The Presence of Another World

by Annina Zheng-Hardy

Review of Notes from the Birth Year by Mia Ayumi Malhotra (USA: Bateau Press, 2022)

Laxmi Hussain - Best Seat in the House 04 (left) and My Eden and Me 01 (2021), Acrylic on birch-wood panels

Image description: A series of two cobalt-blue paintings on square birch-wood panels. The panel on the left shows the body of a nude woman breastfeeding her baby, and the right panel features the woman’s point of view with the baby sitting on a pair of cross-legged thighs.

Mothering — chronically devalued both as labor and as artistic inspiration — is a fraught subject to write about. To discuss it in too saccharine or awestruck or celebratory a way is to risk being read as sentimental, but be too ambivalent, and the writer risks being labeled as monstrous or even abusive. Women who are not mothers cannot escape these narratives either: whether you opt in or opt out, whether you can or cannot, you are either selfless or selfish, either loving or cold.

Still, the clear “before” and “after” of motherhood has made it a widespread subject of literary inquiry. Rita Dove, in Mother Love (1995), grounded the mythic drama of being mother and daughter in a world that doesn't make such intimacies easy. Eavan Boland's poetry posits motherhood as a noble, holy and morally elevated pursuit, as in the poem "Hymn" where she writes,

Here is the star

of my nativity:

a nursery lamp

in a suburb window

Sylvia Plath explored maternal ambivalence in Three Women (1962), which represents, in three voices, a joyous mother ("What did my fingers do before they held him?"), a callous mother ("My daughter has no teeth. Her mouth is wide. / It utters such dark sounds it cannot be good"), and a grieving woman who has failed to become a mother as a result of repeated miscarriages.

Mia Ayumi Malhotra’s pamphlet, Notes from the Birth Year, winner of Bateau Press’s 2021/2022 BOOM Chapbook contest, uses form to illustrate motherhood's profusions — alternating between poems of long lines separated with white space and poems written so that the words rush down the page, unbroken by stanzas, breathless in their recounting of events. The poet muses over this change in “On Form”: "When I became a mother, my lines began to grow less mannered, less sculpted— and this wild, itinerant prose did not adhere to shapelines". Throughout Notes on a Birth Year, Malhotra, the poet turned mother-&-poet, travels between these two modes: one of pointillistic, measured lines and one of waterfalls of sensation, both of which are necessary for drawing us into her intimate world. At the heart of this world is the common yet particular experience of seeing the heartbeat you housed first within you ("On Worlds That Leave Us": “I felt a sudden coldness. Strangely alone in my body, carrying not two heartbeats, but one.”) suckle from you and then get on her own two feet and speak for herself. It is a world that — like marriage, like one's dreams, or like a drug trip — cannot ever translate fully to outsider spectatorship. There are, of course, many ways to mother and to be a mother, just as there are many ways to be of a lineage and to be a daughter, and many of them do not include gestation or breastfeeding, but these are the sensations, both physical and metaphysical, explored in exquisite detail in these poems. Malhotra's motherhood shares the reverent and generous voice of a poet like Liz Berry, who describes how she entered "the Republic of Motherhood / and found it a queendom, a wild queendom" where she and her child are "like new sweethearts, / awake and fretful / through the shining hours, close as spoons / in the polishing cloth of dawn."

Laxmi Hussain - Best Seat in the House 01 (2021), Acrylic on handmade Bhutanese paper

Image description: A bronzy-orange and cobalt-blue painting on rough-edged Bhutanese paper of a mother carrying a baby in her right hand. Both the baby's and mother’s heads are not in the frame.

Malhotra described her first book, Isako Isako, which came out with Alice James Books in 2018, as an inquiry into the way we move through generational time and geographic space amid all that binds us together. Notes from the Birth Year is a sequel in this endeavor; it explores, in her words, "the way motherlabor reconstitutes the elements of one’s being—ontologically, physically, metaphysically […] it represents the next segment of my exploration of the Motherline. It turns from the history of my female line to the embodied experience of female lineage in my own life and, consequently, in the lives of my daughters." And so it is unsurprising, then, that a theme in these poems is also that of memory — the ocean's gritty memory, episodic memory, language as an instrument of memory, perfect memory, and thwarted memory, as in the poem "This House is So Full of Ghosts", where:

… Memory

is a winter pond, seven feet deep. Koi turn

slow circles, glinting like hammered gold. I reach

for the flat, cold surface and almost touch

her face, but it's only a reflection.

These final lines evoke the members of our families we never met, never knew but only in gnomic fragments taken from someone else's memories. This collection, so predominantly about birth and the beginnings of life, aches with loss as well. After all, our mothers and grandmothers can't live forever. And yet, in this poem, our shallow pools of memory, while never able to bring touch back to life, aren't as empty as they might seem, there's something there glinting beneath the surface.

In "On Mind and Memory," one of several poems that use borrowed lines, Malhotra reflects on this barbed aspect of storytelling — the relation of a shared memory only the teller can recall. Here, the mother tells the child about "when you were a baby and when you were little," sharing stories of firsts and of bedtime rituals that the child, out of babyhood, no longer remembers. In so doing, the mother feels "it's as though I'm telling her about someone else's life. Which I am, in a way." Indeed, we are all prisms, all with fragments of ourselves obscured— by necessity, by the quirks of remembering and forgetting — in the memories of others, who are also constantly remembering and forgetting, editing and overlooking, memorializing and neglecting.

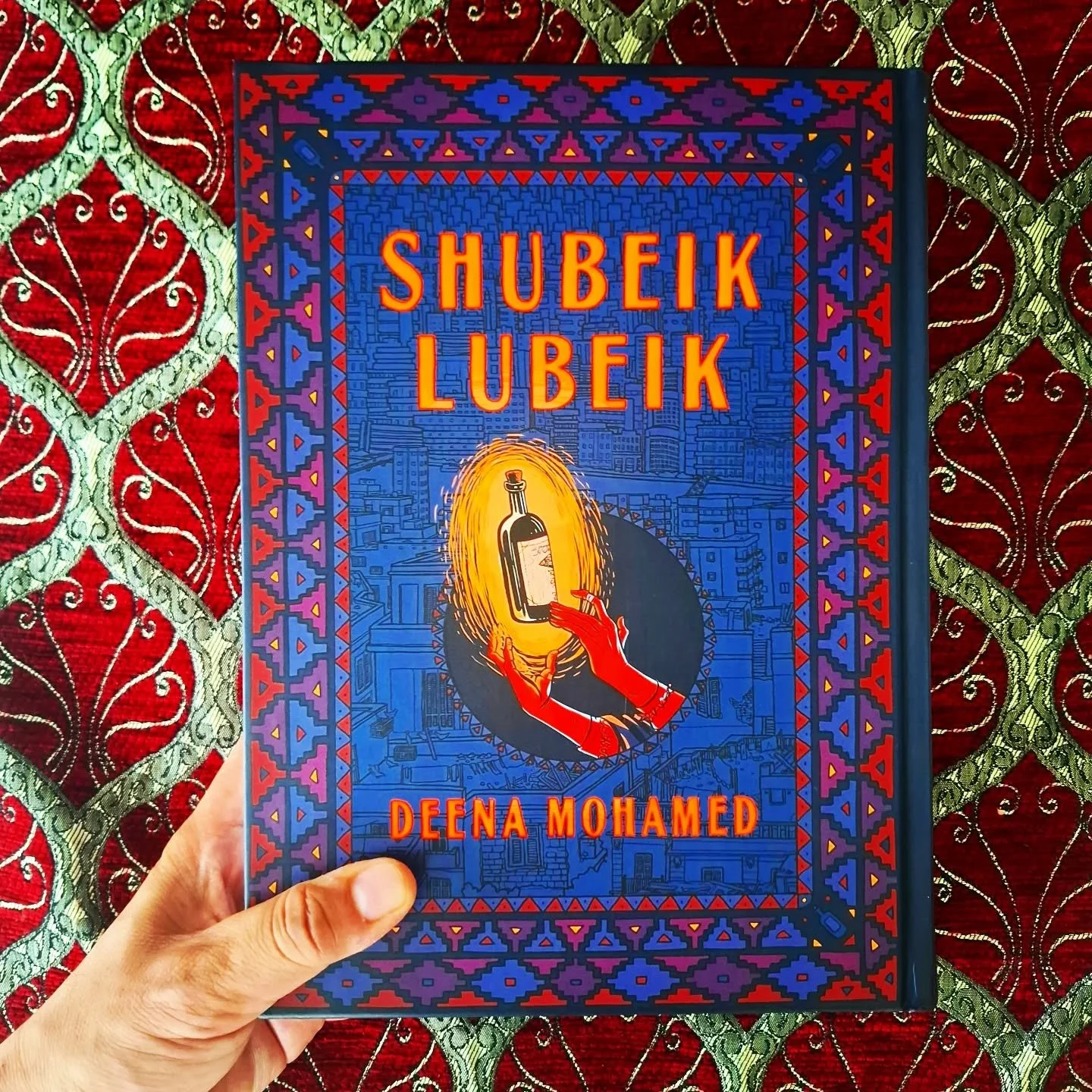

Laxmi Hussain - Untitled Motherhood Drawing 1, 2 & 3 (2022), pastel and acrylic on paper

A series of three orange, continuous-line drawings on a roughly painted cobalt-blue background of a nude woman carrying her baby.

Some mother-poets are deeply concerned with the grotesqueness of their fecundity, as Natalie Shapero is in Hard Child: "I bought the bound ONE THOUSAND NAMES FOR BABY, made two lists: one if she’s born breathing one if not." Malhotra's pamphlet is less absorbed with these worries, but the world of motherhood is nonetheless disorienting, both for the newborn and for the well-seasoned human moving through different stages of life. In "On Need", the speaker recalls the process of weaning: when she finally emerged from being so tethered to her child, so needed, the baby was "dazed, it was as though from a cocoon, organs dissolved into sticky fluid. A roaring in the ears." Two poems later, "On Weaning" compares weaning to boarding a plane alone, something that at one time would have seemed natural but that now means "a shock, that I am leaving it all behind—freeways, blocky tracts of gray. The merged self we make: mother, mouth, milk." Leaving the ground as the plane takes off recalls leaving her baby and the hold of necessity—of gravity—that bound them together.

The process of weaning is as strange as the process of latching, which for some comes so naturally and for some is so impossible. Malhotra describes the first night after beginning the weaning process, the first night of not feeding her baby from herself, when she instead feeds herself from herself: "I wake to a twinge in my left breast. I huddle over the bathroom sink, pump pressed to chest. Nipple elongated, silky with milk. // How tightly we are bound. By the hours, sliding past. My body’s milky secretions. // With no one else around, I tip my chin and drink it down. A single warm, creamy mouthful. I am drinking myself in, a new sensation." An oft-heard refrain from parents is that they can no longer remember life before their child or children were born, and this moribund pre-mother self finds its way into many motherhood poems. For example, Brenda Shaughnessy, in her epic poem Liquid Gold, thinks of "Me, this puddle of a middle, this utilized vessel, cracked hull, divine design. It’s how it works […] But what about me? I whisper secretly and to think, around these parts used to be the joyful place of sex, what is now this intimate terror and squalor." Just so, we never find out where Malhotra’s plane lands. She describes "Continents, seas—the ocean’s blue sprawl, its restless churn. At takeoff, I feel the air around me resist. My belly tugs tight, as though tied to land by an umbilical cord. In flight I lose all sense of where one body ends and the next begins."

Reading these poems, documentations of the quotidian, I feel as if I am sitting in a dark room, the consciousness of another bathed in the glow of stage lights. Mother and child are embracing, baking, going for a walk, and we, the readers, are watching from the darkness beyond the stage’s borders. Malhotra, who grew up in Laos and Thailand to Japanese-American parents, knows, as she puts it in one of the pamphlet's final poems, "how world-haunted we all are". As an antidote, this pamphlet keeps us ensconced, for a moment, in its holding. In doing so, it shares with us the overwhelming disjointedness of early motherhood, with its constant unfolding, the way it presses against prior knowledges and outer conditions. Its contribution is to show us how, always, "we live in the presence of another world, faces lit from the inside. So much is mystery. So much we do not know."

Annina Zheng-Hardy (she/her) is a poet living in London. Her poems and short fiction are forthcoming or have appeared in Joyland, The Offing, bath magg, Honey Literary, and elsewhere.

Laxmi Hussain is a London-based artist whose work exists somewhere between the abstract and the realistic. Having studied architecture, she enjoyed and excelled at the drawing and fluid art techniques within the course and this became a basis from which to explore all aspects of drawing.

After becoming a mother, Laxmi began drawing daily and sharing her work on Instagram, finding artwork to be a valuable means of reclaiming her own identity amid the emotional blurrings of motherhood. These experiences of motherhood can be seen clearly within her work, as well as exploring themes surrounding the body, specifically looking to challenge negative associations and normalise representation of all types of bodies within art.

If you’ve enjoyed reading this article, please consider making a donation. Your donation goes towards paying our contributors and a modest stipend to our editors. Singapore Unbound is powered by volunteers, and we depend on individual supporters. To maintain our independence, we do not seek or accept direct funding from any government.

In Taiwan Travelogue, ‘twinned souls… are at once lost, but also found, in translation.’ A review by Eunice Lim.