Beauty and the Jinn

By Rahad Abir

-

This story contains sexual violence to children.

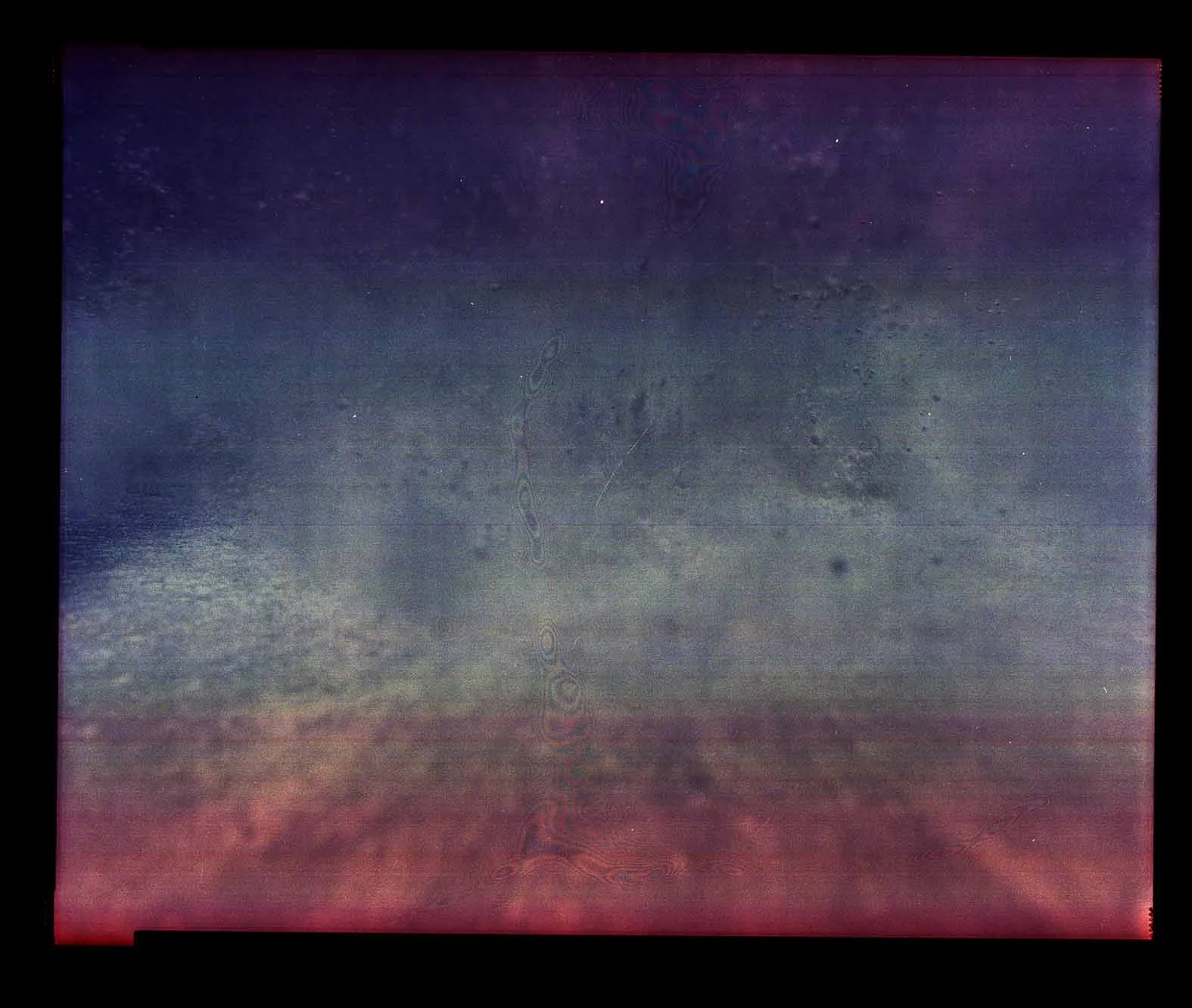

Sheelasha Rajbhandari, Agony of the New Bed 1 (2016)

Image description: Portraits of Nepalese women and girls of different ages are printed on cotton mattresses placed on miniature golden matrimonial beds. Each portrait is covered with scribbles, texts, and metaphorical images embroidered with golden and red thread.

They say the girl is jinxed. Her mother died the day she was born. Six years later when her brother died of a snakebite, the father put the blame on her. Why didn’t you die in his stead? he said. Girls are meant to end up in their husbands’ houses. Who will look after me when I get old?

The girl has no friends. Women are wary of letting their children play with her. They always wonder how this poor girl called Beauty got such fair skin.

**

Beauty comes to the mosque with the other children for her morning Quran lesson. Some days I cannot stop looking at her. With big eyes and lush eyelashes, she has the face of a memsahib. Her hair is long and crow black. One day after the Arabic lesson, I tell Beauty to stay. You sweep the yard, I say, then go home.

Girls and boys leave the booklets and book-rests on the shelves before rushing out. They have been at the mosque since a little after the dawn prayers. Now, after an hour of reading at the top of their lungs, they are hungry and ready to run homeward.

Beauty waits. She sees everyone scurry away. One of the girls looks back at her, giggles, and makes off.

Beauty goes off to sweep. Pearl white prayer beads in my hand, I sit inside by the door and watch her measured movements. Halfway through her job, I call to her. Beauty drops the broom, slowly walks in, and stands before me.

How old are you? I ask.

Eleven, she says.

Sit down. I stroke my beard to gather my words.

Beauty hesitates, but does as told.

Remember my words? If I’m pleased with you, Allah will be pleased.

She nods.

You must do whatever I say. Keep in mind that my prayers can open the gates of heaven for you. But if I’m angry, I curse you, and you go straight to Jahannam.

I get up and shut the door. Eyes narrowed, Beauty gazes at me. I kneel down beside her and draw her to me. She wriggles like an earthworm trying to free herself from my tightening clasp.

This stays between you and me, I whisper in her ear. Don’t tell it to anybody. Otherwise I’ll curse your father, and he will die.

Let me go, Beauty flinches. Her voice quavers. Her face is bleached with fear.

**

I clean up the mess between her legs and help her to her feet. She is in tears, shaking slightly.

Don’t cry, I say. You are fine. I remind her of my warning. My curse can kill her father. What will happen to her then? Her stepmother will kick her out of the house. She will end up begging on the street. Does she want that?

Beauty sniffles. I know she won’t open her mouth. The girl won’t risk losing her father when her stepmother treats her no better than a maid.

I unlatch the door. With short, slow steps, she shambles off the mosque veranda, then trudges across the yard, waddling like the ducks nearby. Her little figure disappears inch by inch behind the rain tree.

I bite my lip and sigh. Sitting down, I pull my beard bitterly. A blood spot on the hogla mat catches my eye.

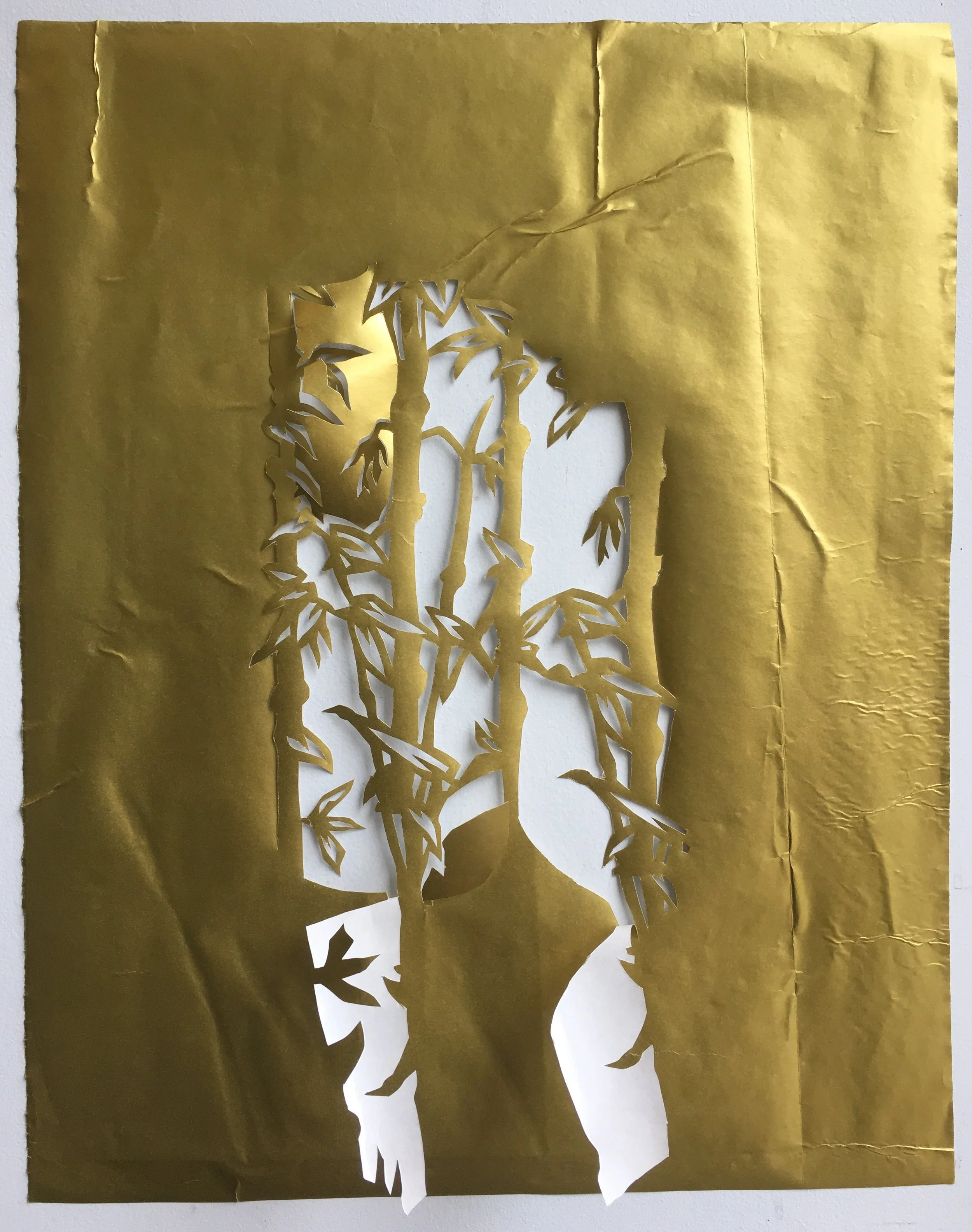

Sheelasha Rajbhandari, Agony of the New Bed 2 (2016)

Image description: A close-up shot of the portraits that shows more details of the golden bed frames. We also get a better view of the different women featured in each black and white portrait and the embroidery designs covering their faces.

**

Beauty has been absent from the morning Arabic lessons. I ask one of her neighbor girls. Beauty’s sick, says the girl.

One evening, right before the Isha prayers, Beauty’s father enters the mosque. My heart hits my rib cage hard. A tremor seizes me the whole time I lead the prayer. When the worshipers leave, Beauty’s father approaches me.

Imam shaheb, he says, I have a small problem.

I hold my breath.

Beauty. Something is wrong with her.

W-what? I stammer.

She won’t go to school, won’t come to you for the Quran lesson. She’s gone very quiet and timid.

Aha, I say in relief.

He scratches and lowers his head. He says that Beauty has been whining about abdominal ache and that her mother found out she has gotten her period. He pauses. And there’s another issue, he says. Beauty wakes up screaming in the middle of the night.

I stroke my beard for a minute. It seems, I say, she’s been caught by a dark wind. She must have gone under the banyan tree at a bad hour.

Oh no! cries the father.

Don’t worry, I reassure him. Come tomorrow morning with a clean bottle of water.

**

The following morning Beauty’s father returns.

I murmur some duas and suras to myself and blow into the bottle. Have her drink the water twice daily, I instruct him. In the morning on an empty stomach, and at night before going to bed. Within seven days she’ll be normal, inshallah.

The father pays me a small fee, salaams, and leaves.

**

He visits me a week later. She hasn’t improved at all, he tells me. She doesn’t play. Doesn’t speak. Besides, she seems to be afraid of men.

Hmm, I say, stroking my beard. I will make a special tabiz for her. Give me a couple of days.

**

Nothing’s changed with the amulet, Beauty’s father complains.

I need to see her in person, I say.

It is afternoon when I arrive at his house. I am seated in the veranda and hear yelling emanating from the back room. No, I won’t go, Beauty howls.

The father drags her in front of me. The girl has grown thinner since I saw her last. Her head is hanging, dark hair blocking her profile.

Remove her hair from her face, I bid the father. The father complies.

Tell me what’s bothering you, I say to the girl. Beauty, look at me. Lift your head.

The father straightens her head. But Beauty keeps her eyes fixed on the dirt floor.

Look at me, Beauty, I say louder. Can you hear me?

Beauty flings a stabbing glance at me, and, without warning, spits.

The father starts slapping her. The saliva feels hot against my face, burning my cheeks. I mop it with a kerchief.

Stop beating her, I blurt.

The father stops. Imam shaheb, maaf please, he keeps repeating. He asks me to forgive him and his unruly daughter.

Beauty is possessed, I announce.

Possessed? mutters the father. He turns pale.

Yes, a bad jinn. I pause. These evil spirits like pretty girls with long hair.

Ay hai, he breathes. What will happen now?

There is treatment. I will come tomorrow.

Before I am back at the mosque for the evening prayers, the entire village is abuzz with Beauty’s possession. They say that Beauty is bewitched by a gigantic wayward jinn. They whisper that she drenched me in demonic spit.

**

I sit on the chair in the yard in front of Beauty’s house. Men and women and scores of children are scattered around, waiting to watch me get rid of a jinn. Beauty is brought before me. Her hair is tied in a bun. I take a long moment to finger my beard. Then humming suras from the Quran, from time to time, I blow my breath on her, softly clap my hands and release them toward her.

Go, go, go now! I shout. Go this minute! You devil, go this minute! I walk around her blowing my breath. Last warning, devil! I roar, leave her now! Go back where you came from!

I sit back and ask Beauty’s father to get me a coconut broom. He fetches one. I tap it on her right and left arms. She stares at me, eyes taut and bloodshot.

Go, go, go, I yell. Go away, right now! The broom bashes against her back, arms, and legs. You devil, tell me where you come from? Why did you take her?

Beauty’s eyes are fixed on me.

Look down, I cry. Look down. But she glowers instead. I detect a demon in her eyes. The broom in my hand goes wild, whacking her nonstop. She convulses with every blow.

Take her, I command the father. Dip her in the water ten times.

He pulls her to the pond. I stand at the edge and count the dipping.

The father gets out of the water lugging her sopping body in his arms. Beauty is panting and shivering.

That’s all for today, I say. We start again tomorrow.

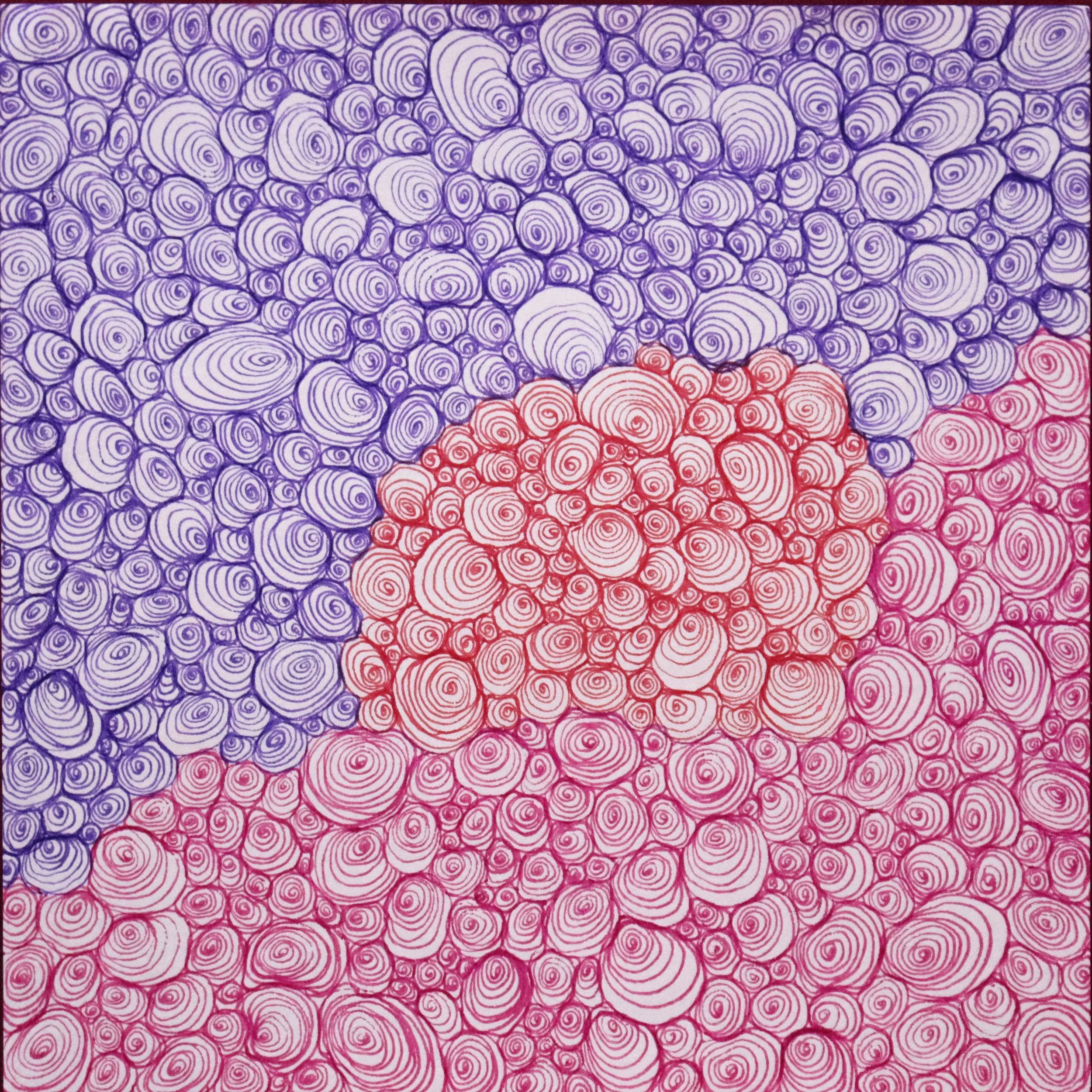

Sheelasha Rajbhandari, Agony of the New Bed 3 (2016)

Image description: A close-up, side-angled view of two of the bed frames. The bed at the top depicts the black-and-white headshot of a woman in a hijab with an embroidered gold scribble covering her face. The bed below has an extreme close-up of a different woman’s face with red and gold embroidered lettering.

**

The next day I chop off her hair to her chin. As her tresses fall rippling in a heap around her, I catch a collective oh dear! resonating among the women onlookers there. Beauty makes no sound. Her glare at me is fiercer than ever. I sprinkle holy water on her face. Her eyelids do not drop.

I smack her arms with a fresh broom. She whimpers, shaking all over. Tears drip down her cheeks, her ivory arms flashing with red streaks. I order the father to dip her twenty times. When he climbs up carrying her, Beauty looks awfully small—limbs dangling from her trunk. Her teeth chatter.

I inform the father that the girl is taken over by the worst jinn I have ever seen. This jinn can just set his eyes upon anyone and possess that person. That is the reason, I explain, that Beauty stares all the time.

I instruct him to keep her separate in a room and give her only one meal a day. I hand out amulets for everyone in his house.

The father thanks me to his best ability. For my continued service, he places a five-hundred-taka bill in my palm.

**

Panic plagues the villagers. Stories go around that Beauty frequently bursts out laughing and crying. They can even hear her from their houses. I hear that they walk away upon seeing Beauty’s father on the street. They have stopped visiting his house and keep a strict watch on their children so no one can go near that jinn-possessed den.

I make tabiz amulets all day. Villagers pay me in advance and wait for hours outside the mosque to get their holy lockets stuffed with Quranic verses. Everyone wants a safeguard against the silent staring demon.

**

After the dawn prayer, some village elders sit with me at the mosque. They ask me to find a solution for Beauty. The ostracism of her family has to end. The girl’s family is suffering, they say. They hesitate for a while, then suggest that I marry the girl. The father is happy to offer me a moderate dowry.

For a moment I cannot speak, I think of her death glare. A possessed girl, I say, shaking my head.

You can cure the girl, they say. She will be okay. She is a good girl, you know.

Yes, I know. But she’s still a child.

She is almost twelve—a marriageable age. And—they add in a hushed tone, she has bled. She is a woman now.

I do not respond.

They whisper to each other. They hold my hands and plead with me, saying that this is the only way to resolve this.

We don’t see any problem with it, they say. You’re young too.

I keep silent. They say Beauty’s stepmother is pregnant; she is expecting a boy. By no means can she allow a jinn-possessed girl to live in the same house.

They assert that Beauty will at least be useful in doing my household work. She can cook, clean and wash my clothes.

I give my consent.

They fix next Friday for the wedding.

**

That night, I toss and turn in bed, thinking about the coming wedding. I remember the day with Beauty at the mosque. I let out a sigh looking back on the afternoon I cut her beautiful hair. I imagine her long hair falling off in a heap around her. I try to sleep, but in the dark I see Beauty staring at me. I get up and light the hurricane lamp. Yet the flame of the lamp seems glaring at me.

The story “Beauty and the Jinn” appears in Our Many Longings: Contemporary Short Fiction From Bangladesh (India: Dhauli Books, 2021), edited by Sohana Manzoor. Published by author’s permission.

Rahad Abir is a writer from Bangladesh. His work has appeared or is forthcoming in Prairie Schooner, The Los Angeles Review, The Bombay Literary Magazine, The Wire, Himal Southasian, Courrier International, and elsewhere. He has an MFA from Boston University. He received the 2017-18 Charles Pick Fellowship at the University of East Anglia. Currently he is working on a short story collection, which was a finalist for the 2021 Miami Book Fair Emerging Writer Fellowship.

*

Sheelasha Rajbhandari, born in 1988 in Kathmandu, is a visual artist, cultural organizer, and co-founder of the artist collective Artree Nepal. Her longitudinal research repositions quotidian and plural narratives, by weaving folktales, oral histories, and performative rituals as a juxtaposition to conventional historiography. Rajbhandari’s practice is rooted in the experiences of women and seeks to confront how female agency and corporeality become contested political sites for contemporary nation-states, a phenomenon that parallels the dismantling of matricentric landscapes in extractive societies.

If you’ve enjoyed reading this article, please consider making a donation. Your donation goes towards paying our contributors and a modest stipend to our editors. Singapore Unbound is powered by volunteers, and we depend on individual supporters. To maintain our independence, we do not seek or accept direct funding from any government.

‘But later… we didn’t talk about love. We talk about the land and its people.’ – a short story by Kaushik Ranjan Bora, translated from the Assamese by Aruni Kashyap.