#YISHREADS January 2023

By Ng Yi-Sheng / @yishkabob

It’s a new year, which means a whole new universe of books to read and review! But rather than leave the books of 2022 behind, I’m using January as a catch-up month, dedicated to mind-expanding works I never got round to featuring in my column—specifically in the genre of non-fiction prose.

Among my selections, there’s a mid-century Martinican decolonial treatise (jumping the gun for Black History Month in February!), a landmark collection of essays by Singaporean Indian feminists, an international perspective on sex workers’ rights, a history of South India and a psychiatric analysis of PTSD. A mixed bag, maybe, but now I’ve put them all in a row, I see some common themes: oppression, identity formation, struggle and liberation. No escaping the personal/political in this journal!

Discourse on Colonialism, by Aimé Césaire

Translated by Joan Pinkham

Monthly Review Press, 2001

This here's a 1950 pamphlet-length essay by the founder of the pan-African cultural movement Négritude! And again, this is one of those texts I wish I'd read when I was doing my thesis. Even though it was written so early, before most nations around us *had* declared independence from European powers, it's still powerful and resonant, interrogating the salvationist, civilisational ideology of colonialism (even holding Japan to account for doing the same thing); noting the complicity of comprador elites and feudal lords in colonised nations and liberal bourgeois in colonising nations (it's not just the extraction of resources, but the everyday participation of settlers that makes colonialism); even refusing a turn-back-the-clock strategy of decolonisation, noting that colonisation had disrupted cultures' independent progress towards their own more democratic futures.

The biggest theme, perhaps, is how colonisation isn't just bad for the colonised, but also the coloniser. “Europe is indefensible!”, he declares. Everyone in France hates Hitler now, but what he did in Europe is just a logical extension of what Europe did to the rest of the world. Boomerang effect, we said in the discussion.

All this written in gloriously poetic prose, still stunning after translation—Robin D. G. Kelley explains in his intro, "The Poetics of Anticolonialism" how Césaire's Négritude was a political movement (Marxist, specifically) as much as it was surrealist, and how French thinkers of the period drew liberally from both spheres of arts and politics. Activism needs more poets, methinks.

And also the niggling question of why, when such an important work has existed for 70 years, we haven't been referencing it in Singaporean arts and thought? Sure, it was in French, but come on, loads of our intellectuals have studied the language too. The dominance of the Anglophone tradition ends up gatekeeping even other European languages

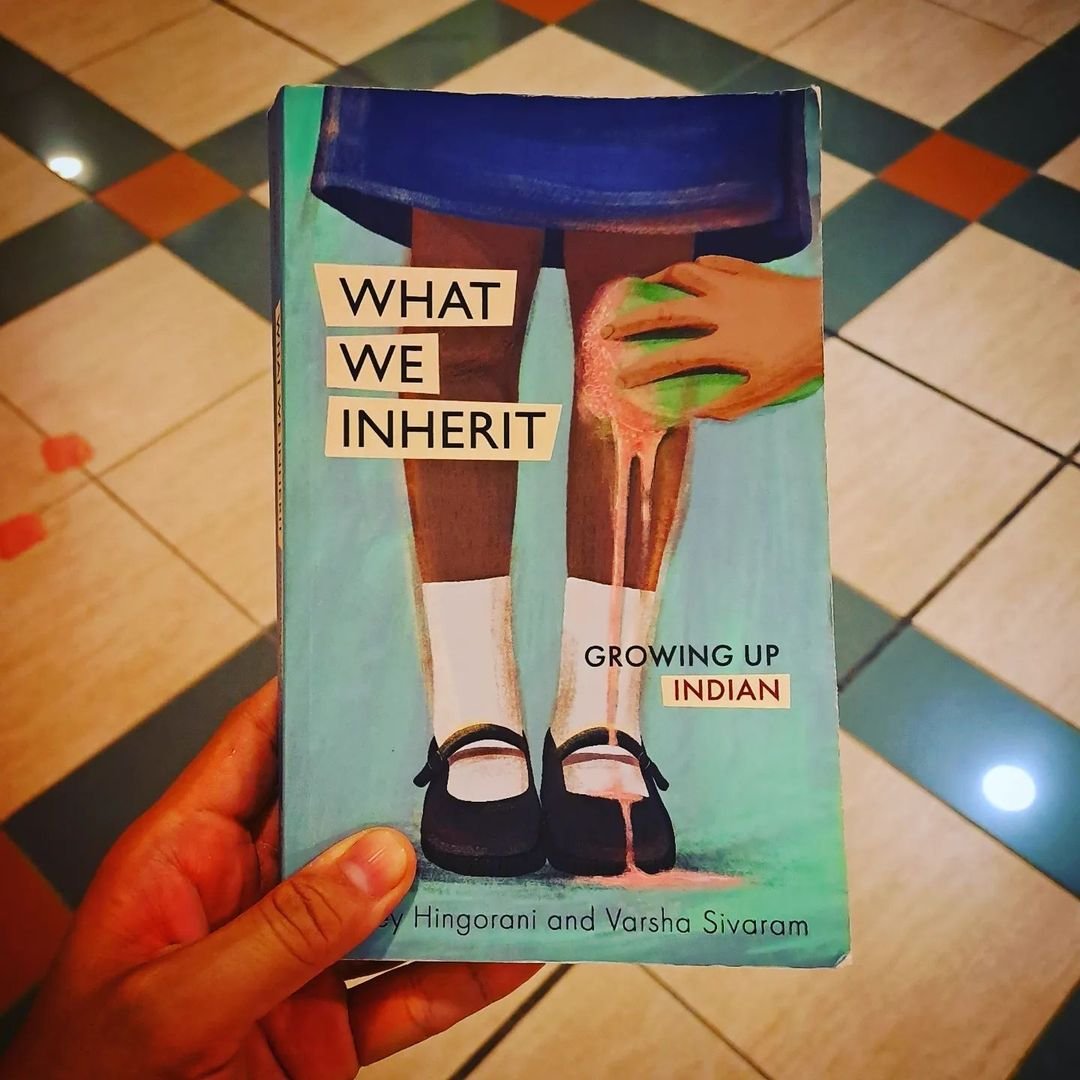

What We Inherit: Growing Up Indian, eds. Shailey Hingorani and Varsha Sivaram

AWARE, 2022

This is AWARE’s follow-up to their two-volume series of Malay women’s non-fiction writings, Growing Up Perempuan, and it’s well worth a read—partly cos they seem to have approached already published English language writers to share their stories, which means the stories are mostly finely crafted works of prose. (Mind you, I’ve heard some critics argue this makes the project way less democratic.)

The more obvious reason for picking this up, of course, is because of its contents: 40 essays and poems (I’m counting the intro and preface here) about the challenges of being an Indian woman in SG, covering a broad swathe of perspectives—there are Tamils, Malayalees, Gujaratis, Punjabis, Chitty Melaka and Chindians; Hindus, Muslims, Christians and Sikhs; immigrants and emigrants; queer women and straight women (no trans women, surprisingly!)—even three men, which is, um, a choice, even though Jaryl George Solomon’s story of brutal racism in the gay male community is fearsomely familiar. And because no-one has to speak as the single voice representing all Indian Singaporeans, a lot of dirty laundry gets aired: not just the microaggressions and holy-sh*t-macroaggressions of Chinese Singaporeans, but the fearsome violence of patriarchs, the viciousness and narrow-mindedness of matriarchs, the struggles of identifying with any one culture, especially due to language attrition (both my friends Prasanthi Ram and Balli Kaur Jaswal weigh in here, respectively speaking about the guilt of Mandarin acquisition and the joy of Punjabi rediscovery), the horribleness of fellow schoolgirls who mock coconut oil in curly hair and melanin (the cover image comes from the story of a classmate who would pretend to wash the darkness from the author’s knees).

Yet that freedom from tokenism also means some writers tell surprising tales of positivity: Anisha Rahlan on how the Cards Against Humanity rip-off game Limpeh Says became her ticket into Singaporean acceptance; Pooja Nansi on how her immigrant mum held “kitty parties” with other Gujarati women to create community in a new country; Leia Devadason on finding affirmation through traditional dance—only to have it snatched away on the discovery of her teacher’s homophobia.

Quite wonderfully complex and beautifully told… plus, there’s a collective family photo album at the back!

Revolting Prostitutes: The Fight for Sex Workers' Rights, by Molly Smith and Juno Mac

Verso, 2018

This here’s a book-length political manifesto, written by two British sex workers—another one of those genuinely mind-opening non-fic works that makes you look at an issue in a way you've never done before.

Now, I've always been pretty OK with the notion of sex work—my dad was 100% open about how he and my mum used to go for dates in Bugis Street. But this book makes me realise my opinion's been coloured by patriarchal notions of it being a necessary evil (“the virtue of the monde is assured by the demi-monde,” as an 1897 article puts it) and by the 2000s wave of sex-positive feminists who gave talks at Barnard College, asserting that sex work can be empowering.

The authors aren't, in fact, very interested in discussions about bodily autonomy and social stigma. Prostitution's been invoked way too much as a symbol, they say, w/o looking at the lives of actual people doing sex work. What they want to talk about is workers' rights: i.e. the fact that most sex workers are in the business because they desperately need the $$$, and there's not a lot of better options for them.

So any policy that polices them—whether through full criminalisation in the US, limited legalisation in the Netherlands (or indeed Singapore), or punishing only johns and pimps in Sweden (i.e. the Nordic model) ends up causing harm, forcing sex workers to rely on pimps or more dangerous clients, often leaving them unable to report violence and theft to the police—often, in fact, being robbed by the police, who pocket their earnings while claiming to be rescuing them from vice! (The stories of injustice and abuse of specific sex workers are endless and heartbreaking.)

What does seem to help is the New Zealand model of decriminalisation, coded into law in 2003 thanks to the campaigning of the New Zealand Collective of Prostitutes and the work of MP Georgina Beyer, a Maori trans woman who was a former street-based sex worker. Streetwalkers can now work in well-lit streets without bother and even report their managers for sexual harassment! And no, there was no boom in sex work after its enactment—there are even provisions for allowing workers leaving the trade to immediately access their social security.

But one big gap in the New Zealand model—and a huge problem in all developed nations—is the enforcement of borders. Migrant sex workers are treated with horrible cruelty, deported summarily, w/o recourse to rights. and because the authors don't shy away from the issue of trafficking, which others have argued isn't sex work (since anti-sex work feminists keep using it as a reason for crackdowns). Traffickers don't kidnap randos; they prey on women who already want to migrate, and tougher border laws just make the $$$ they charge for migrants more exorbitant and their treatment more ruthless. So Smith and Mac call for complete abolition of border laws—no human is illegal, people should be able to work where they want, and if everyone had free movement, traffickers would have no power over migrants.

Singapore is never mentioned in the book, which is a shame: we've got a weird situation of regulationism where sex work is technically legal but soliciting isn't, so brothels still suffer horrific raids. Plus, the dependence on migrant women as sex workers (supposedly illegal, but folks at Project X have told me they've seen these women with work visas) means that it's harder to build a community of Singaporean sex worker activists who could take the government to task. Not impossible, though, since a lot of our trans sex workers are local!

One blessing, however, is that (afaik) mainstream Singaporean feminist activism is not anti-sex work, unlike in much of the West—the authors cite the horrifyingly cruel words of feminist leaders in these nations, who refuse solidarity with sex workers, often cos they're so distanced from the working class that they think these women can easily leave the industry and find other jobs. Sure, many of our women leaders may be antis (President Halimah Yaacob once pledged to “clean up” Woodlands Town Garden), but the sheer difficulty of being an activist here may have winnowed the secret conservatives out of AWARE.

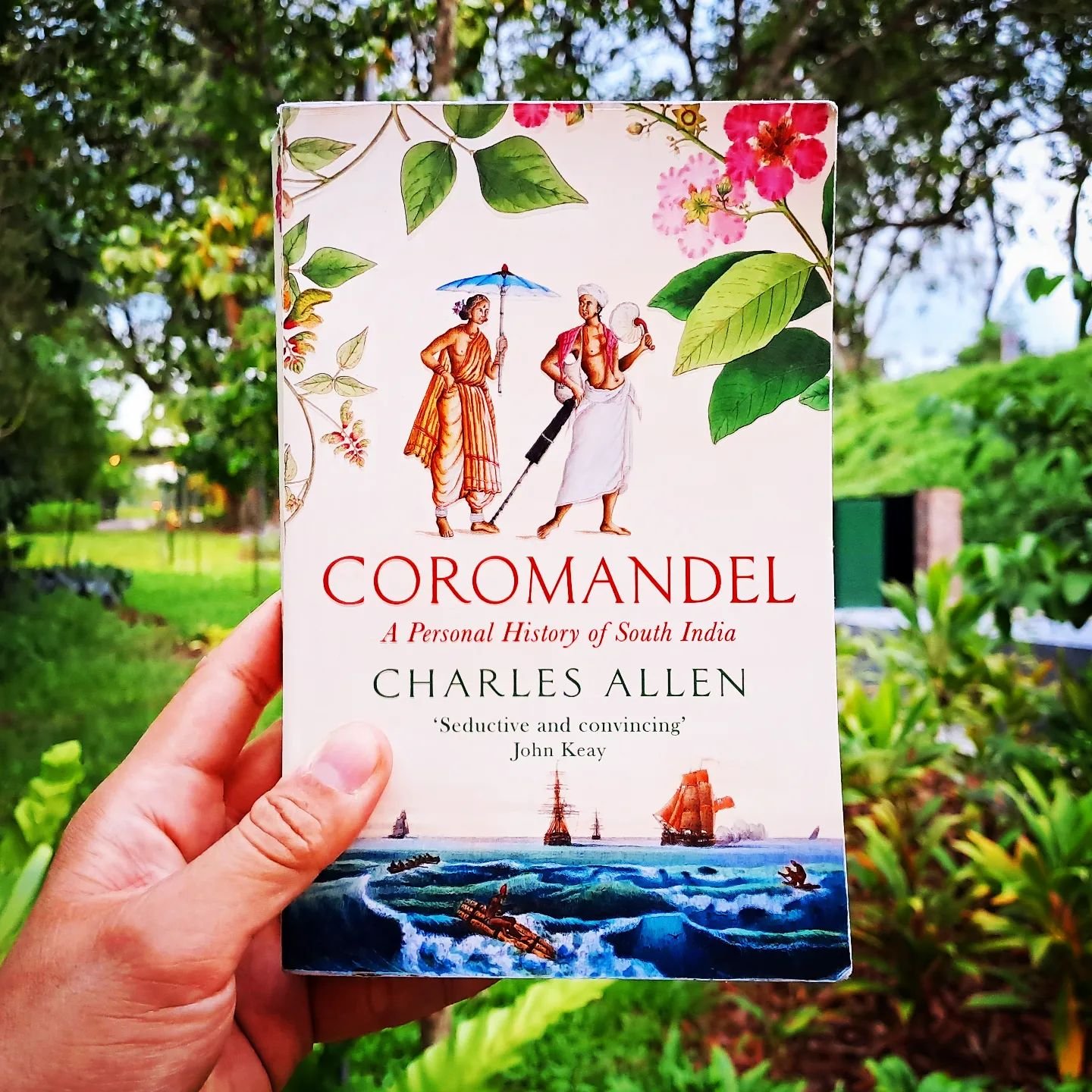

Coromandel: A Personal History of South India, by Charles Allen

Little, Brown, 2017

The early chapters of this work are riveting: autobiographical recollections of a childhood in the last days of the British Raj; revelations about neolithic history as determined by haplogroups and geographical features which turn out to be millennia-old accretions of nomads' burnt cowdung; close readings of Vedic texts that reveal the history of the Aryan invasion and the Dravidian flight southwards: the Saraswati, the holiest of the seven sacred rivers, may in fact be the Harut in Afghanistan, with later Puranic legends concocted to explain its disappearance.

Later chapters are fascinating if a little confusing, with chronology stumbling over the rise and fall of multiple trends—conflicting myths of Agastya bringing either Sanskrit or Tamil past the Vindhya Mountain Range; the forgotten dominance of Jains and Buddhists in the South (e.g. Prince Ilango and the sage Nagarjuna—Allen argues that the infamous Jaganath chariot, which gave rise to the word juggernaut, was in fact based on Buddhist relic processions); the reigns of Satyavahanas and Cholas and Nambudiri Brahmins and Nairs and Sultans and the East India Company.

Part of the complication lies in the fact that he's telling at least two stories every time: what happened in the past and also how it was discovered, often thanks to British colonial researchers and their native informants. He's smart about affirming that colonisation was v bad for India, but repeatedly notes how it was responsible for the recovery and dissemination of knowledge across lines of religion and caste (the Brahmins invented calculus and then kept it to themselves for centuries! —and how, in the post-truth Hindutva age, this commitment to secular objectivity that many independence fighters relied upon is now being jettisoned in favour of mad, murderous myth.

One thing I must treasure, however, is the surplus of stories that helps me contextualise our region's South Indian heritage, from the poetry of Thiruvalluvar to the voyages of Bodhidharma to the anti-casteist revolutions of Periyar. So many female figures too: the goddess Devi Kanyakumari who gave her name to Cape Comorin; the warrior princess Meenakshi of Madurai who had three breasts until she beheld Shiva; the 10th C Chola Queen Sembiyan Mayadevi, builder of temples and model for bronzes; the 19th C Rani Gowri Lakshmj Bayi, puppet Queen of Travancore; and a commoner too: Nangeli wife of Chirukandan, who launched a revolution by (CW: GORE) presenting a tax collector with her severed breasts on a banana leaf.

Does anyone know of a book that similarly recounts the history of China's South, where my ancestors are from? If not, someone should write it!

The Body Keeps the Score, by Bessel van der Kolk

Penguin, 2014

Wowee, this 400-page book is heavy-going. You'd figure the central theme of the work is easy enough to communicate—that psychic trauma has physiological effects—but this Dutch-American psychiatrist has been working on this since 1978, and he's got sh*tloads of stories and ideas to spill.

One of the biggest pills to swallow is the extent of what trauma is like. He's treated veterans from World War Two and Vietnam stuck in the horrors they've experienced and committed on the battlefield; civilians exhibiting the same PTSD symptoms because of family violence, rape, incest, even witnessing violence—not just having panic attacks and drug and drinking binges but also becoming dangerously violent towards their own loved ones. Specific correlations have been found btw trauma and long-term physical health in terms of blood pressure, immunity, brain development, overeating... e.g. there are cases of people compulsively making themselves obese so that no-one will ever sexualise them again. (Many self-destructive behaviours actually have self-protective motivations; when patients act up they're often preserving themselves the best way their bodies know how.)

Van der Kolk speaks of a pandemic of trauma going on, repeating through generational cycles (he started to understand some of his own World War Two veteran dad's outbursts of rage), concentrated in economically disenfranchised communities, and he complains of how governments and DSM just don't take the situation seriously, repeatedly defunding their research and denying the inclusion of "developmental trauma disorder" in their manual. Also of efforts to discredit the testimonies of child rape survivors—he's treated those abused by Catholic priests; how they need therapy to even recall what causes their current self-destructive behaviour; how they exhibit consistent patterns of amnesia and eventual accurate recall. (Trauma tends to leave you with flashes of details w/o connecting narrative; those who can exhibit agency during a violent event are far more likely to make sense of it and escape without scars.)

So what's to be done? Neither a purely medication-based treatment (the current norm, thanks to big pharma) nor the Freudian talking cure works alone. What really helps involves addressing the body directly—not just through familiar therapies like yoga, martial arts and theatre and song, that help folks regain a sense of control over their bodies. But he also advocates less familiar treatments: neurofeedback, EMDR (eye movement desensitisation and reprocessing, almost like hypnosis as you stare at moving fingers), IFS (internal family systems therapy, involving role play). All of which he was initially skeptical of but was wowed by when he saw the results. And apparently there's success with treating ADD with neurofeedback too!

Also, I'm now even more furious at warmongers like Putin and Bush, whose actions cause generational waves of trauma. and kinda shocked at the realisation that PTSD was only coined after analysing the effects of American Vietnam War vets (studies of World War One vets were actually downplayed cos they were harming recruitment efforts). And that what traumatised several of these guys was the act of slaughtering and raping Vietnamese people. Dudes, I know you're sick, but how am I supposed to feel sorry for you?

Ng Yi-Sheng (he/him) is a Singaporean writer, researcher and LGBT+ activist. His books include the short-story collection Lion City and the poetry collection last boy (both winners of the Singapore Literature Prize), the non-fiction work SQ21: Singapore Queers in the 21st Century, the spoken word collection Loud Poems for a Very Obliging Audience, and the performance lecture compilation Black Waters, Pink Sands. He recently edited A Mosque in the Jungle: Classic Ghost Stories by Othman Wok and EXHALE: an Anthology of Queer Singapore Voices. Check out his website at ngyisheng.com.

If you’ve enjoyed reading this article, please consider making a donation. Your donation goes towards paying our contributors and a modest stipend to our editors. Singapore Unbound is powered by volunteers, and we depend on individual supporters. To maintain our independence, we do not seek or accept direct funding from any government.

This Christmas season, Ng Yi-Sheng takes us to the Middle East.