Art Is + Esther Vincent

SP Blog’s series "Art Is +" is an attempt to view art through the eyes of artists and writers themselves. In wide-ranging interviews with vital new artists and writers from both Asia and the USA, the series ushers these voices to the forefront, contextualizing their work with the experiences, processes, and motivations that are unique to each individual artist. "Art Is +" encourages viewers and readers to appreciate art as the multitude of ways in which artists and writers continually engage with our world and the variety of spaces they occupy in it. Read our interviews with Symin Adive, Geraldine Kang, Paula Mendoza, Zining Mok, JinJin Xu, Leonard Yang, Monique Truong, Noorlinah Mohamed, and Vithya Subramaniam.

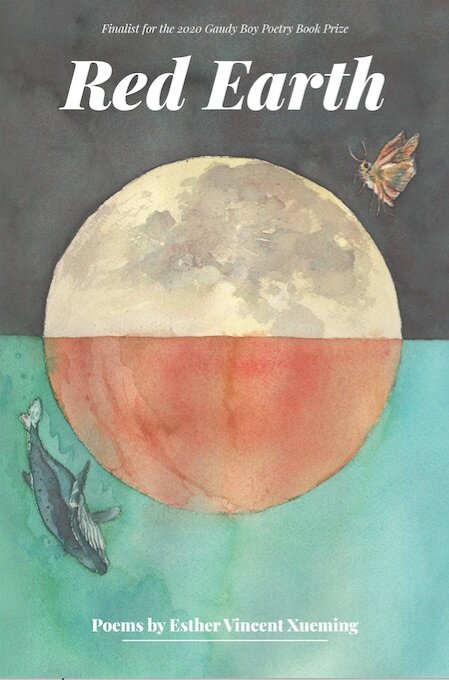

Esther Vincent Xueming is the author of Red Earth (Blue Cactus Press, 2021) and editor-in-chief and founder of The Tiger Moth Review, an eco journal of art and literature based in Singapore. She is co-editor of Making Kin: Ecofeminist Essays from Singapore (Ethos Books, 2021) and two poetry anthologies, Poetry Moves (Ethos Books, 2020) and Little Things (Ethos Books, 2013). A literature educator by profession, she is passionate about the entanglements in art, literature, nature, and the environment. Follow her on Twitter @EstherVincentXM

[Photo credit: Ethan Leong]

Esther Vincent’s debut collection Red Earth turns the lens of eco-poetry on global instances of climate destruction, including the Singaporean landscape. A poet of memory and connection, Vincent alerts us to a new way of seeing Singapore and our planet – one of care and attention. Red Earth invites us to approach nature with awe and devotion, reminding us that to be on Earth is to be responsible for its care, no matter which country we consider home. Through dreamscapes, fieldwork, and theoretical meditation, Red Earth creates a space of possibilities, one that imagines a new, careful way of being in the world. – Janelle Tan

“I like to think of eco-poetry as its own form of eco-activism. In writing and reading about our earth, we pay attention to our earth, and in doing so,

we cultivate care and love for our earth. Care and love are powerful ingredients for any kind of movement or social change.”

Janelle Tan: I like to start by asking all the poets I interview: what is a poem to you?

Esther Vincent: A poem to me is a work of (literary) art that hopefully opens a reader to new ways of seeing, imagining, and being. It is image and sound, conveyed through words and form, and as with any art form, it requires attention and care. Every poem is an act of love, and therefore it needs to be read with similar attention and care in order to be able to be ushered into a state of arrival.

JT: Why write poetry? What kind of potential and possibility do you see in the form?

EV: Someone once said the form chooses you, and not the other way round. I did not choose poetry. Poetry chose me. It’s hard to explain but that’s the simple truth. It’s intuitive and you just have to trust it.

Jane Hirshfield writes that “Language is sought, and seeks. The poet, pursuing a vessel to hold something known, finds what the poem may know that the poet as yet does not.” In working on Red Earth, I have come to understand what she means by this.

I also like to compare poetry to meditation. About the same time I began working on Red Earth, I began my practice in meditation. Hirshfield writes about this extensively and what I want to share is how she relates poetry to attention and consequently, compassion. Mary Oliver similarly describes attention as the “beginning of devotion”. To write a poem, it requires a mind of concentration, of devoting oneself to the craft, and to the subject of the poem. In such an attentive meditative state, one achieves clarity and truths are revealed.

To write my poem “Falcon” for instance, I spent five months from October 2020 to January 2021 doing fieldwork, which included observing a migrating peregrine falcon across from my window with my binoculars (I was lucky that this was one of the falcon’s roosting spots, and this was the second year it had returned). I kept a log of its activities, documenting its roosting habits, as well as its successful hunts. I noted its physical appearance, and I did additional research to make sure I got the specifics right. I paid close attention to the falcon and read up about its migratory patterns and behaviour. I attended to the bird with care and devotion.

Yet, the poem would not have been complete without my dream. In one dream, I observed a large grey heron perching on top of an emergent tree of a forest canopy, against the full moon. The image is so vivid, so poignant, so surreal. I knew the heron was related to the falcon in some way, the bird of my dreams and the bird of my waking moments were speaking to each other, different and the same. I knew they would meet in my poem. That is one of the possibilities of poetry, to offer intersections and new ways of being.

JT: I’m really interested in the sense of the mystical and mythical in Red Earth. The reality of climate change in Singapore is portrayed as violent, even apocalyptic, but you invoke myths and goddesses in your poems. For example, a whale glued together by plastic trash outside a museum becomes connected to the goddess Sedna. Do you see your relationship to nature as a kind of reverence?

EV: I agree with the bit on violence (so much of our engagement with the earth has been founded upon violence), but I think my poems steer away from the apocalyptic. Yes, there is grief, which Donna Haraway describes as “the path to understanding entangled shared living and dying; human beings must grieve with, because we are in and of this fabric of undoing.” Grief is a kind of “sustained remembrance” and I think my poems engage with grief and violence as a way of remembering. On top of that, my poems also remind readers (and myself) of the importance of hope in imagining alternative ways of seeing, being, and living on earth.

I often find myself in awe of nature, and as my poems reveal, I see myself as a part of and not apart from nature. We come from the earth, and we are composed of the earth. Scott Gilbert, Howard A. Schneiderman Professor of Biology, says, “We are all lichens.” What this means is that we are symbiopoietic organisms; our very existence is founded upon our multiple entanglements and partnerships with diverse others.

JT: Another instance of this myth-making is in the poem “Yogyakarta triptych,” where you write, “We leave, learning of gods that create,/ preserve and destroy./ Like them, we too make and break/something each day.” How do you see the environment, and climate change, as connected to myths and the sacred?

EV: We are not individual, autopoietic beings (this is the myth we are told); we are made possible through the relational (this is the story I try to tell with my poems). So, the whale in my poem “Whale dream” can be read as an ancestor or spirit guide of sorts, and the speaker in the poem as a whale-child/daughter, half woman, half fish, who looks to the whale for guidance, support and direction. In searching, she finds various iterations of the whale-mother from both her waking and sleeping moments. There are goddesses like the Inuit goddess of the sea Sedna, there is the reference to the Bruges whale (or Skyscraper Whale) composed of 150 million tonnes of marine plastic waste, and there is the humpback whale of the speaker’s dreams. These whales are multitudinous—and here I recall Walt Whitman who writes in “Song of Myself, 51”: “(I am large, I contain multitudes.)”—but they are also one and the same, sharing the same “heartbeat,” which the speaker learns is also hers. In writing the poem, I found that the whale and I were separate and one, and that I think is one of the powerful things about poetic and mythical un-making and re-making, when they take on personal meaning for writer and reader.

Similarly, in “Yogyakarta triptych,” I use the form of the triptych, traditionally associated with early Christian art, to interpellate world religions like Buddhism and Hinduism. This poem re-presents these world religions as accessible yet indecipherable to the speaker, who is not a practicing Buddhist or Hindu, but who seeks spirituality at these sacred sites nonetheless. The poem as triptych gathers and unites rather than divides, reminding us that we are all seekers, journeying across time and place, and that like the gods of our ancestors, we are divine beings, divinity residing within.

“And poetry is a little like that, isn’t it? It’s journeying

into the darkness, like Inanna’s descent… into the seven layers

of the underworld, each time losing a part of herself,

eventually dying to be reborn.”

JT: In the first section, you present several different dreams. A teacher of mine once said, the power of invoking dreams in a poem is that you can be as wild as possible. I’d also add to that, mystery and symbolism. What do dreams allow you to enact in poems? For you, what is the imaginative power of a dream?

EV: A poem is not a dream, and a dream is not a poem. But many of the poems in Red Earth are inspired by my dreams, lucid and vivid, as well as altered states of consciousness.

My dreams are a gateway to my subconscious, allowing me to engage with the world intuitively, through signs and symbols. Often, what happens in my dreams is not physically or logically possible during my waking moments. I think that drawing from dreams is one of the most powerful things to do in poetry (and art), because you’re essentially drawing from the well of the deep, from the unutterable and unknowable, the parts of yourself and consciousness that can only be accessed when your ego is no longer in charge.

And poetry is a little like that, isn’t it? It’s journeying into the darkness, like Inanna’s descent (“The art of meditation”) into the seven layers of the underworld, each time losing a part of herself, eventually dying to be reborn. Dreams are like death, and to access a dream is to access one’s shadow, which I find to be the power of dreams. They speak truths you dare not utter awake (“Red Earth”).

JT: In the title poem, “Red Earth”, the speaker says, “The earth as a metaphor for my body,/ vast and unknowable.” In your work, the body becomes a site for thinking about nature, and nature becomes a way to think about the body. The speaker then says, “I use words/ to paint a scene of red earth, vast and unknowable.” Do you think of the title poem as a kind of ars poetica?

EV: I think the poem “Red Earth,” which evolved from its original form into two lyrics (“Awake” and “Asleep”), embodies the poetics of my book—which searches for harmony, duality, and balance in darkness and light. The two lyrics present two versions of the earth, one awake, one asleep, material and embodied, symbolic and disembodied.

The self, and by proxy, the earth, can never fully be known. Parts of the self and earth will always remain hidden from us, and I think this poem tries to convey this theme—of knowing, unknowing, and unknowability, secrets that can never fully be plumbed.

JT: I’m struck by the specificity of place and physical spaces in this book. It is as if we experience them with you, but there’s also a sense that the symbolic space your poems inhabit allows us to revisit and reshape our memories of a place. I’ve been thinking about how each time we recall an event from the past, our brain alters it, and with each subsequent recall we move further from the original experience of the event. How does memory play a role in Red Earth’s depiction of place?

EV: My poems are symbolic spaces that readers can enter and inhabit. This reminds me of Martin Heidegger’s “Building Dwelling Thinking” where words and language can serve as dwelling places for the body. In taking the form of words and language via poetry, memory takes on the material. My poems are largely autobiographical, yet in their very construction, they have become something completely new, hybrid, and autonomous of mere recount. My poems locate my speaker in specific sites, places, or bioregions, but they also re-imagine the speaker in sites of conflict, trauma, love, loss, and longing.

Memory is a fluid thing. And that’s the beauty of memory. It resists containment and regulation. In some ways, memories are like dreams too, they are recollected moments we yearn for or wish to re-enter. They expose our desires.

I turn to memory for specificity and accuracy of experience. In remembering, I navigate desire, and my poems, as dream-memory-desire serve as bridges or portals into dwelling on earth. They ground themselves in the concrete and tangible, in objects which function as the loci of memory, like stones or a photograph, and they hold space for the clarity that comes from recollection.

JT: How do you create and imagine a place, knowing that the act of writing and revising changes our experiences of a space? How do you revisit and reshape a place within your process of writing and revising?

EV: Matsuo Basho uses the metaphor of being “earthbound and present in the here and now, and yet open also to… the everlasting self, the boundlessness of inner as well as outer space.” I try to do that with my poems, to ground the speaker and reader in a familiar sense of place that is present in the here and now, while being open to the boundlessness of the imagination.

A poem is a re-writing and re-envisioning of place. Each reading of a poem is an inhabiting of the poem, which takes on different meanings for different readers, or for the same reader at different moments in time.

I typically need some distance from the moment, experience, or place before I can write about it. Sometimes this means a few days, at other times a few years or even decades. Distance gives me clarity, and usually I begin a poem with a line or image. The poem then takes its shape and is shaped by what it needs to say. I don’t consciously ‘decide’ how to re-create or re-imagine a place in my poems. The process is more intuitive—there’s an element of letting go of the need to control and of the conscious self, to learn to trust and let the subconscious take over, in order for the poem to fully come into being. The poem comes into its own, has its own presence and breath, and as a poet, I have learnt to see myself as merely a vessel or receptacle.

JT: You’re the founder and editor of The Tiger Moth Review. As a journal with a specific focus on nature, culture, the environment, and ecology, how did the journal come to be, and what do you hope to accomplish with it?

EV: I founded the journal in Oct 2018 because at that time, I had started writing more eco-poems, and found that there weren’t platforms locally that were devoted to publishing eco-themed work. I found this disturbing but I decided to seize the opportunity to create such a platform where none had existed. At that time, I was teaching in SOTA, which led to my interest in interdisciplinary work, which is why The Tiger Moth Review publishes eco-themed art and literature.

My hopes for the journal include making space for visual and literary works that, to quote Jonathan Bate loosely, sing to the earth. I have a very broad and generous definition of eco-themed work, because I want to be as inclusive as possible. The journal continues to prioritise work from the region, but we pride ourselves on representing diverse voices from around the world.

JT: You must read a lot of work about the environment for The Tiger Moth Review. What do you see is the role of poetry within a larger awareness of and movement against climate change?

EV: To me, eco-poetry, as poetry that contemplates our place on earth as home, is one of the many ways in which we can contribute to a better earth. I like to think of eco-poetry as its own form of eco-activism. In writing and reading about our earth, we pay attention to our earth, and in doing so, we cultivate care and love for our earth. Care and love are powerful ingredients for any kind of movement or social change.

Poems too can serve as dreams or visions of hope and possibilities, and in doing so, can provoke or inspire movement work.

Ecopoetry acknowledges the threats of human existence on earth while envisioning ways of living on earth more responsibly. The poems of Marshallese poet and climate activist Kathy Jetn̄il-Kijiner for example, show how poetry can participate in environmental discourse and create awareness of climate change.

“By paying attention to and in place, a landscape, tiger moth,

or migrating egret can move from being beautiful

to evoking some deep and hidden emotions in us,

or transform from the aesthetic to the symbolic and spiritual.”

JT: As a Singaporean poet, do you think about your positionality when responding to instances of environmental destruction globally, whether in your work or when reading submissions?

EV: Carson McCullers says that to know who you are, you need to have a place to come from. Eavan Boland writes that “what we call place is really only that detail of it which we understand to be ourselves.”

Yes, we are all beings located relationally in time and place, and for each of us, this takes on different meanings depending on our intersectional identities and contexts. For some of us, this might highlight our lack of power, for others, their privilege is cemented.

As a woman poet situated in this place called Singapore, I think about myself in relation to this land that I am not indigenous to, and I wonder about the lands of my ancestors. I think about the violence inflicted on the land and its peoples, and I think about the violence I implicitly participate in or am culpable of. I think about how we are all connected, and how different people and more-than-human beings experience climate change differently.

I think about my place and relative mobility as I move across the earth in my travels, and I think about how I relate to these places as a transient visitor, a pilgrim of sorts seeking out home away from home on earth. In some ways, my poems try to grapple with the notion of “eco-cosmopolitanism” a term developed by Ursula K. Heise, which reimagines human and more-than-human beings as part of a planetary community and consciousness. This is antithetical to the ways we have been schooled as part of national curricula to think of our identities as tied to nation, citizenship and/or along geopolitical lines. I think climate change reminds us of our inter-connectedness (we share this one earth and we are all responsible, yet some of us are in fact more responsible than others), which I hope the reader will be able to realise from reading my poems.

JT: I see Singapore so vividly in this collection – the small patches of grass, the trees among the streets, the construction and highways, the sea and the wind. There’s a sense in your work that we can find earth in the everyday. What do you gift attention to in your everyday landscape?

EV: Thank you. I believe it was Tony Robbins who said, “energy flows where attention goes.” To pay attention, one needs to slow down. The art (because it requires skill and imagination to invent an alternative way of relating to time and to others) and act (because we need to take tangible action to change our behaviours) of slowing down requires us to attune ourselves to a different rhythm, the rhythms of nature which do not flow in sync with the homo sapien’s conception of time, schedules, or routines.

I believe the books I read as a child, books of fantasy like The Magic Faraway Tree and similar stories that allowed children to re-imagine their relationships to nature shaped my early conception of human-nature relations, nurturing in me a desire to find the magical in the mundane from an early age and continuing into adulthood. I think beauty can be found anywhere, and while I won’t deny that some landscapes, especially more ancient, spiritual ones, like The Burren in Ireland or Prambanan in Yogyakarta, inspire awe and wonder more so than others, it’s down to the individual to see familiar places with new, childlike eyes.

Anything can fascinate me, as my poems will reveal—from an article I read to a childhood memory. I see the landscape of the everyday on two levels—what Seamus Heaney and later Eavan Boland refer to as the “country of the mind,” an imagined and enhanced sense of place re-entered and experienced via memory and imagination, as well as the literal landscape. The former holds cultural associations, myths, and symbolic meanings tied to the place, and so contains the spirit of the place as well. The latter is more objective and scientific in the sense that it refers to the aesthetic, literal, geographical space, which may evoke awe in the viewer, but without histories and meanings.

I think both ways of relating to place can and should be honoured. By paying attention to and in place, a landscape, tiger moth, or migrating egret can move from being beautiful to evoking some deep and hidden emotions in us, or transform from the aesthetic to the symbolic and spiritual.

JT: Red Earth seems to emphasize the natural landscape in Singapore that people take for granted. Because Singapore is so urban, Singaporeans are so alienated from the nature that surrounds them in small capacities at every turn. I’m curious about how you practice living with an awareness of the natural. How do you see Red Earth navigating the urban daily life that comes with living in Singapore?

EV: As you rightly point out, we are surrounded by nature. Granted a lot of it is engineered and manicured (and taken for granted), but a tree is still a tree and it still participates in an ecological network of services where it is planted and grows. It still provides a home for the multiple and diverse critters that inhabit it, it still offers us shade. Its roots travel underground, symbiotically relating to fungi in mycorrhizal associations for mutual benefits; its work continues beyond our reach.

I hope Red Earth encourages readers to contemplate their place on earth, as well as their relations and ways of relating to other person-beings, human and more-than-human. I hope Red Earth inspires readers to envision a different way of being on earth, one that is more present, attentive, and caring for others in our midst, and to our ways of living and dying on earth. I hope Red Earth reminds readers of the beauty of our earth, and consequently, our responsibility to love and cultivate our earth and home for generations to come.

JT: Singapore has grown in size by almost a quarter through land reclamation, and you touch on this in “Albatross,” where the speaker says, “how strange to fill the sea with sand, to reclaim/ water into unsinkable land.” I’m thinking of the notion you put forth that to build our own urban landscape we take from another’s earth. Who do you hope Red Earth reaches with this message?

EV: Yes, this poem was inspired by Kalyanee Mam’s documentary film Lost World and a visit few years back to Pulau Semakau, which resulted in an earlier iteration of the poem “Throw me into the landfill.” During the editing process, I found that the poem was trying to hold too much in one poem, and so “Albatross” was born to stand on its own, apart from but still related to “Throw me into the landfill.”

I think many Singaporeans are ignorant of or complacent about the fact that our landscape is socially engineered. What this means is that there is a lot that is unnatural about the landscape, as well as the way we relate to the land and sea, and the beings that inhabit the land and sea. Hills have been flattened, forests cleared, ecosystems destroyed. When we ran out of land from within our borders, we turned to our neighbours to satiate our appetite for growth.

The ethics of taking from another without giving back in return (and I don’t mean monetary relations, which are transactional and never equitable), I think is what I grapple with in my poem. Nature teaches us that the best relationships that flourish are the symbiotic, reciprocal ones, and yet, I witness and live on a land governed by a one-way mode of relations that benefits the taker while disadvantaging the giver.

“What I hope we realise is that the violence we give returns to us.

If we love our earth more, our earth would be able to love us back

more fully in return. So in some ways, violence begets violence,

but the earth has also taught me about forgiveness and hope.”

JT: You’re also an educator. Does your work with students intersect at all with your work with the environment? Does the kind of Earth we are leaving behind find its way into your work as an educator?

EV: Yes, as much as possible, I try to incorporate the teaching of eco-poems in the poetry curriculum. I also conduct workshops on eco-poetry and eco-feminism, which have so far been well received. It’s quite clear that I’m passionate about the work I do with my journal and my own poetry, and I would say this translates into the way I select, teach, and talk about poems and environmental issues in the classroom.

JT: Given the ambition of Red Earth, I have to ask: how long did it take for you to find a home for this manuscript?

EV: Some poems have taken decades to write, others a number of weeks. Before working on the manuscript, individual poems from Red Earth were published in various journals, anthologies and magazines, but the entire manuscript started to take shape over the two years I was working on my thesis. I spent close to a year sending out my working manuscript and receiving one rejection after another.

I find it poetic and apt, considering the ethos of the book, that Red Earth had to journey halfway across the world to a small press in Tacoma, Washington, USA to find a home before returning to Singapore.

JT: I’m struck by the sense of awe and violence that filter through Red Earth. I think that to write about nature is to hold onto a sense of awe, but it is also about grief: what we have lost, and the fight the land puts up. I get a sense that to write about humans in nature is to write about killing. What do you hope Red Earth contributes to the literature about climate change and the environment that is out there?

EV: Yes, there is a lot of violence involved, and I think that we need to hold ourselves accountable to the amount of violence we have inflicted and continue to inflict on others—our earth, other people, our more-than-human companions.

What I hope we realise is that the violence we give returns to us. If we love our earth more, our earth would be able to love us back more fully in return. So in some ways, violence begets violence, but the earth has also taught me about forgiveness and hope. The sambar deer in “Crossing” for instance has taught me to forgive and let go of anger and bitterness, and to cross from the path of inherited trauma into the path of healing. Nature has taught me to be still, present, and reverent, like the granite cliffs of “Little Guilin” or The Three Sisters in “The Blue Mountains,” and the falcon in “Falcon” has taught me patience and resilience during harsh times.

There’s so much to learn if we humble ourselves and look to nature to teach us, and to remind us that we too are part of nature—a younger child in the genealogy of the natural world but a relative nonetheless.

I hope Red Earth does just that—help us locate ourselves relationally in time and place on this earth and offer a new, more attentive and devotional way of being on earth.

Janelle Tan was born in Singapore. Her work appears or is forthcoming in Poetry, Mass Poetry, Michigan Quarterly Review, No Tokens, The Margins (AAWW), Nat. Brut, and elsewhere. She holds an MFA from NYU, where she was Web Editor for Washington Square Review. She is a Brooklyn Poets fellow and Assistant Interviews Editor at Singapore Unbound. She lives and teaches poetry in Brooklyn.

If you’ve enjoyed reading this article, please consider making a donation. Your donation goes towards paying our contributors and a modest stipend to our editors. Singapore Unbound is powered by volunteers, and we depend on individual supporters. To maintain our independence, we do not seek or accept direct funding from any government.