Gai-gai

By Casper Ho

Lai Wei-Yu - Toy Gun (2019), Acrylic and charcoal on canvas

Image description: On the right side of the image, a youthful-looking figure wears a helmet, a brown jacket, and checkered shorts. The figure points a rifle towards the left side of the image. Colorful, squiggly lines seem to shoot out from the rifle.

There are colorful banners stretching across the image, against an entirely dark background. On the bottom left corner, four figures with blank expressions stare ahead. There are small pots of plants along the bottom of the image. The painting is rendered in fine lines and has a chalky texture.

“Nicholas, put on your shoes.”

“Wait.”

For gai-gai today it will be a bit different for me. Madam Quek has asked the class to fill up a journal book describing our two-week holiday. It is already the middle of the second week, and I have only one page filled. 2 July 2023 – Mummy made nasi lemak today for dinner, but I kind of like the stall one better. I shouldn’t tell her this or she will FREAK.

But that will not be enough. I messaged Yew Huan and he told me he’d already done half the book. I asked for pictures so I can get ideas for what to write but he didn’t give them to me, so I don’t think I’ll talk to him on the first day of school so he’ll know I’m angry at him.

Nani gets in the back with me, I tell her to put on her seatbelt, and instead of doing that she goes, “What’s that?”

“Journal book for my assignment.” I like saying “assignment” because it makes the homework seem more important. I wonder if I should tell Madam Quek that as an opening line, it would be an interesting “hook”, as she calls it. As I’m pondering on this, I don’t see the danger of Nani unsheathing a crayon from her arsenal of colour pencils and oil pastels. She presses the tip of it onto my clean page, forever marking it with the ignoble emblem of an amateurly-drawn purple fish with five fins. “Nellie, why did you do that!” I scold her. “Now my teacher will think I did that.”

“It’s nice,” she tells me.

“It is not…” I whine, trying to scrub it with my thumb, smearing it even more.

“Hey, hey, why are you two fighting,” my father calls from the front.

“We are not fighting,” I speak this blatant untruth, not wanting to be in trouble, but the laughter in my voice betrays me.

How am I to write this? Can I write this? I don’t know if it is right to tell my teacher that I am angry, I don’t know if she wants to read that. I try to recall what she said that day in school, “I will be excited to hear about stories about your holiday, where you went, what you did.” I frown in confusion. I have not gone anywhere, I am still in the car. I did not do anything, my sister did. But still, I am angry. The formula does not add up. I don’t know how to write about this.

I frown for a bit longer at the empty page, feeling a sense that I am losing what I’d intended to write, feeling it hard to catch it back in my memory, like they are slippery cloths being snatched by the wind out of the car window as Dad whizzes past the other cars so he can show them he is faster. “Slower,” my mother tells him. He shakes his head, says it is okay.

It is going to be a fun day today, we are going to the shopping mall. Last night was the first time I could not sleep properly. My head brimmed with the thought of seeing the new dragon movie, and so I felt like I was drowning, like I couldn’t breathe from all this excitement. It made me anxious to look forward to something so much. And I wondered about this feeling, but I could not wake my mother or father up, because it was well into the night and it was only me who was wide awake in the darkness.

I think I finally have something to write but when I get my pen on the paper I realise I don’t know what I wanted to say. I am curious about this feeling, and I wonder why I felt so scared, but I don’t think it would make sense for my teacher to read that. So I just write, I am excited for the movie today that I am going to watch with my family. My mom, my dad, my sister, Nellie.

I remember more of what Madam Quek instructed us. “Be sure to take in the sights and scenes of your holiday. If you are going to the beach, think of what to describe there. The seashells, the seashore, the vast water.” We stop at a traffic light and I look out the window to see many men walking in a line at the side of the road. Tailing behind them is a man that is maybe not a part of their clique, he is older-looking and in more tattered clothes. I feel something burgeoning in my chest, like a pulling guilt or sadness. But on top of it is a confusion for what I am seeing. This is not a beach, it is a road. And I can’t say the water is nice or the sky is nice, I can only look at this man and see him beg one of the boys in front of him for some spare change. I feel bad about that. And I feel even worse to think that, once the car starts moving again, I will forget he was ever there. I don’t know how to say this to Madam Quek, so I look away from my journal book, hiding this guilt.

And then we enter the tunnel. This is my favourite part of the drive usually. The car becomes dark and then the orange lights flicker over us, like I am at one of the concerts Nani and I watch American teenagers on TV go to. But they are too fast for my pen to catch, and before I can write about how fun it is, we are out of the tunnel. My father stops under a huge roof in the middle of the road, where he opens his window to pay a man to let the barrier come up and let him pass. I think how fun it is to work as that man, to stay in a little hut in the middle of the road and eat and receive money. Without this man there will be no way we can pass. Then my mind wanders. I wonder what this man’s life is like. I wonder about the houses that we see disappear in seconds when we pass by them, all inhabited by working people and children like me. Again, I want to catch this thought. But I have lost so many, I feel it would be awkward to start on this one, so I don’t bother. I am a bit frustrated, but it is okay. We haven’t even reached the shopping complex.

It is amazing, I have been here many times but every time I am excited, wondering what awaits me. I forget the book in my lap. When we are looking for parking, Mum says “Pray for parking.” And I don’t write this down, because Madam Quek might find it funny, and when we miss one spot when Dad wasn’t fast enough, my mother scolds him and makes a big hoo-ha, and they’re both making big hoo-has. “So clever on the road to go fast, but so soft here.” He shouts something back at her, and I can feel a sort of swirling in my head, I tilt my head slightly to my right shoulder to stop the sound. My journal has fallen out of my lap, my hands holding onto my ears now, and so I can’t write this, but I don’t think I’d want to. Because it’s weird for a family to be like this, and Madam Quek will ask, because it’s not normal.

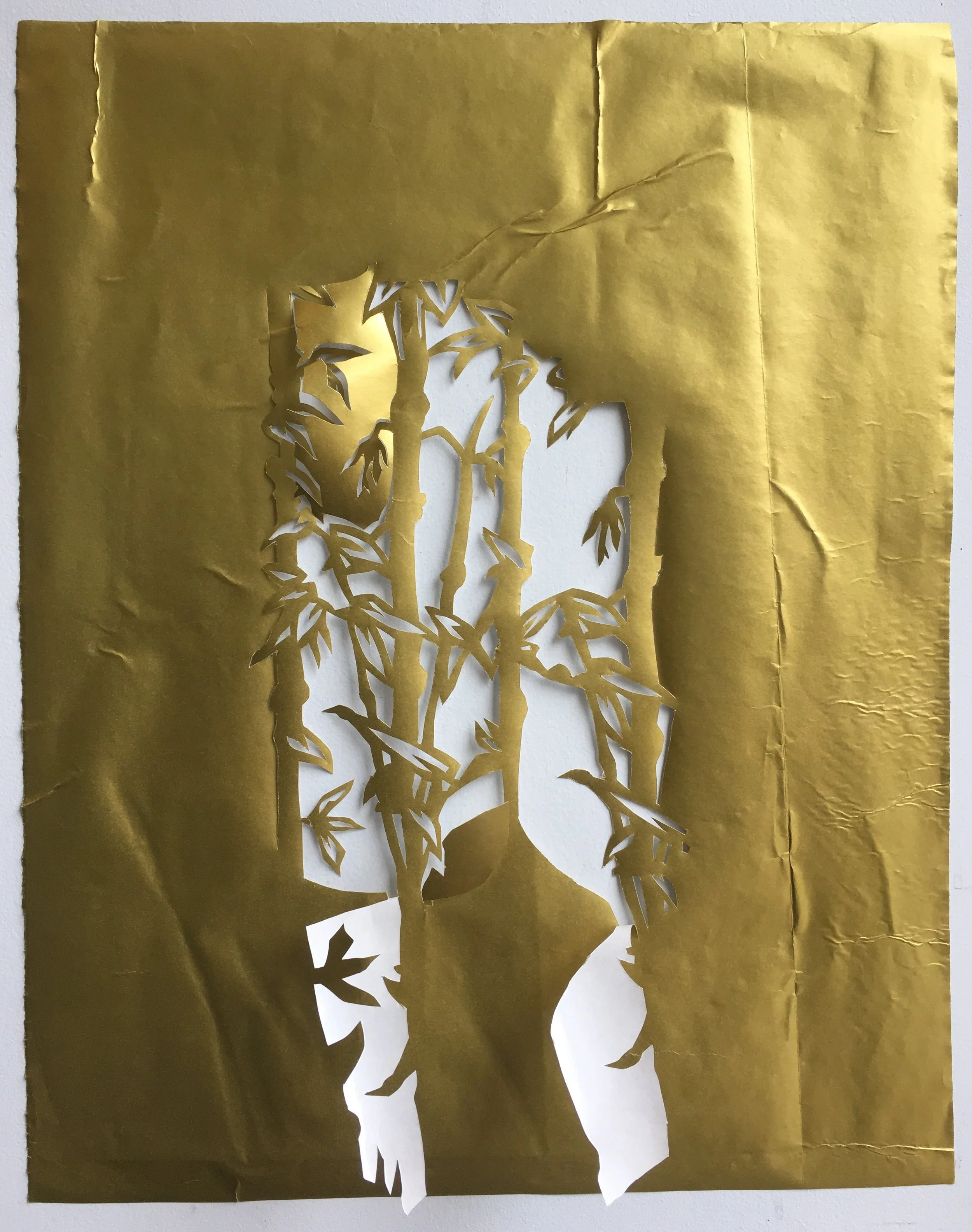

Lai Wei-Yu - On The Way (2012), Acrylic, crayon, and charcoal on wood

Image description: The image features two figures depicted in mid-action in the foreground. The left figure has red hair and wears a black-and-orange dress. To her right is a short-haired figure in a colorful, striped shirt, blue shorts, and red boots. The two figures are holding hands; their facial features are rendered abstractly in simple lines. They seem to be running on a blue path. On the left side of the path are lush green trees rendered abstractly. On the right side of the path is a row of bare branches. A third figure in a checkered shirt crouches down on the ground on the right side of the image, holding their head in their hands.

In the shopping complex Mum is very angry, she keeps a distance and is silent, when I look back at her she says “Go, go with your father.” She’s angry. “Look at how fast he’s walking. Acting like he did nothing wrong.”

And when I go to Dad, he says, “Hurry up la, why so slow.” So they are both angry, and I must be careful.

The movie tickets are handed over, but I don’t feel very fun anymore. Something has changed. I realise that I’d left my journal in the car, and I’m glad for it, because it would be too much trouble to explain this feeling.

Mum and Dad are still not talking, and I hope by the end of the movie they will get along. I hope that in the darkness they forgive each other somehow, and then it can feel okay again. The movie has some funny bits which I like, and the part where they fight makes me feel like I am flying. The hairs on my neck stand, and it makes me want to get up and follow what he is doing. I feel cool with the music.

When the movie becomes emotional and talks about a family’s love for each other, I start to feel embarrassed. I don’t want to look at Mum or Dad. I know this is not them and they might be wondering what the movie is even talking about.

Anyways, I was right. They begin to talk slowly to each other. It always begins with Dad’s first question, “Where you want to eat?” And Mum will quietly say some place, and then we will go. And then he will bring up a question about something, this time it is something we see on display at a shop’s window. “This one you wanted, right?” and Mum says, “No, this one’s a different cut.” Quietly, still, until they ask enough questions back and forth while walking side by side shyly and then they laugh when it is enough, and Mum says while giggling, “No, he wouldn’t do such a thing!” because they’re now talking about some man they know that I don’t know, and Nellie asks me who’s this man, and I say “How I know.” I only know that they are okay now and I can feel okay too.

“You liked the movie?” Dad asks me at the restaurant Mum wants to eat at, a Korean fried chicken place. “Don’t only eat the skin.” Mum drops a chunk of chicken flesh into my bowl as I shake my head, and then a ball of sticky rice by its side. Dad says, “It has a good lesson to learn.” And I don’t know the lesson but I just nod.

We go shoe-shopping, Nellie needs new shoes. “I want one for school and one for going out.”

“So many for one small girl,” Dad says.

“What’s wrong? How many does Nicholas have? That one you never count?” Mum doesn’t look at me when she uses my name, but she said it angrily so I am a bit confused. But she doesn’t notice my staring.

“That one different.” Dad’s voice weakens a bit, this is his voice when he wants to end the conversation.

“How is it different?”

He quickly plucks a pair of yellow slippers from a rack and lets it go on the floor in front of Nellie. “Girl, try this one, see nice or not.” And Mum usually falls for this trick to keep her quiet by distraction, or maybe she is also tired. They are both tired of each other at some point.

“These are slippers. I want the white shoes.”

“The Converse?”

“No the big one.”

They go on as I sit and stare, making sure with my mind that nothing goes wrong, that nobody starts to scream. I keep on looking at Mum’s face, a bit annoyed, tired, yet alert.

After that we are done. Nellie gets her shoes. I get an ice cream cone that I have to finish outside of the car.

I find my journal abandoned on the floor, having hid under Dad’s seat. I get it out and open it, I think of what to write, but nothing comes. I have forgotten. On the silent ride back, we bump up and down and so does my pen, I write down with up and down lines making up my letters, We ate lunch at a restaurant and bought shoes for Nellie. In conclusion, it was a fun day at the mall.

Lai Wei-Yu - Family (2012), Acrylic and charcoal on paper

Image description: Four figures—two adults and two children—are rendered in black and white. They are depicted in mid-action, as if they are running towards the viewer, on a blue-green ground with orange lines and against a dark-blue background with colorful specks. The four figures’ facial features, such as their eye sockets, are rendered in shadows. On the left, a child with shoulder-length hair holds onto the shirt of the woman next to her.

Being at the age where one must make choices that certify them a full-fledged adult, Casper Ho finds comfort in looking back on the lot of things that made up his childhood, and often ends up writing stories about them. He’s stopped schooling for now, but he has a job at a restaurant, so he may not spend the entire day writing, but he appreciates every moment he gets to work with words.

*

Lai Wei-Yu was born in Taipei, Taiwan in 1989. He graduated from Graduate School of Fine Arts at National Taiwan University in 2017. Lai Wei-Yu's world of painting is like Fellini's Trojan horse with a hidden agenda. The paintings present strange and bizarre images of urban life, with a fantastical and exaggerated plot, which is full of carnival-like joy. Taking seemingly absurd events, Lai Wei-Yu paints the canvas like Fellini's colorful kaleidoscope with a childlike playfulness, inviting the viewer to enter into the carnival and experience the noise, but in the corner where the sun does not shine, we also see the hopelessness and desolation of life.

If you’ve enjoyed reading this article, please consider making a donation. Your donation goes towards paying our contributors and a modest stipend to our editors. Singapore Unbound is powered by volunteers, and we depend on individual supporters. To maintain our independence, we do not seek or accept direct funding from any government.

In a short story by Yu Xi, translated by Ng Zheng Wei, a gnawing hunger consumes everything.