Mi Hermana, El Tierra

By Sigrid Marianne Gayangos

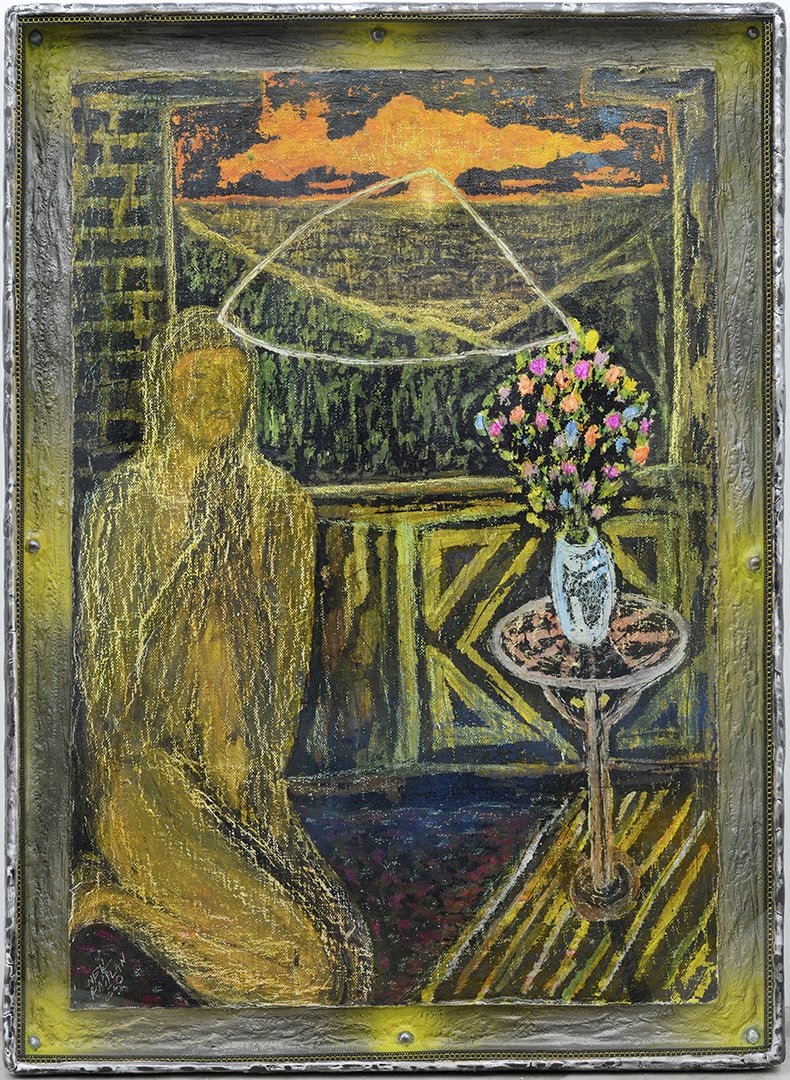

Neil Pasilan - 3 Bonding (2020), Mixed media on canvas

Image description: A painting of a faceless figure kneeling on the floor by a window with a view of an open field and an orange sunset. This figure is also kneeling in front of a small circular side table with a glass vase holding a bouquet of pink, orange, and yellow flowers. There is a white triangle at the top of the image with each point uniting all three of the subjects. The overall painting is also in a yellowish-green hue.

Haaay, mira, I really have nothing to gain from faking this, okay? Imagine all the work it would take, and for what? Para ginda mio cara na di inyo newspaper? I have done that and more in my younger years. 1964 La Hermosa Festival Miss Zamboanga, look it up. From tabloids to broadsheets, they had pictures of me in my beautiful mascota! See, I’m getting old. My sister’s story did not die with her; but when I do, it will with me. Telling it to you now, and of course you decide for yourself whether you believe it or not, then perhaps, her story will yet live another life. I know, I know, you’re doing your best not to snicker and you’re just indulging this fool of a vieja. But, allow me to show you the room at least—

Mio hermana, you remember, was a journalist like yourself. But when she wasn’t busy writing news stories, she was busy capturing stories in a different form: pictures. Go ahead, browse through those albums—I have more stacked in the office room—but these, these were some of her best shots. She was wild, passionate and willful and you can see how she willed herself into the subjects she captured here in these glossy, colorful spreads of magazines and these leaflets for various NGOs. I remember browsing through the raw shots on her computer when we were younger, the dense canopy of the oldest wani tree in Tumaga, the cascading water against the mossy tiered wall of rocks of Merloquet, wildflowers in full bloom up in the forest of Abong-Abong. Ah, mira aqui, the animals were her favorite, here a closeup of a bent-toed gecko clinging precariously to a plant stem, the elusive red-eyed black galansiyang. She would lean down over my shoulder and talk me through the whole experience of taking the photos, explaining how she would carefully crouch or patiently wait it out just to capture the perfect shot.

Then she would disappear for months, armed with just a rucksack containing her basic necessities and camera. And after each trip, when she returned home to us in downtown pueblo, she seemed less and less comfortable among us. Back then we lived in a tiny apartment on Pilar Street; this little bungalow I now stay in was rented out to a starting family. Buen familia, OFW el tata. She snapped at me one time, when I brought home a Beatles vinyl record I had borrowed from a friend, and delivered an impassioned speech on how pop-culture was the global capitalist’s tool. I was only 14 and didn’t really understand what she was going on and on about… I just wanted to listen to the Beatles. It was for this reason, among many others, that my sister and I grew apart and lost touch. When our mother died, followed shortly by our father, it was as though the feeble thread that linked us together had finally snapped. That is, until her letter reached my doorsteps in Dumaguete.

I had just moved to the city then, traveling from one seaside area to another, taking on odd jobs. I don’t mean to brag, but with a face like mine, I was able to land quite a number of modeling jobs with little to no effort. Maskin onde yo ta anda, pirmi tiene trabaho para con migo. Later on I learned that she had been sending my college dormitory letters with attached clippings of her wildlife photography years after I had already graduated from the university. Perhaps in her mind, I had always been that cosmopolitan college girl who was forever trapped in that cozy university life. The dormitory manager, I suppose after having had enough of her flood of mails, found a way to connect the two of us and even forwarded all the unopened letters she had sent. In her latest letter, she wrote that she had just returned from a trip to one of the remote islands down south. She didn’t specify if it was Tawi-Tawi or Sulu, but she said that she seemed to have caught a rather strange affliction. She thought it was silly, but she was only following the doctor’s order to find someone to help care for her until this mysterious affliction passed. She said that there were days when she was just awake for four hours, so she was messing up on the medication schedule a lot. She said, would I be kind enough to help her out just until she got better? Señor, el di mio corazon! I left Dumaguete that night, and boarded a ferry to Zamboanga.

Surprisingly, my sister was up on her feet the moment she heard me knock on the gate. Back in our childhood home, she greeted me with air-kisses on both cheeks, and I remember thinking how she smelled like loam and rain. Her dark black hair was thinning out but it cascaded past her waist, and she wore nothing but a malong asymmetrically tied around her shoulder. I fit into her life with ease, into this barely furnished bungalow that somehow suddenly felt too small. She ushered me to our parents’ bedroom, which she had now converted into a darkroom. She smiled tentatively and admitted that this was where she spent most of her waking hours, hunched over trays and bathed in red light. Film developers, stop bath, fixer. Todo aqui, she lined rows and rows of unreleased photos from all her past trips, clothespinned onto whatever objects would hold them.

Her illness had this way of enforcing intimacy between us, so for several weeks we were like two creatures carefully orbiting each other, mentally calculating just how much distance we could cover to get as close to one another. The years of estrangement were there, but she brushed off our differences as though nothing but fruit flies—bothersome things but, really, little nothings. Si nohay tu hermana, gendeh tu entiende. On rare occasions when she had enough energy to walk, we would venture out as far as Pasonanca Park, where she could inhale greedy lungfuls of fresh mountain air. Sabe tu, kame el primero plantitas. Sometimes, we would pick beautiful wild flowers that caught her fancy and transplant them back home. When the succeeding hospital appointments continued to prove futile, she asked me to bring more potted flowers and plants at home, she needed the outdoors indoors, she told me.

She asked for more fresh cuttings the remaining weeks: climbing pandan, brilliant red begonia, violet and yellow orchids, orange bougainvillea, and young ferns with fiddleheads—an array of wildflowers in loud colors against broad green leaves. Once, she told me how Zamboanga derived its name from the Malay word jambangan, which meant a place of flowers. Then she would ask me to get her a humidifier and sunlamps on timer, so her little jambangan inside our home could flourish. De locuras, I see you thinking, but these were the only things she wanted to do. By then she had given up all medical treatments… and bathing. Let me tell you—the musky scent that emanated inside was not entirely due to that little jungle of hers alone! She would recoil at any suggestion to rest or wash herself up, and those were really ugly moments I’d rather not revisit.

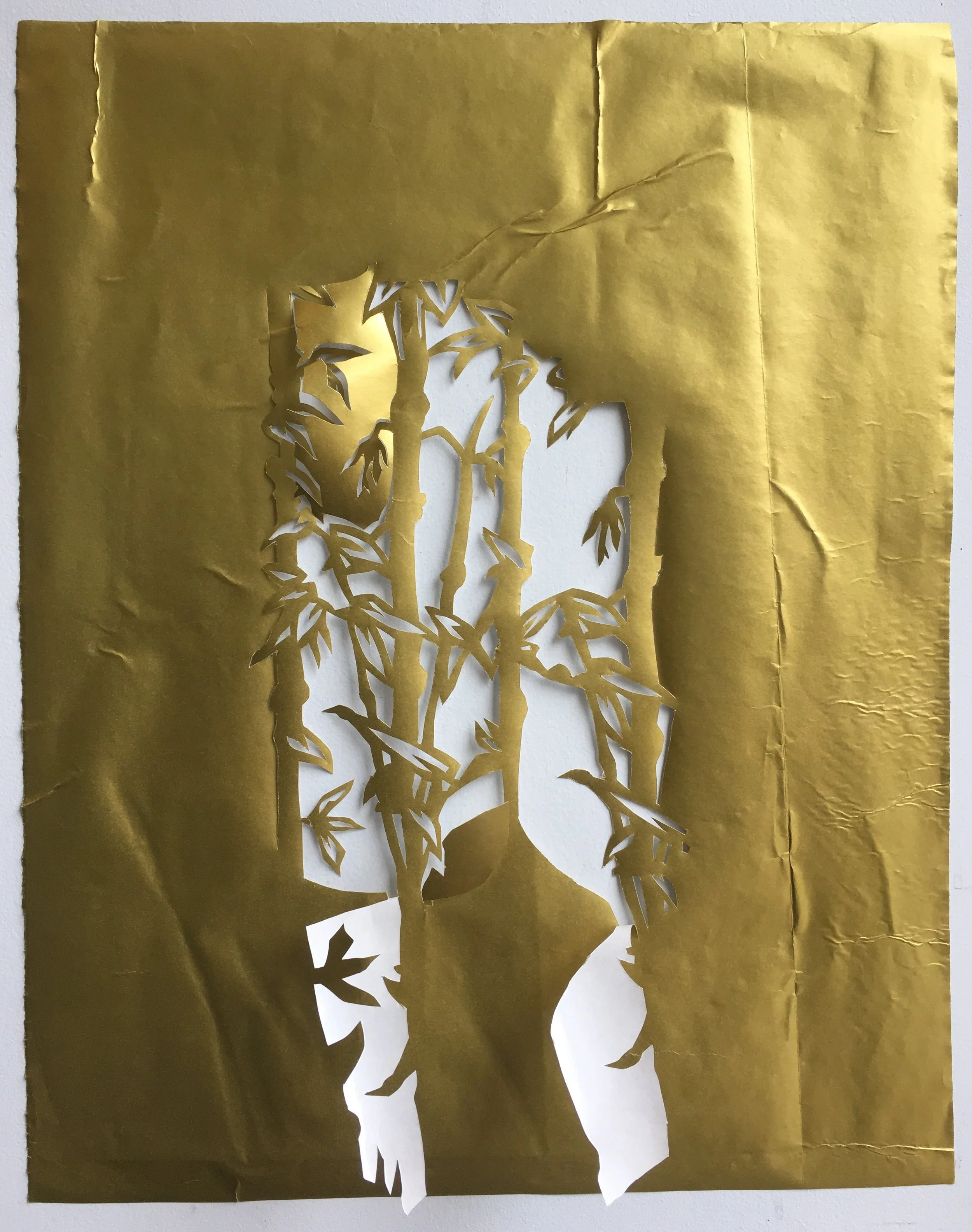

Neil Pasilan - Isla Hubad (2012), Mixed Media on canvas

Image description: A yellowish-green painting of a nude woman lying sideways in a colorful field of flowers. Several faceless figures stand behind her. Light blue mountains can also be seen in the background on the horizon.

It was around the time her hair fell out that she requested more soil. Sacks and sacks of loam soil. The few hours when she remained conscious, she tiptoed about her jungle darkroom, strands of hair falling everywhere as though an animal was shedding fur. The first five sacks I had bought, she scattered around the floor. Then, I kid you not, a layer of organic compost. The topmost layer was a mixture of loamy and silty soil. She was hardly awake the next few days, and in the rare moments when she was, she would just lie on her cushion of earth and browse through the photographs she had taken. We sat together in the dark, in total silence save for the constant humming of the humidifier, and just smelled the deep rainforest scent of the room. On her last night, she asked me to put more soil over there, right where the bougainvillea made an arc, where she decided would be her final bed. She had asked me to cover her body with soil—numa mira ansina comigo—except for her face. I obliged, of course. A serene smile was plastered across her face and I watched her breath go heavy and slow until she was breathing no more.

I fell asleep there in the dirt, beside my sister. I remember expecting a lone magical flower to sprout where my sister had passed, and of course I would name the flower after her. But there was none. This isn’t a fairytale, after all. I grope for my sister’s remains, but there was none either. I scrambled for the windows, the door, anything to get me out of this utter darkness. A striking dart of light, true daylight, pierced through the room. It fell across the rain-forest darkroom, splashing the wild bloom of flowers with a blinding yellow glow.

And so here I am, as you find me today, un loca vieja with her assortment of flowers and plants. My neighbors are kind and regularly check up on me, but I know that behind my back they talk about me in hushed, pitiful tones. I don’t really mind. My sister, she told me, that it was the rich profusion of flowers that made the first navigators settle in old Zamboanga. I fancy myself some sort of a navigator, and I understand very well their reason for choosing to stay. Have you ever woken up to the sheer magnificence of a birdsong? Or spend the day simply mesmerized by the way the pinkish-purple vines refuse to follow any pattern? Outside the city pulsates with fast-paced life; in here, I am cocooned in this rainforest room. Soon, I know, I too shall take my rest. And I would leave as my sister did, con este tierra, where it smells faintly of my sister’s hair and the sweet tang of freshly turned soil.

“This is: Zamboangan” by Al Amin Films

Sigrid Marianne Gayangos was born and raised in Zamboanga City, Philippines. Her works have appeared in various venues such as Cha: An Asian Literary Journal, OMBAK Southeast Asia's Weird Fiction Journal, ANMLY, Likhaan Journal, Everything Change: An Anthology of Climate Fiction and Reckoning Magazine, among others. Her debut collection of short stories, Laut, is forthcoming from the University of the Philippines Press.

*

Neil Pasilan is a self-taught artist who hails from Bacolod City. He started making art as a young man, when he would spend his days sculpting figures out of discarded clay. He would have daily “exhibits” with his neighbor, with only themselves as their viewers and grandmothers yelling in the background. This love for art, as well as its more existential offerings, is deeply rooted in the artist who moved to Manila and survived by selling crafts and products that he would make by hand. Twenty years later, Pasilan focuses on painting and mixed media works, but still cannot seem to exorcise his affinity for terra cotta.

If you’ve enjoyed reading this article, please consider making a donation. Your donation goes towards paying our contributors and a modest stipend to our editors. Singapore Unbound is powered by volunteers, and we depend on individual supporters. To maintain our independence, we do not seek or accept direct funding from any government.

‘But later… we didn’t talk about love. We talk about the land and its people.’ – a short story by Kaushik Ranjan Bora, translated from the Assamese by Aruni Kashyap.