Gatekeeping Eden

By Jess Jacutan

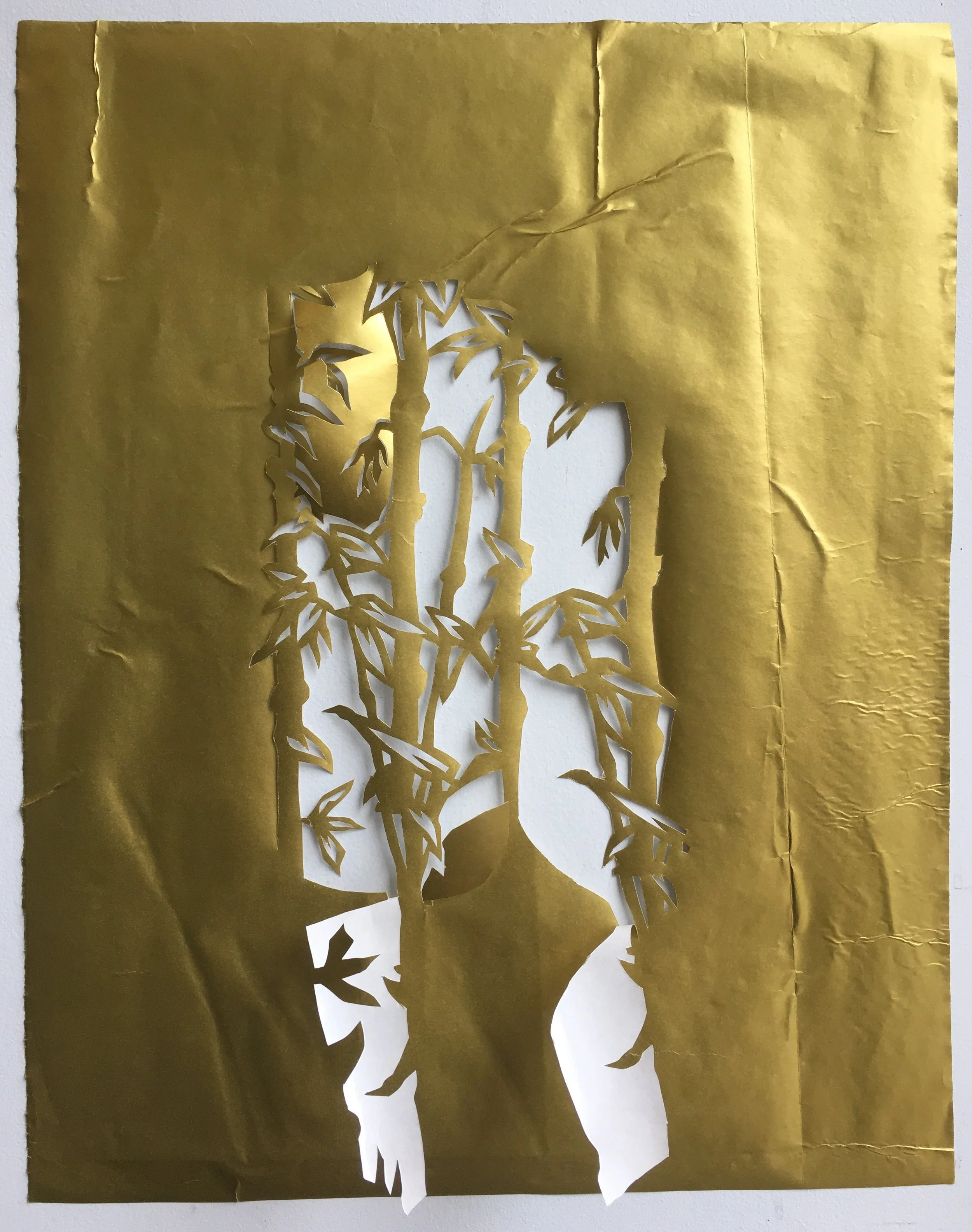

Geela Garcia - Zero Waste (2022), Photograph.

Image description: On the left side of the photograph, a figure is captured in mid-air, jumping into a body of turquoise-blue water, against a lush, natural backdrop of waterfalls and tropical plants. Groups of people are vaguely discernible in the background of the picture.

Siquijor is not my hometown, nor my current residence. Those titles belong to Naga City and Metro Manila respectively. Yet every year, for exactly a week, I call Siquijor my home.

An hour’s boat ride from Dumaguete City, Siquijor is known by many Filipinos and foreigners alike as the Philippines' healing island. Spanning roughly three hundred square kilometers, it remains largely untouched by the overdevelopment seen in most of its Central Visayas neighbors. It’s a place where one can still be startled by a ten-inch tuko lounging lazily on a hotel balcony, and where the tourist attractions sound positively Ghibliesque—a 400-year-old balete tree, a three-tiered turquoise waterfall. Even its Spanish name, Isla Del Fuego, is positively enchanting: the island of fire, after the fireflies that used to swarm over the island's molave trees at night.

Sit quietly beneath the canopy of trees and the first thing you’ll notice is the birds—pecking at fruiting branches, dive-bombing chlorinated pools, flashing yellow and green as they zoom past. Some even approach sunbathers on the sand with complete trust. Birdsong is only one of the natural joys that calls me back to Siquijor year after year—like a gypsy drawn to Macondo in One Hundred Years of Solitude. And I worry that just like Gabriel García Márquez’s ill-fated town, Siquijor’s appeal will eventually fade, transformed by tourism and gentrification, until what makes it home is no longer recognizable.

*

Change, like the tides, does not ask for permission. Siquijor’s evolution year after year is undeniable—from more nightlife spots winking late downtown to new eateries serving dishes beyond the local law-uy. Seven boat companies now serve the island, from just three regular operators in 2020. Dirt roads are slowly but surely being paved over for easier access to Siquijor’s numerous waterfalls, caves, and rivers. With the exception of the pandemic lockdowns in 2020 and 2021, tourist arrivals have climbed steadily since 2017. Last year, as reported by the Philippine National Economic and Development Authority, Siquijor recorded its highest numbers yet —241,529 visitors, a 43% increase from 2023.

Much of this growth has been enabled by improved infrastructure. Recent upgrades to Siquijor’s ports have increased their capacity to serve multiple vessels simultaneously. Even Siquijor’s sole airport, which has previously only served private aircraft, is being modernized to accommodate commercial flights. At the same time, the arrival of Starlink’s satellite internet system has made the island more connected and increasingly attractive to digital nomads, with more cafes and accommodations marketing themselves as remote work–friendly.

Yet at street level, much feels the same. Locals and fair-haired tourists zip past on motorcycles and tricycles. They are the only vehicles nimble enough for Siquijor’s narrow, often mountainous interior roads, keeping traffic nonexistent despite the growing number of people on the island.

By late afternoon, karaoke echoes through neighborhoods—the locals’ way of affirming their presence within the landscape. As the sun sets, families gather along the shore to glean shellfish. Fishermen wade into the sea at dusk, lanterns and nets in tow, while the rest of Siquijor settles into supper.

For years, Siquijor’s rugged shores and limited accessibility have kept it off the beaten track. Ferries are slower, the mobile signal unreliable, and the island’s beaches—though beautiful—are not always conducive to swimming. Most of the island’s surrounding waters are too shallow, too rocky, or peppered with sea urchins and thick beds of kelp.

The more accessible beaches, like Paliton and Salagdoong, are open to the public year-round. Many others, however, are slowly becoming private—sold to corporations and closed to locals who once had the sea as their backyard. One example of privatized paradise is Kagusuan Beach, which has been fenced off since 2017. On some days, the people guarding the area would allow tourists in for a small fee; on others, it’s entirely shut. The only constant is the sign by the entrance, stating that the beach is the private property of Federated Realty Corporation.

For the most part, the island’s rising popularity as a tourist destination is welcomed. Tourism brings commerce, jobs, and social diversity. Young people, in particular, are thriving—becoming more metropolitan, sharpening their English, expanding their horizons. Aside from frequent exposure to international tourists, a long-standing reliance on overseas work has made Filipinos adept at being social chameleons. They easily and determinedly take to the English language, because it is a gateway—to a better-paying job abroad, a foreign partner, and a future that may or may not unfold in their own country.

In Siquijor, speaking English also means getting to play middleman to expats looking to buy land and set up businesses. Most of these businesses cater not to locals but to foreign tourists—driving up coastal property values and pricing out residents who have been living here for generations. Restaurants boasting Italian, Spanish, and Singaporean cuisines have become the new centerpieces of Siquijor’s main streets and beachfronts, sprouting up along formerly quiet stretches once lined with trees and modest unpainted homes. Their prices are eye-watering to the local fishermen, tricycle drivers, and hotel workers.

Despite their willingness to spend at foreign-run establishments, some tourists are quick to cry ‘scam!’ when it comes to paying the locals their due. Tips are begrudged for porters hauling luggage, or tricycle drivers charging a few pesos more for uphill rides. Local-owned inns are scrutinized for their pricing even as resorts charge tenfold. Tourists demand paradise, yet hesitate to invest in the very people who hold back its fall.

*

I romanticize many things about Siquijor, the way one makes excuses for an errant lover. I romanticize its brownouts: an issue occurring at least once a week, and more during the summer and storm seasons. The sheer electric brilliance of lightning dancing over the sea can only be fully appreciated in a world devoid of artificial light—a split-second camera flash that illuminates Dumaguete and Cebu in the distance, reminding me that we are not alone in this world.

But one can only wax poetic about the absence of a necessity when it isn’t a daily reality. The truth is, there simply isn’t enough power for the island. Ten years here and the reason is the same. Not enough generators to provide electricity, someone commented on a Facebook forum for Siquijor residents. By now, you should know to seek your own solutions. Buy solar systems. Buy generators.

And then, there is the lack of water—something far harder to romanticize. After heavy rains, tap water in barangays like Maite and Tubod runs brown. Elsewhere, shortages are common, forcing many to build water tanks or rely on deep wells—a precarious gamble, with groundwater prone to fecal contamination and the proliferation of coliform bacteria.

Waste, too, is a growing issue. Siquijor’s local government is doing their best through zero-waste ordinances, but policies are only as strong as their enforcement. Without a landfill, municipalities turn to temporary dumpsites known as residual containment areas (RCAs). These raw and open sites are only stopgap solutions, potentially leaking leachate into the land and surface waters if left unmanaged for too long. The recent opening of a waste treatment facility is a step in the right direction for dealing with septage. But when it comes to solid waste like plastics and other non-biodegradable materials, the island is still searching for long-term answers.

Tourism magnifies these struggles while creating new ones. Siquijor has its own farming and fishing industry, but it still relies on Negros and Cebu for the rest of its food supply. As more tourists arrive, food prices shift, widening the gap between demand and affordability. What was once plentiful—fish, meat, tubers—becomes scarce. Not because the land no longer provides, but because what it yields is increasingly being priced out of the locals’ reach.

Beneath the surface, the reefs are changing too. Beyond the plastics and chemicals generated by its supply chain operations, the tourism industry also leaves its mark on Siquijor’s coastal systems—through careless snorkeling tours, unchecked contact with marine life, and the runoff of sunscreen and boat fuel. Siquijor’s government may be proactive, offering programs and scholarships to align local business practices with global environmental standards—but even the best-trained marine guides sometimes hesitate to comply. When they see tourists touching corals for photo opportunities, or dragging flippers through delicate reef beds, some will say nothing. Because the calculus is simple. If scolded, they might stop coming.

*

Geela Garcia - Zero Waste (2022), Photograph.

Image description: The photograph depicts a natural landscape. In the foreground, a clear body of water is surrounded by rocky terrain. The background features a dense area of lush, green trees.

All efforts to promote sustainability face backlash, especially when they cross livelihoods. Siquijor is no exception.

In 2017, the provincial government passed an ordinance banning Styrofoam and regulating single-use plastics. The pushback was swift and expected, particularly from market vendors and carinderias that rely on cheap, disposable packaging to keep costs low and their businesses afloat. Over time, incremental shifts have emerged: the disappearance of small plastic beverage bottles in sari-sari stores, the quiet introduction of reusable plates at night markets. These changes feel like progress—but plastic bags still persist, and carinderias continue to offer them when prompted. Refusing might mean losing a sale, and a sale is survival.

In San Juan, the island’s busiest tourist hub, the government recently imposed a ban on fishing, diving, and snorkeling for three days following every new moon. The rule is meant to protect vulnerable fish species during their spawning season, allowing them time to breed and replenish their population. On paper, it is foresight. In practice, it is a test of patience. Tourists who come solely to dive and snorkel find themselves frustrated, their short stays coinciding with closed waters. Fishermen face an even greater burden—three days without a catch means three days without income.

*

If there is one form of preservation that most Siquijodnons embrace without question, it is the safeguarding of their heritage.

For centuries, Siquijor was misrepresented as a land of malevolent aswang and barang, a reputation whispered into existence by a group of tourists-turned-immigrants: the Spanish friars of the 16th century. They were likely threatened by the indigenous healers, mystic believers, and animistic rituals that resisted the Church’s authority. Today, rather than denying its mysticism, Siquijor has reclaimed it. The title of The Healing Island encompasses all that Siquijor has to offer: its unspoiled nature, its accommodating people, its local shamans and their ethnobotanical remedies that protect rather than harm.

Healing is everywhere in Siquijor, woven into its identity. Like the roots of its ancient balete tree, which thread and tangle throughout the earth, healing spreads weblike from the roadside stalls with their bottles of potions all the way to the mountains where healers have been practicing their rituals for decades. These healers are known by many names. The mangangalap forage for raw materials to transform into potions. The mananambal heal through a fusion of herbal medicine and spiritual rites. The manghihilot practice their craft through touch, massaging the body to realign it with its spirit.

Every Holy Week, all of these practitioners converge on the slopes of Mount Bandilaan for the Folk Healing Festival—a gathering that attracts hundreds of healers, locals, and visitors eager to witness or partake. As a protected nature reserve and Siquijor’s highest peak, the mountain is sacred to locals not only for its biodiversity, but also for the spirits said to dwell within its forests. Here, potions are brewed, rituals performed, and the boundary between the seen and unseen thins.

Even on regular Sundays, the line between tradition and modernity blurs. Makeshift Catholic altars bloom along sidewalks—wooden stools and plastic chairs transformed into shrines, bearing small crucifixes, statues of the Santo Niño, or framed images of the Sacred Heart of Jesus. Candles flicker among rosaries, wild-picked flowers, or wreaths of sampaguita, gently wafting grey smoke in the air. The afternoons fall into quiet reverence until commerce picks up again around dinner.

Out of respect for these local traditions and the government’s larger cultural celebrations, nightlife hubs in municipalities like San Juan are required to secure permits for evening events. But some businesses, often foreign-owned, miss the memo. During Holy Week, parties pop up in municipalities with no ordinances against noise, catering to tourists expecting revelry, rather than honoring a community’s observance of solemnity.

*

The irony of gatekeeping tourists as a tourist myself is not lost on me. My investment in Siquijor’s future is admittedly selfish, born not only from admiration, but the longing to preserve a place I might one day call home. I recognize the contradictions of my desire. I love Siquijor from a distance, shielded from its shortcomings by the brevity of my stays. If I were to settle here, I too would become part of the strain on its limited resources. And like so many before me, I would find myself rooting for tourism—not as an outsider critical of its effects, but as a resident hoping it might solve the problems it amplifies.

Tourism is often framed as an individual pursuit, a transaction between consumer and provider. We tend to see its power as one-directional—where tourists from economically-privileged countries hold sway over less-advantaged communities, reinforcing existing inequalities and commodifying cultures. Mass tourism, in particular, has been accused of taking more than it gives.

But power is not so simple. French historian and philosopher Michel Foucault challenges the idea that power is held solely by a central authority or wielded through overt domination. In The History of Sexuality, Volume I, Foucault writes: "Power is everywhere; not because it embraces everything, but because it comes from everywhere.” To him, power is diffuse, relational, and in flux—constantly being negotiated, rather than being purely repressive. Power does not belong to a leader, a government, or an institution alone. It is embedded between every social interaction, existing in gestures, norms, language, and the things people allow and ignore amongst each other.

Within this framework, the perception of tourists as imperialist consumers and locals as passive recipients falls apart. Power moves in both directions, governing the way tourists behave in unfamiliar places and the way that locals frame their culture for external consumption. Tourism is not just a taking, but a dynamic, reciprocal exchange—one where both tourists and locals exert agency, shaping each other’s experiences, expectations, and futures.

Siquijodnons, then, are not, and should not be considered, powerless in this exchange. They can be proactive participants, not just as hosts, but as architects of a kind of tourism that actually serves them. In branding Siquijor as The Healing Island, local governance exercised its ability to resist exploitative practices. It turned a colonial-era curse into an asset, reframing Siquijor’s folk healers and herbalists not as remnants of a fearful past, but as keepers of wisdom worth honoring. The island’s policies on nightlife and cultural events are another example: an assertion that commerce will not dictate the island’s rhythm, that local traditions will not be subsumed by unchecked expansion.

When well-intentioned regulations spark tension between sustainability goals and everyday realities, a deeper negotiation of power is needed. For tourists, Siquijor’s environmental regulations are a fleeting inconvenience. But for locals, they are a question of survival. To balance ecological preservation with economic security, policies must recognize and respect another kind of nature: the human instinct to endure, to make a living, to keep one’s home in the world.

If tourism is to sustain Siquijor without consuming it, residents must not be left behind. Tourism revenue must flow directly into local hands. This means enforcing local ownership quotas for tourism businesses, ensuring that profits remain within the community. It means training local fisherfolk and boatmen as conservation educators, reef monitors, and marine park rangers, redefining their role in marine tourism and conservation, so they are not solely dependent on extractive livelihoods. To ease the transition for workers affected by seasonal bans and ecological closures, the local government can establish compensation schemes or temporary income programs—funded by tourism revenues and environmental grants, which can also be used for skills training and gear subsidies.

Local governance also has the power to control the impact of tourists-turned-immigrants, ensuring that they do not strain the island’s already fragile resources. Thoughtful zoning and siting regulations can prevent overdevelopment in communities facing water and power shortages. Business permits can be prioritized for applicants who demonstrate self-sufficiency in energy or food production. Special training and incentives could also be introduced for permaculture farms and other self-sufficient food producers, expanding local food production and creating jobs that do not rely solely on tourism. More long-term migration can attract the very minds capable of solving the problems tourism creates; it should be preemptively shaped through policies that attract migrants skilled in sustainable development, regenerative food production, and community-driven conservation.

Short-term visitors too should bear the responsibility of protecting the place they come to admire. Tourists can be encouraged to stay at locally-owned eco-lodges, traditional houses, or small-scale accommodations—much like the policies practiced in Costa Rica and Palau. A mandatory eco-tax or a formal sustainability pledge could help ensure that they understand and play their role: not as passive observers, but as temporary custodians of fragile ecosystems and a living culture. The Palau Pledge requires visitors to sign a declaration promising to respect the country’s ecological and cultural heritage. The Icelandic Pledge goes one step further by reminding visitors not to engage in dangerous photo opportunities and off-road behavior. Though largely symbolic and still understudied in their long-term effects, such pledges carry weight in subtler ways: by guiding tourist conduct and setting the tone for how to behave in a place with care.

Most tourists do not seek to cause harm. However, they may lack the context needed to behave responsibly in unfamiliar environments. For Siquijor, a pledge is a low-effort, zero-cost way to inform visitors of the local sustainability ordinances, such as the ban on single-use plastics. It also sets tourists’ expectations around potential activity restrictions due to coastal closures—defusing tensions before they arise, and sparing locals from misplaced frustration that could threaten both their dignity and livelihood.

Tourism, ultimately, is a site of contested power: one where control is never absolute, where influence is constantly shifting between visitor and host. Left unchecked, it can erode Siquijor—by turning homes into backdrops, traditions into performances, and ecosystems into casualties. But it does not have to.

The challenge, for me and fellow tourists, is not to simply visit and consume a location’s traditions, resources, and beauty indiscriminately—it is to exist responsibly within a place. To truly love a place is to ensure it remains home for its original residents, human and nonhuman. Sustainability cannot be a hollow promise, nor a top-down policy that alienates the very people it seeks to protect. It must be woven into the rhythm of all life.

In the case of Siquijor, it means holding fast to its mysticism and traditions, safeguarding its biodiversity, and ensuring that its people—not passing visitors—reap the benefits of its prosperity. If approached with intention, tourism can be more than a balancing act between preservation and progress. It can become a force that fosters life, rather than eroding it. But to do so, tourism must be shaped: not by those who come and go, but by those who have always called this island home.

Geela Garcia - Zero Waste (2022), Photograph.

Image description: The photograph depicts a large, dense mass of plastic waste, consisting mainly of plastic bottles, cans, and other packaging. The waste has entirely covered the surface below it. The bottles bear recognizable, consumer brand names and logos.

Note: The photos first appeared in an article in the South China Morning Post.

Jess Jacutan is a Filipino writer based in Manila. She holds a BA in Communication Arts from Ateneo de Naga University. While her main focus is business and financial writing, she occasionally explores creative nonfiction and op-eds. Her work has appeared in both local and international publications, including World Economic Forum and The Philippine Daily Inquirer.

*

Geela Garcia is a Filipino freelance photographer and multimedia journalist based in Manila, Philippines. Her photographic work, which documents stories of women, food sovereignty, and the environment, aims to write history from the experience of its makers.

“[Doubt] contains within it a seed of desire, for one can only want what one does not immediately possess.” SUSPECT editor-in-chief Sharmini Aphrodite reviews Jonathan Chan’s bright sorrow.