Poetry in the Age of AI

By Gwee Li Sui

From Eric Valles

This is the transcript of Gwee Li Sui’s keynote lecture at the opening of Poetry Festival Singapore 2025, delivered at The Pod in the National Library on 25 July 2025.

ChatGPT, Gemini, Claude, Grok, DeepSeek. These are words that did not mean a thing to many of us a few years ago. We were all frenziedly in the thick of – if you remember – the COVID-19 pandemic. Did we realise that we were never going to return from that to the same world we went in from? In this sense, we may describe the current explosion of AI use as a new era or even a new pandemic, another existential catastrophe we have to learn eventually to live with.

This afternoon’s topic was proposed to me by Poetry Festival director Eric Valles, who had wanted me to speak with consequence. So let me talk about AI and poetry by way of two related urgencies. The first is to wrap our heads around some key aspects of present AI architecture and to get these right – at least more right than popular impressions do. The second is to address a simple question: how do we as poets live with AI? How do we write in a time so enthusiastically heralded as the end of writing?

No doubt, the question of creation will have crossed your mind as it has the minds of creatives across the whole gamut of the arts. The only people for whom it is neither personal nor interesting are those whose whole medium of work is already AI. These individuals prompt with little need for talent or skill to write, draw, or compose. Their singular expertise lies in crafting instructions.

Let us call them “engineers”, “technicians”, “supervisors”, or even “prompters” – not “creatives”. Near-absent in what they do are the small, invisible, inarticulate, continuous decisions made when a pen or a brush inks or when a note is struck or when a typed sequence appears as it is onscreen. Graphic artists probably know this distinction best as they know that their commissioners – with their many instructions, suggestions, and contestations – are not the artists; they are. Their commissioners are prompters.

The rest of us who hover between whole use and no use, who dabble in AI out of casual curiosity or use it in mediated, self-conscious, or referential ways, are along a spectrum of grey. My first provocation for us today is this: not so much WWJD (ie. “What would Juvenal do?”) as at what point in your writing are you, to yourself, a poet?

Early AI

My earliest encounter with AI went way back to the early 1980s, when my father bought me my first home computer. I was naturally thrilled by now-classic pixelated games such as Pac-Man, Tetris, and Castle Wolfenstein – and then I found the bundled ELIZA clones. Launched in 1966, ELIZA had been the world’s first chatbot. It was rather boldly designed, in view of its limited capacity, to be a split-second, electronic couch doctor.

A typical conversation would go like this:

ELIZA: Hello, I am ELIZA. I'll be your therapist today.

Me: I feel shitty right now.

ELIZA: Do you often feel shitty?

Me: No.

ELIZA: Are you saying NO just to be negative?

Me: No.

ELIZA: Do you expect a different answer just by repeating yourself?

You can imagine just how many patients ELIZA had been successful at curing. It was nonetheless able to keep this teenager occupied for hours, pretending to be conversing meaningfully with an actual someone somewhere across our mutual black screens. ELIZA might have even been an alien – who could tell? This thrilling uncanniness was what I was reminded of when, in a movie many years later, a computer programmer named Mr Anderson read on his screen: “Wake up, Neo... The Matrix has you...”

ELIZA predated all that, especially the online chats where we now do talk with real humans. The programme had simulated real-time conversations – but of the kind whose workings a thirteen-year-old could figure out with ease. Fifteen minutes in, and I knew how it was the keywords in my input that got ELIZA to push out specific pre-formed text. All it needed was enough matchable data to send a human talking in endless loops, granted that he or she was willing to ignore how some lines were repeating.

Today’s chatbots are a far cry from ELIZA, but they are still comparable on two points: they function by pattern-matching, and they rely wholly on pre-inputted data. The difference is that patterns are now recognised at a level of high-dimensional vector representations of words and their clusters. Every piece of information you enter, including a punctuation mark, gets turned into a complex coordinate that branches into multiple associations, entering maps that locate not just meanings but nuances and ambiguities too.

Also, the amount of information AI can process today is staggeringly greater. There are three contributing factors: the incredible processing speed of current technology, the vast scale of that processing, and the frightening amount of energy all this is guzzling. Moreover, data itself is multiplying with more and faster internet use and greater digitalisation. Just consider the sum of data produced every day through messaging, emailing, uploading, etc. when once we would talk more face to face and scribble more on paper.

Alien Intelligence

All these factors go into making today’s AI models look magically or eerily like they can think as we do. But understand: they look so only because all the material they swim in, all that data, are our words, human words, in clusters of information relating to other clusters of human words. AI itself makes nothing.

Imagine a row of books stood and lined as far as your eyes can see. Imagine a short prompt sent through the first book to look for instances where varied combinations of its word-parts can be found. Then it passes through the second book, the third book, the fourth book, etc.; by the time it exits from the other end, there will be thousands of contexts to understand how all the parts cohere. By next comparing these patterns, the best probable word in an answer can be pulled out one at a time and strung – until an answer is complete.

Of course, predictive language modelling is far more complex than that, and my example serves as an absurd conceptualiser. All I wish to make as a point is that AI does not basically reason the way humans reason. None of us think from word to word, nor do we rely on probability to eliminate pre-existing contexts of information to form an answer. There is in us something hazier – call it consciousness – where we reflect, feel, remember, speculate, and destroy even as we pull words in to bring all that into the world.

This is why, unlike (most) humans, AI can spout lies and talk gibberish simply because enough people do so; it has no intrinsic capacity to do otherwise. Did not something similar happen lately when Grok spat out horrific antisemitic responses – no doubt largely due to unfiltered talk on social media and forums? AI can be trained away from such unpleasantries, but then we need to further trust an undisclosed cabal of human puppet-masters to direct its outcome.

In short, we should not think that the first word in AI, “artificial”, is all that sets it apart from humans. Its second word, “intelligence”, is also radically non-human. Even as some chatbots now purport to show us how they are reasoning, debates have arisen over whether that itself is more mimicry: ie. it is not the real thought behind an answer but yet another layer of text.

The Poetry of Poets

Let me then round up this stage of reflection with a second provocation: not only do AI and humans not think alike, but AI merely appears to think because humans think. AI is like that freshman who takes a handful of his or her seniors’ essays and jiggles them into a coherent-looking essay without an ounce of personal thought. Yet, anyone who did not encounter all those other essays could not have known any better!

Such a student’s difference from the good student who does his or her work is at the core of what must matter to a creative. In fact, if you simply ask ChatGPT and others about their intelligence, you will see how they are quite able to describe their reliance on linguistic patterns and probabilistic selections and their absolute limits. Because AI has no physical body, it just has no experience to form beliefs, feelings, and memories to challenge and fundamentally redefine its training.

AI does not, for example, understand what we humans call truths. Its truths are statistically dominant constructs with no invested link to or interest in the outside world. It also does not understand pleasure and pain, those bodily layers that can provide counterpoints to all that is merely informational in the head. But both these two sources of externality and physicality – together with language – are what inheres the human experience.

We have now arrived at the key to the necessary continuing work of poetry – because, in the realm of truth-speaking, poets rule. We do not rule because we are the best at amplifying truths or delineating and emotionalising them. Prose writers, dramatists, artists, songwriters, and film-makers often do that better and with far greater effectiveness.

But – more than other creatives and hauntingly like AI – poets operate in pure language. There is no plot or character that can save us from a bad poem. There is no research on history and place or ragbag of ideological trigger words that can, in itself, make our writing better. Poets use words at their newest and at their least familiar if only to show that even here can be found, counterintuitively, the human experience.

AI Poetry

How does AI write poetry? It writes as it writes prose, but a prompt to write a poem sends it first on a different track. It goes, in other words, into the poetry section of its training library. There it draws on all it has gathered from countless millions of scraped poems – from the Epic of Gilgamesh to today’s Instagram poetry – to replicate forms, styles, themes, and devices.

If AI can thus write a good sonnet, it is because it is weaving with an immense dataset of already inputted sonnets. If AI can conjure a beautiful metaphor, it is because centuries of poets have inscribed the associative potential of each part of that metaphor into being. If AI can write like a particular poet, it is because enough of that poet’s verse exists digitally for it to make choices the poet would make or has already made.

So there is nothing flattering or encouraging about AI mimicking you well, my fellow poets! All this is not to say that AI poetry cannot move or inspire human readers. It technically can – but, when it does, to hail it as having created a human experience inclines towards what we call in literary studies a pathetic fallacy. This is a mistake of reading human emotions and qualities into inanimate things. It is a poetic whim very much like calling a rock stubborn or the sky jubilant; it is not scientific.

Yet here we all are, in a time when many are waxing poetic about AI’s ability to do a poet’s job. What is called poetry here is sewn together from words whose poetic origin lies beyond what a single person has read or can read to call AI out as a student with a stack of his or her seniors’ essays. Originality in AI is limited to the permuted paths of trained associative meanings of words and their clusters not taken before. But, where an association is absent, where there is, between meanings, literally nothing, AI creates nothing.

That void space, that potential in language not just unexplored but fundamentally unlinguistic, is the poet’s gold mine. We are always the ones making it part of language. Did not Percy Bysshe Shelley, in “The Defence of Poetry” (1821), say that “poets are the unacknowledged legislators of the world”? In his “Letter on ‘Humanism” (1949), Martin Heidegger famously writes:

Language is the house of being. In its home, human beings dwell. Those who think and those who create with words are the guardians of this home.

AI may use language and be made with language, but it does not live in it. To live somewhere, you have to be paradoxically distinct from its material; only then can a dwelling be more than a structure as a home to be cherished. So here is a third provocation: poets, celebrate your corporeality. if your poetry is disembodied, without self-knowledge or an intimate project with words, AI can do you. If there is no pre-linguistic mind forcing its way into language to disrupt language, AI can do you.

The Way Forward

It feels odd that, by taking the war into language, technology has somewhat sharpened the focus on language as the ancestral home of poets. What should then be our practical way forward in response? Allow me to draw my lecture to a close by offering some concrete steps, whether they be for passionate action or composed non-action.

To begin with the latter, you can do nothing. You can keep writing as if it matters ultimately how you know that you are writing. This response emanates from a relationship with purity and an ascetic disregard for the shifting sands of the real world. That the self writes and struggles through writing brings artistic purpose quite independent of whether AI can spew out the same poems successfully.

Or you can kick back by locating the spaces that AI has not reached or cannot reach and writing there. The most obvious space among these is the latest in current affairs and fields of knowledge. You can essentially beat AI at the time game since its training data is normally months behind, with its gaps in real-world awareness being plugged by trending news. What this means is that AI’s responses here tend to read less digested.

You can differently look inwards and manifest the human more in two basic ways. One way is to hound yourself into highly subjective perspectives, convictions, and memories – because such impassioned centredness, wilfully blinkered and self-delimiting, is what AI is not designed to become. The other way is to draw on a core of profound human encounters and queries, at which language itself has yet to arrive.

Then there is the confident remaking of language, and here we are grappling with experimental transformations of word use. We seek to make language speak, look, feel, and perform in ways it has not, contorting it with illogic and subversion and essentially defamiliarising it. Only poets understand how humans have this ability to find meaning beyond the familiar and even in strangeness, contradictions, non sequiturs, and nonsense and to experience all that as fresh, powerful, and even life-affirming.

On what more can be pursued, I have no more to say in specific. But let me make my central point crystal clear: poetry is not dying. It has hardly begun to be shaken. This is rather the time for poetry to re-till the ground and, in the field of communication, reveal how we and all speakers have barely known language. Language is not shaped by usage; this is where AI gets it crucially wrong. It is shaped by what has not been spoken and remains to be made flesh.

From Nilanjana Sengupta

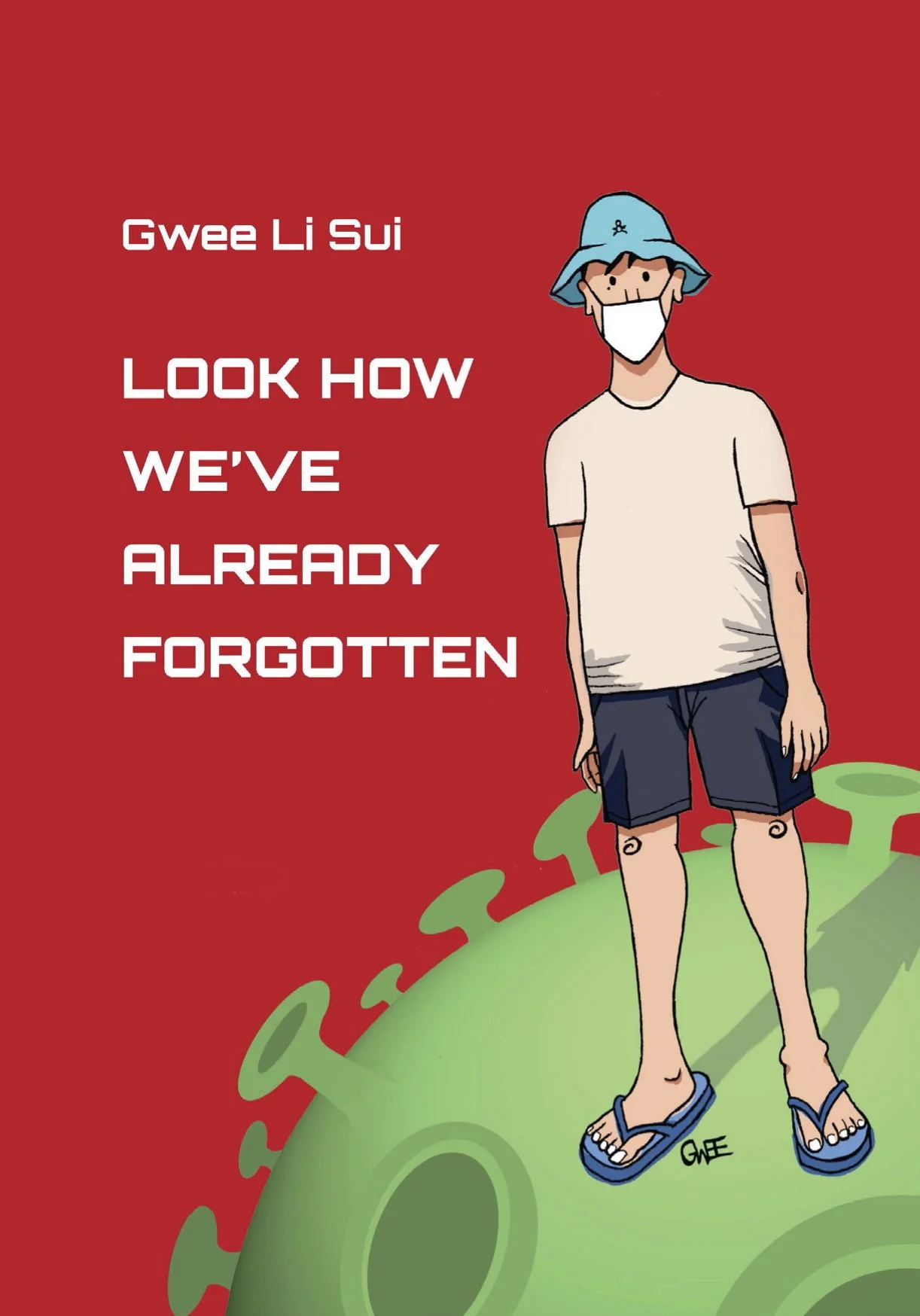

Gwee Li Sui has recently released his eighth collection of verse, Look How We’ve Already Forgotten. He also draws and translates, his latest translation being Kaka Farm, which renders George Orwell’s Animal Farm into Singlish and features his illustrations.

‘Style, tone, and form aren’t just decoration—they’re the architecture of meaning... A plastic chalice cannot hold sacred wine.’ – an essay on meaning-making by Chadawan Yuddhara.