The Tale of a Fading Islet

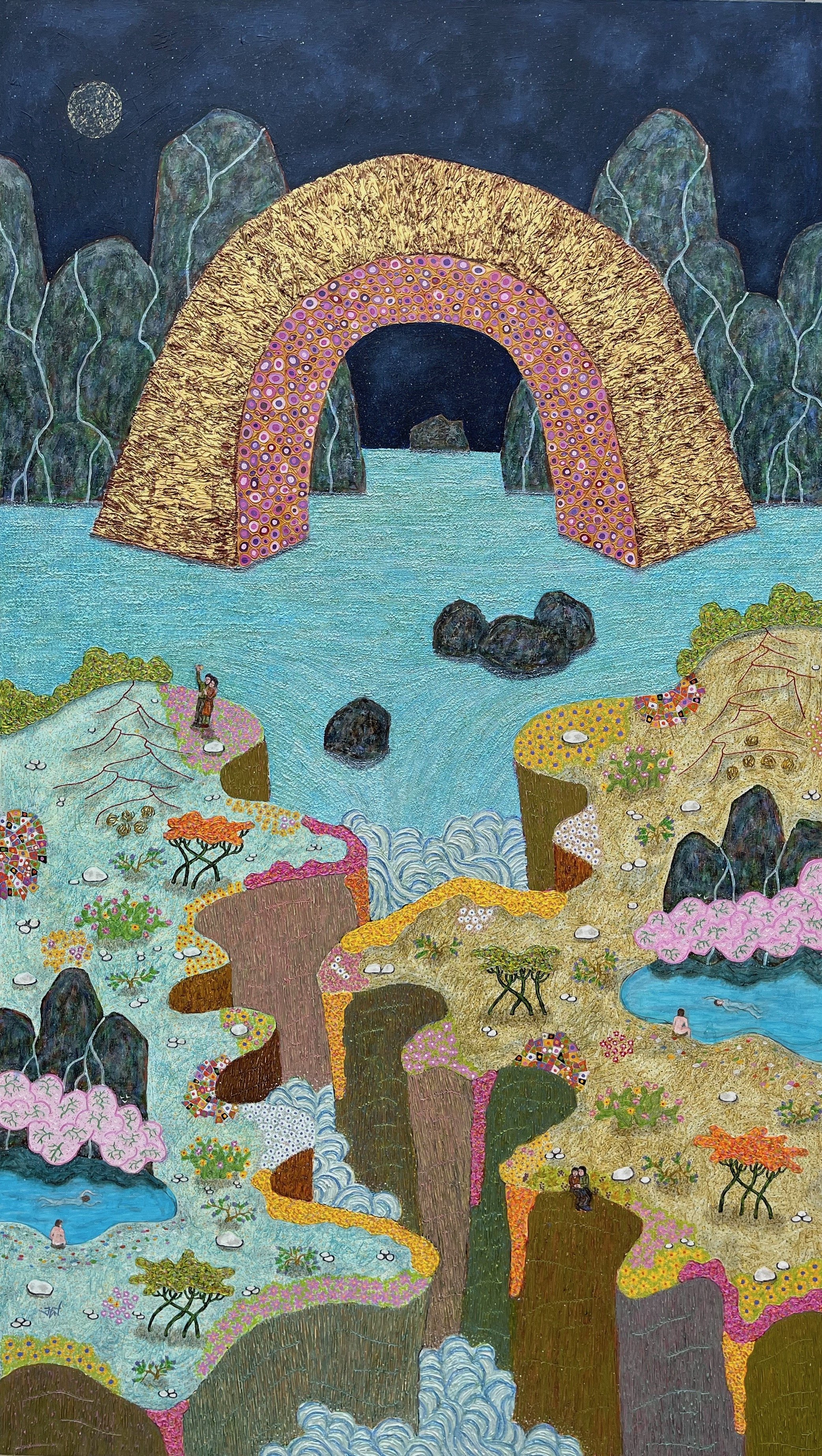

By Khải ĐơnHung Viet Nguyen - Sacred Landscape VI #17 (2023), oil on canvas, 84 inches x 48 inches

Image description: The colorful painting depicts a whimsical landscape consisting of a rainbow-shaped arch standing in the background of a canyon. A stream of water flows between two rocky terrains; their surfaces are covered with colorful trees, flowers, and small ponds. Minuscule human figures engage in various activities, such as swimming or sitting by the cliff.

Three hundred years before the night human faces floated mysteriously out of the water, a village existed among the passage of crocodiles and the meandering ghosts.

The gods didn’t have discerning shapes yet; they sat by the giant roots of thousand-year-old trees; they hovered among the strips of yellow sesban flowers; they wiped their feet on the velvety plains of reeds. Villagers had to row their boats through two moon seasons before they could catch sight of other human beings beyond their tiny village sheds. Yet no one thought of leaving the muddy patch or being curious enough to seek for other realms. Their lives were entangled with the mangroves’ roots, sucking deep into the alluvium and water; their fates were impulsively changed with ebbs and flows.

The village was just the stretch mark of soil and sand lingering among the high tide and low ebbs from the breathing river’s movement. Sometimes the river heaved like a grunting buffalo, other times it sighed as quiet as the butterfly’s flaps. Giant crocodile teeth acted as the protective barriers separating the human world and water life, by the gray and muddy horizon behind the thick sedge grass. Wild boars sniffled the smell of dry leaves on greasy mud paths. They rammed on piles of leaves and twisted mangrove branches, crafting their mysterious morass, their tranquil rolling and tossing site among themselves.

The ghost egret flocks swirled in the sky, shadowing the clouds into dark liquid patches. Their claws broke branches of peachy star flowers, scattering the river with dampened petals after rain. Villagers lived among that universe, shaken by touches of elements, quietened in scents of the air. They didn’t mingle with the beyond world; the horizon was unaware of their existence.

Once, a daughter got lost by the Crocodile Creek. Her mom beseeched the giant mother crocodile, who called all the crocodile shoal to line up in order for the poor mom to cross the swift-flowing creek to search for her daughter. The mom caught her daughter’s hand just in time, before she would have been charmed by the death lily and fallen into the mud whirpool. They ran home hand in hand, the daughter’s giggles gloaming on the water. Her eyes met the smile of a boy riding a giant mud carp afar on the horizon. Both of them would think of each other for many rice seasons to come.

When the rice ears bloomed for the tenth season, the little daughter, now a daring young woman, met that same boy, who had grown into a fisherman. He gave her a hand, which she grasped and climbed onto the giant mud carp’s back. Her hair flickered his cheeks like billowing smoke. They rode through the rapids to the islet’s point, where the fish glanced them goodbye and left. He cut down bamboo tree; she split the laths, weaving the front roof of their newlywed home. His eyes were caught among her fragile fingers; his heart was the home she dwelled in.

Not far from the couple’s bamboo hut, by the riverbank, where the sand was silky as ripe mango skin, kraits wrapped one another into dreadlocks, moving on many giant tufts. The snake’s eyes were slit in the middle, staring at the sun with the intensity of cold blood. It was said that the kraits guarded the village soil; their sensitive skin could feel the temperature change, sense the vibrating earth, and smell the soft sediment falling into place.

*

One morning, when the kraits were entwining into tufts, the villagers heard a blunt thud of a heavy metal object from high above, as a giant dark shade approached the edges of the soil. Pieces of red meat spewed on the goldren sand, tracing the shaken fate of the island. A giant rusted anchor slashed into the soil. The King Krait saw his life partner’s head drop onto his belly. His thick muscles flexed. He glared at the ugly hooks and blades recording the first mourning day and shot himself into the water. He spat out the rustic water before gliding away.

The shadow of the giant metal ship covered the shining sun, its side body as dark as a hell no one had ever seen, its metal front as sharp as a swordfish beak aimed at naive eyes watching them. Villagers squinted their eyes to see what had submerged their homes in the gray and dampened air. The metal ship grinded the pebbles, and a screetching sound cut the riverbank’s soil. The tide went high; maybe that was why the ship could sneak through the mangrove forests. Now it risked the chance to return to where it was from because water rarely got that high in this river.

The fisherman and his wife, now old and blinded, touched their fingers to the disappearing sun. That was the last time they saw the direct sun, blocked by the ghosting shade of the black ship; no one could tell clearly if it was day or night anymore. He wished that they had ridden the giant carp away for good since the early day of their youth. Suddenly, he couldn’t fathom which was real: the fish or this cruel ship piercing through their island. The brute ship prevailed.

*

Hundreds of years later, the beginning of the story about the village would churn out of the mouths of river people as this: Long long ago, nights and days smeared into illusion.

The utmost illusion started with a tall, pale-skinned man stepping out into the ship deck. Many more heads followed. Their hair was long and greasy, bundled into rags, as if they had suffered months of no shower or water. They stood by each other, eyes jaded, looking down at the soft sand and the small villagers approaching out of curiosity. The blind woman felt the scene from her high terrace of the stilt house; she mumbled, “The light has gone.” Her fisherman husband joined the villagers in the crowd below.

“From now on, this place, this village, is put under my sovereignty. You villagers, through your fishing, collecting, and farming activities, are subjected to a one-third tax. Otherwise, you are not allowed to go near the riverbank and exploit the natural reserve of wealth.” The pale man declared, his face stretched out with grand words, his teeth caked with yellow tartar; his eyes as green as the moaning cat’s, his arms coveting the fragile islet from the high board. His cheeks twitched as if he were a bad omen.

“What does it mean to be one-third? Do I need to split a lotus seed I collect into three parts? One-third of fish is what part? Is one-third of a water eel the head or the tail? Why are we subjected to give you this? Who are you, strangers? You have no right to collect anything from our sweat!” The blind woman struck her walking cane onto the soil, making thud thud thud out of the vibrating earth. Her hoarse voice echoed on the metal ship and bounced on the deck, inquiring the pale face to respond.

“One-third means... one-third.” Pale Face was embarrassed; maybe he didn't know the lotus seed only split into two halves; and asking for one-third of everything was so absurd that nobody argued except this blind woman. “We bring the order from your king. We are the ambassador from the gods you are blessed to have this soil to live. Your ignorance never questions where all your fish come from? Without the hands of God, none of this would have materialized.”

“Did the god create you?” There she was again, her blind eyes aimed at them on the deck, insisting on resolving this nonsense. Murmurs among the villagers arose. The pale man didn’t respond to her.

“He can’t answer. Of course he doesn’t know anything. Our river is created by no one. The river created us.” The old lady burst the silence with her statement. The pale man now knew who was the dangerous among these naive people. He licked his thin upper lip.

“Dear villagers, with the mechanical and modern physical strength, we blasted out the Crocodile Swarm and slit all the krait tufts. We protect you from the threat of the nature. We guarantee you a safe path to civilization. We crushed the toxic mangrove roots under our metal ship, forged through the fire of thousands-degree heat. Listen to our call from our God, find your way to the great faith to our great cause of civilization." The Pale Face continued his speech with an affirmative charisma the villagers had never encountered. People got confused between two powerful voices: one said that they belonged to the river, the other called them to the great civilization. They grew silent in the magnitude of the future they couldn’t fathom.

“The river created us!” The blind woman declared, spitting out saliva and striking her sickle, which was as thin as the young moon. The sickle flew its course, swerving through the group of people, aiming at Pale Face and brushed his cheek, a tiny red strip rolled down from the cut. He could feel his blood smell. The sickle flew back into the hand of the blind woman as quietly as it left.

Behind Pale Face, a bulky body walked up. This man had a big black beard almost covering his entire face; his posture contributed to the ship's shadow, obscuring the sun. He held something giant with his massive muscular arms, lifting it up and throwing it down on the golden sand. The sand splashed. It crashed heavily on the ground. Blood oozed out of its edge. The crocodile’s blank eyes reflected the life she no longer had. Her jaws opened loosely. The head was cut off from the chunky body, now rotting somewhere in the muddy water. The mother crocodile’s jaws and head on the ground illustrated the power of the new world slipping here through their slippery tongues.

From the right side of Pale Face, a tall and charming woman stepped down to the staircase and put her feet on the islet of far-flung mud roofs. Some men on the deck followed her with lecherous eyes, following her hips’ swaying movement. Pale Face showed his unhappiness by moving his yellow snake eyes, memorizing the faces of the drooling guys on his own deck.

Her feet left marks the golden sand; the first stranger to touch the path to the far-flung islet. She walked to the group of women and snatched a breastfeeding baby away from the mom’s nipples. The mother screamed and the baby cried angrily, thrashing in her pale arms. She held the baby higher than her head and said:

“We have the best intention for your babies, bringing them new health, new taste, and new future. We feed them as tall as our best soldiers, training them to be as tough as our hands. We breed you again in the evolved path of choice. Do you love that idea?” The woman’s tongue was green, some villagers noticed.

“We do! We do!” Thirty men on board cheered loudly. The mother was still struggling with her empty hands that suddenly bore no weight of the living creature she was nurturing. No woman responded to that statement; their silence was stampeded by grunts and hoots smearing the islet with a new air of excitement.

Green Tongue dropped the baby back to the mom’s arms. She didn’t say thank you, the mother reckoned when putting her nipple back to the baby's tiny mouth. It fell asleep sucking.

*

At night, the blind woman dreamed she was bathing inside the stream of thoughts. The thought strains pulled her down, and she was drowning in her own saliva before her fisherman husband woke her up and tried to choke the water out of her lungs. She breathed like an exhausted moon dog.

The next morning, the sun was orange in the murky gray curtain. The light lost its after-rain clarity, the air transparent, bearing the light scent of cat-eye grass. The blind woman heard her husband's echoing voice, “Let me go! This is my fish! Dare anyone touch them!”

“Every fish passing by this entrance to the village is taxed. The riverbank is our village sovereignty; didn't we tell you that yesterday afternoon?” Green Tongue picked the fish head up and examined it.

“The riverbank is not yours. It belongs to the river.” The old fisherman’s voice stiffened in bottled-up anger.

Passerby gathered, drawn by the noisy argument. Some nodded, some shivered with the truth, some shook their heads. Yes, the riverbank belongs to the river, to the mangrove forest, to the crocodiles who created the paths…

“You killed The Mother Crocodile. Those who kill crocodiles of Mother River are murderers. You murder for no reason. You will not touch our fish,” the fisherman raised his vocal cords. His forehead creased.

“The crocodiles threatened people. Don’t you see that obvious, old man? Are you embarrassing yourself with ignorance?” Green Tongue tried to flip the story to her side. The villagers seemed to side with the disgusting beheaded crocodile, especially if they needed to pay the a one-third tax for everything.

Black Beard rose behind Green Tongue like a mountain. His features threatened the light and diverted the wind flow. The air went quiet; even the big flock of birds eating sour berries lost their appetite and left the quandary. The fisherman raised his spear, aiming at Black Beard’s heart. Villagers gathered by the fisherman’s side. Their shadows accumulated into a giant shade, larger than the immense shoulders of Black Beard. The silence sucked up the air.

Then came the sound of clapping from the ship, accompanied by the grinding sound of metal shoes. Pale Face made his way from the high board down to the crowd's heart, standing by the fisherman, holding his calloused right hand and raising it overhead. Pale Face’s voice tore the stillness.

“Thank you so much for your civil interaction today. Today is so special, among other special things, we had our first community debate. Today, free tax for all entrants, a celebration for everyone with this shared understanding.” Thirty pairs of hands surrounded the villagers, clapping with all their might. Their faces smiled big while their shoulders encircled the farmers like a ring of fight.

The villagers were dazed; they dispersed and nervously left for home. The old fisherman looked into Pale Face's eyes. These eyes don’t have a soul, the dangling fish behind his back murmured. He smells like death, the fisherman wanted to respond.

Hung Viet Nguyen - Sacred Landscape VI #44 (2025), oil on panel, 30 inches x 24 inches

Image description: A colorful canyon is depicted against the backdrop of a mountainous landscape. Soft shades of green, pink, blue, and yellow are used to paint the ground, cliffs, trees, and water. Round, circular shapes resemble brightly-colored rocks or plants. The painting is heavily textured and rendered in fine, individually discernible brushstrokes.

*

The blind woman heard her husband step toward the porch. He grasped a coconut scoop and poured cold water from a clay jar onto his head. She laid out the softest sedge mattress for him, though it was stained with old sweat. He dried himself with the black and white kroma, its check patterns looking like the maze they were confined in. The old lady massaged his tense shoulders, easing the tendon worked up from waiting for the spear to launch. His arms stiffened; his fingers clutched into fists; his neck craned, ankles hardened as old roots, toenails digging into the bamboo sandals, leaving stretch marks. The blind woman gently released his fingers, waking him from his anger.

“Were you afraid?”

“Someone pointed metal rifles at me. I felt its cold mouth behind my back. I was not afraid.”

“Were you afraid?”

“The fish mumbled that I would lose to them. I was worried that you wouldn’t have food.”

“Are you afraid?”

“I am afraid.”

The blind woman and the fisherman sat in the cracking sunset. They waited for the dark to drape its blanket over the village. The next morning, he went out fishing in the lowering tide, but he would never return to the front porch of his beloved woman.

*

The next night, Green Tongue sent the thirty men from the metal ship to knock on every villager’s door, inviting them to a welcome barbeque party. They offered a piece of meat to every family, raising the metal cup with the red liquid with their other hand. Alcohol evaporated into the dense fog.

The big fire jumped and flickered to the clanging sound of cold metal musical instruments. Some villagers were told that the strings were sharp enough to cut off their fingers. Their eyes squinted in the reflective liquor, their ears numbed and gripped by the whining music which drowned out the songs of spotted toads and gray frogs from the jungle. Villagers exchanged skeptical eyes, but they were keen to enjoy new delicacies from an unfamiliar land.

Metal grills gripped the exotic fresh vegetables which sizzled in the fat from fresh-cut meat. Red as night eyes, embers extended their rosy-red tongue up to the flesh above. Sometimes, the fire flew high and curled into blue strips; local people used to call the blue fire goddess’ velvet. Green Tongue illustrated to the villagers that it was just the burning animal fat in high heat; dripping fat whipped up into a magical blue streak. She could create as many goddesses’ dresses as she wanted if she had enough meat.

Not only a goddess, she smirked. Villagers whispered in admiration.

Children ran around the fire, waiting to grab the sizzling meat skewers flavored by the smoke. Villagers couldn’t resist their own yearning. They stuffed their bellies with good meat, loud laughter, and volatile friendship into the deep night.

The party gradually wound down as drinkers dozed off. People piled up on their party mats and slept. They stopped dreaming of the goddess’ dress and forgot the gods who wandered through the grass land.

The blind woman sat as still as a bronze statue. Her husband left home early in the morning, and no one told her about the party. At midnight, she woke up when the porch was wet with moisture from the river; but she couldn’t hear her husband’s heartbeat. Was it too quiet, or had it already stopped permanently? He must have befallen the same fate as the fish he caught by now. She knew it yet she surpressed this acknowledgement in her lungs.

She sat up and fumbled around to find her walking cane. She asked the gray frogs what direction her husband took this morning. A toad on the longan tree frowned and muttered, it saw the old man walk to the Krait Pond, there was a shallow stretch that he could throw his net there.

Following the song of the toads and the complaints of old frogs, the blind woman walked the path to water. A thin krait wove itself onto her neck and whispered that she should slow down and turn right. Her foot hit something hard, clanging into it with a transparent and quiet sound.

She bent down and reached for a thigh bone. She kept collecting more pieces under the moon, collecting and counting, arranging and imagining. Some slipped off her palms. They were still wet with pieces of meat left. The bones giggled as if she was tickling them, as if the fisherman was laughing when he heard her tell him about her falling into the muddy hole when she was in a hurry to date him decades ago. As if they were truly together forever, and he was not just bone fragments in her hands.

She collected all the pieces until she reached the water of the Krait Pond. She knelt and bowed to the thin krait, to the frogs and toads. She told the water to tell her husband that she would be fine; everyone had been kind to her. She dropped the bones into the deep water; now she needed all the courage to return home, to the village of people who ate her husband's flesh tonight.

After saying farewell to her husband, the blind woman sat crying by the pond. The tears of a couple losing each other in the whirlpool of nights and days, of sickness and greed, of a sudden separation they didn’t prepare for. At first, her tears dropped one by one, and then her body started to lose its visibility; her hands went transparent, and her body slowly loosened into drops of tears she offered to the river. First, her palms and arms fell, then her chest, shoulders, hair, eyes, ears, and lips. Then her hair flowed into the young river where she had deceived the grand mother croccodile as a teenager so she could become a strong wife. All of her memories would stay here amidst the water.

*

Waking up from the party, the villagers went about their life with the feeling of something missing that they couldn’t comprehend. They went to the river, scooping and carrying water home to drink, wash clothes, or cook. They worked through dim layers of memories, submerged with longing and forgetting. Their souls wandered off unknown paths.

In the meantime, the settlers were cutting the final four legs of the last son crocodile. They were curious to see if they cut all four legs, the crocodile would still swim. Pale Face watched the young creature struggle to cross some meters in the mud. It lost balance, overturned, and drowned in the mud graveyard like many others of its kind.

At dinner time, villagers poured soup and recalled something they couldn’t name, someone they knew; some emotion had emptied down the bottom. Their families, children, husbands, wives, all became detached names, meaningless to their longing. Sometimes, their blurred sorrow turned despondent and craving, like hungry water.

On the fifth day, the metal ship decided that the river was a waste of space. They turned the ship prow to gore on the soil edge. The soil fell like a metal rain, river turning red. After ten nights without moonlight, they created a new stretch of land double the size of the islet. The new dyke cut through the flesh of land. Settlers celebrated their god-sent power with an endless flow of drinks, the smell of alcohol evaporating into the morning dew.

The villagers’ longing grew into a bottomless hunger. They bit into their arms to hide their yearning. They sucked their fingers to restrain themselves from doing something unthinkable. The children bit their moms’ nipples without budging. The mothers frowned and licked their teeth.

On the twentieth night, the sedge field was on fire. The gods and spirits walked the edge and jumped off dead cotton trees, leaving the toads and frogs to die with open mouths. Did the gods leave their people for good? The village was silenced in the smoky sky, layer after layer, until humans couldn't see human faces anymore. Only smoke and fog played in their fields like a game of ghosts.

On the thirtieth night, the settlers drank from the tip of the coconut trees. Villagers walked down to the pier, collected water, preparing their rice pots as usual. The smoky fog hid the stale posture of drunk settlers, some dropping asleep on the sand, some sitting among the burnt mangrove roots. The villagers’ blood rushed with a sudden, inexorable desire. All cloudy thought cleared up in their head, as if the sediment had quieted down and left a transparent stream.

That thought whispered into the villagers’ ears, exhorting them to walk in one direction, one step after another.

They arranged the drunken settlers into piles. They undid thick tent tarps and draped them on settlers’ bodies. They warmed up the space by sparking light from a fire-making stone and blew the fire up with dry straw.

The villagers finally comprehended what itched their days and nights: they longed for the blue fire and grilled smoke of dead meat from the party that Green Tongue offered them. The fire bloomed like the sun before it had been blinded by the metal ship. The villagers remembered the way Green Tongue lectured them about the fire, blue goddess’ dress and the power of the grills. They sat on the golden sand, watching drunken bodies convulse and soften, sizzling and crunchy.

Villagers put Green Tongue on top of the flesh pile. Black Beard was too big; he was the foundation of the body's tower. Pale Face wasn't drunk, and he didn’t sleep among the dead meat. He stood on the boat and witnessed the glorious outdoor party turning into a massive grave after the smoke thinned. His frail chest heaved in the smoke of his kind. He hid deep inside the metal boat cabin. But no one bothered seeking him out. He was just a forgotten piece of a faded islet.

*

The ending part of this story was told by an old beggar with the bleached skin, paddling his sampan to beg across the rivers of the endless water.

"The people, after carousing themselves with the sizzling dead meat of new settlers, fell asleep right at the party ground with their monumental feast. At that moment, the dyke busted. Water roared and a giant catfish surged from the depth, launching its steelhead into the soft bank of the islet. Its tail kicked the metal ship cabin. Iron frames and panels rained onto the village's entrance. Water swept away all the sleepy and stuffed villagers into its bottomless river. The giant catfish had the opaque irises of the blind woman.”

The beggar shook when telling this part of the story. He recalled how he couldn't see his reflection in the catfish’s eye. Its mouth chewed the metal cabin; its glittering tail flipped the ship over. He flew offboard. He landed on the fish's back fins, where the thin and shiny bones punctured his eyes. He heard the fish croak until the river quieted down into a sleepy flow. In his eternal darkness, he couldn’t picture the new world that he and his kinds slaughtered.

Hung Viet Nguyen - Sacred Landscape VI #1 (2022), oil on canvas, 48 inches x 60 inches

Image description: The painting depicts a night-time landscape featuring mountains, hills, a waterfall, and a canyon. Sharp, white shapes in the background resemble icy mountaintops. A steep, triangular shape towering in the middle of the painting resembles a tall mountain. Its left side is a waterfall. It is surrounded by rock-like shapes rendered in shades of green and brown. In the foreground, colorful fields of yellow and blue, dotted with whimsical plants, are painted on top of cliffs overlooking water rendered in blue swirls and spirals. Minuscule human figures are painted on the cliffs. The human figures are in pairs.

Khải Đơn is a Vietnamese writer, seeking conversations and examining the meaning of living with nature in the constant conflict with modern development. Her debut poetry collection, "Drowning Dragon Slips by Burning Plains," is a fable of loss in the soil and water of the Mekong River.

*

Artist Hung Viet Nguyen was born in Saigon, Vietnam, in 1957. He studied Biology at Science University, then transitioned to working as a graphic artist after settling in the U.S. in 1982. He developed his artistry skills independently, studying many traditional Eastern and Western forms, media, and techniques. Nguyen’s compelling, labor-intensive investigations of oil paint reveal a methodical mastery of textures. While portions of Nguyen’s work suggest the influence of many traditional art forms, including woodblock prints, East Asian scroll paintings, ceramic art, mosaic, and stained glass, his ultimate expression asserts a contemporary pedigree.

With three poems for Eco-, Dorian Merina explores when homecoming becomes possible for the displaced.