Uncle’s house; it was noon

By Jiaqi Kang

After Maxine Hong Kingston and The Strokes

Jiujiu rolls up his sleeve and shows us his pockmarks. They come in four rows and three columns, which I know is twelve without having to count the way Didi is counting, his index finger hovering above those little perfect circles of wrinkled skin. The pocks are like yawning mouths, lips doing a constant work of stretching and shifting. They hiss at the attention, flutter a little, seem to want to retreat, until Jiujiu shushes them and they settle.

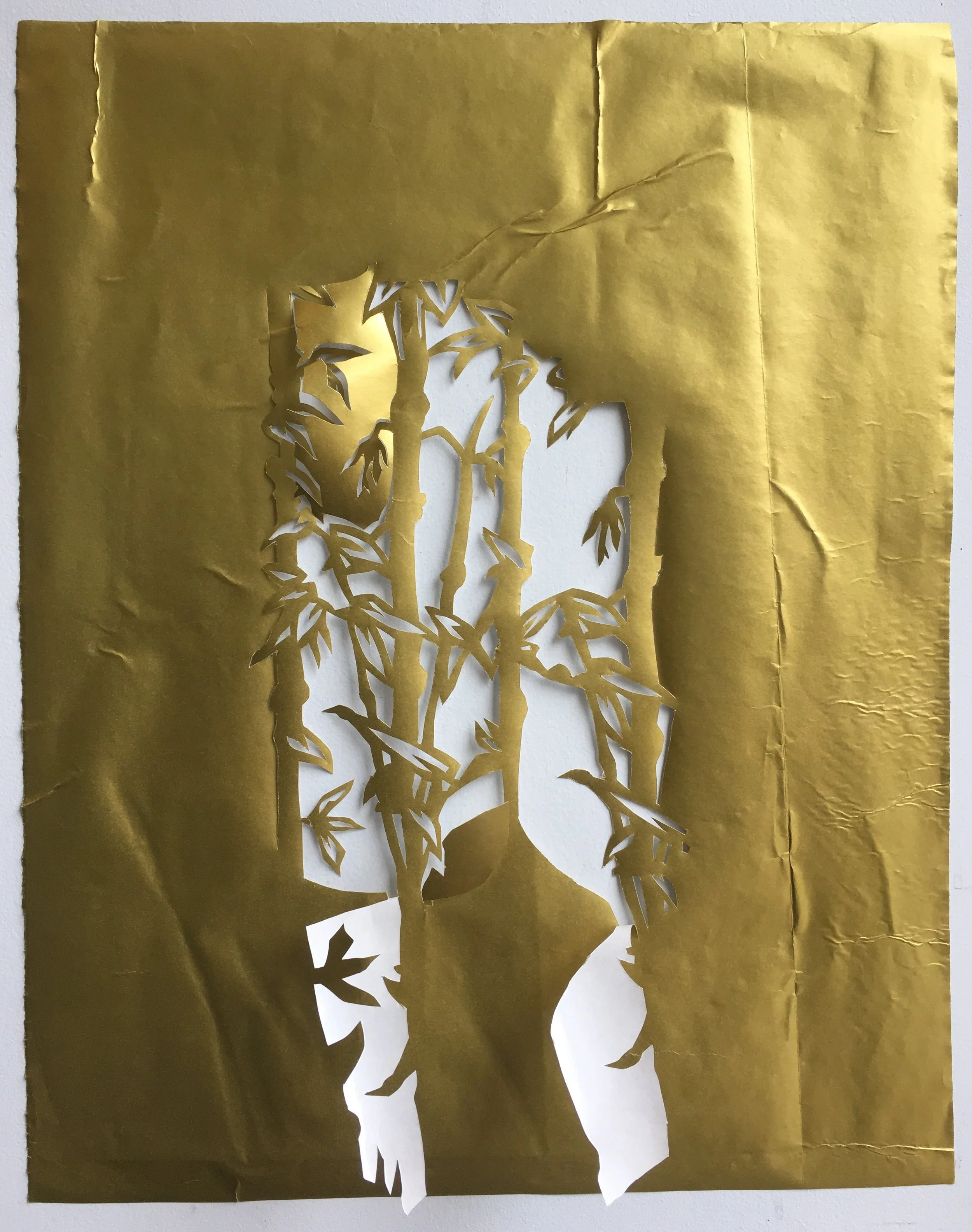

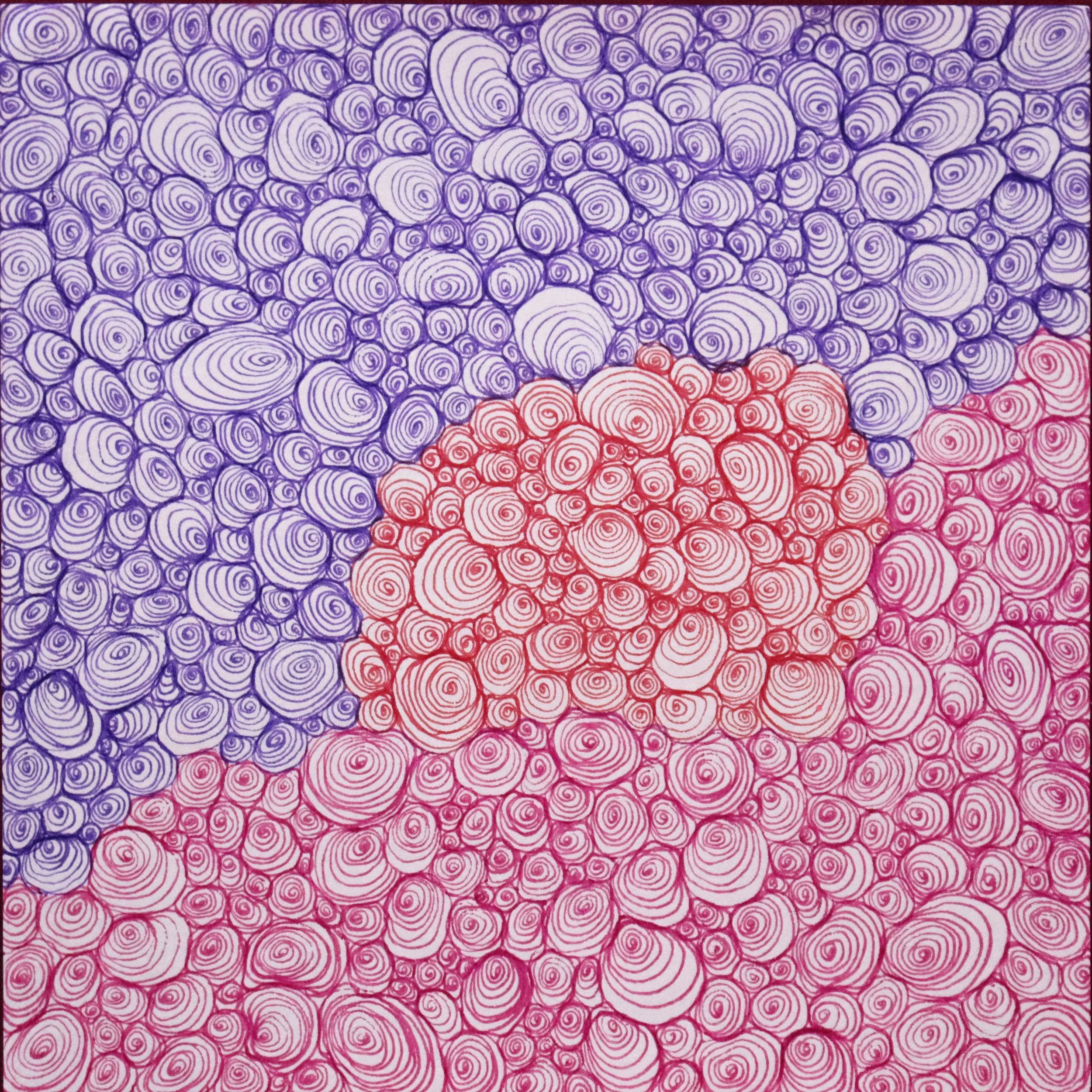

Chao Harn Kae - Greedy, 8x15x14cm, Terracotta, Black Earthenware, Stoneware (2022)

Image description: A clay sculpture of three hands grasping at each other in a triangular formation. The hands are in different colors: reddish-brown, light beige, and dark brown. Each hand’s wrist has a froglike face that is attempting to devour the fingers of the other hands in a cyclical sequence.

With practiced motions, Jiujiu tears open a box of Pandas and starts taking cigarettes out, one by one, placing them into the awaiting mouths, whose pale lips close around the filters and let out soft, almost unintelligible mmmmms of pleasure. Jiujiu is still holding his forearm out so that Didi and I can see, and upright like this, the cigarettes look like sticks of incense. We are so small here; the only incense we’ve seen is when we get taken to eat vegetarian food at Maman’s friend’s temple on new year’s day.

The mouths start puffing and fill the bedroom with smoke, but not even asthmatic Didi dares to cough. Jiujiu tells us that Maman used to get bullied at school for being too smart. She’d never admit, now, that she once allowed such a thing to happen. One day, Jiujiu took a shovel from the courtyard and followed her tormentors home. That’s how he got these scars. Did it hurt? we ask. Does it still? What about this scar, and that? I look at Didi and wonder if he’d ever let me fight for him.

Downstairs, the key turns the lock, and Jiujiu cranks open a window, tosses his forearm onto the ledge. The mouths let their spent cigarette butts fall away as they exhale into the dusk air, lips puckering, taking in, pushing out. Didi runs to greet Maman. I follow, getting up slowly from the desk chair, avoiding the stacks of ash on the floor. I shut the door to the bedroom, the room that Didi had to cede when Jiujiu showed up fresh off a plane two weeks ago. Behind it, there is laughter.

The next day we come down to breakfast and Jiujiu is gone. His seat at the table is piled with ads from the mail. He won’t be back, Maman whispers, ever. She is eating cut-up apple with a fork and sucks at the tines even though she’s always telling us not to do that. After the dishes are washed, we clean out his room and scrub the floors. The ash has accumulated on the bookshelves, except for where there is a still-sealed pack of lights.

Chao Harn Kae - Greedy, 8x15x14cm, Terracotta, Black Earthenware, Stoneware (2022)

Image description: A clay sculpture of three hands grasping at each other in a triangular formation. The hands are in different colors: reddish-brown, light beige, and dark brown. Each hand’s wrist has a froglike face that is attempting to devour the fingers of the other hands in a cyclical sequence.

Later, Didi asks if it’s true Maman was born with eleven fingers. If it’s true there was a muddy pond behind the family compound where you could swim with the frogs, the way Jiujiu liked to do when he was twelve. Maman says no; she says that the year Jiujiu turned twelve there was a drought. She says not to listen to anything he tells us, especially not secrets.

Jiaqi Kang is the founding editor-in-chief of Sine Theta Magazine, an international, print-based publication made by and for the Sino diaspora. They are a doctoral student in art history, researching hygiene politics in postsocialist Chinese art. Their fiction can be found in Hobart, Jellyfish Review, and X-R-A-Y. Find them online: jiaqikang.carrd.co.

If you’ve enjoyed reading this article, please consider making a donation. Your donation goes towards paying our contributors and a modest stipend to our editors. Singapore Unbound is powered by volunteers, and we depend on individual supporters. To maintain our independence, we do not seek or accept direct funding from any government.

‘But later… we didn’t talk about love. We talk about the land and its people.’ – a short story by Kaushik Ranjan Bora, translated from the Assamese by Aruni Kashyap.