#YISHREADS April 2022

By Ng Yi-Sheng / @yishkabob

This is my second column, and I’m afraid I’ve already messed up my own job description! This month, rather than just featuring Southeast Asian books, I’m also highlighting novels from China and India, partly cos I’m personally/geographically connected to their creators (translator Jeremy Tiang is Singaporean and author Sharanya Manivannan used to stay in Malaysia), and partly cos they happen to be brilliant works that I think everyone ought to read.

In fact, my reading list this month skews a lot more towards fiction (no more borrowing access to my university library, y’see) and towards women authors (partly cos I read this lot in March, i.e. Women’s History Month, partly cos of the luck of the draw). My literary consumption is swayed by a lot of factors—in fact, I’d be open to more suggestions on what to read in the comments section. What works from the (greater) region need to be amplified?

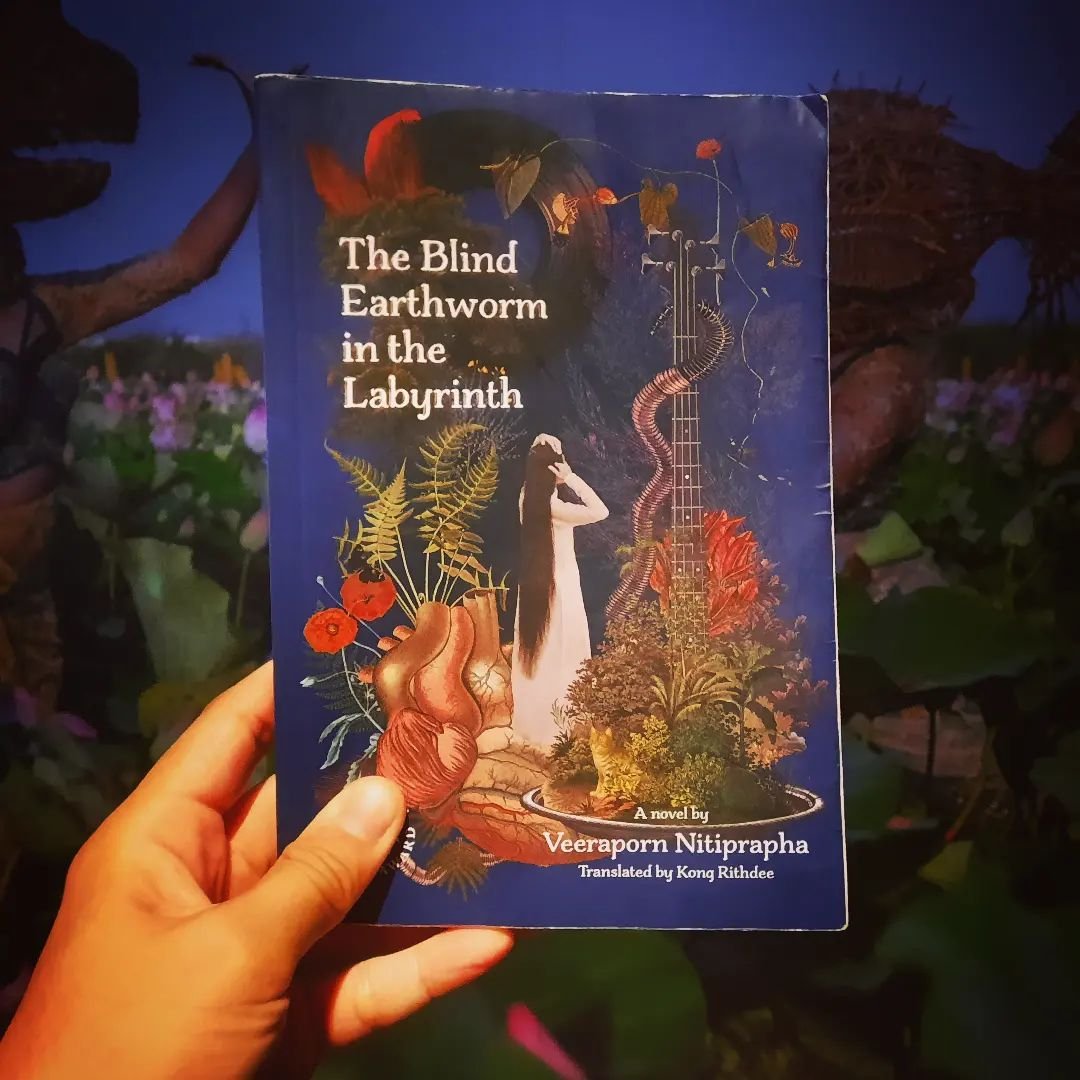

The Blind Earthworm in the Labyrinth, by Veeraporn Nitiprapha

Translated by Kong Rithdee

River Books, 2018

Heavens, what an astounding book. Published in Thai in 2015, this is the author's first novel, and an exemplar of Southeast Asian magical realism & Cixous' écriture féminine.

At its core, it's about two middle-class sisters, Chareeya and Chalika, & a working-class boy named Pran who saves the eldest from drowning in a river; how they grow up profoundly lonely, lost in unrequited longing for one another’s (and various other partners’) love—the back blurb explains that it’s very much informed by the aesthetics of Thai soap operas. But it's not told linearly: we jump back & forward through time, through the eyes of diverse characters: uncles, paramours, parents, friends, each suffering from their own bitternesses and neuroses (except for the cleaning woman Nual, who's emerged from a ghost-cursed childhood to actually be generous w her love, thus raising a thriving polyamorous family w three husbands).

And god, the textures of the garden, flourishing w Mon roses and pikul trees; the old house chock-full of Uncle Thanit's antique textiles from Bhutan and Peru, and vinyls of Beethoven and Schumann; Chareeya's kitchen where she effortlessly prepares Moroccan and Mexican cuisine and Chalika's sweetshop full of diverse Thai delicacies and men going mad over her beauty... the sheer mango-sweet tropical excess of it is plain-heartstopping.

I know I started off recommending Nitiprapha in weirdly academic terms, but I do need to convey the fact that she's breaking loads of conventional rules about how to write a novel—even her magical realism isn't spec-ficky at all, with coffins sinking deeper into the ground and corpses walking almost incidentally, with the connotations of characters' endless cycles of Buddhist rebirths as much symbolic as vividly true, w the richness of the text forcing the eye to read much slower than anticipated. (It's just 200 pages, but it took me over a week to finish.)

Plus I wanna recommend the historical specificity of all this: it's a thoroughly Gen X novel, and the great dramas of the late 20th century from the Thammasat University Massacre to the war in Lebanon to the millennium countdown pulse in the background while the characters drive each other to despair & bliss; as the encroachment of the megalopolis of Bangkok edges closer & closer to swallow up their bucolic paradise of Nakhon Chai Si. As much as I might be exoticising the Thai-ness of this all, I'd also say the intricate mandala that the author spins is one that encompasses the whole world.

Making Kin: Ecofeminist Essays from Singapore, eds. Esther Vincent and Angelia Poon

Ethos Books, 2021

This book's perhaps the first attempt to introduce concepts of ecofeminism to Singapore, with contributions from an extremely diverse set of writers, not just in terms of race, sexual orientation and disability status, but also (and this is pretty rare) age, spanning generations from the 86-year-old veteran feminist Constance Singam to the Yale-NUS undergrad and Speak for Climate co-founder Tim Min Jie.

But does it work as a collection? That's more questionable. Some of the pieces are beautifully written and deeply insightful, e.g. Serina Rahman's account of her life as an environmental educator in a beach village in Johor; Ann Ang's description of her friends' urbanised rejection of her birdwatching knowledge; nor's exploration of their artwork giving dignity to their Malay trans womanhood through the spirit of Bumi/Pertiwi, the earth goddess; Tim's insistence on the need for care for activists rather than driving them to despair and burnout. Some are more personal and poetic, e.g. Diana Rahim's memories of her family's minyak lam, or homemade herbal medicinal oil; Prasanthi Ram's detailing how the forests turned from a site of fear to a place of refuge during the pandemic.

Many essays, however, don't quite fit the theme. Andrea Yew's struggles as a female practitioner of Brazilian jujitsu are a great reflection on body politics, and Tania De Rozario's jaw-dropping story about enduring an exorcism by her fundamentalist mother is a treatise on horror and trauma, but neither speaks directly about environmentalism. Some authors are frustratingly not self-aware: Choo Kah Ying never discusses the neocolonial dynamics that allow her to send her autistic son to live w carers in Bali; Kanwaljit Soin seems unaware of the high ecological cost of her cruise to Antarctica, which inspired her vegetarianism; Grace Chia's quarantine-baking memoir speaks of the conquest of yeast rather than celebrating interspecies symbiosis.

Plus, a couple of pieces are plain hard to read! That's the price of inclusivity, I guess.

Ethos Books seems to be marketing this as a sequel to its earlier essay collection, Eating Chilli Crab in the Anthropocene, which impressed the hell out of me—way more uniform in literary polish & academic rigour, but also a little formulaic, and all drawn from Yale-NUS students. Important for us readers to understand that a project like Making Kin is a different one, almost a demonstration of the internal variety within the category of “SG woman”, and a prompt to consider how different activist causes may be intertwined.

And let's be real: it's great that it's not all New Agey paeans to the beauty and suffering of Mother Nature. Womanhood, feminism, ecology, activism—they're all complicated things, and this book reflects that.

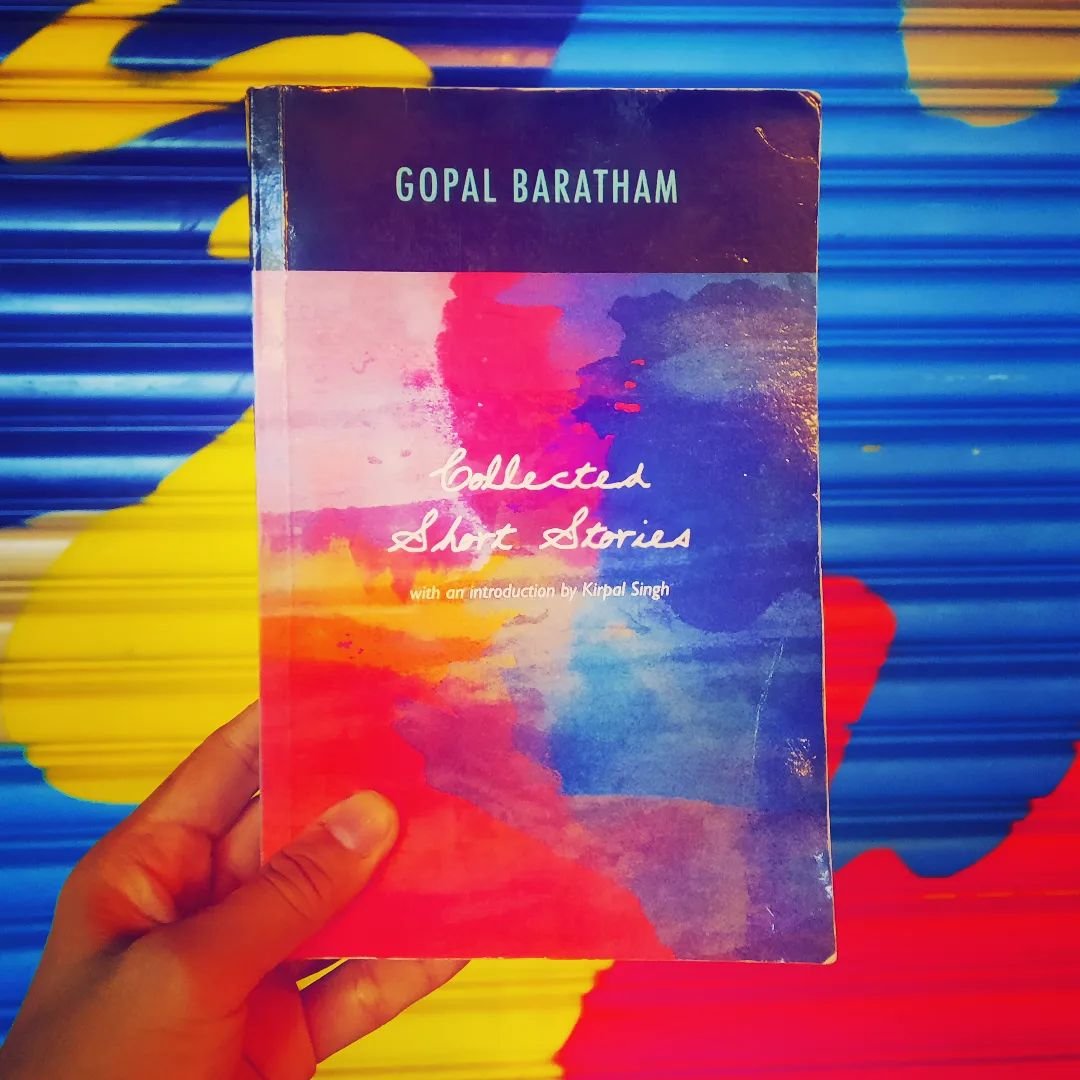

Collected Short Stories, by Gopal Baratham

Marshall Cavendish, 2014

This has been on my reading list for a while, for a number of reasons: the author was one of the leading lights of Singapore Anglophone literature before his death in 2002, and even mentored a few of my contemporaries at the Creative Arts Programme. He’d explored taboo topics like HIV and the 1987 activist crackdown Operation Spectrum in his novels, and I’d heard in his short fiction he’d even ventured into sci-fi. All this on top of balancing a full-time career as a celebrated neurosurgeon!

But TBH, I hadn’t loved the bits and pieces I’d read of him thus far—he came across as this self-satisfied dirty old man, obsessed w sex, but speaking w a voice & sensibility that belonged to a distant, youthless generation. Would my opinion change after reading a full 39 of his stories, taken from Figments of Experience (1982), People Make You Cry (1988), Memories that Glow in the Dark (1995) and The City of Forgetting (2001)?

Well, kinda! I’m still flabbergasted by his nymphomania: his male characters screw around prodigiously and describe lust in graphic detail, recalling the exquisite musk of their mistresses, whores and wives. But then his female characters also frequently exercise their agency (even to a comical degree, as described in “Gretchen’s Choice”, about a young working-class Tamil woman welcoming the sexual revolution in the 70s by playing two white lovers against each other).

Virtually all of the loving is interracial, mostly between Chinese, Indians & Eurasians (you’d think from these tales that SG was 50% Eurasian, when in fact it’s more like 0.4%), and with no gendered power dynamics therein (plenty of Chinese men schtupping white and Indian women). & to recall that he was doing this in the 80s and 90s, a time of considerable social conservatism—well, that’s just baller.

Plus, his sex isn’t just an exercise in toxic masculinity (though some icky bro-hood is on display in tales like “Korean Agate”). There’s something primal about it, less like the loneliness of queer longing than simple bodily hunger that must be satisfied, sometimes directed at bodies that wouldn’t be on advertising billboards (dark skin, the ageing body, the pungent body). Plus he’s going into it w all these religious allegories from Hinduism and Christianity that aren’t fundamentalist at all, but expansive. It’s an attitude to sex from a different era, and I think we’ve something to learn from it.

Ah, but let’s talk about generations. Born in 1935, Baratham was first published only in 1974 (the story was “Island”, a tale of a middle-aged Englishman and an 18-year-old Caribbean girl). So he came into the literary world not as a fresh kid but as an already older voice, with pre-war and pre-independence memories to share. These he explores in startling tales of the British colonial and Japanese Occupation eras, as well as startlingly sympathetic stories set during the Communist Emergency: my favourite, “Tomorrow’s Brother”, actually features a Malay MCP soldier who carries out a mission to capture and execute his horrible capitalist brother, and in doing so finds comradeship w his Chinese fellow soldier (that I personally headcanon not just as a bromance, but a romance).

Having lived through all these regimes, Baratham’s also able to excoriate the PAP rule w some authority in works like “The Personal History of an Island”, where he unabashedly proclaims that “the new freedom was worse than the old bondage”; or “Main-main”, where a passionate childhood romance with an Indian coolie girl turns out to be fruitless to renew in adulthood, cos she’s all middle-class and made-up and has forgotten even the titular Malay euphemism for sex that she taught the narrator. (There’s even a piece against CPF, the government’s social security scheme, “Providence”, which I’d assumed only became controversial in the 2010s!)

So yeah, Baratham’s work is worth reading still, though you might want to use a historicist rather than a fundamentalist SJW lens while you’re at it. No need to be too merciful, mind you: the appended interview with Ban Kah Choon from 2000 has him labelling “the unintelligible rubbish that we see especially in poetry and the theatre.” Also, the introduction by Kirpal Singh is hair-raising. Are we really expected to love the author on finding out how much he wept after killing a girl during brain surgery, because she was so sexy???

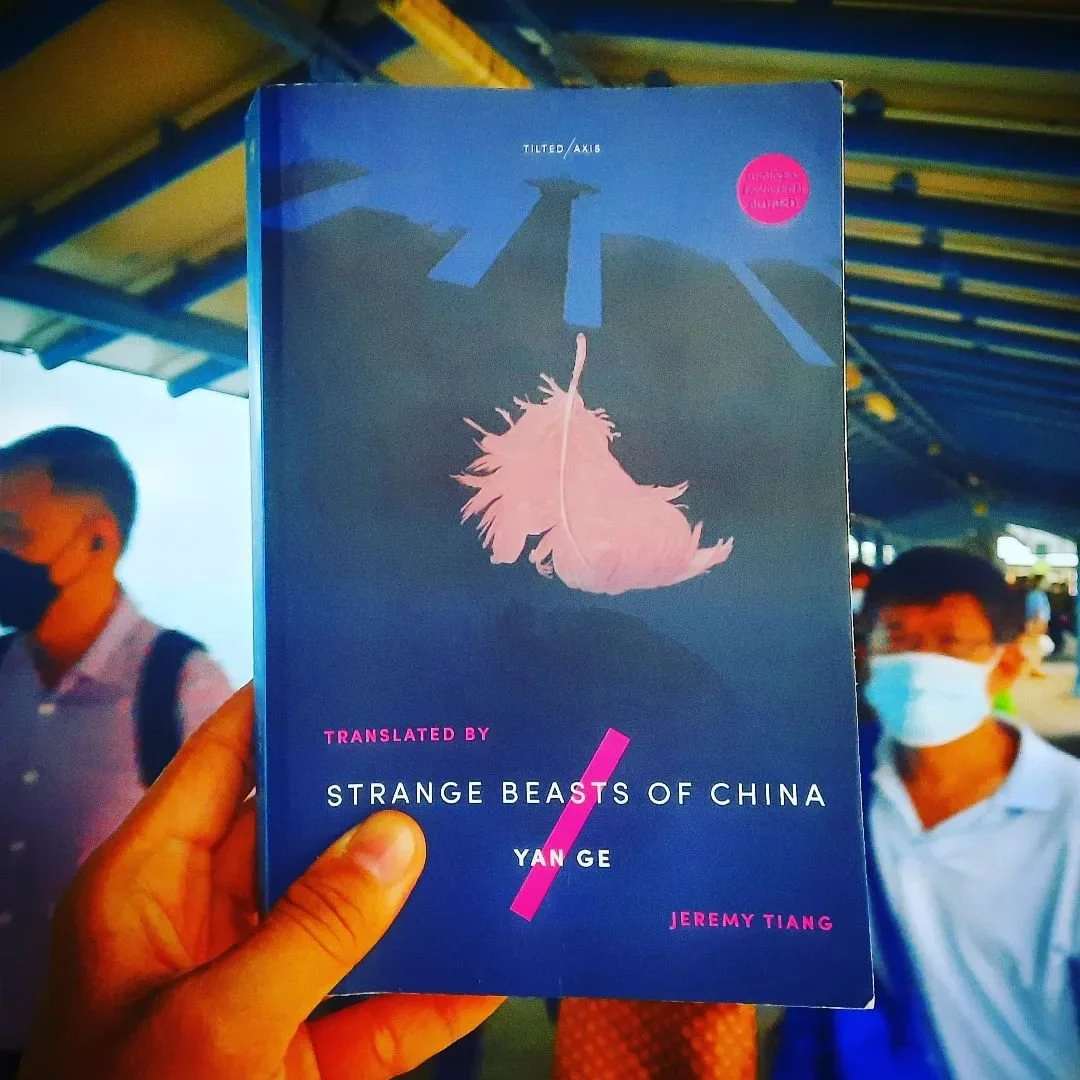

Strange Beasts of China, by Yan Ge

Translated by Jeremy Tiang

Tilted Axis Press, 2020

Ah, what a masterpiece. First published in 2006 as《异兽志》, this novel takes the form of interlinked short stories, all set in the decidedly second-tier city of Yong'an, where our POV protagonist, an unnamed female author, writes fictions in the newspapers about the almost-human creatures who live in her midst.

Now, these aren't traditional mythical creatures—no qilins or centaurs among them—but wholly made-up beings whose appearances approximate that of humans, who are sometimes said to have descended from conquered peoples & can often blend into crowds, but whose life cycles are astonishingly different, metamorphosing into birds and trees, parasitically consuming human flesh or emotions, suffering persecution from society and decay from within, yet still breeding and falling in love, or something like it, w our human characters.

The stories make me grasp for tenors to the metaphors—surely this represents Chinese ethnic minorities, or an oppressed class, or foreigners?—but nothing quite sticks. What's constant is this almighty sense of urban loneliness, as our protagonist returns and returns to the godforsaken Dolphin Bar to drink herself sick, unable to understand that her handsome friends genuinely do care about her. It’s spec fic that's less about fantastical escape than embodying self-destructive emotions; less about consistent worldbuilding than subverting our intuitive sense of culture (though characters reference Zhuge Liang and other figures from classical history, an archaeologist at one point proudly proclaims that his dig is uncovering the city's oldest ruins yet, from 68 years in the past).

The Queen of Jasmine Country, by Sharanya Manivannan

HarperCollins Publishers India, 2018

This novel, too, is f*cking exquisite. It's a retelling of the life of the 8th-century Tamil poet-saint Andal, one of the most beloved of the twelve Alvars, known for her magnificent hymns to Vishnu. And it's utterly delicious—full of the dense, sensual erotic lyricism that the author's known for in her own poetry and short fiction.

I've been curious about this novel since Bras Basah Open referred to it at their SWF 2019 talk “Philosophical Explorations of Bhakti (Devotion) in Indian Literature”. Ordered it from the Kolkata-based Storyteller Bookstore a month back after Amazon’s closure of their Indian publishing arm Westland Books, and the impending destruction of loads of important titles. (The store’s easy to find on social media, and they ship internationally—plus, the books are at low low prices! Check ‘em out!)

What's most precious is the imagining of Andal (here known by her pre-canonisation name of Kodhai) as an un-extraordinary 16-year-old girl, born into privilege as the daughter of a land-owning poet and having miracles ascribed to her name, but still fundamentally a teenage girl growing up among girls—shades of Apple TV's Dickinson. She's unusual in her time for scribbling poetry on palmyra leaves, poetry that will echo through the temples of eternity; unusual for even having been taught to write. But she’s also a teen with little agency, with no right to choose her own groom, who (the author tricks us a little here) doesn't actively rebel against her society, instead searching out conventions she can find strength in, learning folk rites from the low-caste gopis/cowherding girls, entering the great Pongal carnival at Madurai... and only having miracles happen to her in her dreams and the dreams of others.

But here's another thing I cherish: it's an example of how contemporary Anglophone fiction can still meaningfully engage with the classical tradition—I kept getting callbacks to my previous readings in foundational Tamil works like Kuruntokai and Shilappadikaram—all while suffused with a 21st-century feminist, sex-positive, clear-eyed view of the world. Yes, there are advantages to reading your own socio-geographical region in depth.

Ng Yi-Sheng (he/him) is a Singaporean writer, researcher and LGBT+ activist. His books include the short story collection Lion City and the poetry collection last boy (both winners of the Singapore Literature Prize), the non-fiction work SQ21: Singapore Queers in the 21st Century, the spoken word collection Loud Poems for a Very Obliging Audience, and the performance lecture compilation Black Waters, Pink Sands. He recently edited A Mosque in the Jungle: Classic Ghost Stories by Othman Wok and EXHALE: an Anthology of Queer Singapore Voices. Check out his website at ngyisheng.com.

If you’ve enjoyed reading this article, please consider making a donation. Your donation goes towards paying our contributors and a modest stipend to our editors. Singapore Unbound is powered by volunteers, and we depend on individual supporters. To maintain our independence, we do not seek or accept direct funding from any government.

In Taiwan Travelogue, ‘twinned souls… are at once lost, but also found, in translation.’ A review by Eunice Lim.