Dreamlapse

By Monica Kim

-

Sexual Assault

When you dream, how do you know you’re in your own body? Does your mind take you down paths you don’t recognize, does it create shadowy figures in the periphery of your vision, does it hurt when you jerk awake and hit your head against the slanted ceiling of your bedroom?

What I mean to say is, do you remember your dreams; do you inhabit your dreams; do you become your dreams; do your dreams represent someone else from the past?

The diary is falling apart. If I don’t tie it together with a rubber band, it’ll separate, the cover and pages coming cleanly off the spine.

I open to the middle of a random page and bring my face against the paper, breathing as if I could absorb the words with my nose––it’s musty, and there’s something faint there, that old paper smell.

When I look at the page, at twelve-year-old me’s handwriting, the lead slightly smudged against lined paper, I want to bring her back––not that I want to be her again––but it feels like there should be a recognition in my writing, in these pages, in my memories. Yet all I am is in the dark, empty room of my childhood, in the house of my upbringing, the place my parents are finally abandoning.

I flip to the next page. Today I dreamt …

May 7 2010

● fabric? blanket? under me

● 5? 10? 15? men w/ same haircut

○ they looked like… maybe military?

○ i dont remember

● dr. moon said it was ok if i couldnt remember everything + it was nice of him to say that but i dont rlly like him

● sometimes i think he stands too close to me

Dr. Moon. I remember him. I only went into his office for a few months, after convincing my mom that I wasn’t having any more dreams (a lie) and that anyways, his treatments weren’t working (a truth).

● all the men wear the same clothes

● 1 woman

○ shes lying next to me? (but “me” isnt actually “me.” idk how old “me” in my dream is but her body is skinnier than me + she has longer hair + shes kind of dirty like she hasnt taken a shower in days. idk her name but her name isnt mine. idk…)

Even reading this, ten years later, with what I know now, it’s still confusing to me. How could I have been dreaming of someone, inhabiting someone’s body, who wasn’t me, but who was real? Whose name I didn’t know, still don’t know, but has to be real?

In my last year of undergrad, we read Make It Scream, Make It Burn by Leslie Jamison and even though I’d skimmed most of the book––not because I didn’t like it, but because I had a million other readings for other classes plus graduation plus the stressful uncertainty of my future plus juggling a job––one chapter stuck out to me, still sticks out to me now, and that was the only chapter I read with such detail and care that I underlined almost every sentence.

The story comes back to me now: in “We Tell Ourselves Stories in Order to Live Again,” there was a boy named James who has dreams from the memories of a World War II soldier. He knows his name, his fellow soldiers’ names, even the plane the soldier flew in. How could a teenager know such details so specifically, without ever having read about the soldier before? James never wanted to be a soldier, had never been interested in World War II before these dreams.

I never learned about the Japanese atrocities against Korean women in World War II until college. And I would never, ever want to inhabit the body of the girl in my dreams.

● red mark on left side of her face

● feels like red mark on my (but not my) face

I flip the diary pages to a few months back. My fingers twitch, and I resist the urge to read in a linear fashion.

After all, aren’t dreams and memories cyclical?

Feb 2 2010

● its weird starting my diary again, but only for my dreams

● i stopped writing when i started 6th gr last yr since no one would think im cool but dr. moon (new dr. – mom + dad finally decided to take me since i was still having those weird dreams even after they sprayed holy water on my pillow. not that i rlly believed that would work…) said it might help to write my dreams down

● ok my dream… no one is gonna find these one day + read them, right?

No one except twelve-year-old me and current, twenty-two-year-old me.

● only thing i remember from last night (early this morning?) were hands

○ dont think they were my (the girl’s) hands bc they were bigger + they had lots of callouses

● dream shifted to woman giving birth to baby, baby that wasnt me (the girl)

So much of it is coming back to me now. Dreams of a policeman telling me––the girl whose body I was in––about work in a factory in Japan, how so many girls like me left Korea for good, honest work, to help our struggling families. Dreams of my mother and father and my baby brother lying together on the floor, huddled for warmth as the wind whipped outside. Whispers between my parents about what they should do; silent arguments and agreements about what I could do. Dreams of me hugging my family goodbye, resolutely dry-eyed as I left home, found the policeman, who transferred me and other girls my age and younger and older––but not much older––to Japanese soldiers, who looked at us in a way that made my skin crawl, who looked at us, my heart immediately dropping, wondering if, after all, those rumors had been true. Dreams of dark spaces, dreams of being blindfolded, dreams of not knowing where I was, dreams of waking up in a room with five other women, our bodies immobile, our cries silent. Dreams of a rough hand grabbing my wrist, of multiple men surrounding me, all Japanese soldiers, of passing out and waking up with a terrible pain in between my legs. Dreams of combing another woman’s hair, of tending to the bruises and cut lips and internal injuries no one could see, of removing the crab lice from my friend’s pubic hair. Dreams of writing a letter to my father and mother and baby brother, no longer a baby, a letter none of them would receive. Dreams of the letter burning and the fire colliding with my skin. Dreams of winters where the snow reached my knees. Dreams of summers where sweat stuck to every crevice of my body. All in this unbearable little room. Dreams of soldiers leaving, of whispers about the war ending, of the little blossom of hope opening inside me.

Eunjin Kim - Seelenraum (Soul space 1), 2015, pigments and acrylic on canvas, 60x80cm

Image description: A surrealist painting in white, pink, green, and dark-blue hues of a woman embracing a glowing, wispy, shapeless, white figure.

Oct 29 2010

● ik im supposed to be writing abt my dreams but im so angry abt what happened @ school today i have to write abt this instead

● we were learning abt sex (ew) + i asked a few qs bc i wanted to know if this is what was happening in my dreams but chris kept making fun of me + laughing + asked if i rlly wanted to do it so much, why didnt i just ask any boy in the room, except oh, no one would want me because im chinese

The first time I met Chris, we had been assigned seats next to each other in homeroom. On the first day of sixth grade, when I sat down next to him, he turned toward me. When he opened his mouth, I thought he might say hello, but instead he said, loud enough for the rest of the class to hear, “Chinese commie!” and pointed finger guns at me, pew pew.

I glared at him. “I’m Korean.”

He stared at me, then pulled out the finger guns again. “North Korean commie!” Pew pew.

I remember digging my fingernails so deeply into the palms of my hands, wanting to punch him so bad, knowing I’d get in trouble if I did. I was so angry that no one bothered to distinguish between Chinese and Korean, and yet today I’m sitting with the fact that although the Japanese military sexually enslaved Korean women and girls, they had also raped and sexually enslaved women and girls from China, Taiwan, the Philippines, Indonesia, East Timor, the Netherlands, Malaysia…

In the end, you were just another body to wreak violence unto.

● i told him for the millionth time that im korean + i didnt want to do ‘it’ w/ anyone + just leave me the fuck alone then everyone made a big deal of me saying fuck + ms. friedman (FUCK HER) pulled me aside to give me a warning then apologize to chris + that i shouldnt ask “inappropriate questions”

● ugggghhhh. he can go rot in hell

● felt like crying before but now im just angry. i HATE this school.

I hated school then, feeling so out of place, being one of the only few Asians in my middle-school and high-school years. And yet––it was through school that I first learned about those women, in my college years. Through school I took an international feminism class, through school I learned about the survivors who protested outside of the Japanese embassy in Seoul every Wednesday, through school I learned about the kid who had strange dreams like mine.

June 14 2011

● 1st time i havent had dream in over 1 yr. THE !!! FIRST !!! TIME !!!

● no soldiers. no girls

○ no blankets no bruises no guns no small room no letters

● N O T H I N G

● feels so good to dream of nothing

I close the diary, leaning back against the wall of my old bedroom. I close my eyes.

Coincidentally (although I’m beginning to think not so coincidentally) this last diary entry was from my first trip to South Korea. My parents and I flew to Daegu, to visit my grandfather’s new burial site.

The Korean summer hadn’t become too unbearably humid yet, but I felt hyper-aware of strangers’ eyes on me, lingering over my shorts and tank top. Mom gave me a sweater to cover my shoulders, but the fabric felt too itchy against my skin. People could stare at me all they wanted under the cover of their umbrellas, hiding themselves from the strength of the sun.

When we reached my grandfather’s burial site, my parents knelt on their knees and murmured prayers in Korean, making a sign of the cross over themselves and over the framed photograph of my grandfather. They offered a pear, dried fish, and jeon for his soul.

I hate to admit it, but I zoned out while they were doing this. My grandfather passed away when I was two years old; I had barely any memory of him. The only way I knew him was through photographs and my dad’s very few anecdotes. My mind wandered, and my eyes fell over the other burial sites, the other families kneeling and praying next to us.

How many of these people had been alive during the Korean War, during Japanese colonization? How many had felt a gun to the back of their heads, pressed there by American soldiers who mistook them for communists? How many women laid here, and were any of these women the women like the girl I inhabited in my dreams?

A shudder came over me, and I felt a tightness in my chest, something that stretched deep into the very ends of my bones. All of a sudden, I felt like I wanted to cry––to let out a wail, to pound my fists against the grass and to curl into a fetal position. My grandfather had been alive during Japanese colonization, during World War II, during the Korean War––he had survived it all. But did he have any sisters? Mothers? Aunts? Were any of them taken away? Did he and his family have to cross over the newly made, arbitrarily drawn border, to the same land that was now called a different country? Did he have to leave any of his family behind––grandparents, small children, disabled siblings––because they were seen as weak, because they thought they wouldn’t be able to make it? Who did he lose?

“Mi-Young.” Out of nowhere, my mother’s voice came to me. She motioned for me to kneel, to join her and my father in prayer.

I did as I was told, my knees feeling warm against the summer ground. I didn’t have the words for prayer, at least not for my grandfather. But I pictured the young girl of my dreams. In that moment, I called her Jae-Young, after my grandmother’s sister, who died during the war.

Jae-Young. Did you ever make it home? When you closed your eyes, were you able to see the mountains and rolling hills of your homeland? I don’t know if you ever made it back. But I am here. I am home.

I tuck the journal underneath my arm, bound down the stairs, past the living room that is empty save for a few boxes, out the door, and sit on the front steps, breathing in the summer rain. My parents are coming to gather the rest of the boxes soon––I had asked them for some time alone to say goodbye to this childhood home. The young girl I dreamt of––the young girl I named Jae-Young, briefly, in Daegu––comes back to me. Dragon eyes, middle-parted, coarse, black hair, rounded cheeks.

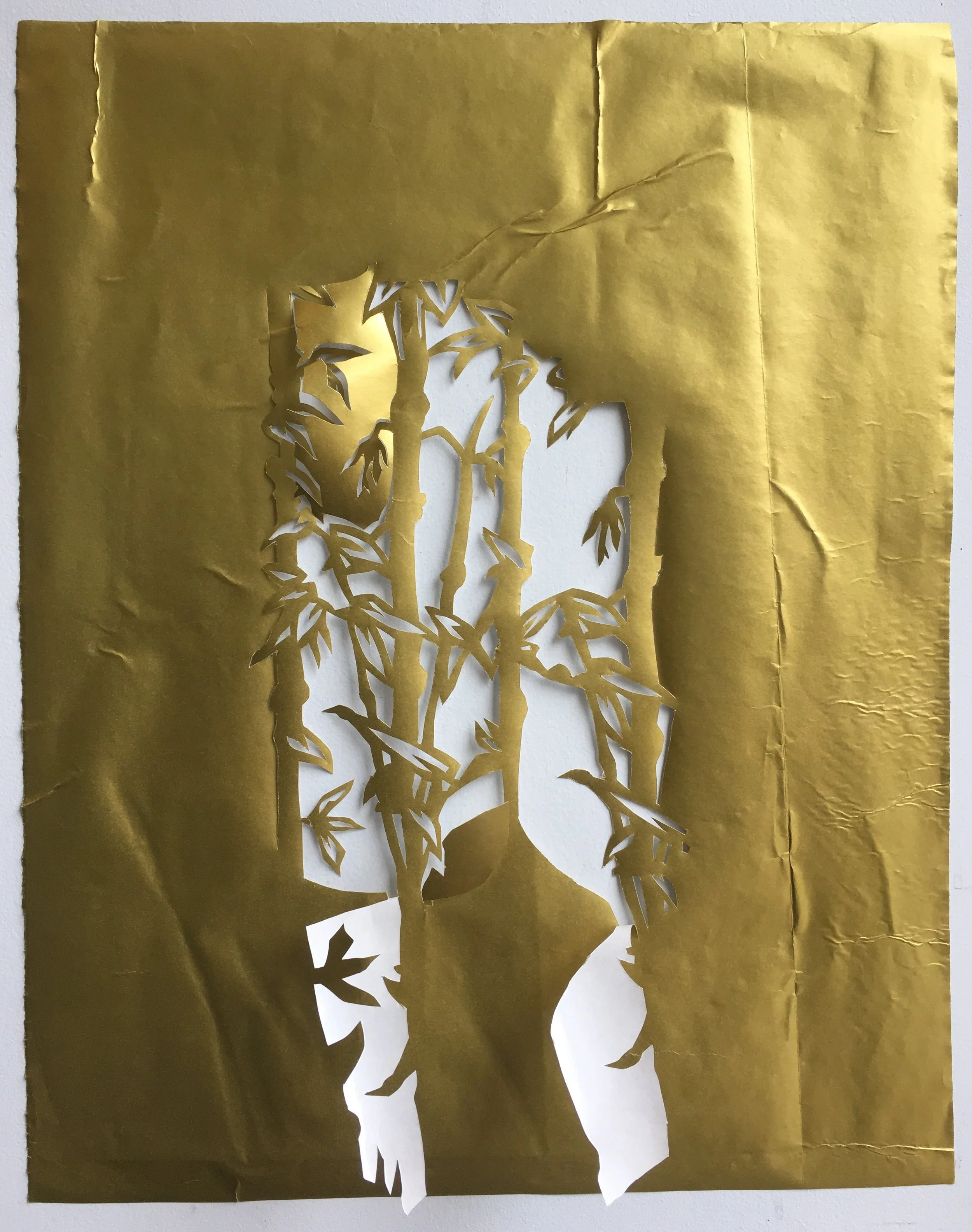

Eunjin Kim - Seelenraum (Soul space 2), 2015, pigments and acrylic on paper, 70x100cm

Image description: A surrealist painting of a vague outline of two embracing figures against a dark navy-blue background.

I can’t say for certain if my return to South Korea all those years ago meant Jae-Young’s homecoming, too, and if the return of her soul to her homeland meant her soul leaving my dreams, leaving my subconscious. The timing seems too coincidental, and yet––I remember that boy, James, was only able to stop dreaming from the soldier’s body after he and his parents went to Japan and set out on a boat in the middle of the Pacific Ocean, bursting into tears, holding each other as the boat rocked amidst the waves.

“Jae-Young,” I whisper out loud, and then I clear my throat, open my mouth wider. “Jae-Young.” I don’t know if that is your actual name; it feels wrong to misname you, but it feels even more wrong to not give you a name at all.

“Jae-Young.” Louder. Louder. Louder, still, and then I’m running back into the house, returning to the spot in the living room where we did jesa, where we honored my male ancestors on my father’s side. I never understood why we only offered food to the men in my father’s line, and never the women or the ancestors on my mother’s side. When I asked my parents about this once, they mumbled something about tradition or culture.

Perhaps what I’m about to do is sacrilege. But my hands move of their own accord, placing the diary in the middle of the dusty floor, as if it were a table replete with a feast.

I bring my hands in front of me and bow to my knees, my forehead kissing the dusty wooden floorboard. I bow, again. I stand, and I bow, my back perpendicular to the floor. An offering.

“Jae-Young,” I say, out loud, my voice echoing in the room full of ghosts of the past. I cough, clearing my throat again. It feels awkward to do this, but I can’t stop. I say the names of some of the halmeoni we know:

Kim Hak-Sun

Yun Tu-Ri

Kim Kayako

Pak Ok-Nyon

Kim Young-Im

Mun P’il-Gi

Hwang Kum-Ju

Lee Ok-Seon

Gil Won-Ok

Pak Ok-Sun

Kang Soon-Shim

Lee Young-Ok

Kim Eun-Rye

Kim Gun-Ja

Mun Ok-Ju

Lee Ji-Sook

Kim Bok-Dong

Kim Han-Soon

Kang Duk-Kyung

Lee Yong-Su

The list is incomplete.

Eunjin Kim - Selbstporträt (Self portrait), 2014, etching, each 5x10cm

Image description: Four self-portrait images of a woman fixing her hair with one hand and enlarging one eye with another hand. Each portrait is etched on a piece of paper, and progressively they have more details and shadows.

I stand up straight again, moving my body side to side. I brush the dust off my knees, grab the diary, look around the living room once more, and before my parents can find me here and wonder what I’m doing standing alone in this haunted room, I leave for my spot on the front door steps again.

Jae-Young, it feels wrong to not give you a face, a story. There are so many women, halmeoni, like you, who have not been able to return home. Some may have received money but no one’s received an apology, recognition from the Japanese government. Not even a court in South Korea pins the violence onto Japan. Not even some historians in America recognize this violence.

Something blooms in my chest, the same emotion I’d felt all those years ago in Daegu.

Han.

There are more of you dying. Only a few are left, to impart your memories and experiences to us, to remember the pain that wreaked havoc against your bodies and your minds and your souls. It feels like time is slipping away from us, that your wrinkled hands and crooked teeth and moles scattered across your bodies like constellations are moving farther and farther away from us, one foot slowly inching towards the other side. When you leave, I hope we don’t forget you. When you leave, I hope this never happens again.

One day, I hope you’ll find peace.[1]

Endnotes

[1] Learn more about the women sexually enslaved by the Japanese military during World War II, euphemistically called “comfort women”: https://comfortwomenaction.carrd.co/

Monica Kim is a queer writer and organizer. Born in South Korea, she now lives in Brooklyn, New York. She won the inaugural Jane Kenyon Chapbook Prize Award in 2020 and The Blue Mountain Review Asian American Chapbook Award in 2021. Her writing has been published in A Velvet Giant, Call Me [Brackets], Pollux Journal, and others, and is forthcoming in Anthropocene, Honey Literary, and SUSPECT. You can find her on Twitter at @kimmonjoo.

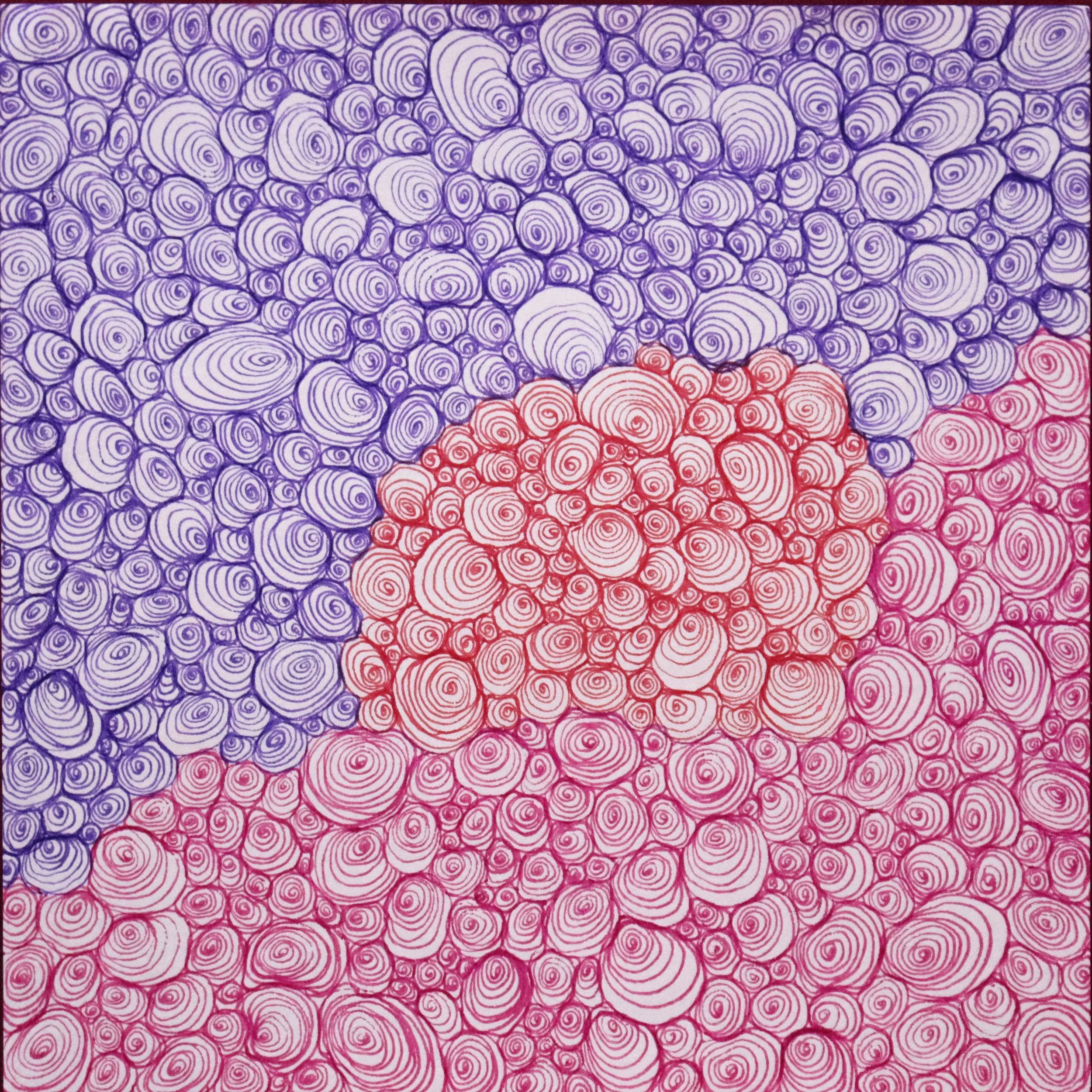

With her works, Eunjin Kim wants to make the invisible visible. She is currently working in as “semi-abstract lyrical expressionism”. With colors, lines and textures she wants to explore the peculiarities of people and the world in which they live. Her sources of inspiration are people and nature. The painter is constantly on the way. Eunjin Kim was born in Busan, Korea. She studied Korean language and literature as well as industrial design. After a long working phase as a graphic designer, she studied at the Visual Art School Basel. Today she works in Switzerland.

If you’ve enjoyed reading this article, please consider making a donation. Your donation goes towards paying our contributors and a modest stipend to our editors. Singapore Unbound is powered by volunteers, and we depend on individual supporters. To maintain our independence, we do not seek or accept direct funding from any government.

‘But later… we didn’t talk about love. We talk about the land and its people.’ – a short story by Kaushik Ranjan Bora, translated from the Assamese by Aruni Kashyap.