On Demand

By Marc Nair

I’ve been writing poetry at the Dufferin Grove Farmers’ Market in Toronto for about a year now. On the surface, doing this feels ‘on-brand’ with my creative practice. After all, I have 11 books of poetry under my belt, with a 12th being launched later this year. This market gig sounds like a nice aside, a space for creative expression. Except that it’s proved to be the most constant thing in my life ever since my wife and I relocated from Singapore to Canada. In a depressed labor market with few concrete work opportunities, a job has proved difficult to come by. Poetry has become an unlikely way of earning grocery money, of finding a foothold in the city. Nicole, the market manager, generously offered me a table, two chairs, and a space to ply my trade.

It’s always been natural for me to consider the world through the frame of a poem, to chart experience using a reflexive, place-based approach to what I observe and feel. But here in the market, I am a conduit for other people’s wishes, holding myself open, calling upon an instant noodle version of the Muse to dream up and deliver lines on the spot.

Marc at Dufferin Grove Market . Photo credit Lillian Carcao

Image description: The author wearing a cap, seated at a table in the park writing on his typewriter, green grass and trees behind him.

Armed with a typewriter and a notebook, I set up shop with a hand-drawn sign that reads ‘Poetry-on-Demand,’ taking my place off the main drag of the market alongside craft beer, fruit juice, Tibetan momos, and face-painting by Isabel. Customized poetry is something novel for most people; they find it incredulous that someone can come up with something original for them in 15 minutes or so. Consequently, business is slow at first. People come to the market to buy vine tomatoes and homemade patties, loaves of sourdough or organic duck eggs. Nobody ever comes because they are running low on poetry or because they need to stock up on poetic expression. My first few poems are for friends who come by to support me.

Buying a poem is an act of whimsy, a leap of faith, a “why the hell not” moment. Like ice-cream, poetry is completely unnecessary and yet, utterly delectable to consume. Some people are poets or writers themselves and ask me for a poem as a kind of challenge, I think. Others have a bucolic memory of poetry from school and see it as a keepsake, a tourist trinket. And there are those who see an opportunity. They are completely deliberate in how they ‘use’ the poet: write a poem for my wife’s birthday, my friend is getting married next week, my grandson is turning two, I just started a new job. The poet is on demand for every occasion, but don’t produce anything too twee or trite—the marketeers are sharp cookies. Each poem is reasonably priced at $5 to start, a rate I later raise to $10.

*

This poem is for Tom’s father, who is, according to Tom, losing his marbles.

Forgetting is Overrated

These days, it’s all about keeping things exactly so,

(chalk outlines for the tea cup, a breadcrumb trail

from the park to home). Your body wears a vest

of Post-it notes, careful instructions for various

possibilities, intentions and detours, marking

the constancy of each hour; even though the weather

is mutable, wear these familiar things like a warm

jacket (but only on colder days), otherwise you’ll find

yourself overdressed for the party at the end of the

universe, the one you promised to bake cookies for.

Despite having written hundreds of poems in the past year, putting a price on one still feels weird to me, but I’ve increasingly come to see my work as similar to that of a portraiture artist capturing a likeness or caricature of their customer. It takes anywhere between 15 to 20 minutes to draft the poem, type it out, and give it to the customer in a sturdy envelope. The typewriter, a 50-year-old electric blue and white Underwood 315 which I bought to mask my scrawly handwriting, becomes an object of interest, even envy.

One day, a man stops by my table. “Where did you get your typewriter?”

“On Facebook Marketplace.”

“Really? I’ve never seen one like that. And it’s in good condition!”

“Yes, it works very well for its age.”

“Nice. Is it for sale?

“No, sorry. I’m selling poems, not typewriters.”

“Do you have another one?”

“Ummm, no? I only need one.”

“Well, if you ever get another one in such good condition, I’ll be happy to buy it off you.”

“Uh… sure. So would you like a poem?”

“Not today, thank you.”

*

A poem for Finch, who loves trees.

Where You Are

You are never, ever

ever up in a tree.

You are always, always

where you’re supposed to be.

Sometimes you’re in a cloud.

Sometimes stuck in a crowd.

One time you’re at the beach,

seagulls fly out of reach.

Summer’s a warm embrace,

below a tree; your place.

Sometimes, I write doggerel when no one is around. The clack of the typewriter is its own advertising jingle.

Tale

The interrupted story

is the source of all fairytales:

love and loss around old trees

shadowed by fire

and the carvings

we impose on our skin, languages

that flit by, each containing

their own ending,

ways to be

Every now and then someone comes by to ask for a poem about the market. Maybe it is because they have fallen in love with the vendors and the park itself. The energy of the market is a gentle hum of folk music and organic produce, welcoming regulars and entrancing visitors. Today, it is Serwaah from Ghana who asks for such a poem. After receiving her poem, she opens her picnic basket, leans against a tree, and cracks open a book and a can of beer.

The Right To Be Here

It is only a short walk

to find your community, a generous

gift of people and produce, of stories

that go beyond the augmented chords

and a rising flute solo or freshly

trucked greens from two cities away.

To sit in this park and read

other stories is both a gift

and a gentling ache of sunlight;

fiction is also a way to see,

to conquer the known and

the mystery of being

in this moment.

And then there are the poems that do not get delivered, because people have no time to wait, or they didn’t realize a poem costs money. I write them anyway.

Walter’s New Coat

holds all the secrets of the world,

but it has to be worn

in the right order:

button it evenly,

leaving room for the wind

to stir spirit with hidden words

lift the collar to shield

cloud shifters from pilfering

maps of the way home

fill all the pockets but one,

always leave room for secrets

that are coming into being

One day, Susan asks me to decide between Morris dancing and canoeing for her poem. It is for her husband, Roy. I choose the former and have to do on-the-fly research. Why Morris dancing? I’m not the biggest fan of canoeing, having gotten seasick the couple of times I’ve tried it. I’ve only ever seen Morris dancing in films, but I relish the challenge of writing about something I know absolutely nothing about. Somehow, I manage to dash off the poem by the time Susan returns. Susan doesn’t read the poem when she collects it, so I’ll never know if I got the details down.

Glossary

You hold a glossary of ways to move,

the way forward and back; side to side,

together and separate, praising partners,

moving back. It is all a caper, a hop to hold

and let go, this pattern that’s part

of the whole, the music and the ale,

everybody fielding their feet up and down.

Not everyone remembers the steps in sequence,

but you have always found it easy, laid out

like a map, hands around your love, side

by side, a whole round, before the next tune

begins.

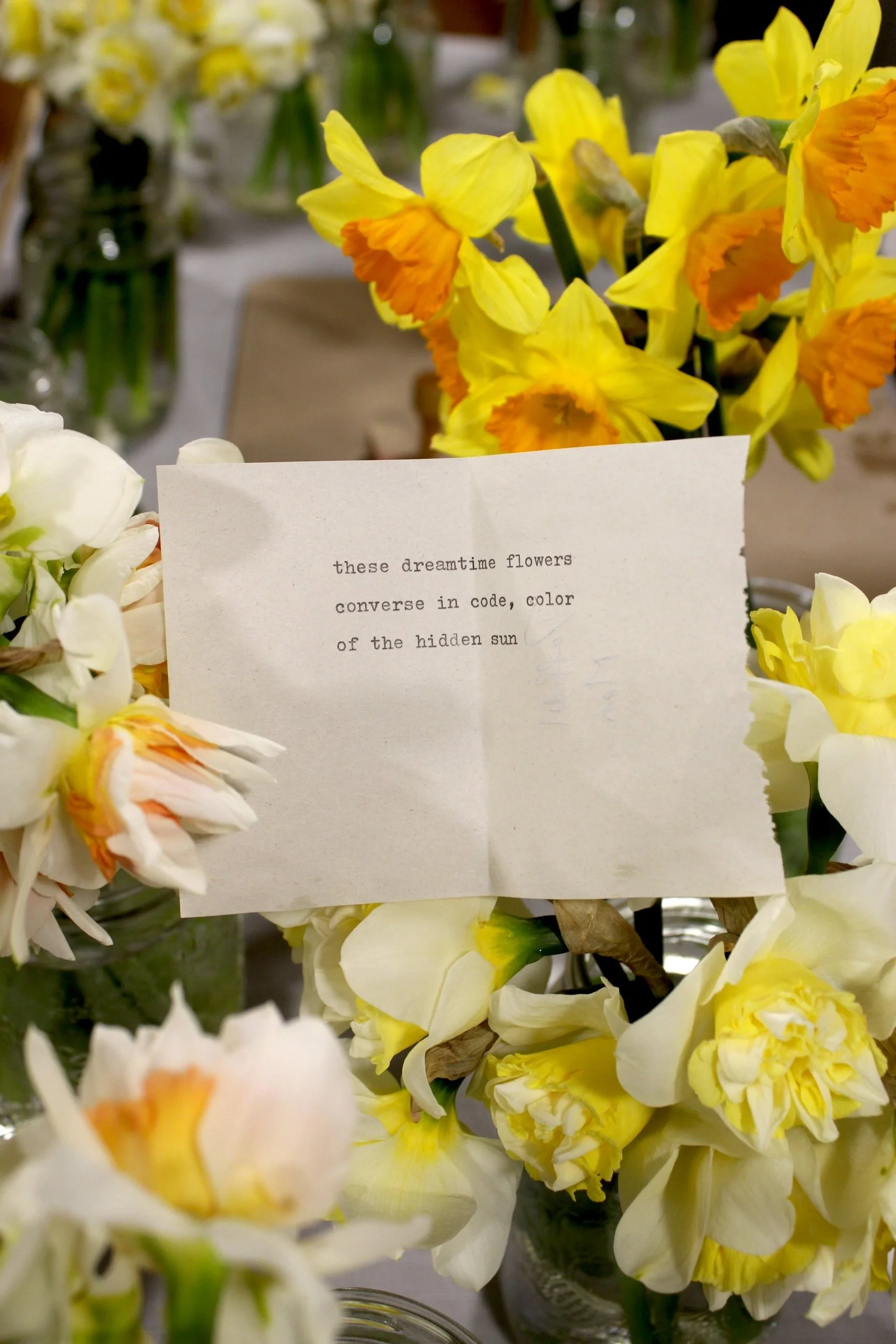

Marc's haiku. Photo credit Lillian Carcao.

Image description: Close-up of a haiku typed on a slip of paper among yellow and white daffodils.

After months of writing poems for people, something happens to the poetic eye. Poetry is inherently reflective, channeling the world through the self. In what I’m doing, the very transactional act of ‘selling’ the idea of a custom poem to someone, then realizing it through the gleanings of a brief conversation, sharpens the senses almost spiritually. You learn to read a person, observe how they dress and interact. You listen between their words for what they are really feeling. The poem amplifies a fragment of the subject’s inner world, connects their desire to express with my longing to listen at the level of the unsaid, the premonition, the latent.

Danielle wants a poem about the moon—which is in a gibbous state—and about skating. She is here with her two sons to skate at the rink.

Gibbous

Skating under the moon

as it waxes a little larger

with every round we make

on its mirrored surface, powder

smooth, a shiny planet of our own.

We are explorers, suited with sticks,

pushing a puck of knowledge, testing

the ice, testing ourselves, how we

slide and stop, race and rest;

how we move against each other

and together in the night while

the moon watches, swelling with pride.

*

In winter, when the market moves indoors to the clubhouse, not as many people come by. Maybe they don’t know that the market carries on throughout the winter months, one of the very few markets in Toronto that stays open all year round. There’s no space in the main hall for me, but Nicole, ever accommodating, asks if I would consider the corridor where a set of entrance/exit doors and the washrooms are located. So I take two chairs and a small bench and set up my stand. It’s warm here—there’s an electric fire blazing away just behind—and it’s also where the kids and adults who are going out to skate change their shoes and take a break.

Some days, parents mill about and eavesdrop on my conversations with people who want a poem. Sometimes, the fathers make offhanded requests.

“My friend asks if you can write a dirty limerick?”

“Sure. What’s your name, sir?”

“Yeah, like can you just freestyle one off the cuff?”

“Uh, I need a bit of time. Limericks have a rhyme scheme and all. I don’t recite poetry, I write it.”

They put on their skates and wander off. This dancing monkey refuses to dance.

There once was a dog from Toronto

Who lived fast and loose in his condo

He strung along his bitches

’Til he burned all his bridges

Lick ‘em and leave ‘em was his motto

*

It is lonely between poems. People who stop to admire the typewriter spout, “Such a lovely idea!” and give me an awkward fist bump. But then they head right on by. They did not account for buying a poem on their weekly grocery run. To them, poetry is passing birdsong, something that so many have left behind in distant classrooms. I call my booth ‘The Poetry Dispensary’ but find myself needing to explain it anyway. People expect poetry to live in a rarefied reading room, to be read or performed at an appropriate tenor for an appropriate audience. Poetry does not exist in the corridor of a community building, nor at a farmers’ market; it should not be invented and delivered in minutes.

Other people offer me life advice once they receive their poems. Maybe they are surprised by how the poem turned out. Maybe they were expecting something along the lines of a fortune cookie. When I tell them I’ve published a number of poetry books in Singapore and that I’ve been writing for 20 years, they start offering me suggestions: places I can teach, run workshops, write poetry, other markets for me to write poems at. But Dufferin Grove remains the only place I ply my trade. I feel a sense of loyalty to the vendors and to Nicole, because she gave me my very first break in Toronto. However, I did take up a suggestion to write poetry on demand at a street festival in July and will be part of the sensuous and mysterious Poetry Brothel Toronto in 2026.

*

It’s a quiet afternoon at the market and Felix sits closer and tells me about himself, detailing his experience of having fought in Bosnia (later amended to two wars).

“I was a pro fighter from 17 to 25, then for the next five years I didn’t really do anything.”

His friend, Raymond, comes by and offers him a can of Lakers beer and a swig from a bottle of Crown Royal Rye. Felix accepts both with a smile.

“For the next… ’97 to 2012, about 15 years, I taught people to fight, then my youngest brother died and… I nearly died too. The next seven years, I was of no use to anyone.”

Here, I interrupt him to write for a vendor at the market who wants a poem for his friend on her birthday. When I am done, Felix heads out for a smoke. He asks me to look after his belongings, among which is a large wok. I don’t ask if he’s living in the park’s encampment. He asks me what I’m writing in between poems and I say it’s a parody song for a performance about losing faith. He shakes his head.

“Such a shame. When you’ve seen what I’ve seen, you would know God is real.”

“Well, I totally respect your views,” I say, “but I just want to say that what you know or call god is known by another name in another culture. Language constrains us.”

“I disagree. Do you know what’s the meaning of hell? It’s a trash heap.”

“Hell is a concept, built on other older religions and apocryphal texts. The whole idea of ultimate good and evil actually comes from the dualism found in the Persian religion of Zoroastrianism.”

“Well, I’ve met God and I’m no liar.” He pauses. “Ok, brother,” he addresses a man who’s sat on the other side of the bench. “What’s your name?”

“Bruno.”

“Bruno, please say, Marc is a concept.”

Bruno says it and apologizes immediately, having quickly figured out that I am Marc.

“He told me to say it,” he says, worried he’d offended me. Then he adds, “But I don’t think you’re a concept!”

“So,” Felix pontificates. “Just as you are not a concept, God, too, is as real as you are. And I met him, just like I met you, a few weeks after my brother died.”

“I don’t doubt your experience,” I say. “Your truth is yours. But it isn’t universal.”

I can see that my words affect him but at this point I get another customer, and he has to break away. Roula wants a poem about moving forward and enacting a shift in her life.

Moving Up

Think of stairs as an ascent

to a different room of thought;

light burnishes differently, the

person you thought you knew

reveals a different facet by these

slats of sunshine that paint new

pictures and warm the floor.

And the house knows better,

it will hold space for you; keep

your days a little lighter against

a burning world that forgets

the rebellion in your name.

Meanwhile, Felix has engaged two security guards in conversation. They are both of Indian origin and are employed by the city to patrol the clubhouse and the park.

“How do you say hello in your language?”

“Namaste.”

“How do you say welcome?”

“Svaagat.”

Felix tries to imitate it, the ‘v’ widening to a ‘w’ sound, so that it comes out as ‘swaggered.’

“What language is this?”

“Hindi. It’s our national language but in each state, we use our own dialect.”

Felix grunts and seems to lose interest right away. He’s clearly buying time while I finish my poem. When I’m done, Felix turns back to me. “I’m not a good man. I’ve been in wars. Done things you don’t wanna know about.”

“I’m sure you have.”

“But you know, you can’t just deny Jesus. I saw him, man.”

“Sure, that’s your belief. And I respect you for that. But it’s no longer mine.”

“How can you write poetry and not believe in God? Isn’t poetry about the wonders of the world that God created?”

“Poetry is about a lot of things. People come and ask me to write poems about relationships, friends who have passed, big changes in life.”

He gives me a deep, searching look. “Listen, can I pray for you?”

“Thank you, but I’m ok.”

He looks very hurt. I think about how many times people have said that line to me or I have said it in return, believing that faith, in all its power and sincerity, would be able to alleviate the situation.

“Are you sure?”

“Yup.”

“When I leave, I’ll turn the corner and I’ll start praying for you, man. You can’t stop me.”

“I won’t stop you! You do whatever you want to do.”

He sighs. “You’re just like Ryan.”

“How so?”

“You’re both lost.”

Marc at Dufferin Grove Market clubhouse 2 . Photo credit Lillian Carcao.

Image description: On the left is a colorful hand-drawn sign, “Poetry Dispensary with Marc,” and the drawing of a typwriter; on the right the author, wearing a cap, leans out from behind the sign to wave and greet the camera.

I’ve not seen Felix since. And I never found out who Ryan was. If Felix was living in a tent in the Dufferin Grove Park encampment, I hope he’s found accommodation somewhere warm. And while he was earnest in his expression of belief, it wasn’t something I had asked for. Rather, he assumed that it was something I needed. I find parallels in how I write these poems. Writing customized poems is like the practice of faith, trusting that there is a way to speak, not to the crowd, but to individual lives. The poems are far from perfect: the metaphors unpolished, the line breaks rough. Sometimes letters get punched wrongly, sometimes there’s an extra spacing. But each of them lives, honestly and with trust, for its intended recipient.

My last poem that day is for Ashok. He’s in the hospital with lung disease. His daughter tells me that he’s a light to people, a family man, a pillar to his community. He loves playing the dhol, an Indian drum. He’s a jeweler.

Precious

Ruby-rich, you have drawn from light

so that you shine when others hold

you up to their hearts, reflecting

your smile against the steady rhythm

of the dhol drum that you beat,

alone and with others, keeping time

like the fine movements of shaping

stones to their setting, honing

selves into significance;

understanding best when a life

is polished and becomes a thing

of beauty; giving and constant.

Marc Nair is a Singaporean poet, photographer, and educator whose practice revolves around developing multidisciplinary approaches to writing and performance. He has published 12 volumes of poetry and works collaboratively with dancers, musicians, photographers, and visual artists. His latest poetry collection is Undulations (2025, Delere Press). He is also working on a solo autoethnographic performance and an exhibition that traces identity and belonging across Singapore, Canada, and India. Marc is currently based in Toronto, Canada.

‘It was early January, and the snow had come down that day like an epiphany.’ – an essay by Max J. Nam.