#YISHREADS November 2023

By Ng Yi-Sheng / @yishkabob

Deepavali / Diwali, the Festival of Lights, just happened this month, so I figured it’d be a great time to look at speculative fiction from South Asia and the diaspora!

At first, I’d hoped to make this a follow-up to #YISHREADS August 2022,[i] which looked at retellings of Chinese history—maybe a survey of works reimagining the epics of the Ramayana and the Mahabharata, like Chitra Banerjee Divakaruni’s The Forest of Enchantments and Krishna Udayasankar’s The Aryavarta Chronicles. But I also wanted geographical diversity, hence the inclusion of Sri Lankan and Bangladeshi authors already on my TBR list. (Sorry, Pakistan, Nepal and Bhutan! Another time, I promise.)

Thus, as you can see, my selection’s a very mixed bag, spanning the worlds of pulp horror, cyberpunk and mythic realism (which is how Indrapamit Das describes their novella); running the gamut from the transcendent to the jaw-droppingly bad! But all fascinating, with the authors dealing with their individual cultural heritages in diverse and unexpected ways.

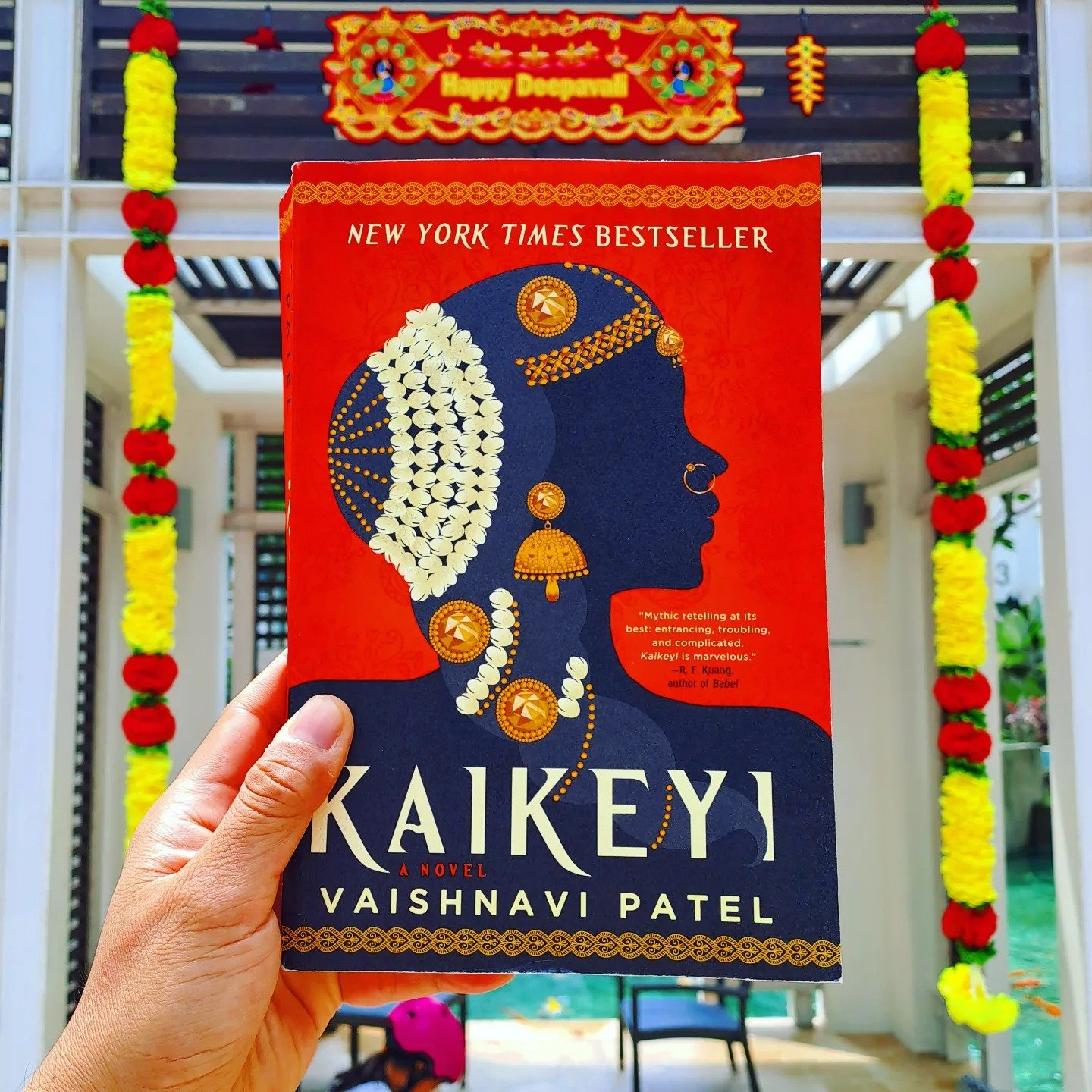

Kaikeyi, by Vaishnavi Patel

Redhook Books, 2022

Yup, it's an Indian-American retelling of the Ramayana from a feminist perspective, specifically from the POV of one of the most reviled characters in the epic: Kaikeyi, the evil queen who exiles Rama from the court of Ayodhya so her own son may take the throne.

Started this out with some skepticism: the premise seems a little obvious in the age of Madeleine Miller's Circe and Disney's Maleficent, and the opening chapters focus on her as a young disempowered princess learning the arts of war—a classically ya-ssified way to demonstrate that our heroine's not like other girls. But the story builds and grows more complex as she grows older and events foreshadow her impending downfall, all her accomplishments destined to be lost as she hurtles towards her destiny as the ultimate villainess.

And here's what really drew me in: realising that this is a novel for the age of Hindutva. Rama isn't introduced as the classic hero of old; he's a child with godly powers of influence and charisma, but he's also got a horrifyingly patriarchal ideology that he uses to try to reverse Kaikeyi's feminist reforms—as a 10-year-old kid, he calls her a whore for going in public to hold council. And while it's revealed that this is due to the regressive influence of conservative sages—he keeps lapsing between bully and youth, genuinely showing respect and affection for Kaikeyi as one of his mothers—there's also a sense that the gods are either responsible for this misogynistic ideology or else quite content to let it thrive.

And yes, the gods exist in this story. I’ve heard from Udayasankar how dangerous it is to portray any divine characters as a Hindu author, but while Patel's got the privilege of living in the USA, she's doing this very cleverly, first having Kaikeyi mourn the fact that the gods never answer her prayers (hinting at a realist setting), learn a form of magic that allows her to manipulate influence, and fight off rakshasas (OK, so this is fantasy), then be confronted with gods like Agni and Saraswati who tell her directly that she's gods-touched, born to fulfil her role in history, which is why they won't answer her prayers. The gods are present, but they're not necessarily working for the good of humanity—or if they are, they don't consider women as fully human.

Lots of other thoughts—an inventive treatment of Ravana and Sita; the strange decision not to have Manthara (Kaikeyi's handmaiden) be hunchbacked as she's usually portrayed; likewise having Kaikeyi be asexual in orientation; a focus on an intersectional feminism with the queens reaching out to maidservants and working-class wives; the somewhat unsatisfying realisation that our main character's going to be shown as having pure intentions throughout rather than being at least a bit selfish; the somewhat open-ended conclusion which doesn't even feature Rama's battle with Ravana, let alone his shoddy treatment of Sita in the wake of his victory.

But on the whole, a helluva coup, and it's great that we don't have to keep recommending Sita Sings the Blues as the major feminist reworking of the epic, now that Nina Paley's come out as a TERF.

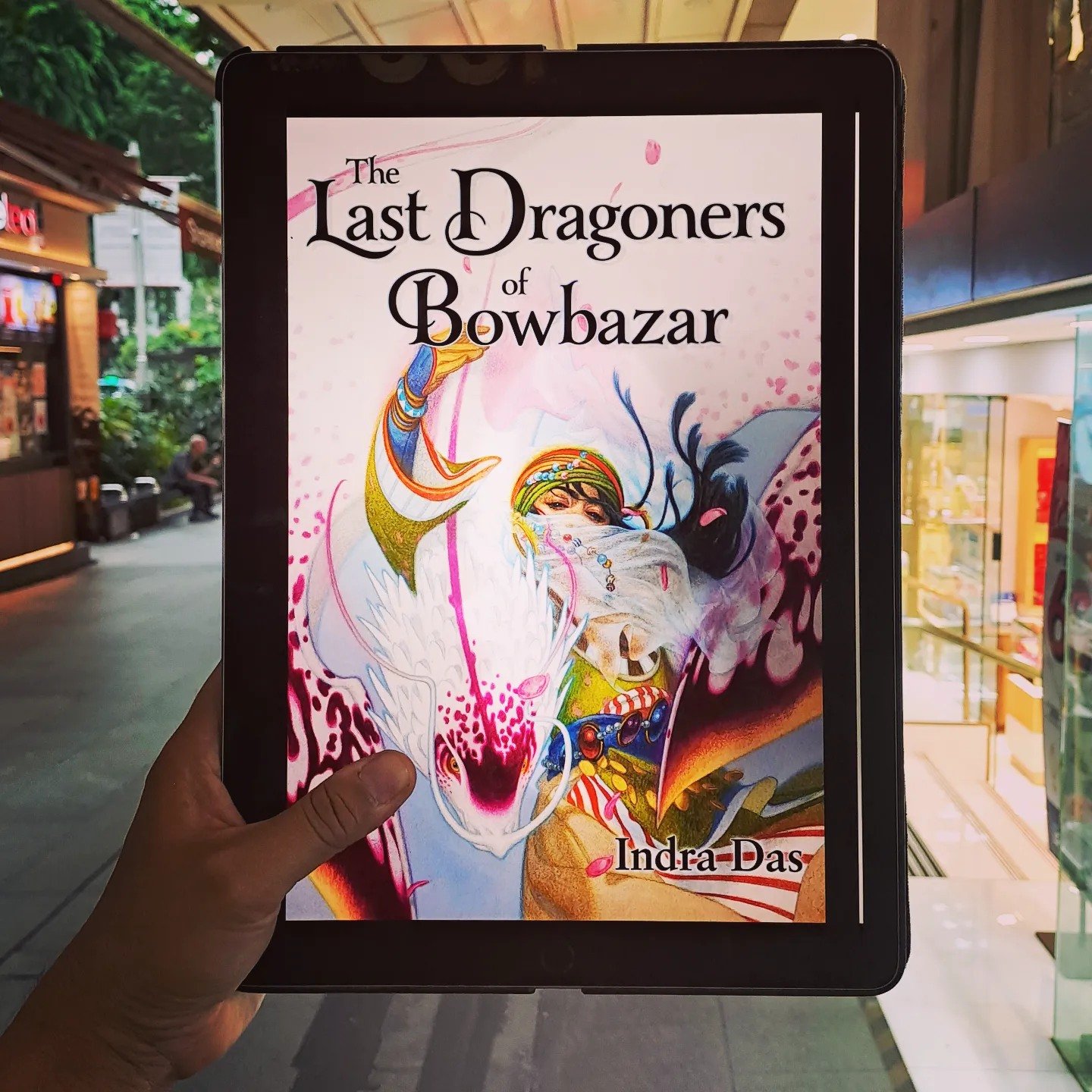

The Last Dragoners of Bowbazar, by Indrapamit Das

Subterranean Press, 2023

I'd thought this novella would be one of those classic second-world fantasies with a bit of South Asian exotica thrown in—but I should've known the author (whom I made friends with at the Singapore Writers Festival) would do something way more kick-ass.

Surprisingly, pretty much the entire story takes place in Kolkata in the 90s and 2000s, following Ru as he/they grows up (they're implied to be nonbinary), goes to school and has an awkward friendship/romance with the Chinese girl Alice who lives next door. It's a whole X-ennial narrative, with them watching Lord of the Rings, listening to Slipknot and getting email accounts at Internet cafes as rites of passage.

The fantasy element is that Ru comes from a clan of divine beings who ride, worship, eat the flesh of and descend from dragons—yet he's never allowed to absorb all of this culture, forced to drink the Tea of Forgetfulness after every encounter, so that they're deprived of their own culture and heritage, knowing only that he's an outsider from the mainstream Hindu Bengali world of his schoolmates. So the whole thing's weighted with the loneliness of being a modern descendant of diaspora, alienated from both your roots and your national/regional identity.

Then there's the meta element: Ru's dad is an avid reader of SFF, with his shelves lined with Asimov and Tolkien, but also a failed fantasy writer, having published a single novel (about dragons, of course) with a US press, which sold only 52 copies before getting pulped. He's inscribed the true history of the dragoners, this interdimensional race who came to Earth, into mass-market fiction, only to be told the Western world doesn't want it. Pretty f*cking familiar, especially since the story he's trying to sell isn't a classically "Indian" tale—he's from the margins of the margins, so no-one's gonna get how important his story is.

But to reiterate: maybe what I love the most is the fact that this is so damn rooted in the city of Kolkata: Chandni Chowk metro, New Empire cinema, Central Avenue and the British Council Library—to the extent that you occasionally wonder if the dragons are just a metaphor, just a made-up way of grasping the world like in The Bridge to Terabithia. But not to worry: by the bittersweet end (minor spoiler I guess?) there's just a peek beneath the veil; a way for all of us lost X-ennials to believe we can be the bearers of our culture into the future. That, despite everything, magic is also our inheritance.

Cyber Mage, by Saad Z. Hossain

Unnamed Press, 2021

And here’s a work that happily marries myth and cyberpunk! Set in a dystopian nanotech-governed hypercapitalist future Dhaka, this is a tale of the 15-year-old genius hacker, Marzuk, caught in a war between sentient AIs and murderous djinn, all while going to high school and avoiding bullies and trying to get a cute girl to like him.

TBH, it's a little more YA-centred than what I'd like—all action, no poetry, more investment in tech-driven worldbuilding than representations of Bangladeshi culture (beyond the biryani, samosas, beer and shocking gaps btw the microclimate-enjoying rich and the slum-dwelling radiation-exposed poor) or historical explorations of what it means to have had djinn living among us for millennia, impersonating Egyptian gods. Really heterosexual—even AIs start having sexual chemistry based on their gendered representations.

Still, it does capture the quandary of teen nerditude very well (this Final Fantasy warlord suddenly realises how he's a noob at real life), the struggles with the body (Marzuk is chubby, and another character, Leto, has spinal deformities which he compensates for with a combat exoskeleton). and the predictions of how in the future, nation-states might collapse in favour of corporations, with Singapore the first country to abandon the social contract of citizenship in favour of turning its people into shareholders (and ejecting the undeserving?). That's bleak, man, and right on the money.

Numbercaste, by Yudhanjaya Wijeratne

Self-published, 2018

This here's a near-future novel, set mostly in the 2030s and 40s, about a tech company, Number, that calculates people's social credit and gradually expands to become a totalitarian tool controlling all of human life.

It's told from the POV of Patrick Udo, a company copywriter who ends up becoming a master of marketing and spin—his biggest coup is creating a webseries, also titled Numbercaste, that both promotes the company and prophesises its popular impact—and who provides an inside view of how long you can keep running along with an institution as it gradually reveals its internal corruption.

It's not bad. Not exactly sensational: the prose isn't lyrical, the ending feels very wonky, and the imaginative possibilities of the tech are human-scaled rather than space operatic. Still, it's breezy, with decent drama and action, and the story's pretty damn convincing, especially when you recall how Google's shareholders voted away its “Don't be evil” rule, and when you consider the author's background as a big data researcher and journalist—lots of chillingly familiar abuses of press freedom here: not just buying up editors and politicians, but a future where the Internet isn't forever: where you can scrub human knowledge clean of any data you want obliterated.

What's pretty damn interesting too is the way Wijeratne weaves his own Sri Lanknanness into the story. At first it seems absent: Udo is a Black Chicagoan who goes to work for Number's founder, Julius Common, in San Francisco—there's a number of Desi names among the staff, but that's nothing unusual in the USA tech world.

Then Number does its first Asia launch in Sri Lanka, where Julius has his holiday home; Udo devotes several chapters to the struggle of the company to succeed in India, culminating in his travelling the country to create his award-winning webseries; we learn that Julius has been collaborating with a Chinese partner, Liu Heng, all along, and that the whole system is based on China's real-life experiments into assigning social credit. (A bit of Orientalism in claiming that it's based on Confucian ideals of guanxi, IMHO.)

And then finally, in an appendix detailing Common's beginnings, we discover that he's actually got an estranged Sri Lankan dad whose genius was hobbled by racism and his own self-destructive habits. So this whole narrative really has been about a brown man (with white and East Asian connections) taking over the world. A power fantasy of sorts—despite the ruthless elitism of Number, Julius reiterates that it doesn't discriminate based on race or religion, and even penalises overt racists—but also a profession that South Asians would be just as amoral neocolonialists as white folks if given the chance.

Rakasa, by Pugalenthi Sr

VJ Times, 1995

Of course I had to include a Singaporean Indian SFF author in this series! But tracking one down is a little harder than you’d expect: Anittha Thanabalan’s only written one novel, The Lights That Find Us, which I read ages ago; Vina Jie-Min Prasad only has uncollected short stories; Manish Melwani only has short stories and a novelette.

So I’ve decided to go way back to the infamous horror boom of the 1990s, to the oeuvre of pulp publisher Pugalenthi Sr, who edited not only ghost stories but also collections of myths and legends, joke books and even occasionally literary works, ultimately venturing into writing himself.

Rakasa is one of his early novels, taking the form of the diary of an unnamed protagonist—an obnoxious, pointlessly antagonistic incel—who discovers his latent powers of black magic as a reincarnation of a powerful Johor bomoh. And I’ve gotta be honest: this isn’t a forgotten gem. It’s bad in multiple ways, from the amateurish and unfocussed writing to the eye-popping misogyny and violence against women, not to mention the simple fact that the story doesn’t actually have a conclusion—the protagonist (who eventually names himself Rakasa) just grows in power and inner turmoil, then that’s it, finito, no 31 December showdown, not even the promise of a sequel to explain what happens next.

Basically, this feels like a first-time novel challenge, with Pugalenthi literally writing one entry per day and sharing the results almost verbatim—there’s even an incomplete version titled Rakasa: The Awakening, published in 1994 with horror art!

But there are some pretty cool things about this novel. First, the format—dated entries for 1993, allowing Rakasa to sneer at the customs of Chinese New Year and National Day; even foreseeing the bloody end to the Waco Siege before it happens. There’s a grotesque parody of yuppie culture of the 90s, with Rakasa working as an insurance salesman (everyone he sells to gets a huge payout, cos they die mysteriously), buying and winning lottery sweepstakes, moving out of his rental flat into a bungalow, resenting and destroying anyone he sees as more successful than himself.

And perhaps most intriguingly, the way the story locates itself at an intersection of cultures. Rakasa’s own race isn’t revealed—he specifically notes that he’s been mistaken for an Indian—but he has friends, colleagues and rivals of all races, and devotes pages and pages to ramblings about Dalí, Nietzsche, Lovecraft, the Chinese occult, Hindu theology, kabbalah. Ultimately, however, the core of his magic is Malay: he has to return to the Johor jungles regularly to engage in rituals, to draw from the powers of toyol and jinn he’s buried in the ground, to have sex with his undead lover Katina.

Arguably, it’s all reflective of a Singaporean quest for meaning: thoroughly cosmopolitan, but still dependent on rootedness in Malay lands beyond our borders. But it’s also reflective of how Indian Singaporean writers have shown a reluctance in drawing on their heritage in the crafting of spec fic stories—the protagonist in this case likes the name “Rakasa” not because of its similarity to “rakshasa”, but because it sounds like a fashionable Western name, for chrissakes. Not informed enough to theorise why it’s been like this thus far—but I think it’ll change. There’s just so much folks of South Asian descent can bring to our ongoing wave of spec fic.

Endnotes

[i] Ng Yi-Sheng, “#YISHREADS August 2022”. Suspect, 26 August 2022. https://singaporeunbound.org/suspect-journal/2022/8/26/yishreads-august-2022

Ng Yi-Sheng (he/him) is a Singaporean writer, researcher and LGBT+ activist. His books include the short-story collection Lion City and the poetry collection last boy (both winners of the Singapore Literature Prize), the non-fiction work SQ21: Singapore Queers in the 21st Century, the spoken word collection Loud Poems for a Very Obliging Audience, and the performance lecture compilation Black Waters, Pink Sands. He recently edited A Mosque in the Jungle: Classic Ghost Stories by Othman Wok and EXHALE: an Anthology of Queer Singapore Voices. Check out his website at ngyisheng.com.

If you’ve enjoyed reading this article, please consider making a donation. Your donation goes towards paying our contributors and a modest stipend to our editors. Singapore Unbound is powered by volunteers, and we depend on individual supporters. To maintain our independence, we do not seek or accept direct funding from any government.

#YISHREADS returns with the theme of sequels, you know, that genre that everyone loves to hate.