the fire. I wasn’t there when it happened, like I’d said, I was somewhere else. They had married quickly, and were somewhat happy for a time, until the fire, right around after the construction equipment and materials were stolen. They had a pretty grand time for a while; and I was paid very handsomely for the time, for it was my sister who had paid me and it was still her marriage, and she had gifted me this violin. But the marriage was ended by the fire. It was almost like he had desired the end, it was almost like he had wanted for her to pass, but there was nobody after him, except me, who became like his son. And after me? I see but a shadow. Well, the violin case, if I was lucky enough, it would stay after me, and I thought for a moment to scratch some lines and words on the underside of the case’s cover, perhaps my name, but decided against it. The violin was pure, it needn’t be spoiled, or any more spoiled, more accurately, at least not by me. So I let it be, still, not even to scar or destroy it could I pick it up.

I could still see and hear Ragadara’s smile and voice; they were beautiful. She was my half-sister, and I should’ve married her; if only I had the wealth that Abhay had gotten for himself and my sister. But she had passed without leaving much behind, and he had lived happily while in prison. When he was released he didn’t mourn her, he just took to his roots of song and dance, and left everything of his recent past behind him. I had accepted that everyone had their own way of mourning, and so had I. I hadn’t touched the violin again for some time, not even the old and faulty ones that I would sometimes borrow to play. At least he had done something, and I hadn’t, nor had I touched her violin since, still in the case that I would always carry around with me, the case that was the only thing separating me from my deepest tears and regrets. The bare essence of her heart and soul was sealed inside, along with what was once mine. I imagine I would find it pristine if I ever were to unclasp the case, but I did not wish to.

Hanreality - Scary Nights, Digital collage

Image description: A disembodied hand reaches out towards the viewer in the center of the black-and-white image. The hand is attached to puppet strings, controlled by another disembodied hand that extends from the upper edge of the image. This composition looms above urban buildings against a gray background. The left building has a derelict wall, while the right building has a clean, white facade.

Niranjan Kumar Rai (Niranjana Rai) is twenty-three, and has been published in a few online publications and periodicals, such as the Wilderness House Review and Aruna. He was born in Mandalay, Burma. He now lives in Rangoon.

*

Hanreality, 1999

Collage Artist

Born and raised in Mandalay, Hanreality is a digital collage artist whose creations transcend time and groove to the beats of vintage aesthetics and rap melodies. He blends the reality between the past and the present through the art of collage. His creative journey began in 2020. He is a digital storyteller where each collage narrates a tale, woven together with fragments of vintage photographs, textures, and the soulful resonance of rap lyrics sometimes. His distinctive style has been recognized in the Shi Exhibition which was held in Yangon in November 2022. His collages were the example where pixels meet poetry and vintage vibes to find a new resonance to explore the intersection of time, music, and digital expression. He was also an EMPM residency artist who went to France for six months in the spring of 2024.

‘The first clean air came quietly. Felt wrong, almost. Like walking into your house after a funeral.’ – A short story by Ian Mark Ganut.