#YISHREADS February 2025

By Ng Yi-Sheng / @yishkabob

A bit of real talk. I’ve always enjoyed the ritual of doing a Black History Month column, but I’ve also found it a little absurd. Here in Singapore, it’s hardly an act of social justice—we don’t have a Black underclass, after all—so it all ends up being a display of cosmopolitanism; an artificial American import, rather like a St. Patrick’s Day Parade or Friendsgiving.

However, the act feels a little more political this year. President Trump’s made an executive order to terminate DEI programs, and though he hasn’t actually gotten rid of Black History Month, [1] various bodies have eagerly leapt to comply ahead of orders, including the Department of Defense and Google Calendar. Add to that his dismantling of USAID, which endangers activists worldwide, and which has already caused deaths with the termination of food and healthcare programmes in sub-Saharan Africa.

It feels a little ridiculous to try, as a cultural worker, to push back against this evil with symbolic acts—everyone loved Kendrick Lamar’s Super Bowl halftime show, with Samuel L. Jackson as Uncle Sam and Serena Williams crip walking, but how many lives did it save? Then I remember the fact that one of the dancers, Zül-Qarnain Nantambu, seized the chance to unfurl the flags of Palestine and the Sudan, using his hour in the spotlight to cry out, to demand change.

These gestures must be worth something, then, or else why would people try to suppress them? So here are five works from the African diaspora, from American dystopian literature to Ethiopian medieval religious scripture to Nigerian-British chick lit set in Singapore. Vastly divergent—that’s what the D in DEI stands for, almost!—but with a whole bunch of resonances between them, with shared themes of gender, crisis, journeys, hope and home.

Parable of the Sower, by Octavia E. Butler

Headline, 2019

Confession: this is my first time reading anything by this legendary sci-fi author—at least, anything longer than a short story. Wish I’d started sooner, though, cos this novel is frickin’ devastating.

Folks were buzzing about this in January, because of how prophetic it had become. Though first published in 1993, its early chapters take place in a 2025 when the USA is reduced to an anarchic wasteland, ruled by the hyper-right-wing President Donner, with slavery making a return and all of California going up in flames.

Naturally, it doesn’t get our era 100% right—on one hand, there are colonies on the Moon and Mars; on the other hand, the breakdown in social order is so severe that almost all urban areas have collapsed. It is one where the majority of Americans are illiterate, where trains of refugees are tramping across the Western seaboard in search of safety and work, abused by pyromaniac drug addicts and literal cannibals. But it's harrowingly imaginable right now, with the US gleefully dethroning itself from first world status, with no easy promise of restoration through the next voting cycle.

The story's told from the POV of Lauren Olamina, a teenager born with a bizarre disability called hyperempathy which causes her to experience any pain she witnesses in others—which is pretty gnarly, since she's witnessing the decay of her village, where her preacher dad's a leader of the community, and eventually has to flee on foot with surviving neighbours, walking the highways, defending themselves with knives and firearms. She endures terrible loss and sees the worst of horrors, yet she's smart and strong, even conceiving a new religion called Earthseed, premised on the idea that God is Change and that our destiny is to spread humanity across the stars.

So this is a jaw-droppingly bleak dystopia, yet it's also arguably hopepunk. Despite everything, Lauren builds community and trust, never out of sentimentality or naïvété, but out of knowledge that it's the only thing you can do if you want some kind of civilisation to survive.

I speak in terms of contemporary SFF categories, but what's also refreshing is that this predates 21st century tropes—there's a ton of ethnic diversity but no heavy-handed efforts at cultural representation; there's romance and sex but it's accepted that you must survive the loss of your lover; there's sexual violence but it doesn't necessarily define its survivors. Or perhaps what makes this distinct is its emphasis on the collective rather than the individual—don't think we see those values as much today.

One last hook for the reluctant reader. Today, this is heralded as a literary classic, but it reads quick, cos it's still fundamentally written for young people. I can only hope to boast of one day writing something like that!

The Kebra Nagast: The Queen of Sheba and Her Only Son Menyelek

Translated by E. A. Wallis Budge

ZuuBooks 2011

This 14th century text is regarded as the national epic of Ethiopia, a sacred text to both Ethiopian Orthodox Christianity and Rastafarianism! Unfortunately, this specific version that I bought off Amazon a few years ago is one of the older, crustier translations thereof, dating from 1932 by the Keeper of the Department of Egyptian and Assyrian Antiquities in the British Museum.

The text itself is rather cool because of its Afrocentric retelling of Biblical events. The central chapters focus on the relations between Makeda, the Queen of Sheba, and King Solomon: how she hears of his glory from the merchant Tamrin; how she goes on multiple visits to Jerusalem to learn from his wisdom; how he tricks her into giving up her virginity by feeding her peppery fish and vinegary drinks until she needs to grab a drink of water from his beside, whereupon he goes, “Ha ha, you broke your oath not to steal from me!”; how she returns to Ethiopia and births Bayna-Lekhem (i.e. Menyelik), who eventually grows up the spitting image of his dad, goes to Jerusalem where he’s welcomed (Solomon hasn’t had a lot of other kids), and steals the Tabernacle of the Law of God, replacing it with a dummy replica and bringing the real one back home, all of which was foreseen by Solomon in a dream the very night his son was conceived: the sun departing Israel to rise over Ethiopia.

There’s also a little extra tale of how Makshara, daughter of the Pharaoh, corrupts Solomon by tricking him into bowing before the gods of Egypt—and it does really feel like there’s a fair bit of attention given to remarkable women in this holy book, with invocations of Mary and Eve. Even the Tabernacle’s feminised as the Lady Zion! Alas, it’s hardly what we’d call feminist: Makeda actually declares she’ll change tradition so that the rulers of her kingdom will go from being exclusively female to exclusively male. Not to mention that a lot of the leftover stuff is rather boring snippets about Abraham, Ezekiel and Moses, plus the Church of Rome vs. Ethiopia.

I’d say it isn’t essential to read this whole thing unless you’re deeply curious about African culture—and definitely get a more up-to-date edition, maybe one that talks about the work’s influence on Rastafarian belief. This one’s intro just compares it to “Muhammadan” legends of the Queen of Sheba, which are, admittedly, not uninteresting (there’s a whole thing about her being born with a single hairy donkey’s leg, which clears up when she hitches up her skirts to pass through Solomon’s glass courtyard), though ultimately repetitive. Completionism’s only a thing if you’re a nerd like me.

The Palm-Wine Drinkard, by Amos Tutuola

Faber and Faber, 2014

This 1952 Nigerian novella’s a classic: the first African novel in English to be published outside the continent, praised by T. S. Eliot and Dylan Thomas, ranked as one of the top 100 fantasy books by Time! [3] Still, I've gotta be honest—it's also a bit of a challenge to follow, even compared to the author's 1954 novel, My Life in the Bush of Ghosts; even if you don't count the eccentric orthography (e.g. the use of “drinkard” rather than “drunkard” in the title), the random interjections of brackets and capitalised lines.

Our protagonist, a guy with a prodigious capacity for drinking palm wine (later self-called "Father of gods who could do anything in this world"), discovers that the guy who taps his wine is dead, so he naturally goes on a quest to retrieve him, on the way capturing Death himself, rescuing a young woman from a handsome lothario called the Complete Gentleman who's just a magic skull who rents all his other body parts, transforming himself into a canoe so his wife can earn money as a ferrywoman, turning into a bird so he can fly across the bush, dallying in a termites' house and on Wraith-Island and Unreturnable-Heaven's Town and with the Faithful-Mother in the White Tree and the Red-People in the Red-Town and Invisible-Pawn and the Wise King...

Before finally arriving at Deads' Town, where the tapster says he can't go with him, sorry, but here's a miraculous egg which he then uses to generate infinite food for his village during a famine, till it breaks and he gets pissed with all the parasites and uses it to generate infinite whips to flog them with. (I left out the ordeal with the four hundred dead babies and in the Hungry-Creature's stomach, but you get the picture.)

Basically, this is a story written with very little regard for modern/Western ideas of plot and character development, borrowing liberally from Yoruba folktales, and the end result is a work so psychedelic and chaotic that it makes Ngũgĩ's Devil on the Cross look like Jane Austen’s Pride and Prejudice. I can't help but be in awe of it, but also sympathetic to all the African theorists who couldn't accept it as canonical (was it only beloved by white modernists as exotica?). And I'm curious about the 1968 opera version, but also thoroughly aware that any adaptation thereof is bound to make the work more coherent and digestible, when part of its uniqueness is its refusal to meet the standards of others.

I'm choosing to regard it as an icon of literary liberation—this is what a fantasy novel can be, regardless of what readers expect and demand. I am my own most important audience. Tolkien can go kick rocks.

In Such Tremendous Heat, by Kehinde Fadipe

Renegade Books, 2023

As advertised earlier, this is chick lit about a trio of glamorous Nigerian women in Singapore, actually marketed in the US under the title The Sun Sets in Singapore. Pretty nifty, no? But I’ll be honest: I’ve got pretty mixed feelings about this.

On one hand, the perspective's pretty unique. We follow three principal characters: Dara, a Yoruba-British high-flying corporate lawyer working on a big case between Japanese investors and Kenyan tribal chiefs; Lillian, a Tiv-American pianist-turned-expat wife ESL teacher going slowly crazy cos her husband wants a baby; and Amaka, a shopaholic Igbo banker dating her Indian-Thai colleague who's caring and wealthy but whom she's convinced doesn't see her as marriage material. We see the island through their eyes, from the colonial grandeur of Singapore Cricket Club and Raffles Hotel (white people committing microaggressions everywhere), to the sultry sands of Tanjong Beach Club, the humbler HDB corridors of Yishun (where they get used to being stared at), and the ambivalent condition of being pretty safe from violence, sexual harassment and racial profiling, but also not quite being accepted, never being home.

On the other hand... well, the prose is stilted and unstylised, prone to dry over-explanations, adverbs and tom swifties, and the perspective's kinda neocolonial: actual Singaporean characters are incredibly marginal (a helpful coworker, an unreasonable cab driver, maybe the boss Indira?)—Singapore's merely a hyper-capitalist arena the three ladies have to navigate, our culture so indistinct that I wouldn't even say the setting is a character in the story, as so many works of fiction may claim. Understandable that Fadipe wrote us this way—it's hard for foreigners to assimilate into the Singapore we citizens experience. But it's not the kind of book I'd tell people to read if they want a taste of our country.

Nevertheless, moving forward through the book, its charms come more to the surface: I found myself sucked into the chaos when Lani, a stunningly handsome but amoral Nigerian lawyer, enters the scene, with characters’ hidden traumas revealed, flashbacks to childhoods in Lagos, grapplings with African masculinity and solidarity, and importantly, I think, inexcusable acts having consequences.

And I wonder, reading the back blurbs, if the Singapore setting means a lot more to Black readers than what I'm getting—a promise that there are places, beyond the Euro-American world and Africa, where Black people can prosper, if not actually call home. Weird, huh? After Crazy Rich Asians, folks were saying Singapore was Wakanda for Asian-Americans. With her portrayal of Black elite community, is Fadipe suggesting we could also be Wakanda for Black folks?

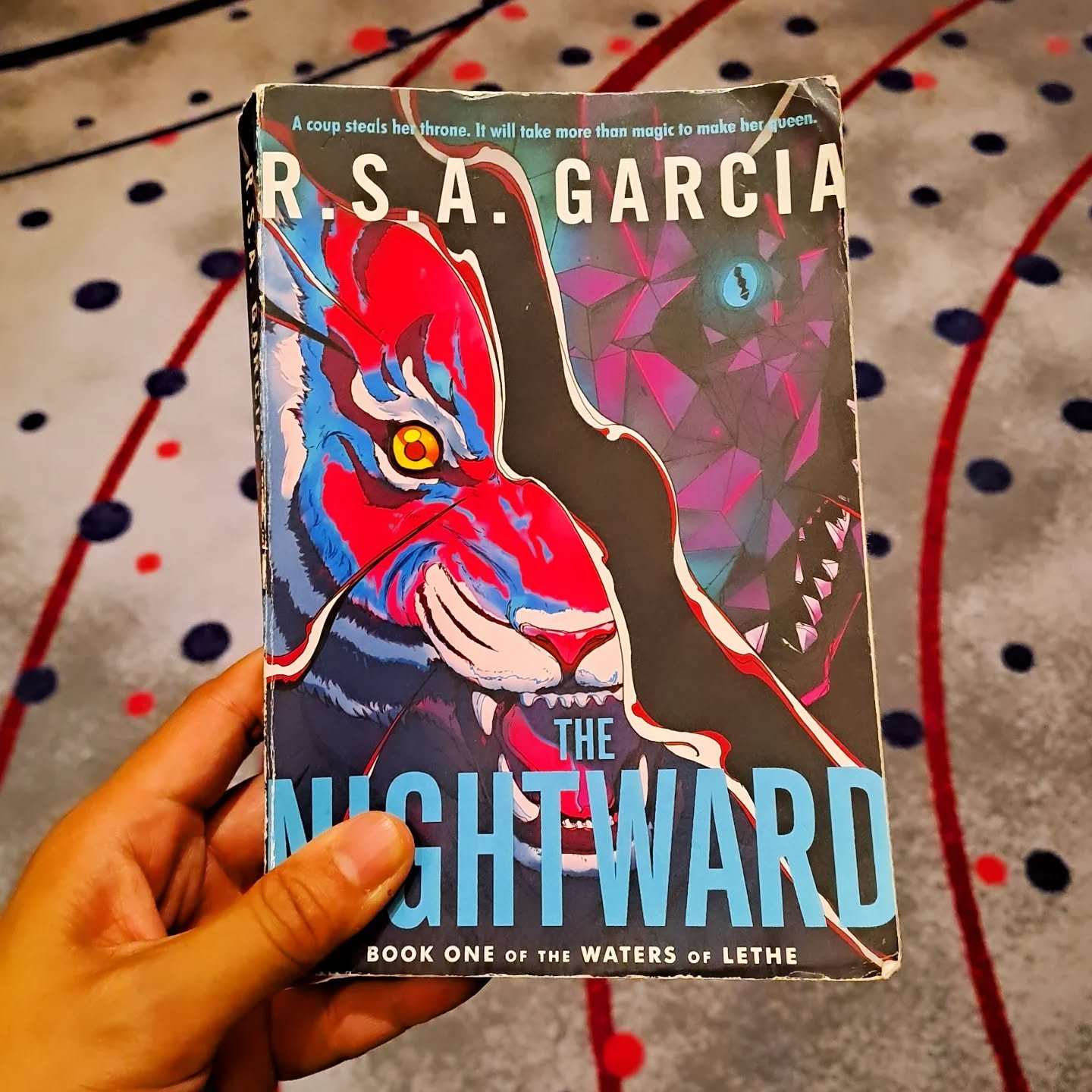

The Nightward, by R. S. A. Garcia

Harper Voyager, 2024

I actually wrote about this author's journey in my essay "A Not-So-Swiftly Tilting Planet: Global Inequities in SFF Publishing!" [4] This is her first traditionally published novel after twenty-two years of short stories and self-publishing while based in Trinidad and Tobago—an inspiration to all of us who haven't yet quite made it in the global world of spec fic.

The novel itself, however, isn't what I'd expected. Garcia’s known as an author who celebrates Caribbean culture and science fiction—check out her Nebula-winning short story, "Tantie Merle and the Farmhand 4200." [5] But this book's a swords-and-sorcery work of fantasy (slight spoiler: there are sci-fi elements peeking through the cracks), set in a fundamentally Eurocentric world of knights and nobles (sure, there are dark-skinned characters and folks wearing saris, but most of our central characters have light skin and hair, and the sacred language turns out to be modern French!).

Which is to say, Garcia isn't doing identity politics here. Instead, just like Butler, she's being prophetic. The inciting incident is a bloody coup in the Court of Hamber, threatening to overturn the matriarchal queendoms of Gailand in favour of the male sorcerer Mordach, his puppet prince Valan and his allies, the male-dominated Ragat tribe. And this narrative of the utter decimation of an established order in favour of ruthless, destructive, male-centric policies feels incredibly descriptive of the current Trump/Vance administration's gutting of the US government.

We follow those fleeing from and reacting to this cataclysm: the 19-year-old bodyguard Luka Freehold, sworn to protect the 10-year-old Princess Viella (now Queen) and accompanied by the stubborn knight Eleanor; the seer Neisha and the Lady Gretchen, using what magic they can to resist Mordach's machinations; an unnamed fishtailed River Maiden, questing through chthonic gates and challenges to plead for help from the First Mother. And again, it feels like a record of how ordinary people have to struggle to survive and find a way out of these desperate times.

The work’s not perfect by any means—I’m not too happy with the depiction of the Ragat people, who're currently represented kind of as a one-dimensional evil race, like orcs or Calormens. And though I know this is just volume one of a duology, the ending still strikes me as too damn abrupt, a devastating abandonment rather than the closing of an act.

But maybe all will be forgiven after volume two, no? And these are the times we live in. Good doesn’t triumph over evil that quickly. And sequels are always waiting beyond our line of vision, promising both hope and havoc.

Endnotes

[1] “National Black History Month, 2025.” The White House. 31 January 2025. https://www.whitehouse.gov/briefings-statements/2025/01/national-black-history-month-2025/

[2] Kizito Makoye. “Death, disease and instability: Africa faces crisis on all fronts after US aid cut.” AA. 12 February 2025. https://www.aa.com.tr/en/africa/death-disease-and-instability-africa-faces-crisis-on-all-fronts-after-us-aid-cut/3479592

[3] “The 100 Best Fantasy Books of All Time.” Time. 15 October 2020. https://time.com/collection/100-best-fantasy-books/

[4] Ng Yi-Sheng. “A Not-So-Swiftly Tilting Planet.” Strange Horizons. 28 August 2023. http://strangehorizons.com/non-fiction/a-not-so-swiftly-tilting-planet-global-inequities-in-sff-publishing/

[5] R. S. A. Garcia. “Tantie Merle and the Farmhand 4200.” Uncanny. July/August 2023. https://www.uncannymagazine.com/article/tantie-merle-and-the-farmhand-4200/

Ng Yi-Sheng (he/him) is a Singaporean writer, researcher and LGBT+ activist. His books include the short-story collection Lion City and the poetry collection last boy (both winners of the Singapore Literature Prize), the non-fiction work SQ21: Singapore Queers in the 21st Century, the spoken word collection Loud Poems for a Very Obliging Audience, and the performance lecture compilation Black Waters, Pink Sands. He recently edited A Mosque in the Jungle: Classic Ghost Stories by Othman Wok and EXHALE: an Anthology of Queer Singapore Voices. Check out his website at ngyisheng.com.

In Taiwan Travelogue, ‘twinned souls… are at once lost, but also found, in translation.’ A review by Eunice Lim.