The View of Mukja: The Invisible Voices of Hwang Jungeun’s dd’s Umbrella

by Taeyeon Song

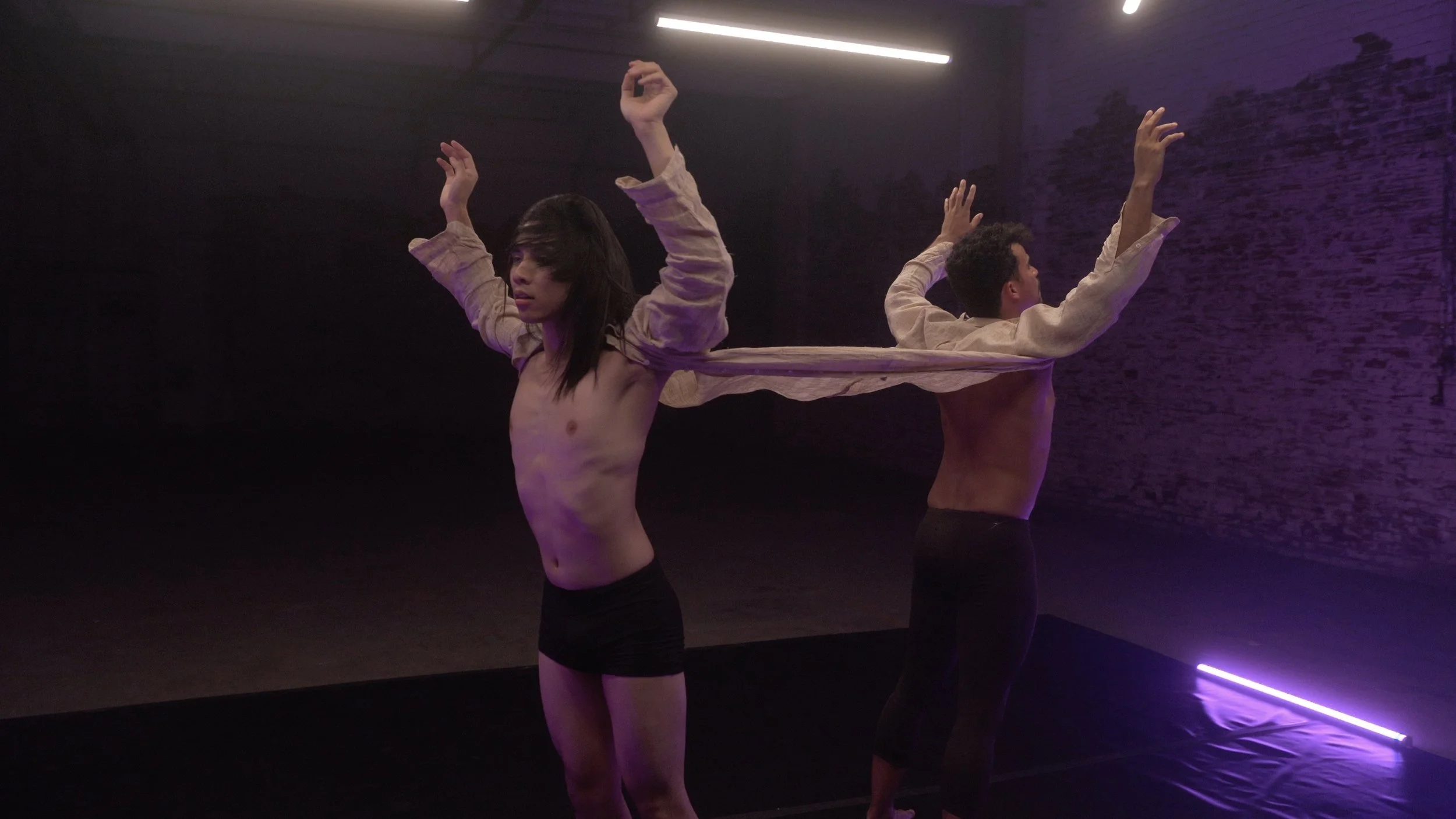

Kang Seung Lee - Lazarus (2023), Single-channel 4K video, color, sound, 7 min 52 sec

Courtesy of the artist, Commonwealth and Council, Los Angeles; Gallery Hyundai, Seoul; Alexander Gray Associates, New York.

Image description: Two individuals stand a short distance apart in a dark-walled room lit with purple-tinted light. They have their backs to each other and hold up their arms. They are held together by a stretch of white fabric between them, which are attached to their sleeves, as if their shirts are connected together at the ends. They are unclothed except for black shorts.

Author’s note: I must preface this review of dd’s Umbrella by stating that I am a cisgender, heterosexual Korean woman who does not have a disability. In my reading of dd’s Umbrella, I do not wish to appropriate the lived experiences of or speak over the voices of Korea’s LGBTQ+ or disability communities, who are already deeply marginalised and underrepresented. Instead, I analyse dd’s Umbrella through the lens of a Seoulite who read this novel in the days following the martial law declaration by President Yoon Seokyeol in the late evening hours of December 3, 2024.

In dd’s Umbrella, narrator Kim Soyoung says:

‘We don’t need to know.’

I have a name for this type of attitude. I call it the view of mukja.

Kim Soyoung then explains that after being told by a doctor she is gradually losing her sight, she learns that ‘mukja’ is the term for written reading and writing systems – something so normative for sighted people that many live their entire lives without learning the proper terminology for it. Later, standing on a train platform and observing the written notices for arriving trains, Kim Soyoung realizes, “One day, I, too, would be erased. From the platform of mukja, from the supposedly uniform and unvarying common-sense world, yet again.” Thus, the view of mukja is one in which a lack of knowledge stems not from wilful ignorance, but rather from the lack of a necessity of knowing – rendering those outside of the view of mukja invisible and silenced. The view of mukja is the lens through which author Hwang Jungeun articulates the experiences of those who are placed at the margins of left-wing political movements. In dd’s Umbrella, it refers specifically to the protests in the aftermath of the MV Sewol disaster and the lead-up to the subsequent impeachment of former President Park Geunhye.

dd’s Umbrella is written by Hwang Jungeun and translated from the original Korean (디디의 우산, 2019) by e. yaewon. dd’s Umbrella is a poignant and meaningful addition to Hwang’s already extensive list of published work, which includes One Hundred Shadows [백(百)의 그림자, 2010], Passi Enters the World [파씨의 입문, 2012], and No One [아무도 아닌, 2016].

dd’s Umbrella is a work of historical fiction comprised of twin novellas. The protagonists of each novella identify as members of the queer community, informing the manner in which they experience the national tragedy and following political upheaval. The work asks readers to consider: “In the midst of progressive political movements, who is made invisible?” And “what are the repercussions of such invisibility, particularly that of women, people with disabilities, and the LGBTQ+ community in the post-colonial socioeconomic context of 21st-century Korea?”

As you know, MV Sewol Disaster refers to the sinking of the Sewol Ferry off the coast of the island of Jindo on April 16, 2014 294 passengers and crew members lost their lives, many of were students of Danwon High School in the city of Ansan. In the investigations following the disaster, it was revealed that the sinking was not an unavoidable tragedy, but rather the result of greed, corruption, and negligence from the Korean government, elected officials, and the most elite members of society.

For those of us who were in Korea during the Sewol Disaster, the disaster and itself were filled with sights, sounds, and feelings that we will never forget. From the news coverage of devastated parents waiting for updates in a de-facto shelter in a high school gymnasium, to the flowers and snacks left on the school desks of the victims by their surviving classmates, and the overwhelming feeling for collective sorrow that overtook the entire nation – as the grief of the victims’ families became our grief too, we knew that as a society and a country we would never be the same again.

Despite the national outcry at this preventable and avoidable loss of life, the factual and emotional truths of the Sewol Tragedy quickly became buried in the colonialsm, racism, and xenophobia of the Western press that swarmed to Jindo Island and Ansan. the eleven-year anniversary of the disaster. Yet, the unanswered questions of those left behind– notably the families of the victims, the volunteer civilian divers who recovered the victims, the citizens of Ansan, and the Korean public at large have been silenced, much like the view of the mukja. dd’s Umbrella zooms in on two individuals who find themselves abandoned by view of the mukja and explores the ways in which they navigate the simultaneous grief occurring within their personal lives and the grief that occurs on a larger scale in the wake of a national disaster.

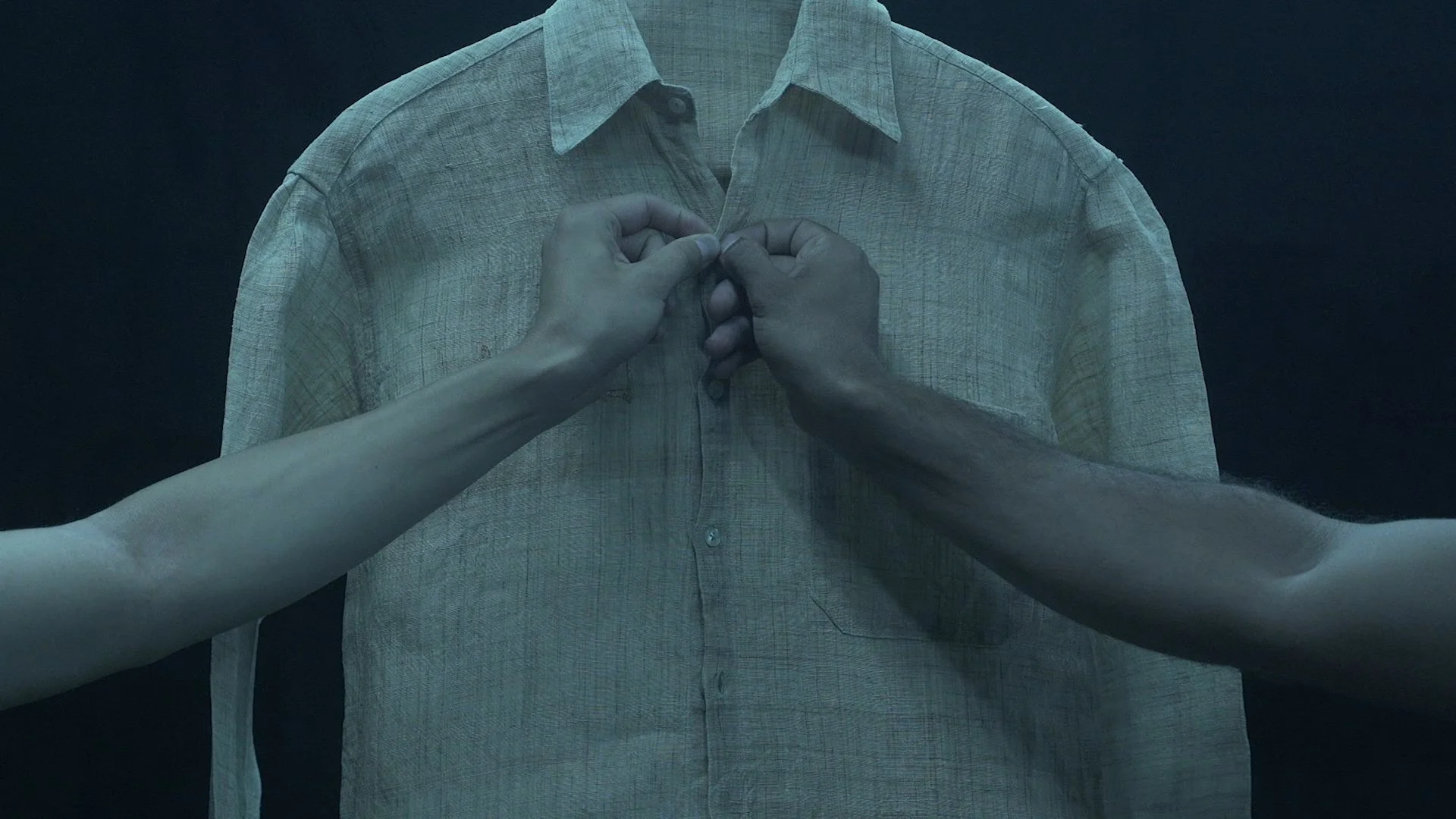

Kang Seung Lee - Lazarus (2023), Single-channel 4K video, color, sound, 7 min 52 sec

Courtesy of the artist, Commonwealth and Council, Los Angeles; Gallery Hyundai, Seoul; Alexander Gray Associates, New York.

Image description: Two hands are clasped together tightly. The upper hand wraps its thumb and index finger around the lower hand’s thumb, sticking out the other three fingers; the lower hand grasps onto the other.

In the first part of the novel, ‘d,’ readers are introduced to d, a gender Seoulite who struggles to reckon with unexpected passing of their cherished partner dd. In the opening chapter of ‘d’, d recalls the time dd insisted they borrow their umbrella on a rainy day. And through this small gesture of kindness, “in dd, d had found their sacred object.” Following dd’s untimely death, d begins workin as a part-time delivery person at Sewoon Market – a forgotten electronics market whose vendors struggle with a lack of business and the looming threat gentrification. Sewoon Market, too, finds itself in the view of the mukja that is neoliberalism and the municipal government. When d and their friend Park Jobae later venture into Seoul’s Jongro District on the anniversary of the Sewol Disaster, they find themselves unable to navigate the city due to police barricades listen to the shouts of political protesters they realize “the voices of the people here will never reach beyond this interval, this vacuum… followed the course determined by the barricades like a couple of meek sheep. And washed up here, like sediment…. This is it, isn’t it?”

‘d’ is written , narrative, on the protagonist d. This allows for a slightly zoomed-out, bird’s eye view of d, giving not only insight into the motivations of d, but also to that of the world they inhabit. For example, as d and Park Jobae walk through Jongro on the anniversary of the disaster, the sights and sounds of central Seoul seem to swirl around them as “people walk past with white chrysanthemums…POLICE signs facing the throng…tall buildings buttressed by snazzy outlets like Keumkang Shoes, Uniqlo, and Giordano” and “people sauntering out of bars to head home or to the next drinking hole.”

The second part of the novel, ‘There Is Nothing that Needs to Be Said,’ is written from the perspective of writer Kim Soyoung as she sits at her kitchen table the morning of President Park Geunhye and to finish writing a story “in which no one dies.” Just as d finds comfort in the object of dd’s umbrella, Kim Soyoung in the form of books” that no two copies of the same book are truly the same because “their copies will be as distinct as other people’s experiences of yesterday are distinct from mine.” Kim Soyoung’s love of storytelling and the books that she has read is the lens through which she reflects on her relationship with her partner Seo Sookyoung, their child Jung Jinwon, and her younger sister Kim Sori. By alluding the works of authors such as Antoine de Saint-Exupéry, Jin-Sung Chun, and Nietzsche, Kim Soyoung attempts navigate difficult questions surrounding the same-sex parenting of Jung Jinwon, the gradual loss of her eyesight, the sexism and misogyny she experienced at political protests as a university student and later on at workplace, and her search for language to describe the relationship between herself and Seo Sookyoung to others. Like d, Kim Soyoung and Seo Sookyoung are also in Jongro on the first anniversary of the Sewol Disaster and they find themselves at the mercy of the view of the mukja. They attempt to go to Gwanghwamun Square to lay chrysanthemums at the memorial altar for the victims, but they are unable to do so because of police barricades. Kim Soyoung recalls that “we gazed up at the night sky glittering with city lights, until we realised the strangeness was due to the stillness around us. It was a Thursday night but the usual glut of sounds that fill Gwanghwamun and Jongro were gone.” Therefore, it is not just Kim Soyoung and Seo Sookyoung, but all the Sewol Disaster mourners that find themselves in the view of the mukja that is the city of Seoul.

In contrast to the third person narrative of ‘d’, ‘There is Nothing that Needs to Be Said’ is written in voice, which makes this section of the dd’s Umbrella feel diaristic and contemplative. In addition, as Kim Soyoung’s recollection of events is at times foggy or difficult to retell due to the emotions attached to them, her narrative collage of faces and feelings. For example, when pondering the strained relationship with her younger sister Kim Sori and their difficult she says “We talked about this and that I don’t recall all of what we discussed over the subsequent months, but I do know we barely mentioned the Sewol sinking. We talked about everything but that.” It is through Kim Soyoung’s narrative that we see that she is perceived through the view of the mukja even in the complex relationship with her own sister.

Kang Seung Lee - Lazarus (2023), Single-channel 4K video, color, sound, 7 min 52 sec

Courtesy of the artist, Commonwealth and Council, Los Angeles; Gallery Hyundai, Seoul; Alexander Gray Associates, New York.

Image description: Two topless, male individuals lie horizontally on the ground, in opposite directions, against a dark backdrop. Each man’s head is rested on the other’s shoulder.

dd’s Umbrella is neither plot nor character-driven. Instead, the novel offers a reading experience that feels atmospheric and meandering. Coming in at 245 pages of quiet and minimalistic prose, dd’s Umbrella is both an accessible and introspective read that attempts to answer very painful and nuanced questions to which there are no clear answers. It is also to the credit of both Hwang and e. yaewon that careful attention has been made to be respectful of characters’ gender identities, using they/them pronouns for d and Jung Jinwon. This is not something that is overtly explained or made a central characteristic of either d or Jung Jinwon is simply a part of the people they are.

This is, however, not to say that Hwang’s prose or e. yaewon’s translation lacks description or detail. Rather, the north of the city of Seoul functions as a character in and of itself due to Hwang’s careful and intentional attention to setting. Hwang makes it clear that the world of dd’s Umbrella is not the sleek and curated version of Netflix Korea. Rather, it is semi-basement apartments, goshiwons, the dimly lit Sewoon Electronics Market, the backstreets of Jongro 3-ga, and finally the bitterly cold Candelight Protests in Gwanghwamun Square in the winter of 2016 that the characters not only inhabit, but also respond to as a living and breathing organism.

In dd’s Umbrella, Hwang asserts that even during times of progress and change, there are still voices that remain unrecognized and unheard. The years following the MV Sewol Disaster is of course not the only instance of left-wing outcry in Korean. In fact, it is the resilience of Korea’s youth across generations that makes the Korean people swell with pride. And given that President Yoon Suk Yeol declared martial law on December 3, 2024 and the streets of Seoul have since been filled with K-pop light stick-illuminated protests that are remarkably similar to that of dd’s Umbrella, this message remains more relevant and important than ever before. Political protest is, of course, a collective voice. But what voices are lost in such collective outcry?

In the early hours of December 19, 2024, exactly 24 hours before this article was submitted to the editors of SUSPECT, President Yoon was arrested on charges of insurrection, making him the first sitting Korean President to be put under arrest. Shortly after, Yoon’s supporters stormed the Seoul Western District Court, not only breaking into the court building and destroying its offices, but also assaulting police officers. The people of Korea awoke to the news of the riots that had occurred overnight, leaving the entire nation shocked by the scenes that were eerily similar the the January 6th Insurrection. And as someone who was born during the dictatorship of President Chun Doo-hwan, the recent arrest of President Yoon marks a strange full circle moment not only for myself, but for all of Korea’s millennial generation. It goes without saying that the themes of dd’s Umbrella are inseparable from not only Hwang, e. yaewon, and the political landscape of the late 20th and early 21st centuries, but also Korea itself.

Hwang was quoted in 2018 saying “the fundamental basis of revolution is worrying about whether the person standing next to you has an umbrella when it starts to rain and you open your own.” And those who lack an umbrella are also those who exist in the invisible pockets of the silenced within a larger movement of collective mourning. Just as dd and Kim Soyoung mourn the victims of the MV Sewol, the people of Korea today not only mourn the recent Jeju Air Disaster at Muan Airport, but also the near-dissolution of their democracy. And perhaps similar to those in dd’s Umbrella, we in Korea now find ourselves mourning a hypothetical future that remains unknown. Korea now feels as if it is in a state of limbo – a strange simultaneous grief and that is somehow combined with an unnwavering belief in Korean democracy. Dd’s Umbrella argues that for each moment that remains alive within the history books, there are individual stories that will be remembered and there will be those that remain unheard – but to the people to who those stories belong, they are the way in which the experience the world.

In the uncertain times that we live in and the uncertain future that we face, dd’s Umbrella asks readers, “in your life is made invisible in the view of the mukja?” And perhaps it is then that like dd, we can offer them an umbrella.

If you would like to support the families of the MV Sewol victims, please visit 416sewolfamily.org

Kang Seung Lee - Lazarus (2023), Single-channel 4K video, color, sound, 7 min 52 sec

Courtesy of the artist, Commonwealth and Council, Los Angeles; Gallery Hyundai, Seoul; Alexander Gray Associates, New York.

Image description: A beige-colored, collared shirt is hung against a black background. Two hands, belonging to two different individuals, reach in from the left and right sides of the frame respectively. Together, the hands button the shirt.

Taeyeon Song (she/her) is a Korean writer, performer, and doctoral researcher who lives in Seoul. She loves cup ramyun, her dog Emma, Stephen Sondheim, learning Korean Sign Language, and getting angry about colonialism. This review marks her third published article in Singapore, for which she is eternally grateful. Instagram: taylor_taeyeon

*

Kang Seung Lee is a multidisciplinary artist who was born in South Korea and now lives and works in Los Angeles. His work frequently engages the legacy of transnational queer histories, particularly as they intersect with art history. Lee’s work has been included in international exhibitions such as the 60th Venice Biennale (2024); New Museum Triennial (2021); and Gwangju Biennale (2021). His work is in the collections of Hammer Museum, Los Angeles; Leeum Museum of Art, Seoul; Los Angeles County Museum of Art, Los Angeles; MASP, São Paulo; MMCA, Korea; Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York; among others.

In Taiwan Travelogue, ‘twinned souls… are at once lost, but also found, in translation.’ A review by Eunice Lim.