Translation as Weapon

By Elise J. Choi

Review of Babel, or The Necessity of Violence by R. F. Kuang (USA: Harper Voyager, 2022)

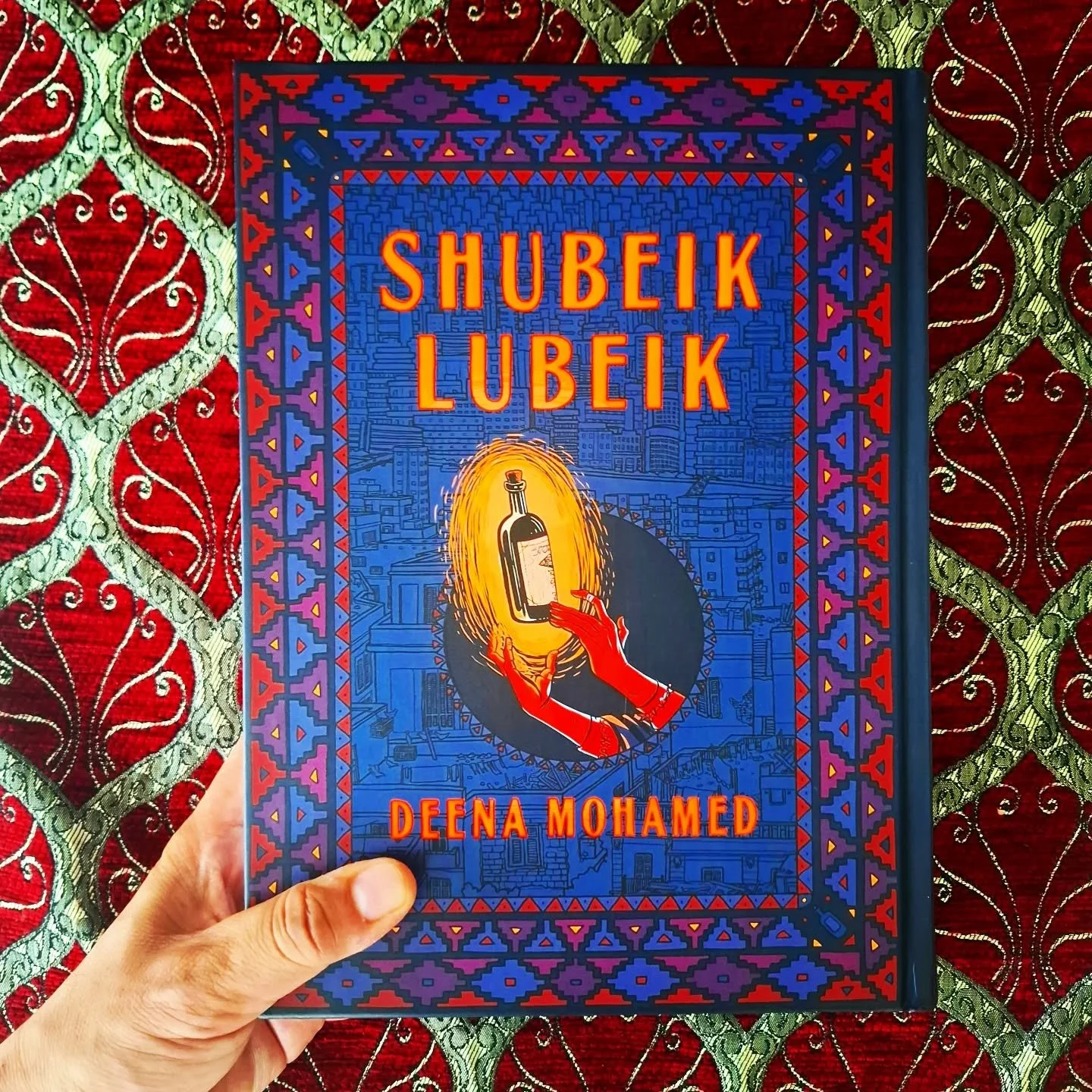

US book cover of Review of Babel, or The Necessity of Violence by R. F. Kuang (USA: Harper Voyager, 2022)

How to take on British imperialism and the history of translation (and its weaponization) in a single novel? That’s R. F. Kuang’s mission in her latest, with the appropriately lengthy title of Babel, or The Necessity of Violence: An Arcane History of the Oxford Translators’ Revolution. Though not always succeeding, Kuang seeks, on the scale of a magnum opus, to reclaim a part of Oxford history almost always attributed to white men and to imagine a rebellion by students of color within the ivory tower. In a departure from her epic fantasy trilogy The Poppy War, Kuang here creates an alternate history of the 1830s with just a flourish of fantasy.

Robin Swift (whose Chinese name we never learn; “I have a name, it’s—” “No, that won’t do.”) is orphaned as a child by cholera in his hometown of Canton, China, and swept away to London by a cold white man. We learn soon that this is Robin’s absentee father, Richard Lovell, an Oxford professor who specializes in Mandarin and is the secret sender of the English-language books that Robin devours every month. Lovell assigns tutors, enforces a strict regimen for Robin to become versed in Latin, Greek, and Mandarin, and is abusive if Robin strays from his studies. After coming of age, Robin is taken to Oxford, where—though encountering frequent racism—he finds a new family in his cohort and a new home in the translation studies department, called Babel.

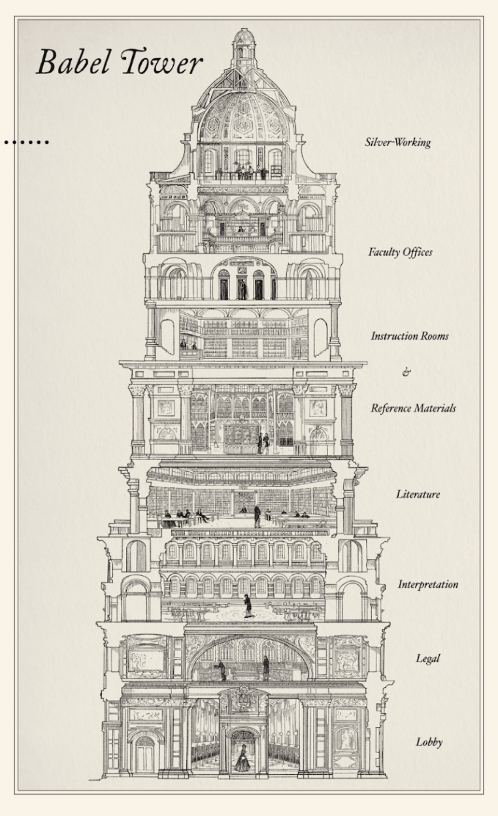

A map of Babel Tower, the (fictional) translation department of Oxford University.

Though fictional, Babel symbolizes the allure of Oxford as “a tower out of time, a vision from a dream. Those stained-glass windows, that high, imposing dome….” The eighth and highest floor is dedicated to silver-working, the sole fantastical element of the novel’s universe that drives the plot. Silver bars, powered by translation inscriptions, cure illnesses, make rooms bigger, carts and ships faster, explosions more deadly. Robin’s utopia is cut short, however, when he’s visited by Griffin, a member of the mysterious Hermes Society, who removes the rose-colored glasses, explaining that the silver manufactured by Babel’s faculty and students is what powers the British empire, which is about to stoke a full-scale opium war against China. Initially doubtful, Robin is eventually converted and joins in the effort to topple Babel, and therefore the empire.

Babel leans into the academic fiction genre, from its lithographic cover art to the chapter epigraphs by historical figures and the many footnotes (fictional and nonfictional). It’s at its most enchanting when delving into the theories and praxis of translation via Robin’s courses at university; the reader gets to listen in on the lectures, which must have derived from Kuang’s own academic background and countless trips down Oxford English Dictionary rabbit holes. Many of the seminars are focused on fundamental concepts that all translators should study, such as fidelity to the source text versus the target text. In an introductory lecture, a professor lays out the crucial problem that translators have always faced:

“Translators are always being accused of faithlessness…. Fidelity to whom? The text? The audience? The author? …. Is faithful translation impossible, then? But what is the opposite of fidelity? Betrayal. Translation means doing violence upon the original, means warping and distorting it for foreign, unintended eyes. So then where does that leave us? How can we conclude, except by acknowledging that an act of translation is then necessarily always an act of betrayal?”

Translation as betrayal leaves the realm of academia as Kuang explores how translation in the West has historically empowered European nations to exploit their colonies; it is never merely a scholastic exercise, as the university feigns. Such real-life issues are clarified through the metaphor of silver bars, whose magic relies on the fundamental idea of untranslatability—there is never a one-to-one equivalent. Speaking aloud the words inscribed on the silver bars and invoking the historical and linguistic tensions are what produce magical results. For example, the tension between invisible and wúxíng—formless, incorporeal—renders the spell chanter unnoticeable. Creating such match pairs is the work of fourth years, who study etymology: “We can think of etymology as an exercise in tracing how far a word has strayed from its roots…. When we invoke words in silver, we call to mind that changing history.” As an illustration, a professor proffers the Greco-Latin “Typhon,” a monster with a hundred heads; which became the Arabic ṭūfān to denote violent winds; which traveled to the Portuguese tufão; which was carried over on ships to the Chinese táifēng; and went on to the English typhoon. Some readers may find these daisy-chain etymologies dull, but others will appreciate the nerdery.

Kuang does the work to represent characters of color in a traditionally white genre. Robin’s experience as a half-Chinese, half-white person in nineteenth-century England is a perspective I haven’t seen before. Much of the time, however, the tone defaults to preachy. Robin’s cohort includes Ramy from Calcutta, Victoire from Haiti, and Letitia, or Letty, from France. Ramy and Victoire are faultless and come across as poster Gen Zers who know the handbook of racism inside and out. Conversely, Letty’s role appears to be Annoying White Woman for most of the book, as when she responds to Ramy’s critique of the British occupation of India: “It’s not as if you have had it all so bad… If you think that, then what are you doing in England?” One wonders why the others put up with her, except for the fact that she later enacts a major plot point. The three characters of color become friends instantly and display a perfect friendship throughout. When Robin commits a crime that could earn him the death penalty, Ramy and Victoire immediately jump to help cover the crime with no thoughts of their own culpability. On the one hand, it’s a comforting vision of solidarity placed in direct contrast to the racism they face from Letty and all other university sectors; on the other, I wish there were a little more nuanced complexity, perhaps in the form of interminority racism or academic rivalry. It’s an example of how the book lives in frequent binaries: us against them, POC versus white people, Britain against China (never a mention of China as an empire).

Kuang goes out to destroy Oxford in her novel, but she’s also clear about her love for the institution. It’s a tricky balance, one that may confuse the reader every now and then. The early pages of adoration describing Oxford as, finally, a home for Robin, are never quite suppressed in the latter half of the book when the characters realize their school is what enables the British Empire to engage in warfare overseas. The magnetism of Oxford is inextricably bound up with its prestige and the subsequent snobbery that can emerge. For instance: “‘You don’t even speak French.’ ‘It’s French, Letty.’ Ramy rolled his eyes. ‘Latin’s flimsiest daughter. How hard could it be?’” Such a throwaway line is meant to be humorous, but it can make the reader feel like an outsider looking in rather than feeling immersed in the world.

The slow-burn revolution culminates in a high-stakes standoff that’s been building up for five hundred pages, and the book illustrates well how academia—often viewed as a passive, low-stakes endeavor—can change the world. By this point, Robin has grown from student to activist, taking the learning meant to turn him into a puppet of empire to create an uprising instead. The novel also reminds us that revolutions are messy, fraught always with intragroup conflict. Whether the revolution succeeds is left unwritten, but perhaps that’s a moot point here—Robin is determined to carry on the movement regardless of its outcome.

Babel is an ambitious project that succeeds in its explorations of translation theory but falls short with its two-dimensional character development and didactic depictions of racism. Nonetheless, it fills a gap in the dark academia bookshelf and does important work reclaiming history. In the end, it’s a sincere love letter to language and reading, and that in itself makes it worthwhile to pick up.

Elise J. Choi (she/her) is a Korean American copy editor based in Portland, Oregon, and reads science fiction, fantasy, and translated literature to her cat. She has a master’s in English from the University of Oregon and has been a writer, translator, instructor, and doodler.

If you’ve enjoyed reading this article, please consider making a donation. Your donation goes towards paying our contributors and a modest stipend to our editors. Singapore Unbound is powered by volunteers, and we depend on individual supporters. To maintain our independence, we do not seek or accept direct funding from any government.

In Taiwan Travelogue, ‘twinned souls… are at once lost, but also found, in translation.’ A review by Eunice Lim.