Recommendation Letter for Iqra Islam

By Niaz Zaman

Nazlee Laila Mansur - Girl on Rickshaw (1994), Oil on canvas

Image description: The painting depicts a girl with curly hair and pale skin, peering out between curtains. In the middle of the painting, she turns her head around and her gaze is downcast. She wears an orange top and a red shawl. Her right hand pulls back the right half of the curtains. On the left side of the painting, the other piece of curtain drifts up. The curtains are decorated with patterns of bright flowers and white doves.

Dear Dr Mountjoy,

Iqra Islam has applied to the doctoral programme at the Department of Comparative Religions, Fernham University, and has requested me for a recommendation letter.

She wants to use her training in literary/critical theory to interpret the Quran as an epic, in the tradition of primary epics transmitted orally before being written down. She is particularly interested in interpreting the Quran as the last book in the tradition of the three books accepted by Islam. I appreciate her interest as I believe that we need critical and analytical approaches to the Quran not just as a religious book but as a piece of literature.

Iqra completed her MA in English Literature from the University of Dhaka in 1996. Since then she has been teaching English language and literature at different community colleges in the US. Without a doctoral degree it is not possible to get a position at a US university. The question is why she did not take up doctoral studies in the US where, as you are aware, most doctoral students fill the instructional pool as TA’s. Unfortunately, with four small children, it was difficult for her to take up a sustained course of studies. I also understand that her husband—whom she married while still a student in Dhaka—was not supportive. Though he had a good job at VOA, he didn’t want his wife to be more educated than he was. In fact, shortly after they both completed their MA in English from the University of Dhaka, he availed of his wife’s British passport to move to the UK. There, after doing some odd jobs, he was able to get a job in the Bangla Service of the BBC. Subsequently, he applied to the VOA and shifted the family there on the basis of his work visa. With the children somewhat grown up and going to all-day schools, Iqra looked around for work. With the gap between her completing her MA and her application for a teaching position, it was difficult for her to get a job. Still, she persisted and finally managed to get a job at Rockville Community College.

The 9/11 attack on the Twin Towers had an adverse impact on Muslims in the US. As you are aware, even bearded Sikhs were attacked by Americans ignorant that Sikhs did not belong to the Islamic fold and that, in fact, during the Partition unrest in 1947, Muslims and Sikhs in north India and the newly-formed state of Pakistan were bitter enemies. In those terrible times, trainloads of Muslims travelling to Pakistan were attacked by Sikhs and the men killed and the women abducted or raped. Meanwhile, Sikh villages in Pakistan were attacked by Muslims and the Sikh villagers killed and their women abducted or raped—if they did not manage to commit suicide first by jumping into wells. (For the impact of Partition on Muslims and Sikhs, you might watch Gadar: Ek Prem Katha and Bhaag Milkha Bhaag.) It was in these circumstances that Iqra’s husband felt that the family might be safer in the UK with its long ties with South Asia. (Unfortunately, despite the two hundred years of British rule, Britain did not quite understand that both Punjabi Muslims and Punjabi Sikhs would be loyal to the British but would not be brothers-in-arms when the land was divided into “Muslim Pakistan and Hindu India.”) Iqra and the children moved back to the UK while her husband stayed on in the US with the VOA.

While the family stayed safe, the marriage fell into trouble. Iqra’s husband became involved with a young colleague of his in the same Bangla service. Things would have continued much like this but the Bengali community is a close-knit one and Iqra got to learn of her husband’s liaison from his colleagues. When Iqra realized that her family had told her the truth when she got married—that the handsome young man had chosen her not for herself but for her passport—she was hurt and angry. She sent him a divorce notice. Under civil law the divorce was valid but under Islamic law Iqra was still believed to be married to her husband. As she had no desire to marry again at the time, she did not pursue him to grant her a talaq.

However, perhaps in a reaction to the antipathy towards Muslims as a result of the Twin Tower attacks, Iqra became more religious, started wearing the hijab and going to the local Islamic Centre to learn more about Islam. This is when she became interested in learning Arabic as a language. Most people in South Asia learn to read the Quran but not to understand the Arabic in which it is written. Iqra thus became more exposed to the religion into which she had been born, but which she hadn’t questioned all these years. The realization that a civil divorce had not granted her full divorce from her husband in the eyes of the community led her to start questioning the rules of the Quran. She had believed that, in many ways, the religion of Islam was far more advanced than Christianity or Judaism—and far kinder to women than Hinduism. Widows were allowed to remarry as were divorcees since the time of the Prophet (Peace Be upon Him). They were allowed a share in the property of their fathers and husbands at a time when married European women could not own property. Still, there were many myths about women in Islam. For example, in Vindication of the Rights of Woman, Mary Wollstonecraft expressed the belief that in Islam, women did not have souls. Even today in America many people believe this myth. Nevertheless, there are instances where Islam or interpretations of the Quran allow women to be treated as second-class citizens. Why is a husband allowed to beat his wife—even if lightly? Why does a woman’s testimony not carry the same weight as a man’s? Why, if there are no children, is a childless wife deprived of a share in her husband’s property? Why are daughters given a smaller share in their father’s property than their brothers? Why, when there are only daughters in a family, are girls deprived of their father’s property? These questions started to bother Iqra.

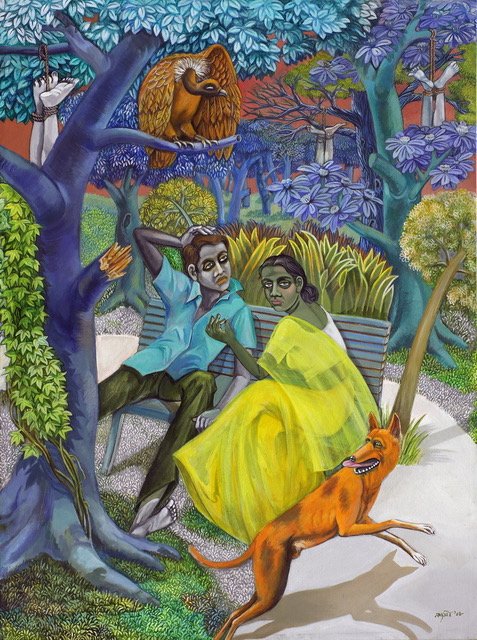

Nazlee Laila Mansur - Lovers and Vulture (2008), Acrylic on canvas

Image description: The painting features a couple sitting on a bench, surrounded by plants and animals. In the middle of the painting, the man with dull-gray skin holds an arm behind his head. He wears a blue shirt, green pants, and is barefoot. The woman has dark-green skin; she sits next to him and holds out her left arm, but turns her head to gaze at the viewer. She wears a bright yellow shawl. They both have solemn expressions. On their left is a purple tree with blue leaves; one of its lower branches is broken. A vulture perches on the tree’s branch. A pair of legs are tied to another tree branch with ropes, and hangs down limply. In the foreground, an orange mammal passes the couple; it looks behind and sticks out its tongue. In the background, trees and bushes are rendered in shades of blue, purple, and green. Pairs of legs hang upside-down from the branches of trees.

You may well ask how this is a reference for Iqra Islam.

I want you to understand the person who Iqra is and why I believe that you should accept her despite her coming from a different discipline and despite the long gap between her final degree and her applying to your graduate programme. She will not write all this in her application letter.

Without understanding her, you will glance briefly over her CV, over her proposal, over her application letter and reject her. I want you to know not only her background but the type of person she is and why she needs acceptance into the programme and financial support if possible.

As I mentioned earlier, Iqra completed her MA in 1996. In other words, I knew her as a student of the University of Dhaka from 1991 when she, her younger—and more beautiful—sister, and a young man named Polash joined the Department of English. Polash was exceptionally handsome and his name—the name of a vermilion flower that blooms in February—truly suited him. (Polash was not his proper name—almost everyone in Bengal and Bangladesh has a “good” name and a calling name. But I can’t remember his formal name.) He stood out in a room of brown skins. It was surprising that Polash should have chosen the darker elder sister over the more beautiful younger one. (We did not know this at the time because we often saw the three of them together—in the corridors or sitting on the shaded sidewalks of the campus.) Though the University of Dhaka was a coeducational university, in the late eighties, men and women did not freely talk to each other on campus—though it was much better than the situation in the fifties when young men had to wait outside the Women’s Common Room with a permission note from the Proctor to be able to meet one of the women students. By this time also women did not have to sit in the first row or cover up their heads—the head covering had been discarded in the 1960’s. However, hijab slowly entered the university as elsewhere in the new millennium.

Unlike western universities, families which send their children to us expect us to look after them like our own children. Hence, it is not surprising when a parent meets the head of the department expressing his or her concern that a daughter has become too friendly with some young man, should be kept under close watch, and not allowed to mix freely with him. Of course, this does not fall within the purview of our duties, but parents persist in thinking that we stand in a paternal—or maternal—relationship to our students and should guide them in life and in their studies, prevent them from going astray.

When Iqra was in her final Honours year—at that time it was a three-year programme—I was the head of the department. I had just finished taking a class and was entering my office room when the Departmental Assistant informed me that a lady was waiting to see me. “She says she is the mother of Iqra.”

The elderly lady sitting in my room did turn out to be Iqra’s mother. She explained to me that the family had returned to Bangladesh when their two daughters entered their teens. “We did not want them to become like the other girls, wearing short skirts or tight pants and going out with boys so we came back.” But now it seemed that all their attempts had been in vain. The parents were not so worried about the younger daughter but they were worried about the elder daughter who had become interested in a most unsuitable young man. Though I attempted to calm her, I explained that it was not possible to forbid the young people meeting. In fact, I explained, restricting them would have an adverse impact. Make them more adamant in their relationship.

Nevertheless, I did promise to see to it that, whenever possible, Iqra would not be given the same tutorial class as Polash. Of course, tutorials had already been distributed and Iqra and Polash fortunately were not in the same tutorials. However, with limited choices for courses, they were in the same classes.

Shortly after the Honours viva, Iqra’s sister told me that Iqra and Polash had eloped.

Both Iqra and her sister had been brilliant students. With their exposure in the UK, their excellent command of both written and spoken English, and their study habits (they did not memorize answers as most of the other students did), they were both supposed to do well. Unfortunately, Iqra’s tutorial grades were going down—unlike the Oxford model on which the tutorial, indeed the university had been founded in 1921, the tutorial had become a grading rather than a teaching tool. Together with the viva marks, the tutorial marks—from two tutors every year—made up 100 marks. Usually, tutorial marks were a good measure of how a student was doing. Despite everything, Iqra did manage to get a second class while her sister got a first.

All three enrolled in the MA programme—in Literature rather than in what was becoming very popular: ELT and Applied Linguistics. When the exams were scheduled, however, Iqra was in an advanced stage of pregnancy. There was no lift at the time to the fourth floor where the examinations were held. There was no question of Iqra climbing four levels to the exam hall, so I allowed her to sit for the four written exams in my room. (There was a sick room on the ground floor for students who were unwell to take exams but, as Iqra said, pregnancy is not a sickness but a state.) I also felt that she would be more comfortable in my air-conditioned office room. (Neither the several classrooms nor the four examination halls were air-conditioned in those days.) The viva was held four days after the exams. Iqra gave birth to a baby boy four days after her viva.

That was the last that I saw of Iqra or Polashthough I did meet her sister from time to time at some conference or the other—she had taken a post at a local college. That is how I kept getting little bits of news about her: about the birth of a second and then a third boy, about her family relocating to the US, about Polash getting a job at the VOA, about the impact of 9/11 on the family, about the breakdown of the marriage. I had no direct contact with Iqra. And then Iqra wrote to me asking for a recommendation letter as she was applying to do her doctoral studies. “You will not remember me,” she began in the letter. But, no, I did remember her very well. Even if her sister had not filled me up on her life after MA, I would still have remembered her.

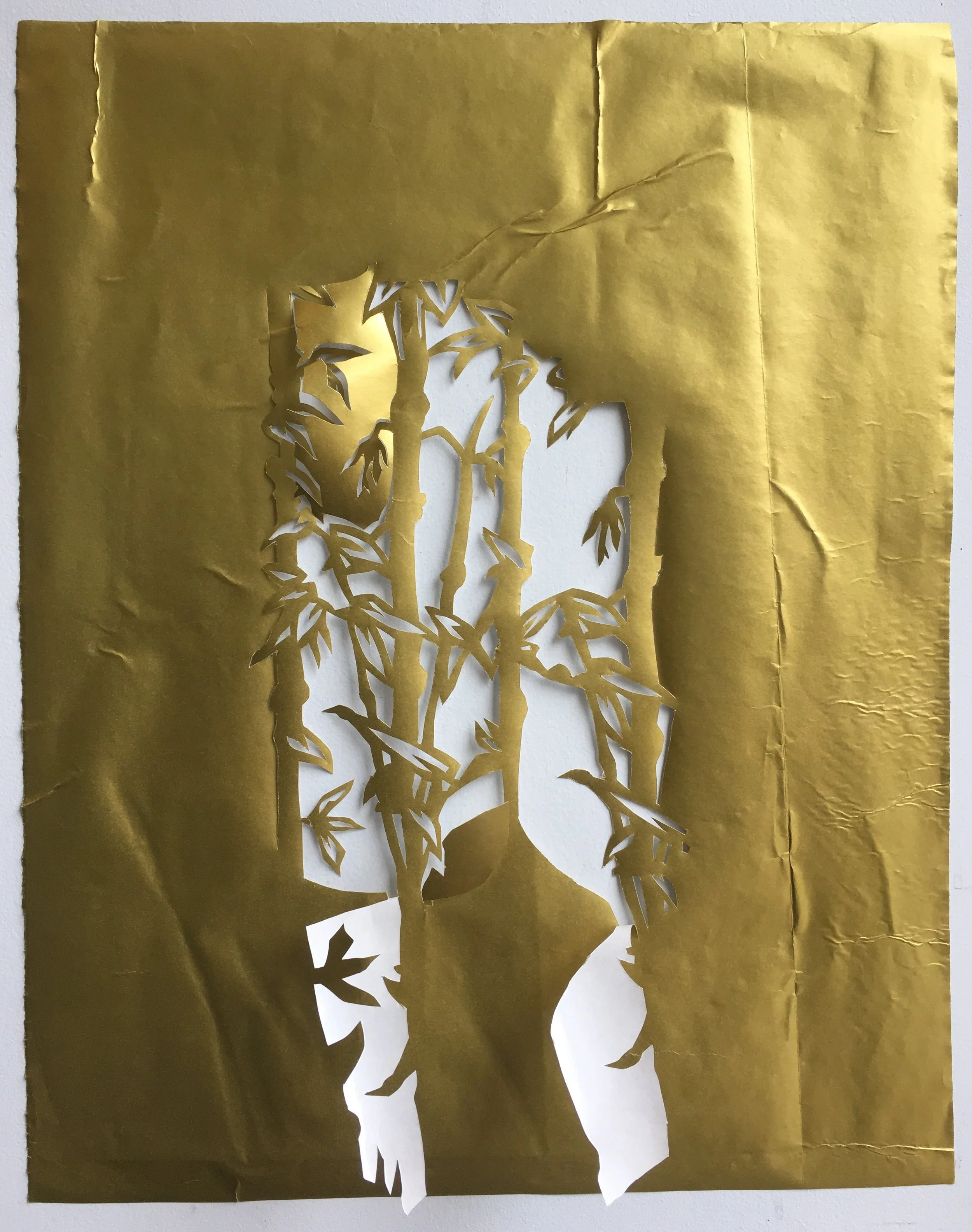

Nazlee Laila Mansur - Red Rickshaw (1994), Acrylic on canvas

Image description: The painting features a blue-skinned woman peering out between curtains. Her left hand pulls back the right half of the curtains, which are decorated with floral patterns and illustrations of colorful birds.

Twenty-six years is a very long time for any teacher to remember his or her student. However, there are some students that one never quite forgets—for various reasons. Iqra was like that. As I said, I kept meeting her sister over the years, but, in any case, I would not have forgotten either of them. Or Polash. Iqra should have done better in her exams—though, as it happened as it often does with young people, her heart got in the way. And, as I said, when it was time to take her Master’s examination, she was pregnant with her first child and had her baby four days after her viva.

Usually our students get recommendations from their tutorial teachers when they apply for jobs or for higher studies. However, in these twenty-six years, her tutorial teachers had either passed away or were too ill to give her a recommendation. I had not been Iqra’s tutorial teacher. I only knew her from how she performed in her viva—as head I was on her viva board for three years, two years of her Honours and one year of her Master’s. But I also got to know her from her involvement in our departmental seminars and plays. She volunteered in all our conferences and also acted in the plays that were staged by the department on various occasions.

I was both happy and sorry when she left Bangladesh with her husband, happy because they were together and sorry because we had lost someone with the potential of being a good academic.

From her CV I learn that she has worked and taught both in the UK and the US. Though her teaching experience has been limited to English, she did a second Master’s in Political Science. Her interest now is in studying the Quran. She would like to combine her literary interests with political theories in her doctoral studies in her new field of interest. I believe that, with her knowledge and experience, she will write an interesting dissertation, and provide a fresh perspective on the Quran. It is not a topic that she would have been encouraged to undertake here. (Comments on the Quran are apt to get one into serious trouble as the poet and writer Taslima Nasrin learned when she spoke a little too freely about the Quran. She has been living in exile since 1994. You would be more familiar with Salman Rushdie and the fatwa on his head for writing The Satanic Verses. Sadly, just when Rushdie thought that the fatwa had been forgotten, he was attacked brutally. He was fortunately not killed but has been left blind in one eye.) It is only in the free atmosphere of your prestigious institution that Iqra can undertake her studies in this area—though, I hope, she will be a little more circumspect and not get into serious trouble while writing her dissertation.

I believe that Iqra Islam has the language ability, the commitment and the courage to complete a PhD programme successfully. I strongly recommend her application. She will be a credit to any institution. I wish her best of luck in her doctoral studies.

Ismat Ara

Supernumerary Professor

Department of English

Dhaka University

Nazlee Laila Mansur - Woman and Billboard (2005), Acrylic on canvas

Image description: The painting features a purple-skinned woman wearing a flowing red shawl. She seems to be drifting out from a high window. Her arms are raised behind her head; she turns to look towards her right. Her window overlooks a city scene with apartment buildings and urban greenery under a dark-blue sky with a crescent moon. Towards the left of the painting, in the middle ground, a blue-skinned man stands on the roof of a building, leaning against the railing. He looks up at a billboard advertisement for Coca Cola.

Niaz Zaman is an academic, writer and translator from Bangladesh. Her short story collections are The Dance and Other Stories, Didima’s Necklace and Other Stories, The Maidens’ Club, and Selected Stories. Her novels include The Crooked Neem Tree, The Baromashi Tapes, and A Different Sita. She initiated the group translation of Kazi Nazrul Islam’s novel Bandhon Hara, published as Unfettered. She also translated Kazi Nazrul Islam’s novel Mrityukshudha as Love and Death in Krishnanagar and co-translated his Kuhelika as The Revolutionary. For her contribution to translation, she received the Bangla Academy Award for Translation in 2016.

*

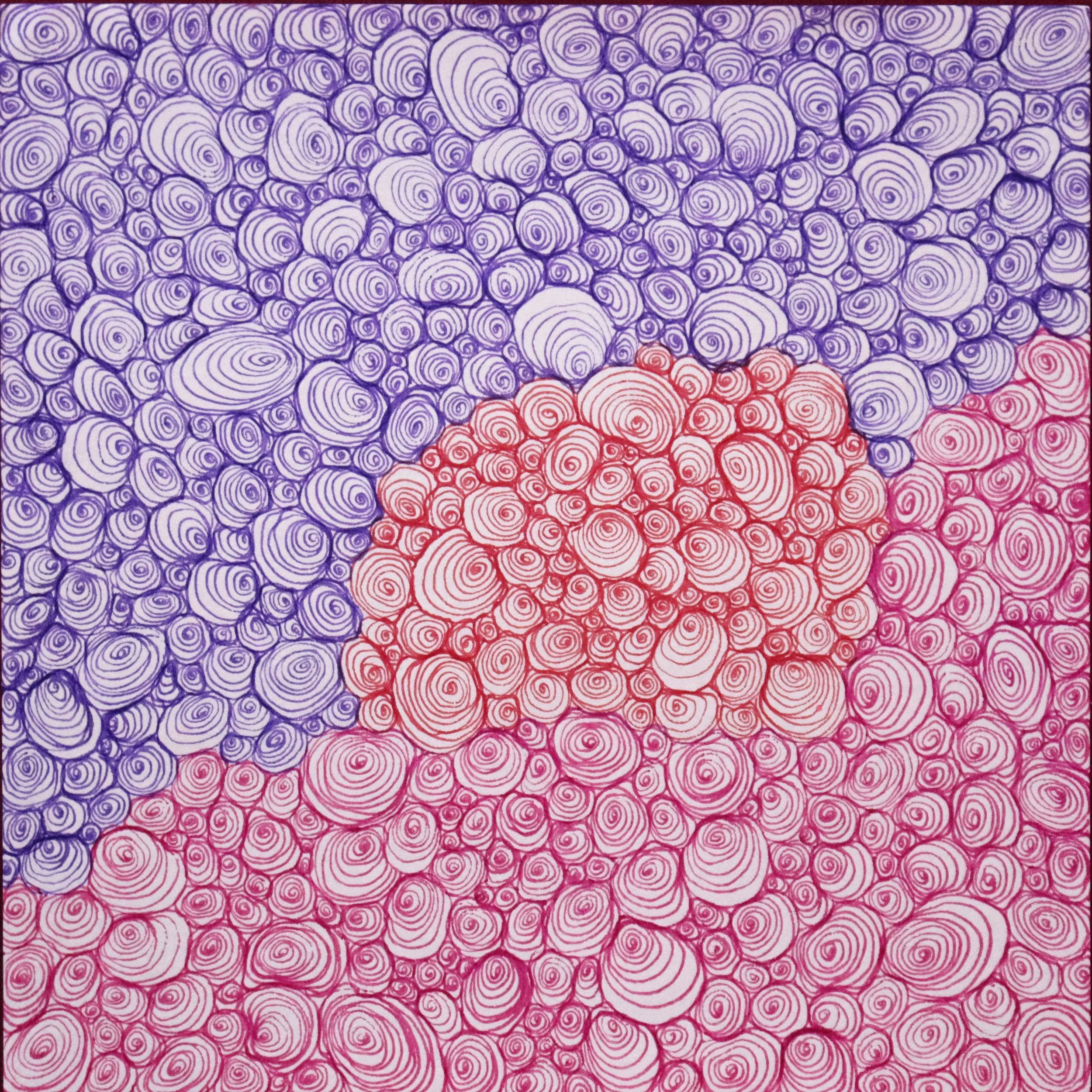

Artist Nazlee Laila Mansur (b. 1952) applies a subaltern art form from a non-appropriative stand for her unique visual storytelling. Her political stance manifests itself in vivid, saturated, and penetrating colors in her renditions of ordinary everyday events with everyday people. Nazlee’s palette is rooted in the present representing society’s inequities, oppression, rootlessness, and perhaps, dreams and longings. Her works are considered satirical by many. The artist earned a master's degree in fine arts from the University of Chittagong in 1974. She taught at the Government Art College in Chittagong. Her work has been exhibited in many countries.

If you’ve enjoyed reading this article, please consider making a donation. Your donation goes towards paying our contributors and a modest stipend to our editors. Singapore Unbound is powered by volunteers, and we depend on individual supporters. To maintain our independence, we do not seek or accept direct funding from any government.

‘But later… we didn’t talk about love. We talk about the land and its people.’ – a short story by Kaushik Ranjan Bora, translated from the Assamese by Aruni Kashyap.