Migrant Tales

“this migrant soul enriches this earth”: Encounters with Migrant Bengali Poetry in Singapore

By Richard Angus Whitehead

Introduction

In the final section of Daryl Lim’s very recent poem ‘Running by the Kallang’ we encounter a sustained, intimate, yet troublingly distanced portrait of migrant workers in Singapore.

In their lungis, they commune in circles

bisected by the footpath and sing,

white teeth lightening the night

and homesick hearts, the newest seekers of hope

on these banks. I wind my rapid way around them:

it seems our two worlds will never meet.

Yet as I slowed to finally disperse

the lactic from my legs, one of them met

my eyes as he laughed – and waved, seeming to wish

that I could share the joke, could suddenly

be gifted with the Indic tongues. The miracle

undelivered, and so lacking the syllables,

I made do with a smile and raised hand.

One wonders when migrant workers first appear in Singapore writing? We can easily go back to 2013 and Theophilus Kwek’s poems ‘Little India’, and ‘Chinese Workers on the Evening Train’ in his first collection They Speak Only their Mother Tongue, although the latter poem has possibly more to say about uneasy contemporary Singaporean attitudes to migrant workers, and foreigners in general, than migrants themselves. Alvin Pang channels and privileges migrant worker’s voices in his poem ‘Made of Gold’ (c 2000):

This all I got after working a

year. If only someone told

me the walls of Tekka

are not made of gold.

Significantly further back, in the late 1980s, Filipina domestic maids recounted their experiences which were collected in Loo Bee Geok’s ‘I am a Filipino Maid’. Helmeted construction workers, a detail from Lee Boon Wang’s nation-affirming painting ‘Workers in a Shipyard’, dominate the cover of Robert Yeo’s Singapore Short Stories. Even further back, in the late 1950s, former mui sai Janet Lim published her captivity narrative Sold for Silver. But there surely must be, or at least have been, extant accounts of coolies, mandores, Pakistani sarabat stall owners (as we encounter in Gregory Nalpon’s ‘The Rose and the Silver Key’) and others, taking us much further back, which require energetic historicist attempts at unearthing. Such evidence earthed and unearthed reminds us that Singapore has had migrant workers for a very long time. Is postcolonial Singapore anything if not a nation of descendants of migrant workers? Reading Lim’s poem, reflecting upon the institutionalized marginalization of those actually creating twenty-first century Singapore, one wonders when migrant workers in Singapore stopped being ‘us’, family, and became the foreigner, the one we could other.

At least one ‘pioneer’ Singapore poem of key importance in the context of what I want to talk about in this paper—Anglophone translations of Bangladeshi migrant poetry currently being created and disseminated in Singapore—is Wong May’s ‘East Bengal’, which engages with Bangladesh’s birth as recently as the early seventies out of genuine, unequivocal major crisis, a most bloody, tragic war.

[children] are ancient

like milk

they don't keep

they are wise

like dried fish

they lie by the roadside

After Cholera

and War

they expect to see God

The rooted patriotism, the organic nationalism of Bangladeshi migrant poets, workers from ‘the land of the language of Bangla’ may help us to begin to attain a deeper, more nuanced understanding of the life experiences of Bangladeshi worker-poets in Singapore, and the articulation of those experiences, including feelings of homesickness for the mother country, as well as alienation from ‘normal’ mainstream life in Singapore present in their poetry.

In the first half of this paper, I will discuss a recently published collection of translated Bengali migrant worker poems composed in Singapore, Migrant Tales (2016/17). But also, midway through, I want to illustrate the not wholly ideal state of affairs concerning translating poems from Bengali into English in Singapore in the mid-2010s by comparing two translations of a poem by currently-feted migrant poet Md Mukul Hossine, whose writing has been proactively promoted and framed by local charitable-medical organization, HealthServe, as well as by Singapore’s literary establishment over the last twelve months or so.

In the second half of the paper, I will discuss the poetry of a currently slightly less media-exposed, but equally talented migrant writer, MD Sharif, principally through a discussion of his poem ‘Little India Riot: Velu and a History’ which engages retrospectively, poignantly with the significance of the 2013 Little India riot in Singapore, in the persistently foregrounded light of the riot’s spark, the senseless death of Tamil construction worker Sakthivel Kumaravelu.

Migrant Tales

When I first read in November 2016 that the publication of Migrant Tales: An Anthology of Poems by Migrant Bengali Poets in Singapore edited by Zakir Hossain Khokan & Monir Ahmod, translated by Debrabota Basu (Dhaka: Morshed alam readoy, 2017) was imminent, I was excited. While Ethos Books have been recent pioneers in publishing a collection of translations of poems by Muhammad Mukul Hossine, I, Migrant (2016), I had been hoping for some time to read a significantly wider, more representative collection of migrant laboring poets’ work, reflecting a broader range of migrant poet experience, as evidenced during the last three years of the migrant poetry competition in Singapore, as well as a less stylized, more authentic, ‘Bengali-centric’ rendering of the voice and experience of those poets into English. Migrant Tales, some frustratingly avoidable typos and grammatical errors aside, certainly features high-quality poetry, and gestures to the authentic richness and range of Bengali migrant poetry in these twenty-five poems by seventeen new poets. While this brotherhood of poets apparently collectively published their book in Dhaka (then imported it here and sold it for half the average price of a book of poetry in Singapore), the collection continues to be regularly celebrated through a number of ongoing readings at bookshops and other venues in Singapore since its arrival and distribution here in early December 2016. Hopefully this independent and proactive collective of Bangladeshi migrant poets will continue to find support and a welcome among Singaporeans while independently developing and disseminating their own distinctive poetic forms and voices. On their own initiative, Bengali migrant poets in Singapore appear to have rapidly created a more liberated William Blake-like milieu in which they translate, disseminate and promote their work relatively independently of the milieu of Singaporean literary publication, including the National Arts Council and local presses. But while these poets are for now currently celebrated and lauded at readings by the local literary community and wider public, for their initiative as well as their work, and perhaps plight, I hope that these intriguing poets, even in the imperfect English translations we currently encounter them in, receive close and reflective scrutiny, as well as a placing in Singapore’s historico-literary canon. MD Sharif’s ‘Little India Riot: Velu and History’, for instance, remains the most sustained, considered poetic response to the 2013 Little India riots in contrast to actual Singaporean poets’ curious near-silence on this event. At the same time it is hoped that the Singaporean poetry-reading community will move beyond reactions of excitement at novelty and sympathy regarding migrant poetry and begin to judiciously appreciate the full import and context of works refracted through fascinating literary traditions so different, far longer, and at least as rich as Singapore’s own.

Since my David Erdman-inflected William Blake-induced early days of postgraduate training I remain a dyed-in-the-wool historicist, so as well as focusing upon prosody, linguistics, intuitive fall-off-my-chair responses to this just published East-Bengali poetry in translation, I am intrigued by those specific moments in Migrant Tales where Singapore, and labor in Singapore, is unequivocally engaged with by living breathing migrant poets in a specific place at a specific moment in time, say, the concluding sections of MRT tunnels in the mid-2010s. These moments are present but not plentiful in this collection. Nor should they necessarily be. Migrant poets, as the collection demonstrates, have a whole host of other subjects to write about. Still, I was intrigued as to why the activities that perforce take up so much of migrant workers’ time, of which most of us know so little, are so irregularly touched upon. Could it be because Singapore construction sites, canteens, and approximately twelve-to-a-room dormitories (the circumscribed Singaporean spaces which workers are obliged, constrained, to inhabit—as recorded in Mahbub Hasan Dipu’s stark repetition of his hyper-specific address in his poem ‘In Exile’, ‘[Block] 31, Street 2, Sungei Kadut’) are not the stuff that migrant poetry is primarily made of? Alternatively, perhaps these poets have consciously or unconsciously adopted a politic strategy (that perhaps we all adopt in this place, this climate infected with something vaguely akin to fear) by editing and policing themselves, writing poetry here in which anything concerning the more controversial, morally reprehensible aspects of their treatment as exploited migrant labour without which uber-capitalist Singapore would not be where it is today, are shied away from, not confidently engaged with in detail? Or, as may have been the case with Mukul Hossine in Me Migrant, are poets edited and translated for local consumption in Singapore’s preconceived image of migrant workers, their more complex, ambitious, controversial works not deemed suitable, or saleable for publication in Singapore? But one wonders, does a local readership really desire unequivocally ‘safe’ migrant poems, laments of homesickness, love songs, with the occasional obsequious subaltern paean to the late Lee Kuan Yew or Singapore at fifty? Surely a Singaporean readership could also appreciate, handle Bangladeshi worker’s literary descriptions of, and responses to, questionable conditions, hard work for long hours for little pay (by Singaporean standards), or the uniquely troubling phenomenon that was the 2013 Little India Riot. As I hope to argue, the moments when migrant poets do engage with their work and lives here, the stuff which the ‘Editorial Note’ of Me Migrant seems to dismiss as unpoetic everyday mundanities, become rather, to this writer at least, potentially impactful, arresting, illuminating, crucially important.

The cover of Migrant Tales depicts successive white clouds in a bright blue sky, framed in unvarnished light wood, literally skylights, which may perhaps have been inspired by the last lines of twenty-nine-year-old construction worker Sikder Muhammad Sumon's lyrical 'If you remember',

If you think of me

in a silent moonlit night,

unlock your window, and

I would become your sky.

As intriguing is the title of the collection: Migrant Tales [my emphasis]. These poems certainly convey a rich variety of tales, and, while not tale-telling, they surely encourage Singaporean readers perhaps for the first time to sustainedly reflect upon the lives and conditions perforce endured by those, from another land, with a possibly closer relationship to nature than the average socially engineered twenty-first century Singaporean’s, but then ironically tasked to physically rip up, hollow out, and remake this once soft green, now ever more hard grey country. But an anonymous poet surely explains this better in the introductory lines:

Textures of migrant’s words,

entwinements of their sentences

are outlandish, like their lives.

and, exiled in the city of dreams,

lost in its busy cacophony,

let poetry tell the migrant tales.

The lines perhaps suggest that there is a tellingly revelatory quality to these odd, “outlandish” (through the situation here imposed upon them) migrant worker poets’ equally outlandish poems: their content and form born of not only hard labour and long hours but estrangement (from within their new ‘home’ as well as from their true, original home) and loneliness in this fast-moving, ever more crowded, unstoppable city-state. What are the effects, one wonders, on the migrant writer’s sensibility? How does a writer mortally immersed in Tagore, Kazi Nazrul, Jibanananda Das, and centuries of poetry and song, respond to this materially over-developed, culturally arrested orphan island?

Muhammad Sharif Uddin’s ‘Exiled Heart’ includes the line ‘let me tell my tale’ (43) in a poem which begins by asking,

Who does care about the pain of migrants

working under the soil of the city of forever spring?

‘City of Dreams’ as well as ‘City of Eternal Spring’ being polysemous and possibly not unironic euphemisms for the unseasonable land, many Bengali workers are hired to honeycomb underground, prefab above ground until at least 2030 when the Mass Rapid Transit (MRT) project is finally completed. The collection’s simple dedication ‘To all/ who left home’ gestures to a theme visited more than once in the ensuing poems that Singapore (even after the decades some of the poets here have spent in Singapore) is not, and perhaps never will be, home. Even more worrisome, can the beloved mother Bangladesh, literally land of the Bangla language, after so much time forgone in Singapore, ever be the same again, ever be again fully home?

Migrant Tales features a short preface by Alvin Pang, a Singaporean poet who has played an enduring role in the three annual migrant poetry competitions that have been held to date. (His role in the first migrant poetry competition is immortalized in George Szirtes’ recent NTU chapbook Singapore Journal (Ethos, 2015)). In his preface, as well as reminding us of how little Singaporeans comprehend of migrants’ lives, Pang also reminds us that poetry has not always been the often self-consciously intellectual-hip hobby of not un-heeled youth we increasingly encounter on this small island, but an age-old global phenomenon of community, speaking and singing "truth to power the world over for millennia […] fed from and feeding the full range of human experience." Thus Bengali migrant poets hailing from a nation culturally, if not financially, richer in traditions than Singapore are finally empowered, through Migrant Tales and accompanying readings, to share their poems with Singaporeans, thereby potentially informing and enriching Singapore’s literary scene and well beyond. These poems speak pertinently of migratory experience of exile, loneliness and isolation, but also of the minute particulars of the nature of their work here, fraught with incidences which all must concede are unfair. The poems also explore memory, beauty, family, love, home, and homesickness dealt with by conjuring up and recreating the quotidian details of home through imagination, through poetry. Key words revisited in the poems include home, grief, tea stall, canteen, evening, morning, rain, water, women, moon. Through content and form, Singaporean readers are bought back through the migrant poet’s homesickness to the intimate exteriors and interiors of Bangladesh. While Singapore is contained in the phrases used by migrant poets: ‘City of dreams’, ‘City of Eternal Spring’, ‘home’ in Bangladesh is recollected through unique minute particulars: Padma (Lotus), kadam (flower, tree), bhatiyah (traditional folk songs of the river country), bakul (flower), my golden Bengal (national anthem), hilsa (the best and most expensive fish), jan (love/ life), payes (keer), kochu (root vegetable with large heart-shaped leaf), shimul (flower), baulsongs (religious sufi songs). Indeed, could these poems in a sense be seen as Sufi songs sung in safety helmets?

Migrant Tales contains 26 poems printed in their original beautiful Bengali script, face to face, or closely followed by translations into an English often breathtakingly beautiful if at other times grammatically rawer, rougher and wronger than many of us are perhaps used to in published poetry. First, Debrabota Basu, currently a PhD student in engineering at NUS, in his first poem ‘The Lover’s Grief’, expresses homesickness, divorce from origins, and momentary escape through reverie, but too soon the ‘grief’ of ‘hustle’ returns,

When [....] life calls me back to its hustle,

to forget the infinites and to be small,

not to be a bird but to be a human ,

I feel this grief.

As we shall see, the sentiment resonates with Mukul’s poem, ‘Immigrant Dreams’ and one does get a sense, even in translation, of these friendly fellow-poets talking to and echoing one another. Many poems have striking titles, such as editor Zakir Hossain Khokan’s 'Ballad of Kisses', which, for me, at least in translation possesses an almost decadent lyrical feel, reminiscent of Yeats’ beloved Ernest Dowson. The poem ‘Beauty, at times’ by shipyard health, safety and environment supervisor M R Mizan (affectionately known by colleagues and fellow-poets as ‘Paradise’!) communes with the elements, something increasingly challenging to do in Singapore, especially on a construction site. We get admirable love poetry in the form of construction worker and journalist Mohammad AbdusSobur’s ‘Be the Rhythm’, novelist Kausar Ahmad’s ‘Snatch Away my love’, song-and-TV writer Rajib Shil Jibon’s ‘Indestructible You’, and M R Mizan’s ‘my unquenchable thirst’ . But even in these poems, images of iron and steel suggest some gesturing back to their present everyday labour of hard construction. There is also the literally invigorating feel-good poetry of Sharif’s ‘I feel Good’.

Under the full moon sky,

if I listen to a crowd singing

in the rhythm of dhol and ektara,

or a sweet voice chanting

“Amar sonar bangla ami tomay bhalobasi.”

I FEEL GOOD. [23].

Whatever the circumstances, even in Singapore, the powers that be responsible for circumscribing workers’ movements, moments of happiness, access to Little India, seemingly can’t wholly keep the migrant worker’s spirit down. But Sharif’s original Bengali in meaning, in rhythm, conveys a sentiment so much more richly profound than the bland English ‘I feel good’. Sharif, at my original talk at Singapore’s National Institute of Education, upon which this paper is largely based, communicated his frustration that the rhythm-feeling of his poetry has yet to be fully captured in English translation. We await a translation that can bring us closer to this accomplished writer’s original meaning, feeling, and spirit.

The last line of Sharif’s last stanza is the first line from the Bangladeshi national anthem ‘Amar Sonar Bangla’ ("My Golden Bengal"), composed by a friend of W B Yeats’, Rabindranath Tagore: “My golden Bengal, I love you.” Tagore’s image of the speaker as a child in the lap of mother Bangladesh sensitizes us to the connotations of mothers who frequently appear in Migrant tales, not least in Mukul’s poem discussed below. ‘Ma’, mother, clearly represents not merely biological mother but mother Bangladesh from which migrant poets are painfully and sustainedly separated. A softer, perhaps more emotional, organic Patriotism than Singapore’s is something I’d not initially appreciated in these poems—for a country officially six years younger, but in ways that matter, a motherland far more connectedly and organically older than Singapore.

Rajib Shahil Jibon’s ‘Passion of Moonlight Night’ ends in a treasured brief moment of reverie, a sensual communion with a remnant of Singaporean sublime in a local works canteen:

I would love to be here,

in this canteen chair, for the rest of my life

with this melody of frogs,

raindrops on the blades of leaves,

the smell of the wet soil

and, that enchanting moon.

The Singapore moon, like rain, is a constant theme throughout the collection. Monir Ahmod, in ‘Memories’, also explores homesickness and memory while communing with nature. It is the same in Mohosin Akbar's 'Letter' (which seems almost like a metaphysical poem in its conceit) where he writes,

I used to lose myself in the green of this city

holding your words against my heart

Migrant workers perhaps lack accessible and reliable wireless connection, so Mohosin’s yearning for letters (“send me another letter wrapped in the envelope of wind” (37)) is painfully real to him, if striking the privileged uninterruptedly connected Singaporean reader as nostalgic. The poem is reminiscent of lines in Philip Larkin’s abandoned 1953 poem,

I know, none better

The eyelessness of days without a letter

Age and time, as well as migration, leads to a kind of exile from happy youthful memories.

As I mentioned earlier, we are still some way from if not wholly, then acceptably satisfactory translations of Bengali migrant poetry in Singapore. Simply, the majority of translators lack equal proficiency in both Bengali and English language and culture. Compare, for example, Debrabota Basu’s translation of one of Md Mukul Hossine’s poems included in Migrant Tales and titled ‘Immigrant Dreams’, with poet Cyril Wong’s ‘transcreation’ of the same poem in Me Migrant. ‘Transcreation’ is a word unlisted in the Oxford English Dictionary, but from Wong’s ‘Editorial Note’ to ‘Me Migrant’ the word in this context seems to cover not only translating but also ‘rewriting and editing’, in Wong’s words, a poet’s work in the light of repeated meetings with that poet, exposure to his character, and an attempt at mimicking his way of speaking English, at least in the case of the title poem. (While having next to no major issues with Wong’s approach to translation, I do have an issue with the inclusion of 16 pages devoted to the poetic efforts (some in Chinese) of Singaporean medical students working with Healthserve, in Mukul’s slim volume of just 65 pages.) Here is Wong’s translation:

‘Expatriate Dream’

Can I have a cup of tea, mother

Mixed with ginger and a piece of lemon

Stirred to behold the redness of fresh tea leaves

A cup of hot tea

So long since you made me a cup of tea

Is the jar of rice still there

Now nothing waits for me

To receive in every dawn and dusk

Last night I ate happily

Payasa prepared by you

Lying in your lap

I saw the constellations, mother

You laughed at me in my black shirt

At my frizzy hair

Annoyed you told me to fix it

And brought out a 20-taka note

So I could go out

How happy I was

Like I was in heaven till the phone alarm

Rang suddenly

And I am lying across a shelf bed

Unable to hold back tears

Expatriate means dream-drenched agony

To exist without happiness

Everything a dream

I remember you too much, mother

While the Me Migrant translation, produced by one of Singapore’s most celebrated writers, reads initially much more satisfyingly to the ear, and presumably to the Singaporean intellect (but are migrant construction workers “expatriates” in the Singaporean sense?), Migrant Tales’ rougher, less smooth rendering into English brings out the Bangladeshi-inflected homesickness.

‘Immigrant Dreams’

Ma, may I get a cup of tea?

A warm cup of tea

red from the freshness of tea leaves

and assorted with ginger and lemon!

So long Ma, its been so long that you feed me.

Do you still have that jar full of cookies?

Do you still wait for me

every morning and evening?

Last night, I ate the last drop of payes

you sent,

and looked at the moon and the stars

from shelter of your lap.

You smiled and stared at my black shirt,

and carefully combed my hair

You gave me a dollar

to enjoy the fair.

I was so glad, like I am in heaven.

But then the mobile alarm rang

to break my dream, to wake me up

on my hard bunk bed.

Then, I could not stop my tears to run.

Ma,

immigrant life filled with pieces of broken dreams

a life without smile and drenched in melancholy,

that takes me far from you

as I reach closer to your memories.

As we shall see, translator Shivaji Das, assisted sensitively with light, deft touches by local poet Gwee Li Sui seems to offer an illuminating model of Bengali-English translation.

From Mukul’s poem onward, halfway through Migrant Tales, there seems to be a shift from articulations of experiences of love, homesickness, and nostalgia to a more sustained engagement with the experience of migrant life in Singapore. Md Sharif’s poem ‘Exiled Heart’ conveys the sense of a worker doubly ignored and overlooked as he labours physically, metaphysically, in the dark underground, constructing more MRT tunnels. Beginning by confronting the reader with 'Who does care about the pain of migrants...do you?’ 'Exiled Heart’ again alludes to the title of the collection, 'let me tell my tale,/tale of the immigrants from the land of flames'. Sharif brings us one of the most unmediated explorations of the personal toll of construction work in Singapore upon migrant labourers:

I am an immigrant lost

in the loneliness of hot and humid womb of soil.

The touch of solitude

makes my heart weep and howl,

and every moment like an accumulation of eternities.

The passage seems Blakean in its language: the use of “howl”, “eternities”, migrant workers like Orc or Los contending, laboring, suffering deep under the earth by urizenic mandate. In exile, the migrant worker, ever close but unseen by the fellow inhabitants of his adopted place of residence, seems in constant danger of losing any sense of his own identity as day by day he steadily misplaces the memories of home initially grounding him here.

At the same time these subterranean environs have resulted in MD Sharif and other ‘MRT’ migrant poets writing from a unique poetic lens closed to Bangladeshi poets that stayed at home as well as Singapore poets who have rarely descended to the depths of MRT construction sites.

As my existence gets blurred in the darkness of depth,

I can hardly remember that I belong to this earth.

M A Sobur says something similar in his tellingly entitled 'Elegy for Myself',

At times like a man unwilling to see,

Or at times like a coward,

I am escaping silently.

While in Sharif’s poem, agonies are experienced not least at work, in the act of construction, for Debrabota Basu, in his accomplished poem ‘The Lamenting Refugee’, melancholy returns at the time it can be afforded by the ever-busy worker. Sleep is not as it is for Mukul, an idyllic escape.

Had leaving not been so difficult

would there be the urge to return

in every dream, at every night?

The here and now is where "the urban moon hides behind the lofty facade,/amidst the choking void" in a milieu where "creation is an impetus to destruction".

You can't say it much stronger than Mahbub Hasan Dipu in his poignantly titled poem 'In Exile'. Is that his worker dormitory address, or a prison cell number?

Captivated by mockeries,

I am the man

that I did not want to become,

who lives in a prison cell, at-

31, Street 2, Sungei Kadut.

Sungei Kadut is the location of a number of worker’s dormitories where, even in the best dorms, as many as 16 men are cramped into one room, an iron bunk for ten dollars a night, subject to regular inspections from dorm managers, fined from their small salaries for infringements. And again Singapore, through the migrant's lens, juxtaposes a land of impossible achievement (City of Dreams) with its isolated, estranged inhabitant-natives, who aside from having more money and space, may not be much freer than the worker.

I become oblivious

beholding...nests of lonely souls

and towers kissing the sun.

The poet seems simultaneously lost in the streets, and in solitary confinement – Dipu’s last stanza interrogates a milieu of exploitation and marginalization.

I never know

whether dreams would meet reality

in this turbulent exile, far away from home,

neither do I perceive the schism between

residents and immigrants!

Why are immigrant lives exiled?

What do I look for in the streets

of this city of dreams

though I am confined in a cell at-

31, Street 2, Sungei Kadut.

In many poems there is a representation of the moon, a prevailing trope in Bengali poetry, as in Mohar Khan's evocative poem 'Luggage': "I used to be as pale as this untimely moon".

Khan seems to note that although Singapore is finally acknowledging the migrant poets, it is also, as ever, turning a potentially good thing into a touristic, money-making, student leadership project-worthy opportunity.

Now this moon shines in documentaries,

and front page headlines...

Khan represents himself as a warrior, Singapore a battlefield. Magically, "one by one cities rise from my sweat, from my battlefield...".

An experimental poem of Syedur Rahman Liton’s in a poetic form he invented, ‘nucleus poetry’, gesturing again to this band of migrant Bengali poets’ innovativeness, also contains the word "Howl!", echoing Sharif’s use of this word. But Liton’s references to Rampal and Sunderban denote aggressive capitalist and industrial development currently occurring in East and West Bengal, its benefits and losses not merely the preserve of Singapore.

Conversely, although Zahirul Islam’s ‘Come to my city’ rejects, on one level, development in Bangladesh, it progresses into an invitation to those whose cities (like Singapore) no longer have any shade, to come to his own city:

come to my city,

let it be your shelter

stretching thousand new branch.

We should be cautious in our interpretations, or be aware of what is potentially lost or obscured in translation: Ng Yi-Sheng in conversation with the poet was informed that ‘Come to my City’ was not about Singapore at all, but the break-up of the poet’s marriage. Nevertheless, the poem can be read as an invitation to Singaporeans to visit physically, virtually, Zahirul’s city in Bangladesh, not as patronizing evangelists of business and progress, but as open-minded guests, re-appreciating and regaining something long lost, quickly forgotten in Singapore.

Zakir Hossain Khokan in 'Nature' identifies with nature until all seems to collapse into himself:

Like you, at times

when grief pours down on me,

Nothing can ease the pain but

Nature,

an enchanting touch of magician

But while the Singaporean reader is at comparative leisure to enjoy what's currently left of nature in Singapore, the migrant labourer poet is compelled to 'immerse myself in noise of gigantic machines'. And we seem to be back in the world of Sharif’s ‘Exiled Heart’. Nature for Zakir is now 'soil soaked in/ sweat of craftsmanship' that river-like 'streams down every moment/ through every inch of my skin. 'Again we return to the saddening paradox—the feeling, nature-revering poet is also compelled to be the actual destroyer at a local employer’s imperative. Tea breaks 'shorter than a glimpse', poetry books hopefully bring peace. But, poignantly, the poem—and the collection—ends on a very positive image of a newer generation:

Still at times,

when grief pours down on fatigue-torn me,

in roads and in MRTs

I behold the faces of the infants,

free and pure as nature would be.

Zakir gains solace, places faith, and renews hope in the as yet unspoiled innocence of Singapore’s newest generation.

Muhammad Sharif Uddin: engaging with the 2013 riot in Little India

On the evening of 8th December 2013 at Race Course Road in Little India, Sakthivel Kumarvelu, a Tamil construction worker was fatally run over by the bus he had just been forcibly ejected from. The incident sparked a unique event, an unexpected and overwhelming surge of rage, a full scale riot, involving hundreds of migrant workers, for which local authorities seem not to have been fully prepared. As a consequence, numerous participants were later summarily tried, jailed, caned, and/or repatriated.

MD Sharif’s poem ‘Little India Riot: Velu and a History’ was commissioned for Gwee Li Sui’s historical literature anthology Written Country (2016) two years after the riot. Sharif is described in Gwee’s prefatory remarks to the poem as: ‘a safety supervisor in Singapore who writes from his experience of the time.’ But the poem is some way from reportage. The topic is still comparatively recent, controversial, and aside from Gwee li Sui’s series of haiku, shied away from by local poets. A migrant worker might be in the best position, say as eye-witness, or companion of eye-witnesses, fellow endurer of questionable working conditions, to write a published poem about the riot. But in Singapore’s often expediently sensitive climate, how might a potentially rights-wise vulnerable migrant worker negotiate meaningfully this ideological minefield, this politically embarrassing local-national incident?

Muhammad Sharif Uddin

Indeed the riot has needed to be retrospectively re-framed by state media carefully, ambiguously, awkwardly through privileging a narrative concerning the bravery and efficiency of the responding security forces, and the othering of the rioters, while distancing the narrative from any issue of race. But in such a strategic narrative Sakthivel Kumarvelu, the initial incendiary fatality, rather like the possible deeper causes of the riot, is glossed over. Or, alternatively, as seems to happen to many people regardless of race, or residence status, who die tragically-controversially in Singapore—from National Service casualties, to point block (tall apartment block) suicides following correct-to-the-letter questionings by police or school, to the recent teenage victim of a mall ledge collapse—implicit blame is civilly positioned upon the unanswering dead. The late Kumarvelu therefore, caught between strategy, confusion, embarrassment, currently inhabits the Singapore story as a shadowy unspeakable figure in limbo.

Gwee li Sui’s recent (2017) haiku engagements with the riots question, satirically if also in an elliptical-diffusive fashion, both the Singapore state and the news reports of the riots. For example, on Kumarvelu’s killing and the ensuing riot, Gwee writes,

Tragic accident.

Drunk transient workers in grief

threw veggies, burnt cars.

Or regarding the response of the security forces:

Some people like to

watch the world burn. Some forget

they still have a job.

In the aftermath of the riot, instead of sensitively and systematically investigating and responding to the social issues and injustices underlying the riots, the powers-that-be curbed the rights of workers (and others) to congregate and drink in Little India. Gwee’s response:

Outside, I cannot

Get drunk, after ten-thirty.

So I stagger home.

Sharif’s more sustained, ambitious, and wide-reaching poem does something very different: at a distance of two years plus, Sharif commemorates the unique historical phenomenon of the riot in retrospect by reversing the perspective of the official narrative. The poem, therefore, consistently focuses upon and foregrounds the neglected figure of Sakthivel Kumarvelu, the one fatal casualty of 8 December. The shortening of the victim’s name, to the familiar ‘Velu’ gestures to the unknown worker’s personality, popularity, the affection with which he was regarded by fellow workers; perhaps it also gestures to an unknown, but possibly retrievable ‘bottom up’ thick history of the riots. (A Google image search of ‘Little India Riot’ will yield images of the temporary memorial for Sakthivel Kumarvelu at the site of the accident by fellow-workers, well-wishers and friends.) While the poem reclaims Velu affectionately for public history and space, it also simultaneously mythologizes the worker.

LITTLE INDIA RIOT: VELU AND A HISTORY

Breezy morning, sweet evening

Soon after was history created.

Velu was trapped in a labyrinth of laws,

then a stroke of fate established him.

His youth was wiped out, his breath erased

The city of dreams took away his faith.

The fire of his heart lit the highway

and the road to violence in the city of peace.

Workers wash away the blood of workers

Dreams cry in their undeserved expectations.

The murmurs increase, the footsteps hasten –

police, Gurkhas and the workers.

They were drunken in passion,

Repressed anger unchained in an inspired moment.

The civilized woke up later to say this and that,

but everything stops at night.

Look, Velu lies there in the coffin,

ruthless history buried in earth.

His pulse was beating at dusk

but left the ties of the earth in the evening.

Nothing will stop in this busy city

in the tearful hour of a sweat-drenched worker.

Look, there Velu goes with empty hands

while Development, Progress, Civilisation laughs.

Velu’s dreams was killed in an instant

and History’s spade will hardly unearth it.

Velu lives now in a worker’s heart

and speaks silently for a thousand years.

In this arguably most complex of the migrant poems that Singaporean readers have hitherto been permitted to read in published translation, Sharif while clearly engaged with this public event, this personal tragedy, uses several political-literary strategies of negotiation. The poem is shaped by what Sharif does say and what he does not say. There is a quiet beginning: before a nice day turns into history.

Breezy morning, sweet evening

Soon after was history created.

The poem is framed, regulated, in 14 couplets, two-line sentences, of considerable pressure per square inch. Each couplet could almost stand alone as a poem. No blame for the evening of 8 December is apportioned to any physical individual or group: it is a conjunction of fate, and the location of the ‘City of Dreams’—that phrase again—that changes and frees the regulation-bound Sakthivel Kumarvelu utterly into a now-contested historical figure and force. Contrary to normal expectations, he seems freer, less easy for the authorities to corral, in death. It is not the life but the youth, breath, faith of Sakthivel Kumarvelu that is described as lost, halted as Singaporean progress carries on regardless.

Look, there Velu goes with empty hands

while Development, Progress, Civilisation laughs.

The emotional force of the event plays not only against the form of the poem but also in arresting abstractions: in lines like the sublime “The fire of his heart lit the highway”. It is almost as if Sakthivel Kumarvelu’s young life burns on in the burning flames surrounding overturned responding vehicles. Sakthivel Kumarvelu is the only individualized figure. Sharif in conversation has described how in creating the poem, he, a Bengali Muslim poet imagined himself as the Tamil Hindu Sakthivel Kumarvelu’s brother until he could virtually visualise Velu, an act of determined, sympathetic imagination that again seems reminiscent of the eidetic visionary William Blake communing with visionary heads of the past: William Wallace, Caractacus, Corinna the Theba.

The violence and rage of the initial crowd becomes “Dreams cry in their undeserved expectations”; or more explicitly,

They were drunken in passion,

Repressed anger unchained in an inspired moment.

Police, Gurkhas, and workers are fused in a representation of unregulated passion and unleashed anger. There is an ambiguity in that full-stop before ‘They’ – does “they” then refer to the previously mentioned police, Gurkhas as well, or merely to the workers? In the poem, neither workers nor the security forces are either valorized or indicted. Rather Singaporean (uniformed or lay) and migrant seem bound together by, caught up in, an inclusive history—but a history known or accepted by eye-witnesses, rather than a state media’s mediated delayed retelling to ‘civilised’ Singaporeans who wake to say ‘this and that’. At the beginning of the poem Sakthivel Kumarvelu is ‘established’ in history, but by the end he seems in danger of being written out of it. So Sakthivel Kumarvelu is an Elusive figure in and out of history. Collectively all actors in the initial moments on Racecourse Road on December 8th make for a democratised moment of history – yet they are in danger of dilution, lack of focus, loss as time progresses, as more workers and security forces arrive, as ultimately the following morning Singaporean citizens ‘wake up’ to the news. Such ambiguity is also found in a Singapore represented as an urban space where things stop, but also do not stop. Where progress laughs. ‘Little India Riot: Velu and a History’ is a moving, rich poem, begging questions, saying something about the nature of history – notably, especially as written and rewritten in Singapore’s media and school history and social studies books, yet deft, savvy enough to evade neurotic national censorship.

CONCLUSION

In this paper I have attempted to explore the emotional range, quality, and resonance of a currently emerging migrant-created, Singapore-concerned poetry, fresh and for too long unknown to Singaporean readers. In gesturing to the content and quality of two very different translations of MD Mukul Hossine’s poem ‘Immigrant Dreams’, I have highlighted the urgent need for translators with both a sensitive facility for the English language and an effective immersion in Bengali culture; both the world the Bengali migrant poet has come from as well as the world he is describing.

In exploring MD Sharif’s‘ ‘Little India Riot: Velu and a History’ in its intense, but regulated and deft exploration of a tragic-violent moment in Singapore’s recent history, I hope I have suggested something of the facility and complexity of Bengali Migrant poetry in Singapore, a large proportion of which remains to be translated and published in English, along with many volumes of short-stories, memoirs, and prose. Let us hope it continues to be translated, financed, published, read, and enjoyed, but also studied and discussed carefully, seriously, by readers in Singapore and elsewhere —to everyone’s illumination and advantage.

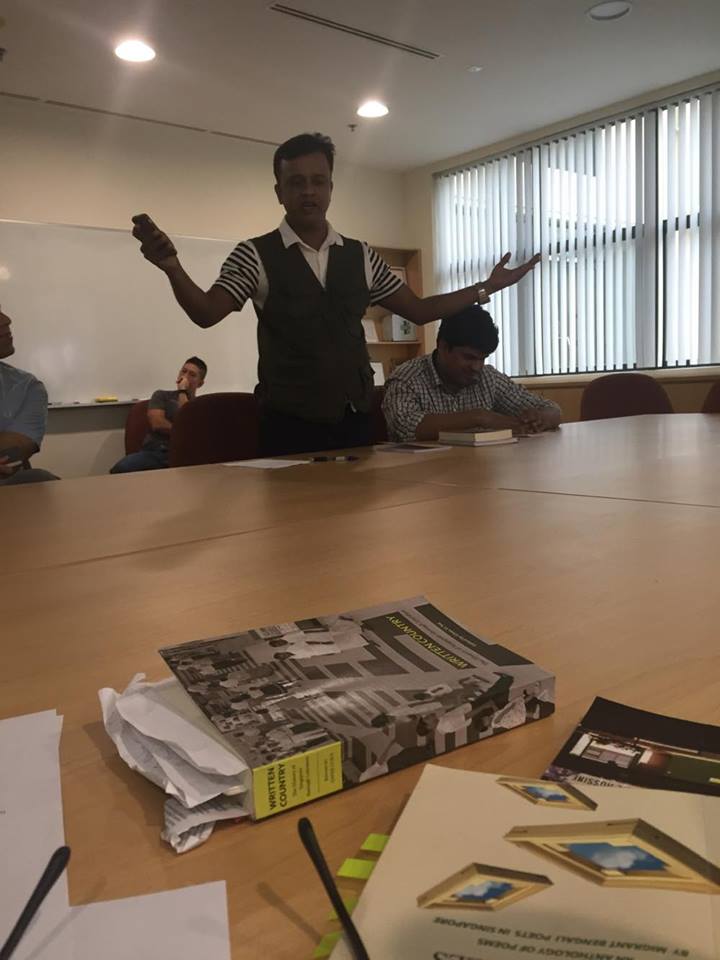

l-r: Masud Opu, Richard Angus Whitehead, MD Sharif, Mohor Khan

This paper is largely based on a talk I gave at the National Institute of Education. My profound thanks to my friend, Singapore teacher, expatriate of Kolkata, and poetry lover Surya Banerjee for patiently and evocatively explaining the Bangla terms to me. I am indebted to Jee Leong Koh for reading an earlier draft of this paper and commenting perceptively with illuminating suggestions. Ultimately, many thanks to MD Sharif, MD Mukul Hossine and the their fellow Bengali migrant poets for their friendship and for sharing so candidly their poetry and a glimpse into their processes of writing in Singapore.

Angus Whitehead is Assistant Professor in Literature at Singapore’s National Institute of Education. A William Blake scholar, Angus is co-editor with Mark Crosby and Troy Patenaude of the essay collection, Re-Envisioning Blake (Palgrave, 2012). With an ever-growing fascination and engagement with Singapore writing, he has edited two collections of short stories by pioneer Singapore writers: Arthur Yap and Gregory Nalpon. He edited (with Angelia Poon) the first collection of critical essays focusing solely upon Singapore Literature directed at a global readership: Singapore Literature and Culture: Current Directions in Local and Global Contexts (Routledge, 2017). His chapter ‘”stick it to the pimp”: Peaches’ Penetration of American Popular Culture’ is included in Tristanne Connolly and Tomoyuki Lino eds, Canadian Music and American Culture: Get Away From Me (Palgrave Macmillan, forthcoming 2017).