A Death: Scenes, Thoughts, and Memories

By Ali Hatami

Ramtin Zad - Kamal Ol Molk (2007), acrylic on canvas, 150x200cm

Image description: An impressionist-style painting of a scene with a field of pale-blue and pink flower-buds across a yellow-and-orange landscape. In the center of the foreground, an upside-down rooster is suspended by one foot. On the left of the rooster, a nude, orange-haired woman looks upwards while clutching a pink flower by the stalk to her chest. Below her is a patch of turquoise. In the bottom right corner of the painting, a balding, old man with white hair and small, round, wire-framed glasses holds up a dice between the thumb and index finger of his left hand. Behind him, a copper-haired woman wearing a red dress stares downwards wistfully while propping her head on her left hand and holding the string of floating, red and yellow balloons in her right hand. In the top right corner of the painting, a crow sits on the horizon.

Jino and Maryam get out of the car. He looks out at Jino in her school uniform – a navy-blue manteaux and headscarf – with her backpack on her shoulders. She turns to say goodbye. Her first day of school. Her seventh birthday, too. Seven . . . seven years since she was born and his father passed away. Thinking of Jino’s birth always reminds him of his father’s death.

He thinks of his mother, who would always remember his birth date through her uncle’s death. According to his birth certificate, he was born on the first day of Farvardin – that is, Nowruz. It was always kind of interesting to him that he had been born exactly on the day of Nowruz. He knew, however, that back in the day, in their village, like most villages in Kermanshah region, parents such as his didn’t care much about the exact birth dates of their children, simply because in their world it was really of no use nor importance whatsoever; people would get birth certificates for their newborns only sometime after they were born. Usually, it would happen like this: either the father went to town and got birth certificates for his newborn child, or a registry office worker would come to the village and administer the birth certificates. Sometimes, it would be quite a while after the child was born, and the fathers, most of them being illiterate, would not remember the exact birth date of their children. Not to mention that the official and local calendars were different! So the birth dates were never accurate, and mostly just an approximate month, day, and time. Mothers would remember birth dates better, but they too were illiterate, and pegged the birth date not to the official calendar but to an important, simultaneous event, so important that they couldn’t forget it, and, many times, that important event was the death of someone – a close relative or a prominent figure.

That was why his mother, whenever his birth was mentioned, would always say that he was born exactly on the day that Asad, her uncle, died.

He had always laughed at this synchronicity, this strange unity of death and life. He had thought it a sad and yet funny way to remember the birth of someone! He had never thought that the same would happen with his own father and daughter, that the death of one and the birth of the other would be forever united, that being reminded of one would inevitably mean recalling the other.

It’s been seven years now. Now, Jino is beginning a new period in her life, just as seven years ago, some things changed in his own.

***

Almost a week earlier, he attended a job interview. He had had many jobs since he moved to Tehran as a student for a Master of Science in accountancy. He had gone from one organization to the next, then to a company, then to a bank, then to another bank and so on, all of them paying him enough money to get by and maybe a little bit more, but that “little bit more” was never that much. And now, Jino was going to be born in a week or so, and he was thinking of getting a better job, once again, with a better salary.

The job was for a big development company, the interviewer being the company owner himself. He had been recommended by a mutual friend, Mr. Sadeghi, his old professor. The company owner was a middle-aged man, nicely dressed, relaxed and friendly, yet not talking too much or giving any false impressions, unlike most of the other interviewers he had met. A couple of minutes into the interview, which consisted of short questions about his personal and professional background that he answered in a reserved yet slightly passionate and friendly way, the company owner said to him, "Let me be honest with you. I kind of like you. I think you are quite good at and passionate about your job, and Mr. Sadeghi, too, speaks highly of you, emphasizing that you’re a hard worker, which is a great but rare quality nowadays. And if it is true, which I guess it is, then we can work together." Then he pointed to a picture of an old man on the wall behind him, and at a wooden wand on a rack on the same wall. He went on to tell him that everything he had he had inherited from his father: a strong and willful farmer who, through hard work and power of character, had been able to collect enough money to buy his son, a new graduate, some tools to start a company. He had asked nothing from him in return, but to continue his spirit of hard work and not to forget from where he had started. And it was that money and that spirit on which this whole company had been built.

In response to the company owner, he said that he was not afraid of work but really enjoyed it, and all that he asked for was to be paid fairly. Then, mentioning his father, he said that he, too, got it from his father, a simple and hardworking man who had inherited a small, rocky, useless piece of land from his own father, but had worked on it tirelessly, removing the rocks and turning it into a fertile field. After a couple of years, he had bought another small piece of land, and after a while, two cows. Today, they had more than twenty cows that they took care of in their own yard, selling their milk. There were those two pieces of land too. His father and mother, despite all the difficulties, had brought up five children, raising them on those cows and parcels of land, as best as they could.

He didn’t say more to the company owner, but when he finished he was still thinking about his parents. He didn’t get emotional like this so often. Just like his father, he was a serious and taciturn man who could even be dismissed by others as sullen, yet sometimes, when thinking about his parents, he felt this way.

Back then in his childhood summers, after the main crops, such as wheat, barley, and pea, were done, his father would truck the land. As school was closed in the summer, sometimes he would help his father. He saw how his father worked. It was hard work, but he didn’t get tired, he didn’t take many breaks. Sometimes when a relative visited, he would sit down with them, but he always seemed impatient. He wasn’t much of a talkative person; he didn’t seem to have many things to tell others. Many times, he would find an excuse to get back to his vegetables. The only time he did take a break was for tea and cigarettes, and the break was over as soon as he drank his tea and smoked his cigarette. Coming back home at night, he would wash, eat supper, and then ask for a pillow. He was left-handed and used to press his right elbow on the pillow, stretching out his legs, smoking and talking to them – asking them about their day or talking to them about things that had happened in the village, or among the relatives, or anything else. Sometimes, he would joke or play with them. Evidently, he felt different about talking to his children than to others – he seemed to enjoy it. After a few hours, he would feel tired and sleepy. He used to sleep early and wake up early as well.

His father wasn’t the only one leading a life like that – the men of his father’s generation in the region could generally be divided into two groups: a noble and almost-wealthy minority and the average majority who mostly owned one or two small pieces of land and a small flock of sheep. Taking care of the land and sheep required constant, unbroken, hard work while, given the fact that most families had many children, the income would suffice only to make ends meet. When the modern era touched these people, their only wish was for their children to get educated, hoping they would find easier, more rewarding jobs, such as being a civil servant, so that they could have a better, more comfortable life than the kind of life their parents had. This tough life had turned many of them into bitter people who were often nagging, even sometimes blaming their children for their miserable lives because they believed they had gone through it all only for the sake of their children. They hoped their children would be grateful and make amends to them when they got to be educated, work as civil servants, and all.

His father belonged to the latter group, the only difference being that he was not bitter, nor did he nag. He didn’t think his children owed him anything and didn’t expect them to make it up to him. His wife and children were his world. It was the same with his mother too. She had taken pains to raise him and his siblings, so much so that she was nothing but skin and bones, yet she was never sore at her children and rarely nagged at them.

His parents, when they were young, before they decided to get married, had loved each other. His paternal grandfather had opposed the bond because the girl his son loved was not a close relative, but his father had insisted on marrying the girl he loved, so the only inheritance bestowed on him was that small, rocky, useless piece of land. His parents, after so many years, still loved each other. They even had a reputation among relatives of being lovebirds, and sometimes other family members joked about them.

Maybe that was the reason they treated their children differently, committing themselves to them, doing everything to raise them as best as they could, so that they would become someone for their own sake. And they had made it, more or less – all five siblings were educated, had jobs, were generally on good terms with each other, treating each other just the way their parents had treated them.

That was why he felt good when he was reminded of his parents, but, on the other hand, thinking about what they had been through made him sad. Another reason why he felt at once happy and sad about it was maybe because, after all, he didn’t consider his life to be better than theirs. Seemingly, he had a good job, being an expert who was more than welcome to work in many companies or offices – so if he didn’t much like working in one place, he could easily go somewhere else and work there, not ever fearing joblessness. But it wasn’t like he didn’t need to care about money. He had been able to rent a rather nice house in Tehran – where the rental prices were going up day by day – he had a Samand and could make the ends meet. That was all. He had seen how easy life was for some other people, for instance, his uncle Faraya and his children. When he was but a young man, Faraya, supported by his father, had moved to Gilan-e Gharb, and had bought a store. His second wife’s family, being rich, had also supported him. Some years on, he had become almost a rich man, moving to Kermanshah, and then, later, to Tehran. He thought he deserved that fortune too, just like Faraya. They were no better than he was. He had been a good student right from the start and had always wanted to have a good life. He was smart, capable, and skillful. He had worked day and night, caring about work more than anything else. Ha had tried hard to begin a business, yet all of his efforts had proved futile. First, he had wanted to import medical equipment, but, after a while, he had realized that there was no chance for him against his state rivals. Then he had entered into a partnership with a friend to buy a dump truck and export cement to Iraq with it, but a turn in the market meant they had to sell the dump truck and forget all about it. After that, he had made friends with some people from the Netherlands who were selling prefabricated pieces of ski resorts, fairgrounds, and so on. He had tried to act as a mediator and find them buyers and investors from Iran, but again it was all in vain. So, when he thought about it, what he saw was that he, too, just like his father, had always worked – only maybe his work not quite as difficult as his father’s – but, in the end, he hadn’t become rich as he had wished.

And now he was attending another interview – for a job that, he hoped, would be a little better. In the end, he told the company owner that there was only one problem: his wife was due to give birth in a week or so and so he would need a few days off then.

***

He was on his way back home. It was almost 3 p.m.. Lately, he had been coming home earlier to be with Maryam, not staying till 7, or even 8, at work as he used to. Suddenly, his mobile phone rang. An unknown number. First, he didn’t want to answer, but, right at that moment, he arrived at a crossroad and the light turned red. He didn’t know who the man on the other end of the line was. He was saying, I’m a neighbor of your parents’, one of the sisters is sick and has been hospitalized, and you’d better come home if you can.

Even now, after seven years, he didn’t know who this caller was, but the calls went on. The second one came from Pejman, his cousin. What he said was, your father has had an accident, but don’t worry, it’s nothing serious, only his legs have been injured.

Those who called all said different things, but they mostly mentioned his sisters Laila and Shirin. He suspected that something had happened, yet they didn’t want to tell him about it straightforwardly. Eventually, after stopping at another red light, he called Pejman again, insisting to know the truth, and . . . it came out: his father had had a brain seizure all of a sudden and had passed away, just like that. He had been coming down the verandah stairs to pay a visit to a relative who had been in an accident, and right on the last stair, he had fallen. He had been taken to the hospital instantly, but the doctors had said he’d died at the moment of the fall.

All of a sudden, time turned into something heavy, it seemed to have stopped, to have lost the strength to go forward, like heavy, sticky water. He was stuck in it, moving his hands around, yet unable to get out. He felt his body was swollen, so swollen that he had lost the ability to do anything. He looked at his hands – they were so inflated he hardly could hold the steering wheel. The entire world had inflated, everything around him had gotten so big they couldn’t move. His skinny face had become so inflated he could hardly breathe. The entire world seemed to have turned into that heavy water. He didn’t know how long it lasted, but all of a sudden, he heard the long, crazy beeps. All the cars behind him were beeping. The light had turned green, and he could still breathe.

***

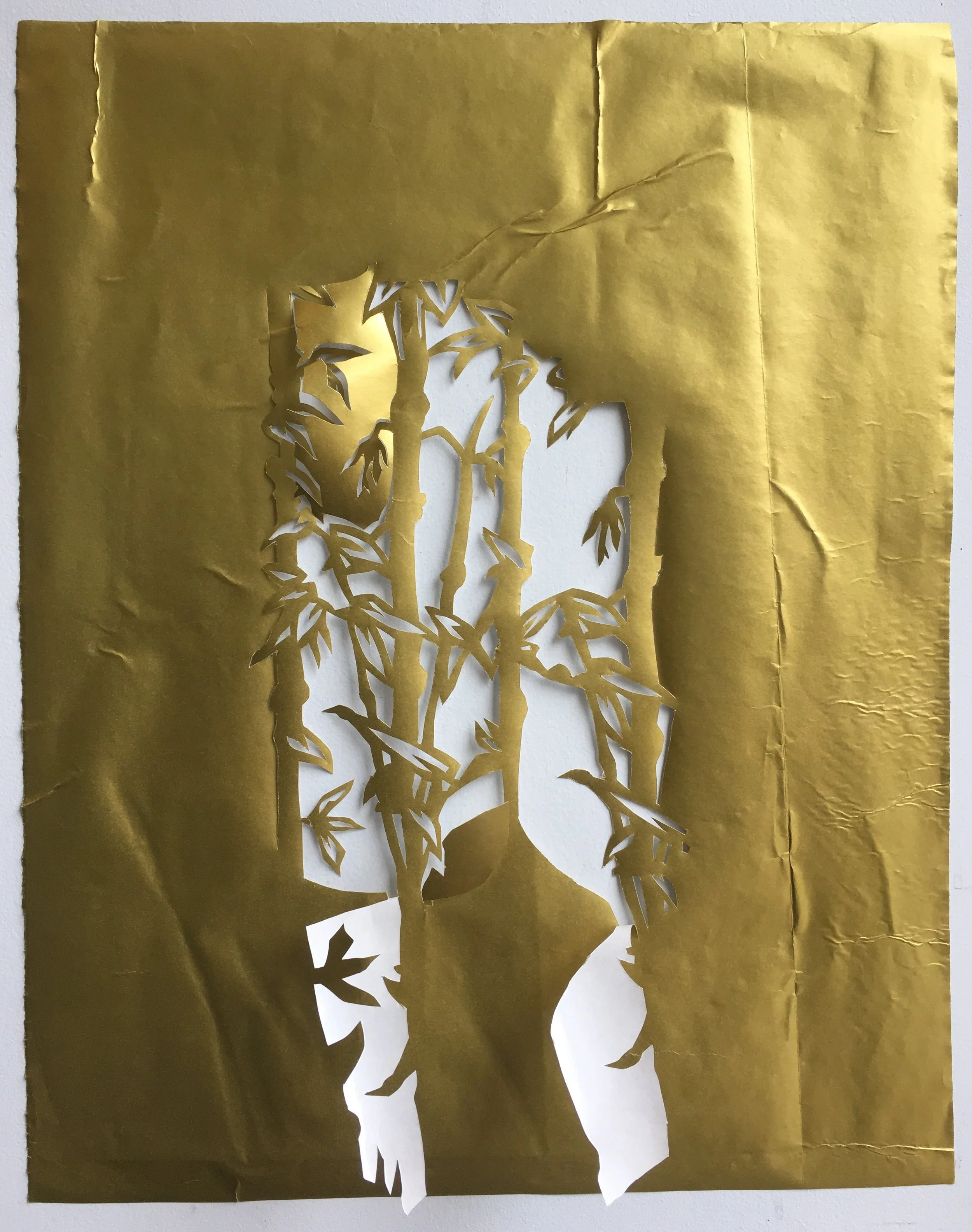

Ramtin Zad - Untitled (miniature series), 2008, acrylic on canvas, 180x240cm

Image description: An impressionist-style painting of a surrealist scenario featuring several flying crows in the foreground against a turquoise background. A brunette figure in the bottom right corner, wearing a red blazer with a swirly pattern and a white, ruffled undershirt, controls a floating, orange ball between their hands. The scene is mostly framed by gold embellishments that morph into a white rooster head and three human heads in the center of the painting. In the bottom left corner, pink roses complete the framing of the painting.

The road from Tehran to Kermanshah, then from there to Eslamabad-e Gharb, then from there to Kefrawr, and finally from there to Dar-e Baru — a road he had taken hundreds of times, alone, in company, at night, during the day – he had never imagined its meaning could change so dramatically. It had somehow stretched out, and he couldn’t get to the end of it. He was like someone who wanted to get somewhere nearby as soon as possible, running towards his destination, yet as he got close, it kept getting away. He was running and running, growing short of breath, his legs aching, his soles on fire, but still he couldn’t get to the end of it.

The things he encountered along the road – their meaning had also changed: the lonely, distant trees, the buildings, other cars, other people . . . he had never paid attention to such things when taking this road before, but now, he couldn’t help it. It seemed as if each one of them had something to say to him, and he was waiting for them to say what they had to, but none of them said anything. A few times he felt like it was all a dream, and he was waiting for one of them to come and wake him up, but none of them did that either. All of them were quite silent, even a couple of people he came across weren’t talking clearly, and he couldn’t make out what they were saying.

It wasn’t just those things. The meaning of the whole world had changed, and the change could be seen in everything – evening lights that were giving way to the long shadows, giving way, little by little, to the darkness, which was spreading over everything. His own hands were shaking, and all of a sudden, he remembered he couldn’t drive like that and had to hold the steering wheel tighter – in all of these things, the world seemed to have changed forever.

As he got closer to Dar-e Baru, his heart started to beat faster. A couple of times he stepped on the gas too hard and almost lost control of the car. On the dirt road between the main road and the village, a road that was hardly more than a kilometer long, driven through in a minute, that sense of the road stretching was gone. But he had the thought that he had been in that car since he was born, stepping on the gas to traverse this one-kilometer dirt road but not making it yet. When he got close to the village, he saw a gathering of people, who made their way towards him. He didn’t stop till he reached his parents’ house. There was a black piece of cloth on the yard door, on which was written in white: ‘It is with a heavy heart and tearful eyes that we mourn the passing of a beloved father . . . ’. He got out of the car and went into the yard. More people were coming towards him, his sisters among them. They started crying and scratching their faces as was the custom. He put his head on their shoulders. His mother appeared too. He put his head on her shoulder too. Later, whenever he thought about it, the only thing that brought him comfort during those sore days of the memorial service were those generous shoulders given to him so compassionately.

***

The commotion, a noisy mess of men and women – there were maybe five hundred people there. It was the memorial service. People came and left in groups. They came and said the prayer, then were brought to houses to be fed, and as they left, another group would arrive. They placed their hands on their chests as a sign of respect, quickly uttered their condolences and were gone, except for those who were closer relatives who stopped and made their condolences longer. There were almost one hundred men in the row of the mournful, most of them standing, some sitting on the small plastic chairs provided for them. In the breaks between the coming and going of guests, they talked to each other, playing with their rosaries. And there were those who had taken it upon themselves to manage the ceremony. They were moving around restlessly, talking loudly, sometimes shouting, giving orders to their helpers, trying to take care of everything as best as they could. From inside the house came the sound of women’s wailing and crying.

It was disturbing to him, all of these endless, unnecessary rituals that seemed to have no purpose other than distancing you from the tragedy, not letting you face it directly. But amidst it all there was something happening to him. He felt his ears suddenly sharpen; he was able to hear every sound. His head was bowed. He didn’t raise it except when someone came and talked to him directly, but it was as if amidst all the noise and hustle and bustle he could make out all the sounds and voices with precise clarity. He knew what the two lads standing across from him and talking quietly were saying. Most of the things he heard he had heard before, maybe hundreds of times, and they were always daily, pointless, trivial talk, but now, all of a sudden, some of them seemed different to him, meaningful, in a way. They came back to him, and, consciously or unconsciously, he kept thinking about them.

Suddenly he heard someone saying, “... lost a dear one, will never laugh fearlessly again.” He turned to where the voice was coming from. It was an old man, sitting a few seats to his right, talking to a younger man. He didn’t know who he was. His hair, mustache, and beard were all white as snow. His hair, soft yet a little curly, was combed upwards, and he had a clean and fitted suit on. He kept staring at the ground. Even when he was talking to the others, he didn’t look at them, as if looking was a difficult task for him. His movements were so slow that one could find it hard to believe that he could move at all. It was as if a sculpture had come to life, moving slowly and uncertainly, not having learnt yet to move effortlessly.

The old man’s words became one of the sayings he kept wondering about. He even repeated them a couple of times to those he felt comfortable talking to. He had heard the words before; they seemed to be a kind of proverb, but he had never given them any thought. All of a sudden, how true the saying seemed to be.

***

He was thinking about strange things, things he usually didn’t bother to think about. He had always been busy working, not caring too much about how things were, but, now, amidst all the commotion, he couldn’t help thinking about such things.

Among them was his uncle Faraya, who had died in a car accident five years ago. Being the eldest among his siblings – Faraya was a few years older than his father – he had inherited a rather vast piece of land. He had moved to Tehran with his family, but, until his death, he would come home each summer to take care of the crops on his land and visit relatives. During those visits, Faraya mostly stayed in their house, residing in the room in the right wing. He and his siblings, when they were kids, used to call that room Uncle Faraya’s room. It was the first time he recalled it after so long. One midnight, so tired he thought he could no longer stand on his feet – he hadn’t slept well for a few days – he made his way to the same room. He looked around it for a moment. It was nearly twenty square meters and almost empty. They didn’t use it that much; it was mostly reserved for guests. It had two narrow yet high windows from which the big oak tree atop the hill on the right side of the village could be seen. It was peaceful and quiet.

It had been a couple of days since the memorial service, and there weren’t many people around, only two of his aunts who had wanted to stay with his mother. Saying he’d like to sleep in Uncle Faraya’s room, he asked for his bed to be made and added that a blanket would do. He lay down in bed on the blanket and covered himself with another one. Uncle Faraya used to leave the door and the windows open so that the sweet, cool breeze would blow in.

Faraya was quite fond of him. He used to say, you and your siblings are good children, you are good to your parents, and so on. Like many old folks in the region, Faraya admired him for his smarts. He always asked him to sleep in the same room, so his mother or sisters would also make a bed for him there. Every night Faraya would talk to him for quite a while. He was a seasoned man, had been through a lot, and so talked to him about lots of things. One thing he enjoyed talking about was his first wife, Shazenan, who had died at a young age. Faraya talked about her passionately, saying she was of unmatched beauty. Then he would go on about how, around the year 1955, he had succeeded in marrying her. They were cousins. There had been many suitors for Shazenan, some of them rich and prestigious, but being madly in love with her and knowing that Shazenan had a crush on him too, Faraya had told everyone, she’s my cousin and will be mine and only mine. Faraya told him at length about all the crazy, funny things he had done to win Shazenan. However, he didn’t remember well this part of Faraya’s story. It was general and blurry in his mind and seemed trivial to him. There was another part regarding how Shazenan had died, and it was this part that he remembered most and kept thinking about. After marriage, Faraya and Shazenan had moved to Gilan-e Gharb, and Faraya opened a big grocery store there. Two years passed. Shazenan had a younger brother named Shapoor. One night Shapoor suffered from a fever, shivers, and a stomachache. He was taken to the only clinic in the town, and the doctors gave him some medicine, yet he died in the morning. Later they found out that his appendix had inflamed and burst. It was winter, and that night a heavy rain and snow had covered the ground with mud and sleet. In the morning, Shapoor was buried. Shazenan, who was very fond of her younger brother, wailed hard, throwing herself into the snow and mud, and her clothes were wet all over. The body was supposed to be buried in Milail, a cemetery on a hilltop outside the town. Back in the day, there were not many cars in the region, and the mournful had to go and come back from the cemetery on foot while the burying itself took a long time, so it took Shazenan a long time to return home and change her clothes. Afterwards she was wheezing and coughing, but no one took it seriously, thinking she’d just caught a cold and would get better soon. After a while, the sickness worsened, and Faraya took her to Kermanshah. They said that it was tuberculosis and Shazenan was sent to Tehran. Faraya took all the money he had, bringing Shazenan to Shahabad’s Tuberculosis Sanatorium in Tehran. There she was treated for a year, after which the doctors said she’d recovered, there was nothing to be worried about, and Shazenan returned home. A year passed during which she was in good health, but then she started to vomit blood. Again, Faraya took her to Tehran. After a few months, she got better and was due to return home in a few days, but one morning, all of a sudden, she worsened. Moments later, she died in the arms of Faraya before the doctors arrived. Faraya, all alone, buried her in Shabdolazim all by himself.

When Uncle Faraya told him about it all, he didn’t say much, just listened out of respect. Rarely he asked questions and gave serious thought to what his uncle was saying; it all seemed quite trivial. That night, in the room of Uncle Faraya, though – after many years – he couldn’t help thinking about what Uncle Faraya had told him. He felt like he was listening to his uncle’s stories for the first time, like he was only just now understanding them. He thought about how alive Shazenan had remained for Faraya in spite of all the years that had passed since she had died. Faraya had married again and had four children; still, he scarcely talked about them, not in the same way he talked about Shazenan, his voice so passionate, so full of excitement.

He remembered Faraya’s death. A car accident – he had run into a truck. He had visited him at the ICU. Faraya was in a coma. He held his uncle’s hand in his for a moment. He felt Faraya squeeze his hand as if he wanted to say something to him. Coming out of the ICU, he saw his cousins quarrelling over the inheritance. The next day, Faraya passed away.

***

Ramtin Zad - Gonbad series (Ephialtes), 2007, acrylic on canvas, 150x200 cm

Image description: In the red-hued, impressionist-style painting, lying at the bottom is a pale-skinned, white-haired, old man in a red-and-pink, striped shirt in a cot-like bed. He is presumed to be deceased as his hands rest on the stalks of purple flowers on top of his belly. The flowers are the same flowers visible in the foreground. On the right of the painting, a man with a handlebar mustache and a large, yellow hat looms over the bed, staring down at the dead, old man. In the top left corner of the painting, a distressed-looking woman with curly, brown hair, wearing a long-sleeved, pink shirt with blue stripes, stretches her hands over her head.

He watches Jino, waving at him and laughing.

The day after his father’s death, Maryam had called him up, saying, it’s time, and I’m going to the hospital. She had a brother in Tehran. She had told him, I’ll ask my brother to come and stay with me in case I need to be taken care of. It was 10 p.m. when Maryam called. He left for Kermanshah at once. The day before, too, he had wanted to take a flight, but there were no flights to Kermanshah until the next morning, and he, not able to wait, had decided to hit the road. This time there was a flight at 12, and he was lucky to catch it at the last minute. Almost at the same time Jino was born. He didn’t know what to do: to laugh or to cry. In the morning, he came back to Dar-e Baru to attend the memorial service.

Now, seven years later, a lot has changed. It all started with his father’s death, his first real contact with death. It was unexpected – his father wasn’t that old, only sixty – and he was a healthy man, hardly sick, a healthy eater. Except for smoking, he had no habits that could jeopardize his health; his sudden death had come to everyone as a shock.

After his father died, the road from Tehran to Kefrawr changed forever. Sometimes, when travelling, he would look at the things along it, and in doing so, he would wonder if, once again, they had something to say to him. Sometimes the heavy water surrounded him again. Many times, he had this feeling of loss. Yet, after his father’s death, strangely enough, everything also became alive for him. His father had increasingly become more alive, and he would remember things about him that he hadn’t paid attention to or cared about before. He remembered the way he used to smoke at night – the way he laid his right elbow against the pillow, holding his cigarette in his left hand, puffing it gently and slowly, tapping off its ash even more gently and slowly. He realized how peacefully his father used to smoke, as if, after a day of hard work, he couldn’t ask for anything more than that simple ritual. Thinking about it, he felt that his father was pleased with life, more or less, or – at least – at night he was, when he smoked and talked to his children.

When he was a student, he had picked up smoking for a while, but he quit later. Yet, in those later years, recalling how his father used to smoke would occasionally prompt him to have a cigarette. It wasn’t like when he was a student. Back then he mostly smoked when he felt sad, but now he did it mostly out of pleasure. Recalling how his father used to smoke made him want to feel the same – to have time for himself, thinking of nothing, only doing what he really enjoyed doing, enjoying life, enjoying being still alive, before that inevitable end arrived. He still enjoyed working, and worked hard, but he no longer wanted to kill himself over it.

***

One Friday evening, nearly two years after his father had passed away, being alone – Maryam and Jino had gone to Ilam to visit Maryam’s family – and having nothing to do, he felt bored. He killed some time by trying to watch something on TV and doing some work around the house, but he still felt bored, and he didn’t feel like visiting friends or anybody else. Finally, he decided to go for a ride and welcome whatever might come his way.

He drove around aimlessly for a while, not having anywhere special to go to. Finally, a place came to his mind, but he hesitated, hoping he would think of, or come upon, another place. After a while, totally surprised by what he was doing, he found himself on his way to Shabdolazim.

He only remembered this much that Uncle Faraya had told him, that Shazenan’s grave was close to Sattar Khan’s. By the time he got there, it was around sunset. People could still be seen around the shrine, the last of the pilgrims, who wanted to perform their pilgrimage quickly and go back home. The only soul in the yard was an old man sitting by a grave. He went to him and asked if he knew where Sattar Khan’s grave was. The old man showed him the way. He found Sattar Khan’s grave easily, but couldn’t tell which one was Shazenan’s. He remembered Faraya had told him Shazenan’s grave was a couple of graves away from Sattar Khan’s and a little bit to the left, but the problem was there were no names on some of the graves there. He searched for a while among the graves, but he found no graves bearing the name of Shazenan. He thought maybe hers, too, was anonymous, and, his uncle, not imagining in his wildest dreams that one day his nephew would visit it, hadn’t felt the need to tell him about it.

After searching for almost a quarter of an hour and having found nothing, he got tired and decided he’d better go, but right at the moment, some sparrows appeared, perched on a grave in front of him, and, after a moment or two, they flew away. He looked at the gravestone on which the sparrows had perched. It was reddish and had no name engraved upon it. It occurred to him that maybe that was Shazenan’s grave, and the idea made him laugh. He stopped for a moment and looked around. Long shadows of the sunset had spread everywhere, and all around it was quiet, as if the sun was calling upon everything to take a break at last, after a long day. He remained still for a while, the tranquility of the moment getting under his skin. He thought it made no difference which one of those graves was Shazenan’s; he just felt like enjoying the silence and serenity of the moment. He sat down by the grave where the sparrows had perched, giving himself up to the sunset. After a while, though, he realized that his mind was still busy with Shazenan. Suddenly, it occurred to him that now he must be the sole person in all the world who was thinking of Shazenan, though he did not know much about her, except for the little things his uncle had told him. He remembered Faraya. He wondered about the time when Shazenan was hospitalized in Tehran. How had it been for them, for Faraya and Shazenan? During that time Faraya must sometimes have had to return home, to sort out the business and things, but most of the time he had been by the side of Shazenan. How must it have been for Faraya to see Shazenan like that, sick, weary, far from her gracious days – the very Shazenan whose grace and beauty would go on to haunt Faraya, after all those years. Maybe it was a relief for them to be together. What about Shazenan? How had all those days gone by for her, days of loneliness, days when all the world had been reduced to the hospital walls? What could she have possibly been thinking about? Faraya? Her kin? Home? Shapoor? Had Shapoor, after death, become more alive for her too? Perhaps, given the fact that she needed something very dear to hold on to in that loneliness. What about when Shazenan died? How had it been for Faraya to bury the love of his life all by himself, all alone?

Faraya didn’t talk much about those parts of his story. He had talked more about Shazenan’s beauty and how he had managed to win her over. Despite being a seasoned man and respected by people, Faraya was always so calm and quiet, talking in a soft, low voice, walking slowly and peacefully, every one of his movements the same, always laughing, yet laughing quietly. He couldn’t recall any loud laughter from Faraya. True, when he talked about all the funny, crazy things he had done to marry Shazenan, he talked faster, was evidently excited, and laughed frequently. He couldn’t recall Faraya being as excited and happy as then. Yet, even then, he was so calm, talking in his usual low, soft voice. He was like a timid boy who had done something naughty and funny and couldn’t wait to tell others about it, but when it came to telling, he got shy and did it shyly. His father and mother used to say that Faraya was not acting like himself. Since he was a kid, he had heard them say it all the time about Faraya, and they believed the reason to be homesickness, Faraya being away from home and kin, and they blamed his wife and children for making him move to Tehran.

Faraya never talked about such things, just as when he talked about himself and Shazenan, he didn’t go through the unhappy parts, not delving into the details about how he had buried Shazenan all alone. He thought maybe Faraya was so courteous and considerate that he considered it improper to tell others of his pain and suffering; or maybe this part of the story was so personal for him he didn’t wish to talk about it; or maybe remembering and consequently talking about this part was too painful for him, whereas it felt good to talk about the beauty and grace of Shazenan and how they had married and stuff like that; or maybe these were just his thoughts, and he showed more interest in this part of the story because it suited him. After all, he and Faraya had lived in two completely different times, and it was probable that Faraya himself had never thought about his story in this way.

He had been at the graveyard for almost half an hour. Now it had gotten dark everywhere. He had been completely distracted by the tranquility of sunset and darkness. Finally, he got up to go home.

***

He still thought every now and then about Faraya, Shazenan, his father, and other people – dead or alive – who might return to life for him in unexpected ways.

After his father’s death, whenever he went back to Dar-e Baro, he slept in Uncle Faraya’s room during his visit. He was usually a late sleeper. Sometimes he felt like Uncle Faraya, like wanting to talk to someone. He thought that maybe Uncle Faraya, too, couldn’t sleep, and that was why he had wanted to talk to him, and the idea made him laugh.

Sometimes Jino came and slept with him, especially when they were in Dar-e Baro. She was so curious, asking all kinds of questions about very different things. You had to go on and on answering her, but she would still not be satisfied and would go on to ask more questions. Sometimes he thought, maybe one day he’d tell her all about it – Faraya, Shazenan, his father and mother, how Jino herself had been born, and all.

Jino blows kisses at him, laughing, then waving and jumping all over again. It makes Maryam laugh, him too.

Ali Hatami was born in Kurdistan, Iran. He is a multilingual writer, writing in Kurdish, English and Persian.

*

Born in 1984, Ramtin Zad graduated in fine arts in his native city of Tehran, Iran. Where he established his career as a figurative painter and sculptor.

In his narrative paintings armed with bold colors, thick brushed and stroked detailing, Zad is focused on religious and mythical references on cycle of nature, the repetitive notion of constant decay and revival of birth and…. revolving in small and large scales.

Zad has continuously exhibited his art works internationally in several solo and group exhibitions with galleries, private collectors and museums including Tehran, Dubai, Basel, Kuwait, London, Beijing, Turkey and New York since 2006.

If you’ve enjoyed reading this article, please consider making a donation. Your donation goes towards paying our contributors and a modest stipend to our editors. Singapore Unbound is powered by volunteers, and we depend on individual supporters. To maintain our independence, we do not seek or accept direct funding from any government.

‘But later… we didn’t talk about love. We talk about the land and its people.’ – a short story by Kaushik Ranjan Bora, translated from the Assamese by Aruni Kashyap.