Editor’s Note: Of the Sea

By Sharmini Aphrodite

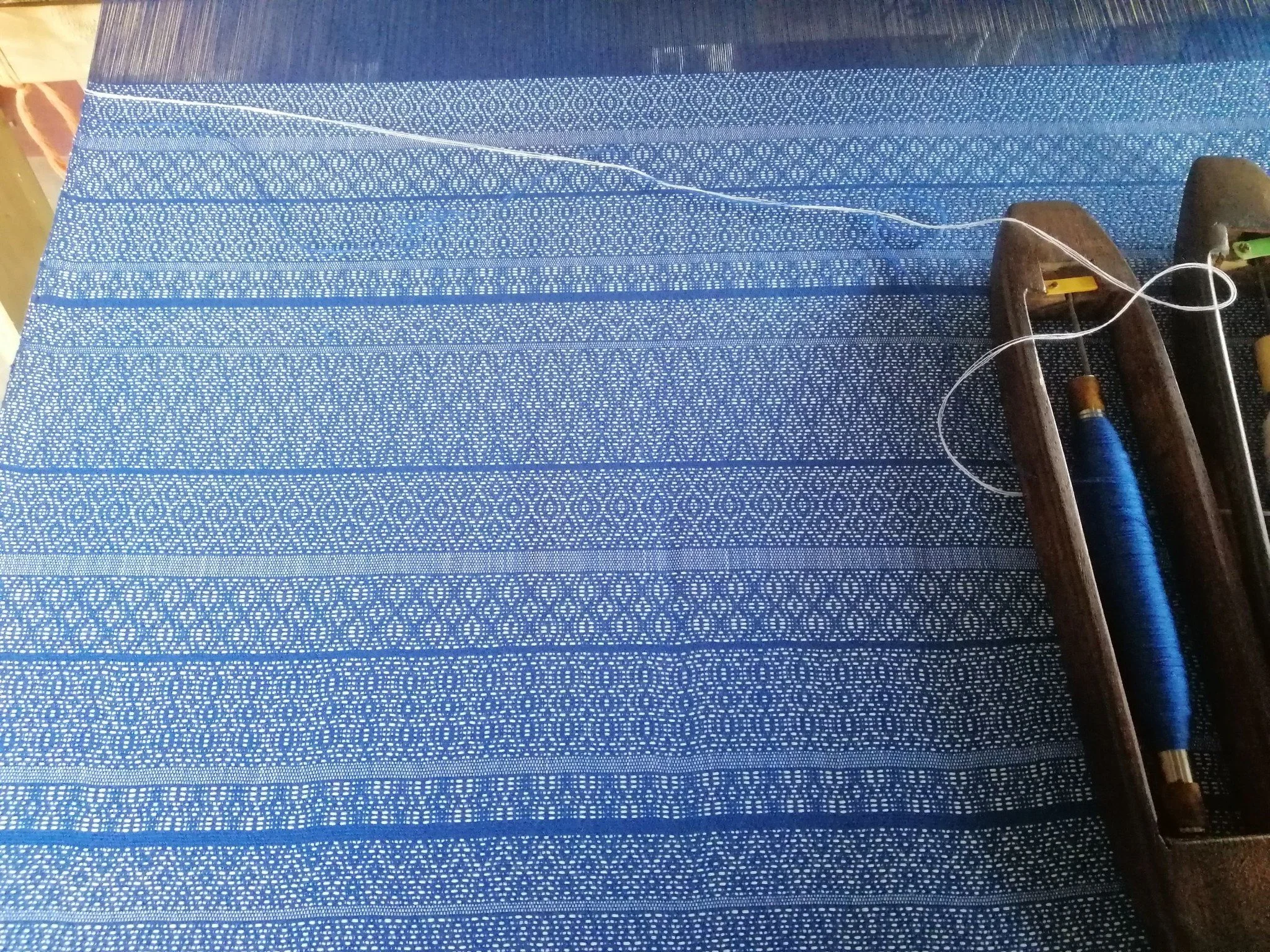

This traditional weaving was made by the Ivatan artists of Simsiman Handwoven Crafts (Catherine de Mata, Jocelyn Cadid, Rowena Mahinay, Lanie Escobido and Kane Gecha) of Batanes. Photograph courtesy of Dorian Merina, July 21, 2025, Naidi Hills workshop.

Image description: The photo shows a piece of textile work. The weaving is blue and white, and features rows of intricate, geometric patterns. On the right side of the image are two weaving tools. Fine, white-colored threads connect the piece of textile to the weaving tools.

The sea takes, the sea gives away. These are familiar words, resonant with those of us who live in a part of the world sculpted by its waves. When we opened our latest submission call, we envisioned it to encompass works from indigenous communities from the region designated as maritime Southeast Asia, aware that borders of nation and region are contemporary contrivances. Land marked out and claimed by the arrival of European ships, desiccated by American wars whether hot or ‘cold’. Cartography running a knife through the region, lines on a map prising apart a shared language and history, storytelling and song. But things are never so simple. The sea frustrates the simplicity of empire.

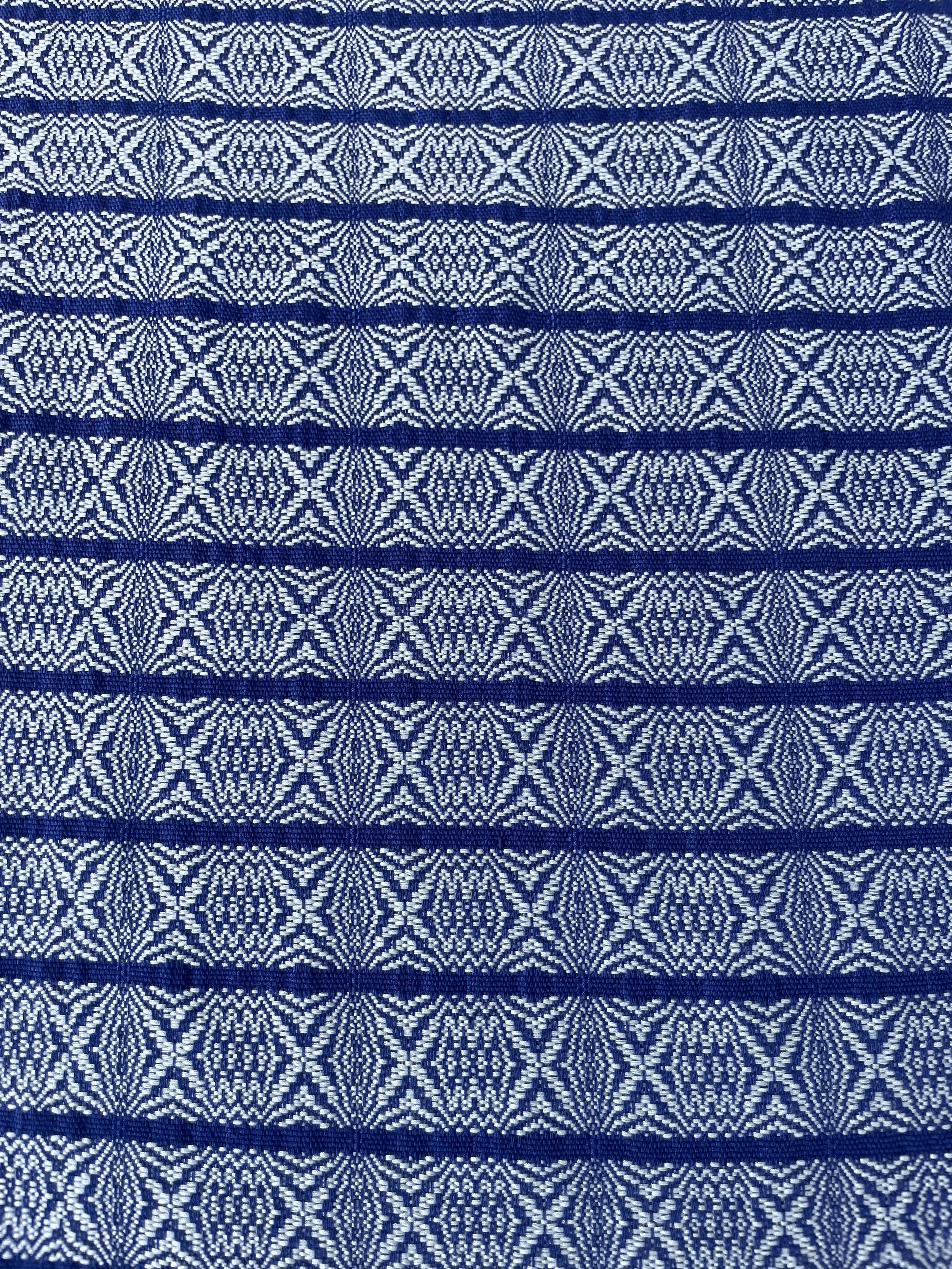

This traditional weaving was made by the Ivatan artists of Simsiman Handwoven Crafts (Catherine de Mata, Jocelyn Cadid, Rowena Mahinay, Lanie Escobido and Kane Gecha) of Batanes. Photograph courtesy of Dorian Merina, July 21, 2025, Naidi Hills workshop.

Image description:The photo shows a piece of blue-colored textile that features intricate, symmetrical, woven patterns that are repeated in rows.

The six pieces in our ‘Of the Sea’ portfolio highlight both the cultural and geographic reach of the tide—as its waves touch Borneo, the Philippines, and Singapore—yet a similar rhythm grounds each one. In ‘Art, Music and Statelessness in Sabah’, writer Erel dialogues with Drop, a Bajau Laut artist, whose work details the violence of border maintenance yet provides ripples of resistance. A set of poems by Napoleon Arcilla evokes the sea in all her majesty and fury, describing the ways maritime communities in the Catanduanes thread their lives with the moods of the waters, clutching rosary beads and stocking rice as the sea swells and skies turn frantic with electricity. In ‘Duyung’ by Sofia Mariah Ma, the urban swirl of present-day Singapore is interrupted by the memories of a matriarch, which resurrect a time when the land respected the sea’s sanctity, memories that also act as a compass towards an ever-changing future.

‘Three Poems from the Celebes Sea’ by M. J. Cagumbay Tumamac were translated from Filipino for our portfolio by Eric Gerard H. Nebran. These poems display the violence of imposing borders onto the ocean—as seen in the fate of a fisherman searching for squid—but also the futility of this project, embodied in the way rain blurs the horizon between sea and sky. In ‘Of Salt and Silver’, Ismim Putera takes us to Sarawak, where the sea and its spirits are not to be trifled with—what they give, they take away.

This traditional weaving was made by the Ivatan artists of Simsiman Handwoven Crafts (Catherine de Mata, Jocelyn Cadid, Rowena Mahinay, Lanie Escobido and Kane Gecha) of Batanes. Photograph courtesy of Dorian Merina, July 21, 2025, Naidi Hills workshop.

Image description:The photo shows two weaving tools. The tools are made of wood. Each tool holds a spool of thread in its center. The tools are placed on a piece of gray-colored textile featuring intricate woven patterns.

The portfolio closes with a collection of Laji—sung oral poetry of the Ivatan people from the Batanes islands in the northern Philippines—compiled and translated for us by Dorian Merina. Merina engaged with the elders of his community for these Laji, which echo with themes of homecoming and return. The photographs accompanying this editor’s note are also of an artform traditional to the Ivatan people, a type of weaving which is currently being revitalised. The pieces on display here shimmer from blue to grey to evoke the ocean and are worn with beads in times of celebration. Each strand possesses generations’ worth of storytelling, of love and labour, and keep affinity with the water, whose tides, no matter how they ebb and flow, remain omnipresent—reminding us that the sea is with us always, and that to the sea we will return.

Sharmini Aphrodite was born in Kota Kinabalu, Sabah, and grew up in Johor Bahru. Her short stories and writing on literature, art, and history have appeared online and in print. She is the editor-in-chief of SUSPECT, a journal of Asian literature and art. She holds an MA in History from Nanyang Technological University and is currently pursuing a joint PhD in Southeast Asian studies (National University of Singapore) and History (King’s College London). Her current academic project focuses on indigeneity, state-making, and more in twentieth-century Sabah, while her research interests include anticolonial movements, agricultural histories, orality, and the history of revolutionary Christianity in the Global South. Her short story collection The Unrepentant is forthcoming with Gaudy Boy in November 2025.

“[Doubt] contains within it a seed of desire, for one can only want what one does not immediately possess.” SUSPECT editor-in-chief Sharmini Aphrodite reviews Jonathan Chan’s bright sorrow.