Fog of January

TRANSLATORS’ STATEMENT

In early January 2022, Central Asia was rocked by the bloody aftermath of unexpected protests in Kazakhstan. Those protests started out peacefully, but soon turned chaotic, with official announcements that unspecified "terrorists" had invaded the country in an attempt to topple the government, and orders were issued to shoot to kill. Soldiers imported from Russia appeared in the streets. Protesters dispersed quickly in half a dozen cities, but in Almaty, the cultural capital, the chaos grew worse. Over the course of several foggy January days, the time usually dedicated to celebrating the New Year devolved into a nightmare. Innocent people of all ethnicities, young and old, were shot where they stood or were arrested and disappeared. More than a month later, no list of the dead and injured and arrested has yet been made available, and nobody is even sure how many are dead or missing.

Translators Shelley Fairweather-Vega and Katherine E. Young spent three weeks assembling and translating seven poems by half a dozen Kazakhstani poets who reflect on this trauma and uncertainty in the immediate aftermath of events. Most of these poems appeared in the online literary journal Literratura in February 2022, while others first appeared on Facebook. Our selections were driven purely by how these poems resonated with us personally. Given unlimited time and emotional capacity, we would have translated even more. While all these poems were originally written in the Russian language, each is suffused with a decidedly Kazakhstani mentality. Together, they are a plea for understanding, for answers, for a better future for their country and their compatriots.

We should note that as we worked on these translations, Russian troops were massing on the border of Ukraine, another country trying hard to determine its own fate. While still processing their own trauma, our Kazakhstani friends have also been speaking out boldly against Russian aggression in Ukraine – including by public protests! – despite the fact that the Kazakh government officially professes neutrality. Their principled stand and personal bravery are examples for us all.

Dariya Temirkhan - Quarantine Series 1 (2020)

Image description: Mixed-media collage of orange and purple hues. Some of the images have stretched and distorted textures, with the main focus being the cut-out images of three topless men bending forwards, sightly outlined in white.

ТУМАННЫЙ ЯНВАРЬ / Oral Arukenova

Translated by Shelley Fairweather-Vega

***

мама говорила

нет ничего прекраснее слова

ужаснее слова

папа говорил

нет ничего важнее истины

страшнее истины

внутренняя волчица шепчет

нет ничего сильнее крови

беззащитнее крова

я говорю себе не бойся

это всего лишь слова –

истина дом кровь

туманный январь

в сером небе ни звезд ни луны

лишь отблески взрывов

на стеклах высотки

весь мир растворился

в дыме и хаосе.

прикрываясь туманом

из верхних престижных

стекались к центру

бородатые рослые

призраки прошлого –

ассасины

из нижних районов

шли толпы разгневанных

оседлать

нефте-долларового быка

выхлестнуть ярость

на гламурные символы

хозяев жизни и слуг народа.

жители города яблок

не сразу поняли разницу

между хлопками петард

и стрельбой автомата

из окон домов

несмелыми струйками

сквозь грохот и гарь

пробивались молитвы

утренние вечерние

многократные

пятничные

субботние

воскресные.

клубами расползалась паника

не отвеченных сообщений

звонков

возбужденные возгласы

уф вы живы

что там у вас происходит

по новостям сказали

что стреляют по мирным жителям

зачем только вы обратились к путину.

в сером небе ни звезд ни луны

лишь отблески взрывов

на стеклах высотки

весь мир растворился

в дыме и хаосе.

между западом и востоком

между западом и востоком

твоё да – моё нет.

аруаки

спасите меня от пустых слов

оставляющих жалкий след

да обойдет меня сеть интриг

из чужих обид.

пусть нет будет нет

без моего суда

без верхнего суда

суда потустороннего

с чувством вины

где любой шаг –

преступление за

которым следует смерть

физическая или духовная.

люди и запахи излучают:

да – каждый второй

в патологии

с явным признаком цвета кожи

нет – мир состоит

из бесцветных хамелеонов.

да обойдет меня стороной

твоё да твоё нет

родина враг сосед.

*Аруаки – (с каз. языка) духи предков.

Fog of January

I.

mama used to tell me

there’s nothing more beautiful than a word

more terrible than a word

papa used to tell me

there’s nothing more vital than the truth

more frightful than the truth

the she-wolf inside me whispers

there’s nothing more powerful than your den

more helpless than your den

I tell myself have no fear

this is nothing but words —

the truth home blood

II. fog of january

no stars no moon in the lackluster sky

just the glint of explosions

in high rise windows

the whole world decomposed

in chaos and smoke.

concealed in the fog

of the high and prestigious

they dripped to the center

husky and bearded

ghosts from the past:

assassins

from the lowlier places

came the angered crowds

to mount and ride

the petroleum-dollar bull

to splash their fury

on glamorous symbols

of life’s own masters and civil servants.

the apple city’s people

could not immediately tell

the firecrackers’ bangs

from machine gun fire

from apartment windows

in hesitant trickles

through thunder and char

the prayers broke through

for morning for evening

many times over

for friday

for saturday

for sunday.

gusting the panic crept spreading

from messages unanswered

and calls

exalted exclamations

oh you’re alive

what’s happening where you are

they said on TV

that they’re shooting civilians

why would you ever go to putin.

no stars no moon in the lackluster sky

just the glint of explosions

in high rise windows

the whole world decomposed

in chaos and smoke.

III. between west and east

between west and east

your yes is my no.

aruaqtar

shelter me from empty words

leaving a pitiful trace

may the web of intrigue and

foreign grievances pass me by.

let no be no

without my judgment

without higher judgment

judgment otherworldly

with a sense of guilt

where any step

is a crime that

is followed by death

physical or spiritual.

people and odors both radiate:

yes – fully half of us

are pathological

with pronounced signs of skin color

no – the world consists

of colorless chameleons.

may it pass me by

your yes and your no

motherland neighbor foe.

*Aruaqtar (Kazakh) are the spirits of the ancestors.

Oral Arukenova is a poet, literary critic, and translator. She studied the German language in Almaty and business management in Hamburg. Her stories, poems, and articles have been published in literary journals in Kazakhstan, Russia, Germany, and the United States, including in Brooklyn Rail and the forthcoming anthology Amanat.

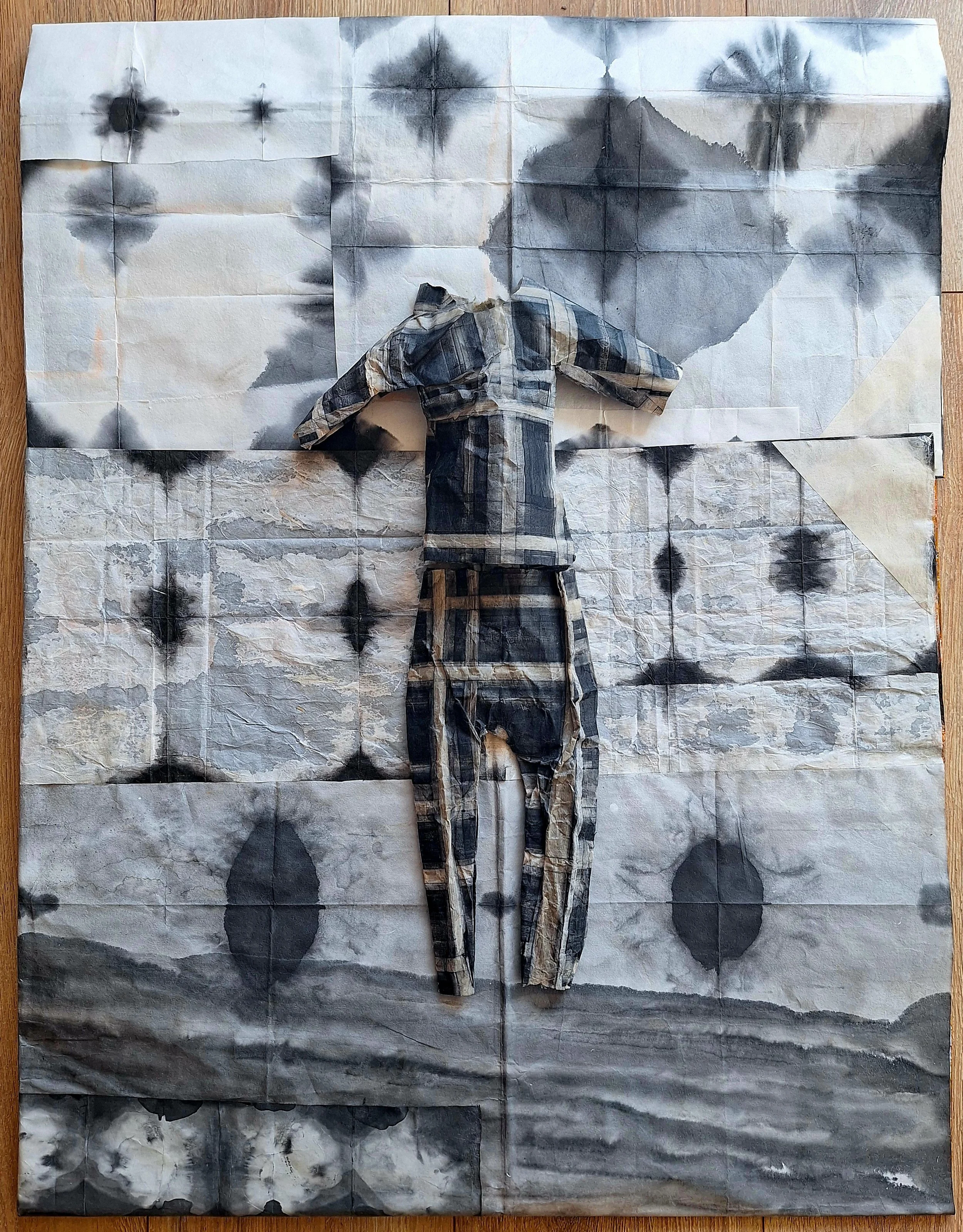

Dariya Temirkhan - Quarantine Series 2 (2020)

Image description: A reddish, mixed-media collage with cut-outs of images and pieces of writing. Three smiling faces of women, resembling deities, are scattered throughout the artwork.

Анастасия Белоусова / Anastasiya Belousova

Translated by Katherine E. Young

житель окраин

окуклилась

скопила

надышала тепло

братья и сестры мои по кокону

глаза их прояснились

руки освободились для объятий

время отпустить сандалии упархивать в балконные края

время читать стихи а не новости

слушать мысли а не ютуб

время в расплавленной карамели

янтаря

вязко и жарко

а потом "по три раза ходят на опознание: алматинцы не хотят верить в смерть"

протянулась пуповина

ледяной иглой всеклась в заворот пупка

10.01.2022, Алматы

[Untitled] “an inhabitant of the outskirts”

an inhabitant of the outskirts

pupated

gathered and

breathed in warmth

my cocooning brothers and sisters

their eyes lit up

arms broke free for hugs

time to let go of sandals take flight for balcony realms

time to read poems and not the news

to follow thoughts and not YouTube

time in the melted caramel

of amber

gooey and hot

and then “they go three times to identify the body: Almaty’s people don’t want to believe in death”

umbilical cord stretched out

icy needle jabbing the belly button’s whorl

10 January 2022, Almaty

Anastasiya Belousova was born in Almaty in 1996. She has a master’s degree in specialized literary studies and is a graduate of the program for poetry, prose, and children’s literature at the Open Literature School of Almaty.

Асел Омар / Asel Omar

Translated by Shelley Fairweather-Vega

НЕ СТРЕЛЯЙ

Спроси мое имя, пока я здесь.

Не плачь, мое сердце еще стучит,

Моя плоть превращается в глину.

На могиле моей вырастут маки,

Я верю.

На площади, уже видевшей кровь,

я не знаю, кто мне друг, и кто мне враг.

Я всего-то хотел справедливости.

Всего-то. Но ведь справедливости нет?

Спроси мое имя, пока жива моя мать.

Я поднял руки вверх,

Не вижу лиц тех, кто смотрит на меня в прицел.

Не вижу шевронов –

Слишком густой туман в январе,

И небо бело от вспышек гранат.

Ты же видишь, я безоружен.

Вожди называют нас великим народом

с телеэкранов,

Я стою здесь, подняв руки,

И мне все равно, как они нас назовут.

Ты просто не стреляй.

Не стреляй в меня.

Спроси мое имя, когда маки расцветут на моей могиле,

Когда тело мое станет частью земли.

Спроси мое имя, пока я здесь,

Слишком густ белый туман вокруг,

Это не автоматная очередь, не шумовая граната,

это сердце мое стучит

в последний раз.

Мама, это все еще я, прости.

Не плачь, просто сегодня слишком густой туман,

Слишком белое небо,

В которое я улетаю.

Don’t Shoot

Ask my name while I am here.

Don’t cry. My heart is still beating,

My flesh is turning to clay.

Poppies will grow on my grave,

I have faith.

On the square, which has seen blood before,

I don’t know who’s a friend, who’s a foe.

All I wanted was justice.

Only that. But maybe there is no justice?

Ask my name while my mother is alive.

I put my hands up,

I can’t see the faces of the ones who have me in their sights.

I can’t see their chevrons –

The January fog is much too thick,

And the sky’s gone white from exploding grenades.

You can see, though: I’m unarmed.

The chieftains call us a great people

from the television screens,

I’m standing here, my hands up,

And I don’t care what they call us.

Just please don’t shoot.

Don’t shoot me.

Ask my name when the poppies flower on my grave,

When my body becomes a part of the earth.

Ask my name while I am here,

The white fog is too thick around me,

That’s not machine gun fire, not a stun grenade,

that’s my heart beating

for the last time.

Mama, it’s still me. I’m sorry.

Don’t cry, it’s just that the fog is too thick today,

Too white, the sky

I am flying away into.

Asel Omar is a graduate of the Maxim Gorky Literature Institute in Moscow and a member of the Writers’ Union of Kazakhstan. She is the author of four books of fiction, a collection of poetry, and numerous articles. Her long short story “Black Snow of December,” about a popular political uprising in Almaty in 1986, caused great controversy at the time of its publication.

Dariya Temirkhan - From Fragments (2020)

Image description: Mixed-media collage, dark blue with hints of yellow. The collage consists of fragments of artwork, such as the background elements of a Gustav Klimt piece and the figure of a woman with pale blue skin. In the top right corner there is a cut-out of a woman’s face, and in the lower left corner, we see the nude lower region of a woman’s body.

Канат Омар / Kanat Omar

Translated by Shelley Fairweather-Vega

ЭТО В МЕНЯ СТРЕЛЯЛИ

когда пожилые родители пересидев у дочери все три кошмарных дня

и заставив сидеть с ними сына

который поначалу рвался на площадь чтобы видеть своими глазами

как народ наконец говорит

пусть неумело косноязычно задыхаясь от ярости но честно

и оттого речь его чиста

а потом увидев по центральному телеканалу

(потому что интернет сразу отключили а независимых журналистов

сделали зависимыми от воли случая и пули-дуры)

погромщиков с их криворотыми предводителями

тех самых титушек знакомых по зарубежным новостям прошлого десятилетия

а следом за ними трясущихся от вожделения мародёров

рушащих любимый город

то сразу как-то сник и просидел с ними вместе

все эти три дня

со стариками сестрой и племянниками

так вот когда пересидев три дня у дочери и дождавшись затишья

пожилая пара отвозит сына на стареньком митсубиши до самой его квартиры

чтобы с ним ничего по пути не случилось и затем успокоенная

возвращается наконец домой

её без предупреждения расстреливают военные

прицельным огнём на поражение

очень точным как на стрельбище или экзамене на политическую зрелость

умение стремительно развернуться по ветру

и сохранить невозмутимость

как будто бы это совсем не позорно и несгибаемые предки столетиями

учили именно этому

и автомобиль взрывается и горит на перекрёстке

как во время войны

которую объявили себе

не спросив никого

и никто его не тушит потому что никому нет дела

и сын всё никак не может дозвониться до стариков

и потом они с сестрой ищут по всему городу

звонят в полицию больницы морг

и только на четвёртый день находят останки автомобиля

на том самом перекрёстке

и сын собирает пошатываясь

рассыпающийся пепел любимых

обугленные косточки матери

хрупкий как ёлочная игрушка из новогоднего детства череп отца

и никак не может отскоблить

от металлического остова

драгоценную присохшую грязь

шепчущуюся с ним золу

и тогда ему помогают сделать то что он должен

те кто уже давно мертвы

когда об этой истории

как и многих таких же

– о застреленных детях о сгоревших заживо семьях о пулевых отверстиях в окнах мирных домов –

рассказывает жена

её рука с чашкой дрожит и красный остывший чай едва не выплёскивается на белоснежную

рубашку с короткими рукавами

а почему она в рубашке когда за окном январь

ведь она сидит за кухонным столом у окна и смотрит не отрываясь на улицу

от которой тянет холодом

кто мне ответит

5 февраля 2022

THIS IS THEM SHOOTING AT ME

after his elderly parents have been hunkered down at their daughter’s place three nightmarish days

and they made their son sit with them, too

at first he’d been out on the square to see with his own eyes

how the people were finally speaking up

honestly even if clumsily tongue-tied and gasping with fury

which made their speech pure

but once they’d seen on the government channel

(because the internet was immediately shut down and independent journalists

were made dependent on the will of fate and stray bullets)

the marauders and their wry-mouthed ringleaders

the same titushki they all knew from the international news of this past decade

and behind them looters quivering with lust

destroying the city they loved

Then the son wilted quickly and went to stay with them

all those three days

with the old folks and his sister and nephews

so after they’ve sat at their daughter’s place for three days until it is calmer

the elderly couple drives their son in their old Mitsubishi to his own neighborhood

to make sure nothing happens to him on the way and then feeling relieved

finally set off for home

they are shot without warning by soldiers

targeted fire shooting to kill

with great precision like target practice or a test of political maturity

the skill for quickly twisting in the wind

and maintaining impassivity

as if there were nothing shameful about it and their stalwart ancestors spent centuries

teaching them nothing but this

and the vehicle explodes and burns at the crossroads

like in a time of war

that has declared itself

without asking anyone

and nobody puts it out because it’s nobody’s business

and the son can’t seem to get a call through to the old folks

and then he and his sister search the whole city

they call the police and hospitals and morgue

and it’s only on day four they find the car’s remains

right there at the crossroads

and the son is shaking as he collects

the scattered ashes of his parents

the small and blackened bones of his mother

his father’s skull fragile as a pine-tree bauble from a boyhood holiday

and he just cannot scrape

the priceless baked-on grime

with the ashes stuck in it

from the metal frame

and then they help him do what he must

those who died long ago

when this story

as well as the many like it

– of executed children families burned alive bullet holes in windows of residential buildings –

is told by his wife

the teacup shakes in her hand and the cold red tea almost splashes on her snow-white

short-sleeved blouse

and why is she wearing short sleeves when it’s January out there through the window

she’s sitting at the kitchen table by the window after all her eyes are glued to the street

from where the cold seeps in

who can tell me

February 5, 2022

Kanat Omar graduated with a degree in film direction from the St. Petersburg State Cultural Academy in 1996. He has lived in Astana since 2001. His writing has been featured in journals and anthologies of Russian-language poetry from Kazakhstan and the international Russian-speaking world.

Рамиль Ниязов / Ramil Niyazov

Translated by Katherine E. Young

Колыбельная

I.

аул уехал в даль

словно в волчью ловушку

ты залей слова мамá

в моё пустое ушко

укради меня туда где течёт

Есентай под родимый кров

а не вен фабричный

берёзовый сок

и красная сперма-краска

аткян чаем рассвета ставшая

мы пьём его ночью

и зубы крошатся

а по арыкам

то солёным то сладким

течёт ледяной

пресной кипяток

и до звезды достаёт

бирюза

на вкус что

будто святой была

II.

где Фурманова вспоротое брюхо

почему-то оказалось пусто

саркыт бедным стала пустота

богатым — садака

на весь чёрный свет поминальный плов

в белоснежном казане приготовь

от сглаза занавес алый навесь

в на солнце сгнившее мясо

что называлось бог

чистые бритвы руками грязными

положи под язычок

III.

семью звездами стакан

нефтью огранённый до дна

залей в каспийское море рта

сердце прополоскать

сигарету об грудь затуши

белый буран

попробуй вкусить

—

он почти как «берёзовый сок» —

как то самое

ненужное детство —

вкусный и ненастоящий

—

он почти что

святой

и признает ли мать

одного

из пропавших своих сыновей

по тавру

под отрубленным язычком

Lullaby

I.

the aul moved off into the distance

as if into a wolf trap

pour the words mama

into my empty little ear

steal me away to where

the Esentai flows beneath my beloved home

and not a factory-made vein

birch juice

and red cum-paint

has become salty atkyan the tea of dawn

we drink it at night

and our teeth crumble

and along the irrigation ditches

either salty or sweet

flows icy-

fresh boiling water

and turquoise

reaches for a star

as if it

were holy to the taste

II.

where Furmanov’s split belly

for some reason turned up empty

emptiness became leftovers for the poor

sadaka for the rich

cook a commemorative feast for the whole black world

in a snow-white cauldron

hang a scarlet curtain against the evil eye

in the sun-rotted meat

that was called god

lay clean razors under the tongue

with dirty hands

III.

pour a glass with seven stars

faceted to the bottom with oil

into the Caspian Sea of your mouth

to rinse your heart

put out a cigarette on your chest

a white snowstorm

try to taste it

—

it’s almost like birch juice—

like that

unnecessary childhood—

delicious and unreal

—

it’s almost

holy

and does a mother recognize

one

of her missing sons

by the brand

beneath his severed tongue

Ramil Niyazov-Adyldzhyan is a poet, artist, and translator. He is an alumnus of the Open Literature School of Almaty (poetry seminar by Pavel Bannikov) and an employee of the Krel Cultural Center; he graduated from the department of liberal arts and sciences of St. Petersburg State University. In 2019 he was longlisted for the Arkady Dragomoshchenko Prize. He is the editor of polutona.ru.

Dariya Temirkhan - Untitled (2020)

Image description: A dark-blue, mixed-media collage. On the left is a painting of a hunched and hooded skeleton holding a club. The robe of the skeleton is patterned with circles and crosses. On the top right is a pale image of a woman similar to paintings by Gustav Klimt. The middle portion of the collage shows a distorted gray portal with two dark and stretched figures.

Ирина Гумыркина / Irina Gumyrkina

Translated by Katherine E. Young

***

И страшно так, Господи, страшно –

Уже невозможен побег:

Чернеет на площади башня,

И замертво падает снег.

За краем, за раем, за воем

Не видно, не слышно Тебя.

Нас перекроили без воли –

Узнаешь ли прежних, скорбя?

По буквам читай эсэмэски,

Молчи, как молчит «Телеграм».

Почти невозможно, но если –

Нас всех – отпусти до утра.

[Untitled] “And it’s scary, Lord, it’s scary—”

And it’s scary, Lord, it’s scary—

There’s no more escape to be had:

The tower showing black on the square,

And snow falling as if dead.

Beyond the edge, heaven, the howl,

I can’t see You, I can’t hear.

We’ve been remade against our will—

Will You recognize us, grieving?

Spell out every SMS,

Hush, like Telegram: go dormant.

It’s near impossible, but if

You can: release us all till morning.

Ирина Гумыркина / Irina Gumyrkina

Translated by Katherine E. Young

***

Этот город увековечен

В «Шаныраке» и «Акбулаке»,

В кетлинге и кибербуллинге,

В «Сулпаке» и реновации,

В исчезнувших трамваях,

Исчезающей мозаике,

В сгоревших памятниках

Советской архитектуры.

В январском тумане

Скрывается нечто ещё –

Если найдёшь какую-то связь,

Напиши петицию

В небесную канцелярию,

Чтобы было что рассказать

Следующему поколению.

[Untitled] “This city’s immortalized”

This city’s immortalized

In Shanyrak’s trauma, Akbulak’s,

In kettling by police,

In cyberbullying,

In rebuilds, trees cut down

To “beautify” Sulpak,

In long-vanished tramlines,

In a missing mosaic,

In the burned-out landmarks

Of Soviet architecture.

Something else is hidden

In January’s mist—

If you find any connection,

Offer up a petition

To the chancery of the heavens

So you’ll have something to say

To the coming generation.

Irina Gumyrkina was born in 1987 in eastern Kazakhstan. She completed the poetry seminar at the Open Literature School of Almaty and works as a journalist and editor. Gumyrkina has published her poetry in the journals Plavuchy most, Prostor, Etazhi, Zvezda, and more, and is the author of two books of poetry.

Shelley Fairweather-Vega is a professional translator of Russian and Uzbek in Seattle, Washington. She translates poetry, fiction, screenplays and more for authors around the world, with a special focus on the contemporary literature of Uzbekistan and Kazakhstan. Fairweather-Vega holds degrees in International Relations and Russian, East European, and Central Asian Studies. As a translator, she is most interested in the intersection of culture and politics in modern history. Her published projects and work in progress are at fairvega.com/translation.

Katherine E. Young is the author of the poetry collections Woman Drinking Absinthe and Day of the Border Guards and the editor of Written in Arlington. She is the translator of Look at Him (Anna Starobinets) and Farewell, Aylis (Akram Aylisli). Her translations of contemporary Russian-language poetry have won international awards; she was named a 2017 National Endowment for the Arts translation fellow. From 2016–2018 she served as the inaugural Poet Laureate for Arlington, Virginia. https://katherine-young-poet.com/

*

Temirkhan Dariya was born 2000 in Almaty, Kazakhstan. She grew up in Uralsk and now lives in Almaty. Collages of the young Dariya Temirkhan immerse you in a world of fragments where open memory framing what she saw collects new ideas. The author uses a collage technique by collecting pieces of words and images from magazines and newspapers into her own story. Dariya explores the Kazakh language as a means of creating new archetypes in the young generation, enriching the outcrops with antique plastic.

If you’ve enjoyed reading this article, please consider making a donation. Your donation goes towards paying our contributors and a modest stipend to our editors. Singapore Unbound is powered by volunteers, and we depend on individual supporters. To maintain our independence, we do not seek or accept direct funding from any government.

What consumes us? Three poems by Alison Clara Tan.