Char Siew Crossroads

By Emily Perera

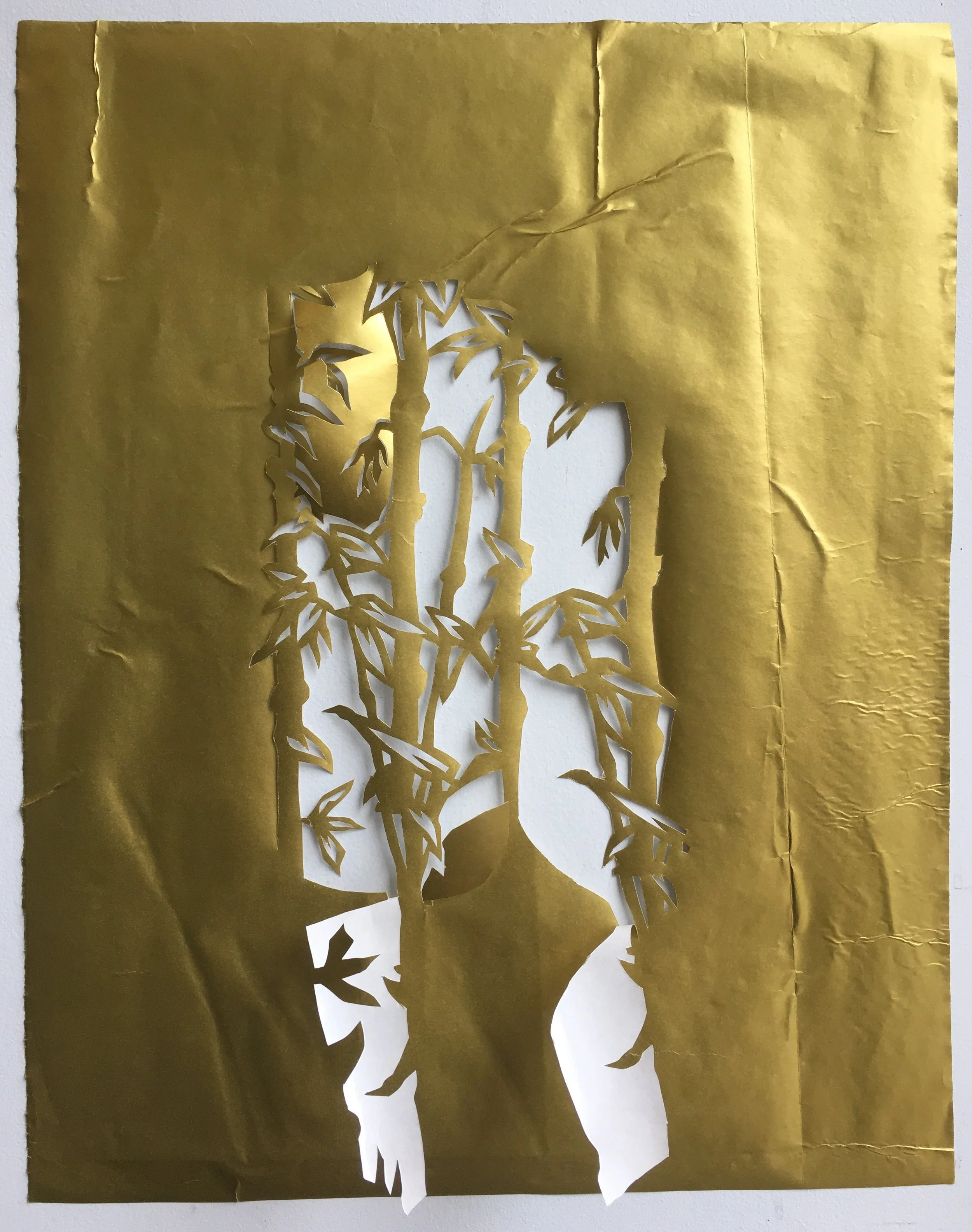

Geraldine Kang - Untitled (2015), Image courtesy of artist

Image description: The photograph shows the exterior corner of a building. The two walls that form the corner meet at a right angle in the middle of the photograph. The wall on the left is painted white and the wall on the right is painted light-blue. Spanning across the corner is a rectangular frame in the shape of a window, filled in with paint that matches the colors of the walls. A light-blue window ledge rests on top of the frame. A thin pipe painted the same colors as the walls runs across the building. In the right background of the photograph there is a darker-blue wall with partly visible doorways. On the left side of the photograph is an outdoor air-conditioner unit.

There was a Chinese boy mummy was gaga for back in the day, I say.

***

Grease on the floor. The moon is a fingernail in the sky and you lead me to a table. A rag with 安早君祝 (I don’t know what that means) printed on it swipes across it and then bright orange shirt leaves.

I come here a lot, you say. The char siew rice is damn good. Really ah, okay I get that too.

I have changed my voice for you. The accent feels thick and glutinous on my tongue.

Come, I buy for you. Sit down.

I shuffle about in my seat. Behind me, two pot-bellied men are booming in a Chinese dialect. Mando-EDM plays in the background.

This is the hawker centre that I used to speed by when was walking past; holding my breath for second-hand smoke. At home, my mother would buy nasi lemak from the Coconut Club or Crave. Sayang, eat good food. She would then play Class 95 and cook us all aglio olio for dinner. Is everything I eat a mass market commodity?

Clear soup sloshes in the bowl. You have two sets of char siew rice stuffed on one tray and you walk slowly to me, trying not to spill the soup. Man in a Bossini shirt stops to let you pass. You place the food on the table slowly, like setting down a baby. Looks good ah?

Your face is florid and you look like a little boy.

You took two sets of chopsticks and spoons with you. I have never eaten rice with chopsticks, but I decide not to tell you. There is soya sauce in a flimsy plastic dish and it is the colour of your eyes.

We eat in silence at first. The char siew rice really is as good as you say. It's sticky and sweet, and the rice feels fluffy on my tongue. I feel strangely vulnerable – eating the same food as you, fuelled on this febrile air of something new. It's like being naked in a white-lightbulb, ceiling-fanned hotbed.

Geraldine Kang - Untitled (2015), Image courtesy of artist

Image description: A large, indoor marketplace with a broad, central aisle is lined with different stalls on both sides. In the center of the photograph, a man in a purple shirt and black pants walks forward with his head slightly down. Tall columns line the center of the market’s aisle. Many shoppers are walking and browsing the stalls. In the right background of the photograph, a storefront has two big, red lanterns hanging in front of it. Several shoppers stand in front of the store.

Chopsticks feel foreign in my hands. Raspy screech as one of the hawkers pulls down the metal front of his stall.

What time is it?

You break the silence: Wait, like legit not to be offensive or what lah, but… I didn’t expect you to be like? This?

How so?

I dunno, just your vibes yaknow? You seem very urm… atas?

I'm not! See – I'm eating in a hawker centre!

So… you think hawker centres are for the low class, is it?

I don't know how to respond.

I polish off my rice before you. I'm hungry, and I haven't eaten all day. I hesitate when I get to the soup. My mother told me how this kind of soup is MSG-laden, some toxic enhancer from hell that will leave me seedy and debilitated. I don't know much about you, but I don't think food wastage will further this humble narrative I am trying so desperately to push. So I make conversation to stall the issue at hand.

What's your family like? Okay, I guess. I have two older brothers. Do you like being the youngest child? Shrug. Okay, I guess. What are their names? Keng Hean and Keng Hee. So why are you called Keng Keat? Why not KH, like your brothers? I was born at KK hospital. Wait, legit? Yah, legit. Laugh. It's kind of funny. Where were you born? Mount Elizabeth. Oh.

You ask me if I have a curfew. I do; it's at 10pm. But I don't think I will tonight. Life is uncertain, and I'm 17 in a hawker centre with a boy I just met.

Slick countertops and you smile at me like you used to know me. Maybe we're both the same kind of lonely, walking away into the day or the night. Reach into my bag and I discreetly push the side toggle on my iPhone up, the one that turns it on silent mode.

I ask if you have a curfew. You laugh at the absurdity of the question. No, but I wish I did.

Why? I dunno... I guess when there are rules, it's like someone cares for you lor.

The way you say it – it feels like I broke something. I bring the soup bowl to my mouth and drink it all at once, like swallowing a river.

Geraldine Kang - Untitled (2015), Image courtesy of artist

Image description: In front of a store filled with shelves displaying a variety of household products, a woman in a floral-patterned dress and a purple scarf pushes a baby stroller. A child sits in the stroller, partly obscured by a cardboard box in the foreground. In the background of the image, a person in a red shirt and with a black bag is picking an item off a shelf. On the right side of the image, a man and a woman seem to be examining a product.

***

We met in a warehouse at Jurong. I found the job on a telegram channel – TEMP WAREHOUSE ASSISTANT LIGHT PACKER 2 MONTHS URGENT!! There was a lollipop, apple juice and star emoji accompanying the heading. It paid $10 an hour, and I was dead broke.

I flunked my J1 promos – three Es and one D, getting to J2 by the skin on my teeth. Didn't matter that I was in Singapore's leading institution or that I really had tried – my allowance was cut off for the holidays, and here I was, restoring livelihoods one pull of my tape gun at a time.

The morning of my first day dawned hot and buttery, burning with the chromaticity of the Singapore sun. My supervisor took a quick glance at me and left me there. I think people look at me and see a Malay girl. Or maybe they don't. But what is a Malay girl? Does a Malay girl like her carrot cake fried black or white? Is a Malay girl pretty? Does she score better in English or Malay? Am I a Malay girl?

Then you came up to me, Chinese boy with box-dyed hair and in slides. Are you new? Yeah.

You wordlessly pick up a flattened piece of cardboard, fitting the flaps together with surgical precision until they overlap into each other, puzzle pieces into origami, tapeless making of a box. Try, you tell me. I fold the flaps, but each time I think I’ve got it down, they pop out of each other, dismantling the box. Three minutes in and my face is red because, fuck, it’s my first day and I can’t even put a box together, and fuck, you’re kind of cute actually. You laugh and take my hand in yours, guiding me and by the end, I have constructed a box, bashed and crumpled at the bottom but who looks at the bottom of a box? I wait for you to tell me your name, but you don’t.

Later, I hear another worker call you Keng Keat. Keng Keat. The name feels hard on my tongue, travelling from the back of my mouth right to my teeth. It feels like a rattan fan and a zinc roof. Keng Keat. Keng Keat. Keng Keat Keng Keat Keng Keat Keng Keat Keng Keat Keng Keat Keng Keat

Keng Keat.

***

Scratch of cardboard against cement. Metal racks and people shout in a language I don’t understand. Pair of diamond earrings on you and they look like teardrops.

Thump. Box hits the ground.

So… you’re taking A levels, is it? Thump.

Yeah. Laugh. I flunked my promos, though.

For smart kids like you, a fail is not a fail lah.

Chill. High-pitched screeeeeeeeeeeeeeeeeeech. We cover our ears.

What about you? What JC are you in?

I’m not in JC. Poly? No. I’m in sec five.

I can fold boxes quite well now. Slip, slip, slip. Neatly intertwined flaps, each a part of each other, disjointed and whole. Leaves in a bird’s nest. The blonde in your hair. Things come together sometimes, legato strings of sound and you can try but you can’t shake it off.

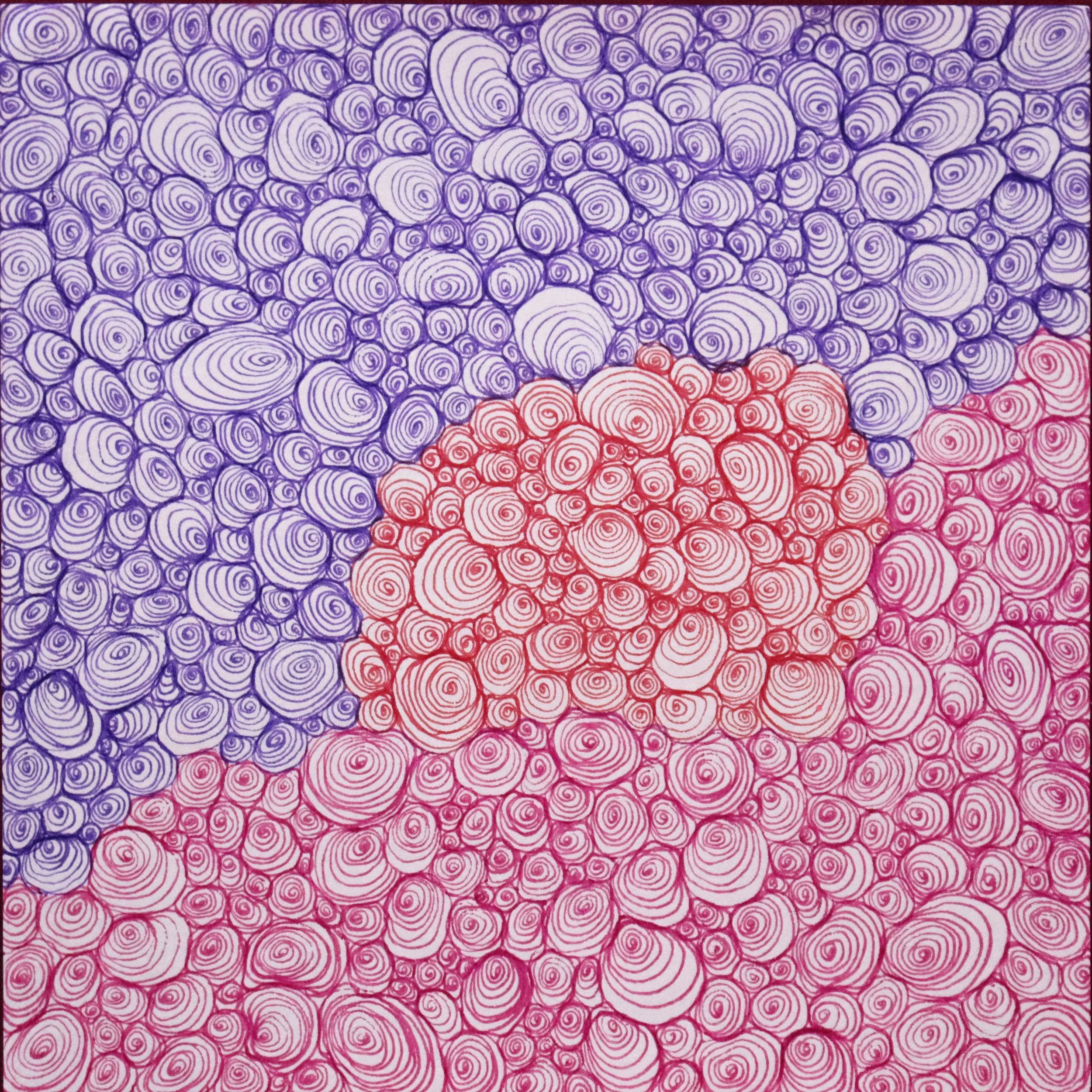

Salty Xi Jie Ng - Untitled (2015), Image courtesy of artist

Image description: Dozens of tall houseplants are lined horizontally across the photograph, against the backdrop of a multi-storey, public-housing building. The plants—mostly in terracotta pots—are of various heights, sizes, and species, and are placed closely together to form a lush, green conglomerate. In the background, two small, red lanterns hang from the ceiling.

***

You tell me about how you struggle with English in school. I say not to brag, but I have never got below an A1 for English before – want me to tutor you after work?

You’re bragging. I’m not, okay? Offer is on the table. Huh? What does that mean? I’ll teach you after work. Sighhhhhhhhhh. Aiyo, whatever lah. You’re smiling. No I’m not. You like spending time with me. I do.

After our daily char siew rice (char shao fan in Chinese, I know that now), we go to a void deck. Metal letterboxes and a bright white spot from the ceiling light. I can see the tiny scratches, rounded lines made by keys, brass against steel, patterns like the capillaries in my father’s eyes.

You say you struggle the most with paper one, the continuous essay. I give you a past O-level prompt: Describe a time where you bit off more than you could chew. What happened and what did you learn?

How would you answer this? Maybe… the time my mum was sick and I had to cook… and everything. And then I failed a test. What does failing a test have to do with it? I had to stay back for remedial every day. Oh. Didn’t you ask for help? I thought I could handle it. Okay. Let’s write about it together.

We spend two hours writing the essay. I teach you about descriptive language and phrases like the cerulean blue sky. I show you how to vary sentence length and build suspense. We come up with fake dialogue together – Keng Keat, I’m so proud of you, we make your mother say. Are you sure you can handle all your commitments? – we make your imaginary best friend say. You’re attentive, asking questions and writing down things I say. Sweat sticks to your forehead but your eyes are always on me.

You’re learning; but so am I. I learn about how your father left when you were just a baby, and your mother had your oldest brother at 17. I learn about your Star Wars bed sheets and your teacher with the protruding fats. I learn about your brother in NS and the other one working as a full-time photographer. I realise that I love listening to you talk, the sound of your voice and the way I can feel it ebb and flow. It feels like rain – refreshing, like tonic.

You’re close to me and I realise that I can feel your breath on my face. The night is hot and muggy, and you radiate heat. By the time the lesson is over, my heart is racing. I look at you and your pupils have gone dark.

Zap and the lights go out. Power outage, I whisper. The moon is a pale golf ball in the sky. I lean against the letterboxes and start to unbutton my shirt. You don’t protest, and we stay there for a while, two shadows in the dark.

***

We settle into a routine. Swoosh. Slide a cardboard box to you. Dull sound of plastic hitting plastic, eat char siew rice with chopsticks and finish the clear soup every time. Thank you auntie.

At the void deck for my free English tuition. You pronounced it as tew-shen and I corrected you. Tew-yee-shen, I say. I remember this because when I was younger, my mother would rap my wrists whenever I pronounced a word wrongly. Also, whenever I spoke Malay in public. Insyirah, you can’t make them think of you that way. Okay Ibu. Okay mummy.

After tuition, we would go to the level three staircase (level one and two were too close to the ground) and I would do things with you I haven't done with anyone else. I don’t tell you this, but I have never had a boyfriend. In fact, before you I hadn’t done so much as kiss a boy. After we were done, I would come home, shower, and pray until daybreak. My feet started to cramp up. Allah, please forgive me. He is not Muslim and I am a fool.

One day, after a romp at the staircase, you took out a juul. Want a hit? No, thanks. Why? Vaping. It’s bad for you. Then I’m bad for you. But I’m not.

Salty Xi Jie Ng - Untitled (2015), Image courtesy of artist

Image description: A man in a red shirt and black pants walks towards a multi-storey, public-housing building with a blue sign saying “26” on it. The facade of the building is painted in white and blue; similar buildings are in the background. The man walks on a path between two tall and leafy shrubs. He carries a heavy, bright-red, plastic bag in each hand. As he is pictured in mid-walk, his weight is placed on his left foot, and so his body leans slightly left.

***

It’s quite simple, really. How I found out. It was almost comical in nature.

You’d been strangely busy after 8pm for two weeks in a row. You told her you were working OT, but she called your boss. She came to look for you and two hours later, she decided to start checking the staircases of the HDB flats. Why would she look there? Had you brought her there too?

Tight slap and Hokkien vulgarities. Sting, sting, sting. Your eyes are wide open, the moon still a fingernail in the sky. Hug my bag against my chest. Chinese words I don’t understand. Were you cheating on me when I was never your girlfriend? Things get convoluted.

She grabs you by the hand and I feel a pang of guilt for what you will surely go through. And then she takes a long look at me. She speaks in English, for the first time. Know your place. I know what she means, so I say nothing. And then you are swallowed, swallowed by the money plants in the corridor, incense stick and the beep of lift buttons.

I can still taste the char siew in my mouth. I go home and google the effects of too much MSG.

***

Do you ever hate being Malay?

I take a long sigh. I look up at the black dust that has gathered on the ceiling fan.

Then down at my wedding ring. Stroke my cat, who curls up in my lap and then slips under my arms. My neighbour is cooking fish curry again. I wonder where my Quran is.

There was a Chinese boy mummy was gaga for back in the day, I say.

Emily Perera is a 17-year-old literature student studying in Singapore. Her passion for words has led her to do crazy things, like not taking math in JC and dreaming of making a living as a writer. This is her first published work.

Salty Xi Jie Ng (b. 1987) co-creates semi-fictional paradigms for the real and imagined lives of humans within the poetics of the interdimensional intimate vernacular. The Handbook of Everyday Secrets was a project about reimagining everyday life made in collaboration with people from the Bendemeer-Boon Keng community at Kallang Community Club in 2015. Geraldine Kang was an intimate onlooker to the project, responding with text and images.

Geraldine Kang uses art as a means of introspection and as a tool to negotiate identities within physical and psychological spaces. She sees art as a platform to express the complexity of difficult topics and issues. Using a mixture of photography, writing and objects, she creates installations that address a range of topics from family, community, and mental illness to site-explorations of the undercurrents and ambivalences of familiar places.

Geraldine holds an MFA in Fine Art from the Parsons School of Design (The New School) and has exhibited her work both locally and internationally with solo exhibitions at the Institute of Contemporary Arts Singapore and NTU CCA Singapore. She has participated in group shows at the ifa Gallery in Berlin and Stuttgart, ONESITE Art Festival in Taiwan and the Tokyo Photographic Art Museum. She was awarded the 2011 Kwek Leng Joo Prize of Excellence in Still Photography and participated in photography platforms such as Kuala Lumpur International Photo Awards, Photographer’s Forum, Px3, the Jimei x Arles International Photography Festival and the Singapore International Photography Festival. Geraldine is currently a full-time art educator.

If you’ve enjoyed reading this article, please consider making a donation. Your donation goes towards paying our contributors and a modest stipend to our editors. Singapore Unbound is powered by volunteers, and we depend on individual supporters. To maintain our independence, we do not seek or accept direct funding from any government.

‘But later… we didn’t talk about love. We talk about the land and its people.’ – a short story by Kaushik Ranjan Bora, translated from the Assamese by Aruni Kashyap.