#YISHREADS June 2022

By Ng Yi-Sheng / @yishkabob

Once again, I’m shifting gears with my column! This month, rather than focussing solely on Asian literature, I’m casting my gaze upon the wide, wonderful world of global speculative writing. (Not just speculative fiction—I’ve got a poetry collection listed below!)

A few readers among you might still cast aspersions upon the traditionally low genres of sci-fi and fantasy. If this is the case, poor you! You’re sabotaging yourself with your snobbery! Even poorly written SFF can stimulate and expand the imagination, and the good stuff is out there in abundance, often drawing from the vast wealth of non-Western folklore and tradition.

Furthermore, over the past decade the spec fic scene’s been the site of some of the most dynamic and urgent debates about diversity, equity, and inclusion. As a result, it’s become way more international. Lavie Tidhar writes a bit about this in his introduction to The Best of World SF: Volume 1 (which I’m included in): how he once struggled to convince publishers to include Aliette de Bodard, Silvia Moreno-Garcia, and Nnedi Okorafor. “Between them, now, these writers are science fiction,” he says. “They have the awards and the hardcovers in the bookstores and the film and TV deals.”

So here’s a sampling of some of the world SF I’ve been reading recently, from Singapore and beyond. Any further recommendations from wherever you call home?

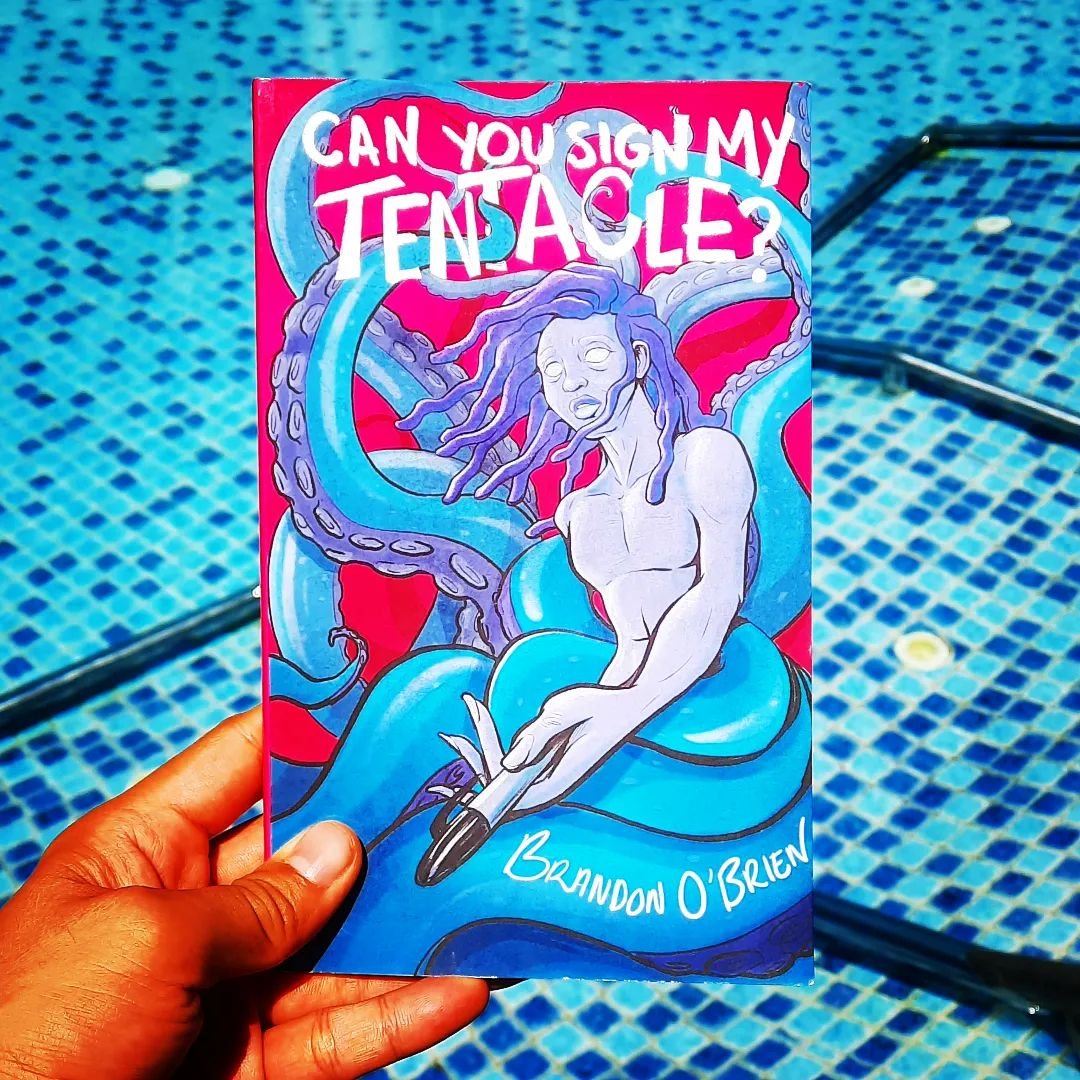

Can You Sign My Tentacle?, by Brandon O'Brien

Interstellar Flight Press, 2021

I discovered this poet during this year’s Flights of Foundry online SFF festival, when he was featured on the panel “Black Speculative Poetry: Afrofuturism, Afrofantasy, and More”. He’s a Trinidadian guy who's in love with the Cthulhu mythos but thoroughly aware of HP Lovecraft's racism and the way notions of monstrosity have been used to dehumanise Black men.

Nevertheless, he’s found a way to embrace cosmic horror in these poems. In works like “Hastur Asks for Donald Glover’s Autograph” and “Cthulhu Asks for Kendrick Lamar’s Autograph”, he imagines the Great Old Ones enthralled by hiphop celebs, by Black suffering and Black creativity—after all, he writes in an afterword, “even if we were as ants to such gods, you would imagine they respond the same as we do when we learn that ants can carry so many times their own weight, and withstand forces many times greater still.” He’s also drawing on Caribbean and Black lore in “the lagahoo speaks for itself” and “tar baby”, faux academese and the magical sci-fi of eroticism in “The Metaphysics of a Wine, in Theory and in Practice”, the raw ache of losing a gay lover in “time, and time again”.

In all of these, he’s experimental in form, language, and perspective, referencing a breadth of texts (more pop culture than dead white men, but hell, more than I can grasp), deep with soul and belonging. Makes me realise that there's way more complexity than I thought among poets who choose to publish in SFF journals rather than university presses. Maybe our postcolonial profs oughta start teaching this stuff rather than pledging allegiance only to VS Naipaul, Derek Walcott, and EA Markham?

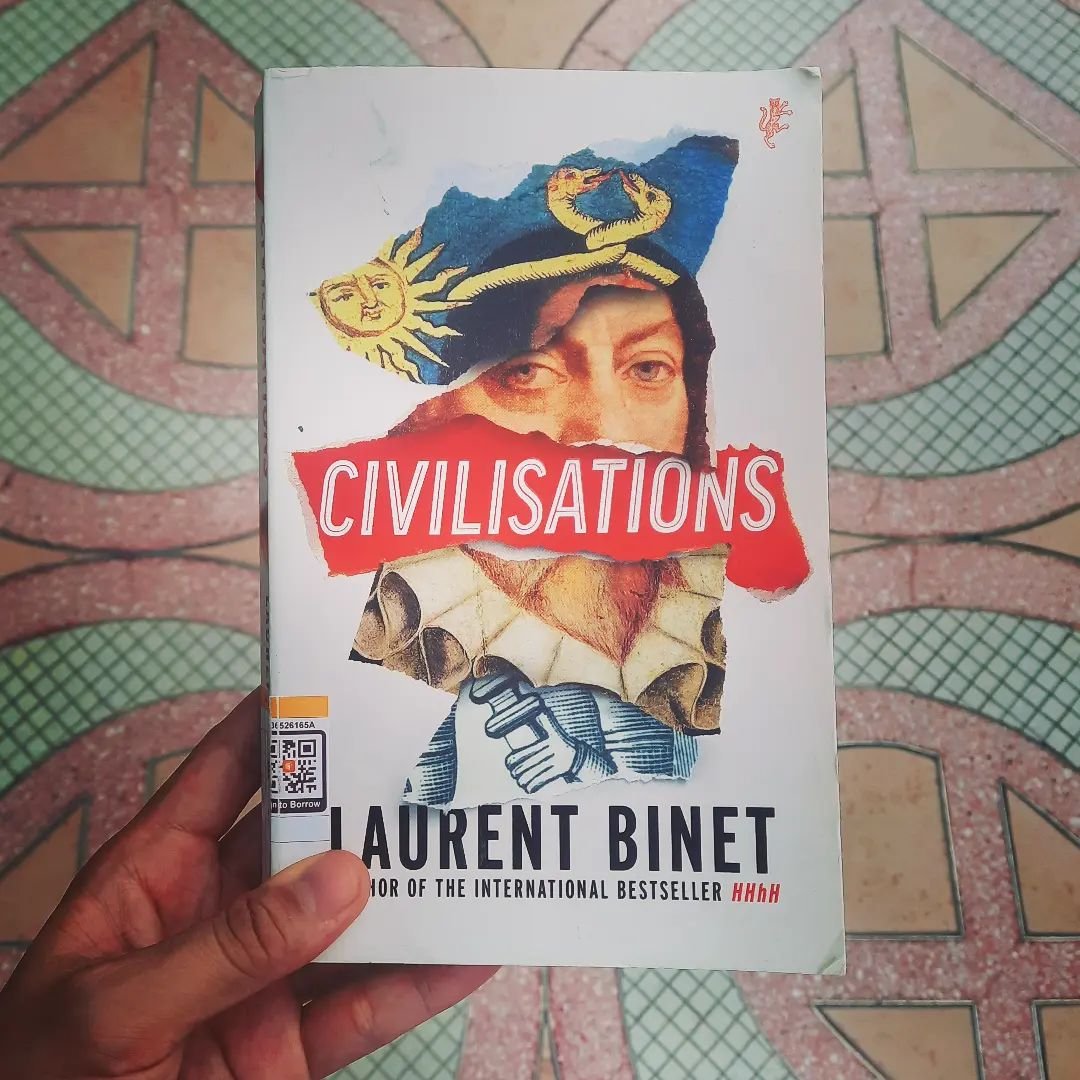

Civilizations, by Laurent Binet

Translated by Sam Taylor

Vintage, 2021

Check it out! It's a 2019 French alternate history novel, imagining a timeline in which the Native Americans colonised Europe!

This isn't the most radical of ideas: I've read similar forays in the form of Orson Scott Card's Pastwatch: The Redemption of Christopher Columbus and Kim Stanley Robinson's The Years of Rice and Salt. Perhaps the biggest shift is that Binet comes from literary fiction rather than SFF, plus he's the son of a historian, so there's much made of the allusions to genuine historical sources, both in terms of style and content.

The first section, “The Saga of of Freydis Eriksdottir”, is transparently based on The Vinland Sagas—she really was a daughter of Erik the Red who travelled to North America and carried out brutal acts of violence, so the scenario of her fleeing to the Caribbean with her men, animals, and germs, managing to profit at others' expense all the way, is thoroughly believable. The second, “The Diary of Christopher Columbus”, is likewise based on the explorer’s original diaries—and oh, what joy to see this cruel would-be-conqueror hunted and stripped by the very indigenous peoples he sought to enslave, blinded and naked in the court of the Taíno queen Anacaona, where he teaches her daughter his Castilian language.

The third section, “The Chronicles of Atahualpa”, makes up the bulk of the book. Here we see Atahualpa, the Inca emperor deposed by Pizarro, fleeing his brother Huascar, all the way from Quito to Haiti... where his men mend Columbus's old caravels, sail all the way to Lisboa (which is in shambles after its 1531 earthquake), and rapidly set up court, relying on Anacaona's daughter Higuenamota as translator, playing the European powers against each other just as they in reality played Native American powers... and even capturing Holy Roman Emperor Charles V in the exact same way Pizarro captured Atahualpa! I learned the details of that scene from Jared Diamond's Guns, Germs, and Steel, but there're loads of other figures appearing whom I learned about from A-Level History or Columbia's Contemporary Civilization curriculum or pop history... Juan Gines de Sepúlveda, Lorenzo de Medici, Marguerite of Navarre, Martin Luther, Michelangelo, Cuauhtémoc... Even Henry VIII ends up converting to the Inca religion, since it allows him to set up a temple full of royal mistresses!

The fourth section's a little weak, TBH. “The Adventures of Cervantes” shows us Miguel de Cervantes and El Greco trekking through a colonised, hybridised Europe, eventually taking refuge in the castle of Montaigne. But this colonisation is represented as relatively benign, and there's this sense that Binet, for all his learning, doesn't really get what it's like to be a colonised/postcolonial subject. Still, this book is a helluva payoff for being a history nerd.

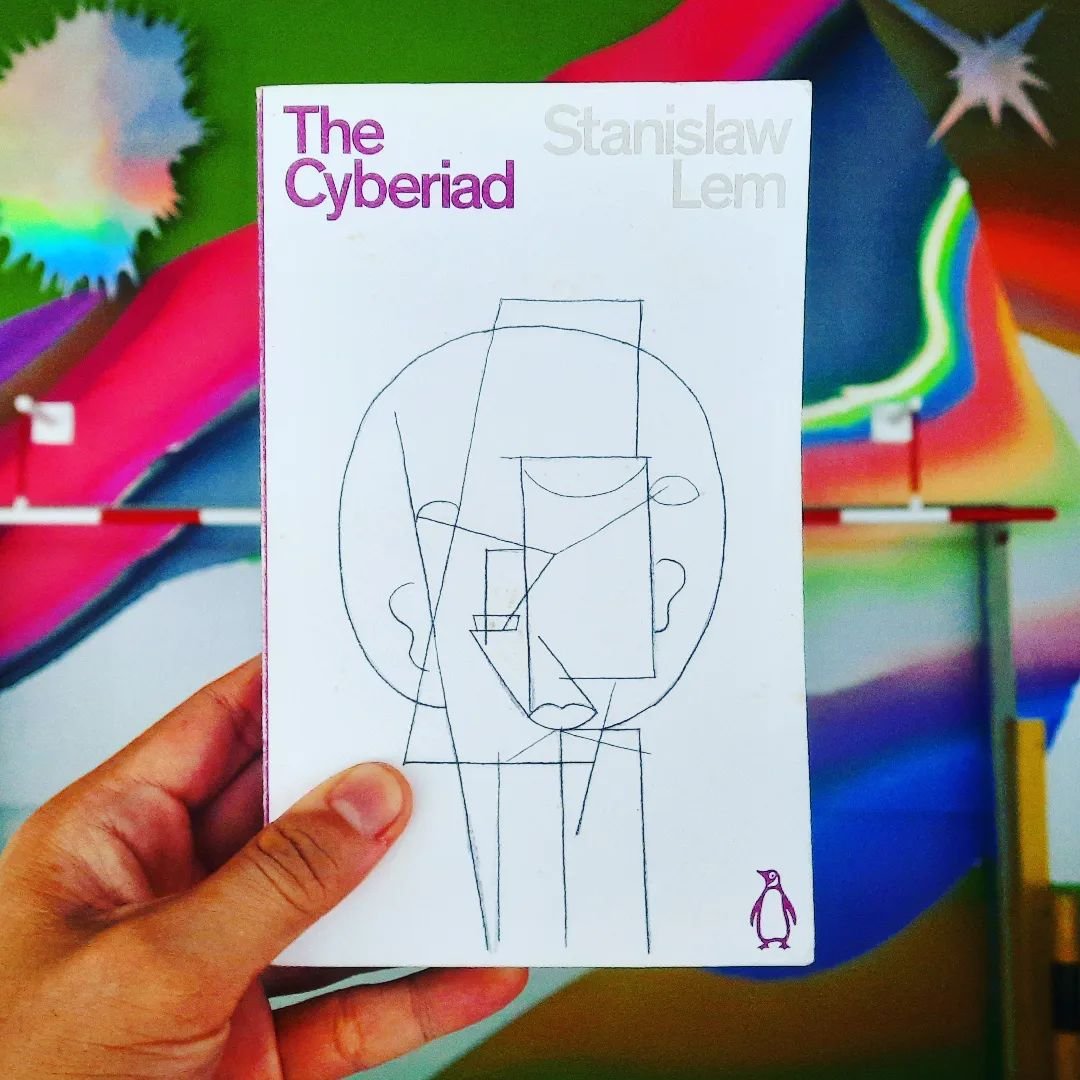

The Cyberiad, by Stanislaw Lem

Translated by Michael Kandel

Penguin Books, 2020

Damn, this is a riot! Made up of interlinked and nested stories, this 1965 novel centres on the misadventures of two crazy inventors, Trurl and Klapaucius, as they conjure up mad machines that do everything from switching minds to bombarding cities with babies to recreating the entire history of the universe just to generate good poetry. And it's all set in a pseudo-medieval cosmos of tyrannical kings and fair princesses and conniving advisors, most of whom (including the inventors) are eventually casually revealed to be robots. (At first, you think the stories of people rusting through are metaphorical, but nope!)

It's tempting to classify this as science fantasy, given the fabulistic, even folkloric flavour of the stories. But Lem really knows his scientific jargon, peppering his tale with gloriously Carollian/Nabokovian combinations thereof in his inventors' pseudobabble (amazed as well by the virtuosity of the translator). The logic games (including the whole question of whether a simulated kingdom-in-a-box is populated by sentient creatures, which genuinely inspired the game SimCity) have also led some to compare his work to Borges, but the tenor's altogether different—while Borges mourns the human condition, aspiring to inhuman order, Lem revels in the deliciousness of chaos, to which he believes even the highest of civilisations is destined/doomed.

In short, this is a kind of sci-fi I haven't read in a while, closer to Calvino’s Invisible Cities than most of the space opera out there—yet also strangely akin to my own stories, “Little Red Dot” and “Xingzhou”, in its absurdities. As they say, one of the great joys of reading books is discovering friends you never knew you had.

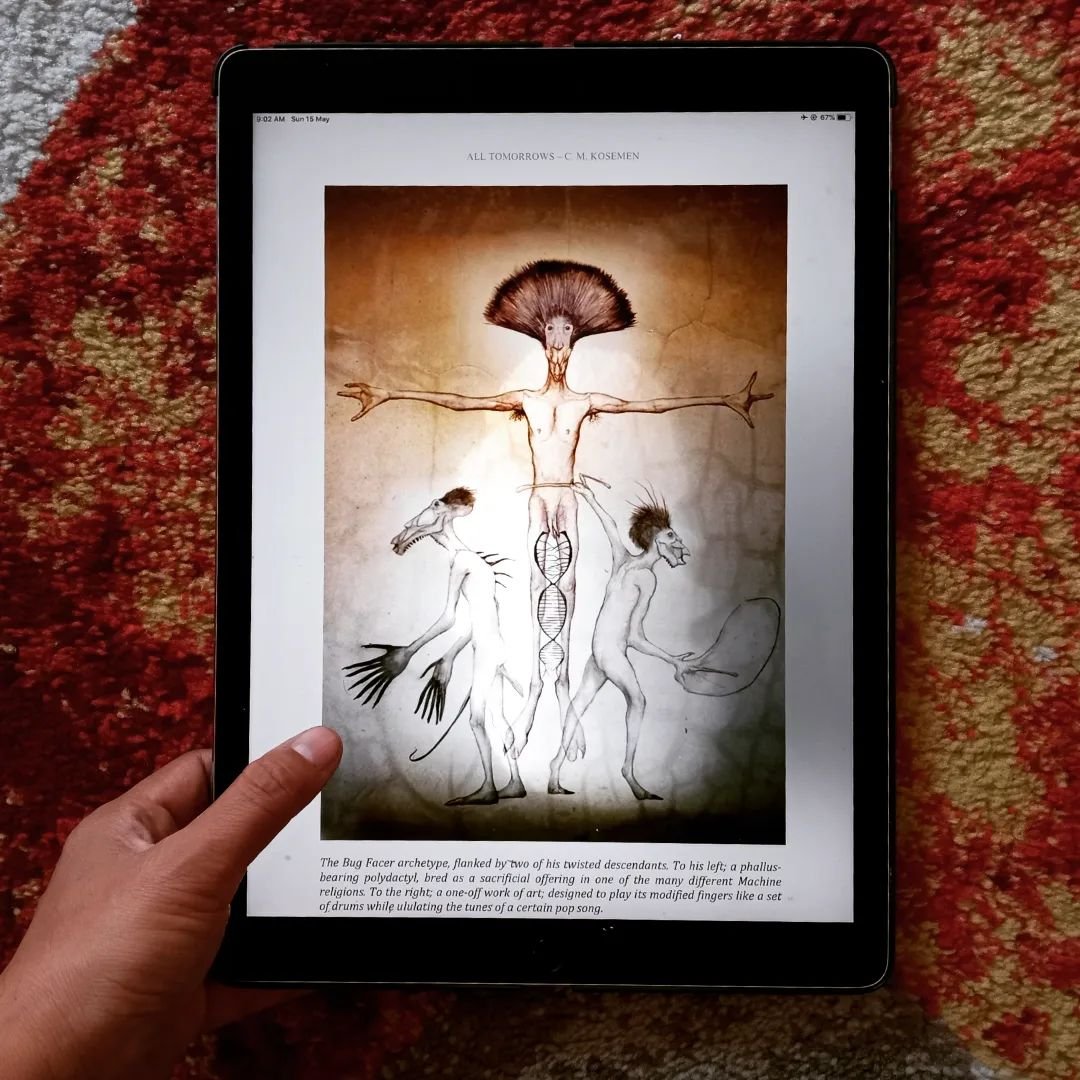

All Tomorrows: A Billion Year Chronicle of the Myriad Species and Mixed Fortunes of Man, by C.M. Kösemen

Self-published, 2006

Not sure who gave me the link to this free pdf book from 2006, but damn, it's compelling. Basically, this Turkish artist decided to imagine what the billion-year future of human evolution might look like—my copy lacks a cover, so the pics are his illustrations to his chronology, from the first expansion of the species to Mars to the multi-planetary wars, genocides and deliberate genetic manipulations wrought by humans, aliens and their multispecies descendants.

Makes you wonder a little about what the future looks like, depending on whether you've got an American historical perspective (manifest destiny) or a Turkish one, informed by untold layers of civilisations and conquests, where your heritage is both that of the coloniser and the colonised. Or am I essentialising the author to his nationality?

You can download the work yourself for free at the author’s website!

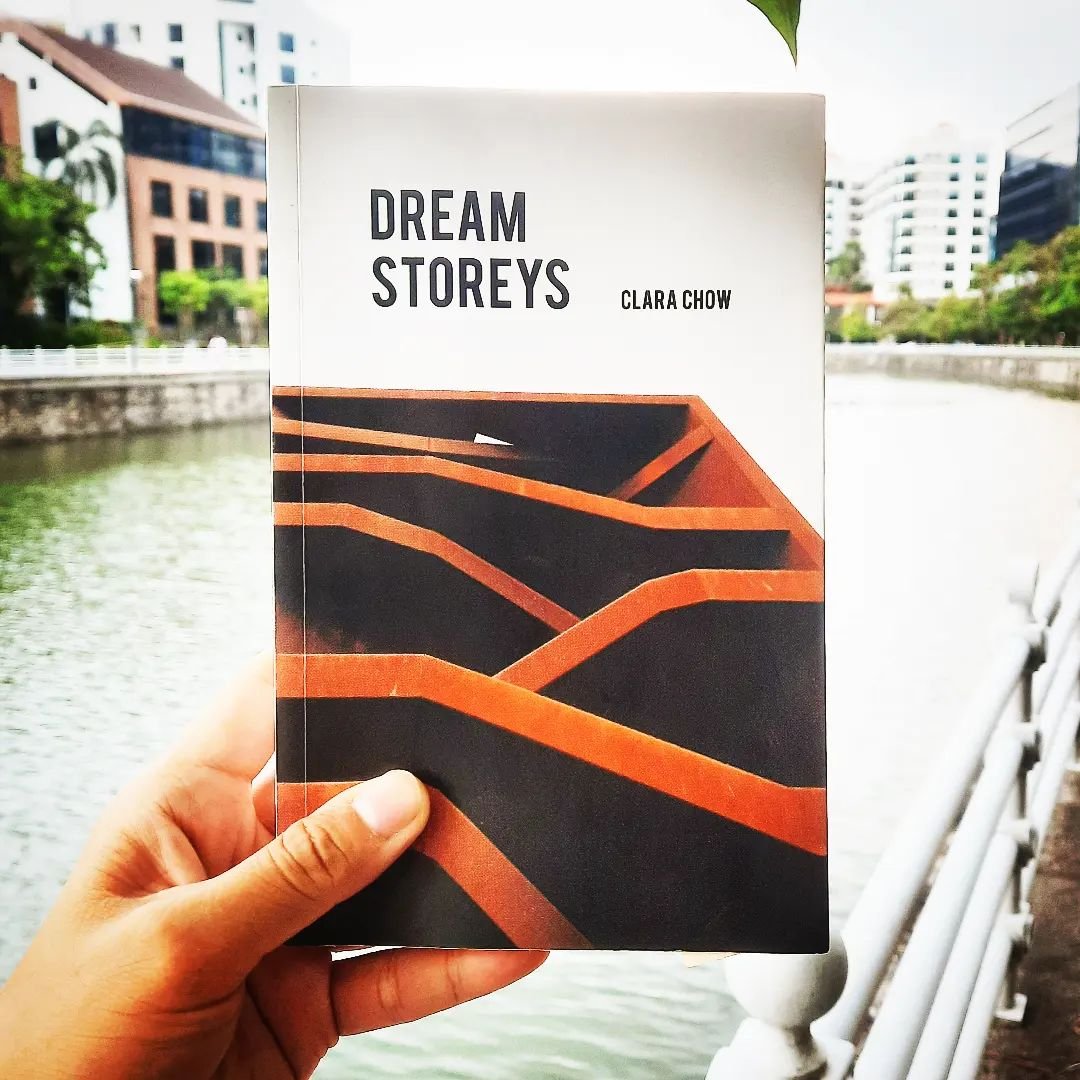

Dream Storeys, by Clara Chow

Ethos Books, 2016

This collection didn’t really register on my radar when it came out, which is kinda surprising: it’s spec fic, plus it’s one of those really cool interdisciplinary projects—the author interviewed architects about the unfulfilled projects they wished they could’ve built, then wrote stories inspired by their replies. Seems it began organically too, through a conversation with a friend, Yen Yen Wu, which yielded “The Mall”, about a shopping complex that’s designed to self-destruct from wear and tear, told from the POV of a dropout from Singapore’s path to success.

Chow’s premises are honestly very cool: modular playgrounds that dangerously disappear kids to other dimensions in “The Mountain”, housing estates turned into a dinosaur fossil theme park in “Bare Bones”, a symbiotic old folks’ home-cum-orphanage, labyrinthine and full of treasures, in the boughs of a 40-metre tree in “Tree House”. But her execution doesn’t always thrill me: some stories are slow to pull you in, strangeness seems to dwindle rather than escalate, and her roots in literary fic rather than SFF are achingly visible—there’re so many needless references to great classics (Orwell’s Why I Write; Eliot’s Middlemarch), and almost all the tales end up being about middle-class Chinese people realising they’re sad.

My favourite story is the final one, apparently conceived without an interview as a prompt, but set in the same world as “The Mountain”. “The Wheel” envisions a future Singapore in which the Singapore Flyer is repurposed as a hellish panopticon for political prisoners, sleeping all day upright as the derelict chakra turns and burns in the scorching sun… and then crazier things happen. This is full-on dystopian, more so than the more everyday dissatisfactions of the other tales— and as an activist, I’m sorry to say it represents a Singapore that’s all too familiar to my eyes.

Ng Yi-Sheng (he/him) is a Singaporean writer, researcher and LGBT+ activist. His books include the short story collection Lion City and the poetry collection last boy (both winners of the Singapore Literature Prize), the non-fiction work SQ21: Singapore Queers in the 21st Century, the spoken word collection Loud Poems for a Very Obliging Audience, and the performance lecture compilation Black Waters, Pink Sands. He recently edited A Mosque in the Jungle: Classic Ghost Stories by Othman Wok and EXHALE: an Anthology of Queer Singapore Voices. Check out his website at ngyisheng.com.

If you’ve enjoyed reading this article, please consider making a donation. Your donation goes towards paying our contributors and a modest stipend to our editors. Singapore Unbound is powered by volunteers, and we depend on individual supporters. To maintain our independence, we do not seek or accept direct funding from any government.

In Taiwan Travelogue, ‘twinned souls… are at once lost, but also found, in translation.’ A review by Eunice Lim.