The Final Flame: Extinction’s Edge

By Ian Mark Ganut

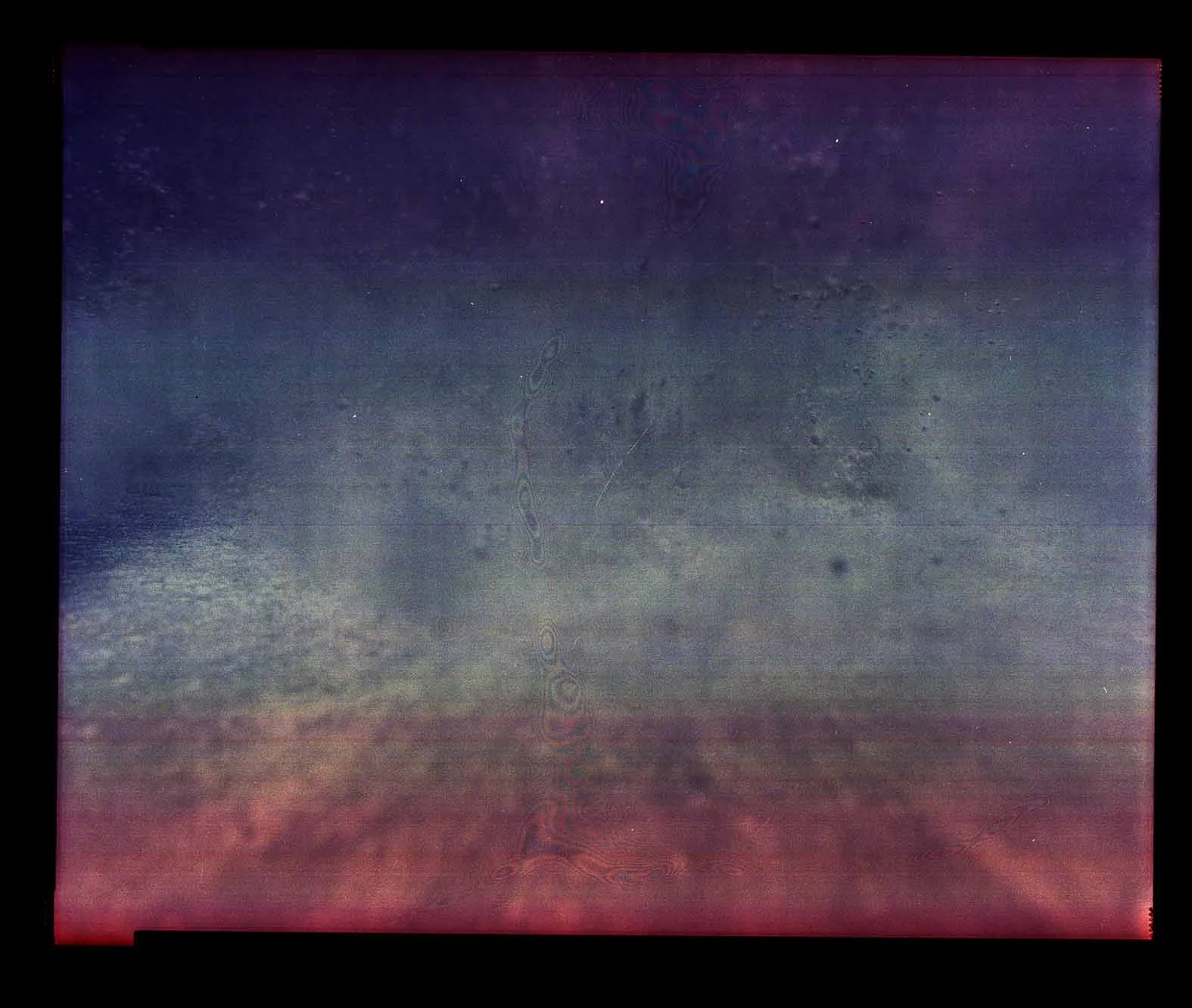

Zai Nomura, Ash to Ash, 2010. C-print, size variable.

Image description: A faint photographic image of an explosion is visible behind a transparent gradient (from top to bottom): violet, blue, green, orange, and red, within a black photographic film frame.

The air was thick with rust and the dry sting of ash, a reminder that the world above was still dying. Marlene's hands trembled as she touched the small locket around her neck, a ritual that had become as natural as breathing through her filtration mask. Inside, a curl of her father's gray hair lay pressed against a faded photo, the last Christmas before everything went wrong. She could still smell the pine needles from their contraband tree and could still hear her father's laugh as he handed her the tiny silver locket. "Something to keep your memories close," he said, not knowing how precious memories would soon become.

The weight of the oxygen pack dug into her shoulders, leaving familiar bruises that mapped her daily struggles. She tasted copper in her mouth, that same metallic tang that had filled the air the day they took him away. The corporate enforcers hadn't even waited for him to finish his morning coffee; the mug still sat on his workbench at home, ring-stained and dusty. Three years had passed, but the memory clung like dust to the corners of her mind, unshaken by time.

She remembered his hands most clearly. They were always stained with soil or smeared with engine grease, but somehow still gentle enough to braid her hair every morning. "Your mother used to love it when I did this," he would say, his voice catching on "used to." The cancer had taken Mom long before the corporations had taken Dad. The last time he had braided her hair was the morning they came for him. She hadn't worn braids since.

The device in her backpack felt alive, almost breathing against her spine. Dad's final project, not just circuitry and metal, but love forged into hope. He'd built it in their basement while teaching her algebra, explaining chemical bonds, between helping her with homework. "See, sweetheart? Everything connects. Just like us. The world's just forgotten how to listen to its own heartbeat."

Their basement had been her favorite place, a sanctuary of hope amid the dying world above. She would do her homework at the old wooden table while he worked, the scratch of her pencil mixing with the soft clicks and whirs of his tools. Sometimes he'd hum old songs, her mother's favorites, and for a moment, it felt like nothing had changed. But outside that basement, everything had changed.

The world around her was dying. Not in the dramatic way Holovids portrayed, but in quiet, heartbreaking ways that cut deeper than any corporate propaganda. A child's doll face-down in toxic mud, its plastic eyes staring blankly at a sky it would never see clear again. A wedding ring caught in the roots of a dead tree, its gold band tarnished by poisoned rain. A faded "Happy Birthday" banner fluttered from a collapsed school entrance. Little pieces of lives interrupted. Dreams abandoned mid-sentence.

She paused to adjust her pack, looking out over what had once been Central Park. The great lawn where she'd played as a child was now a crystallized wasteland, the grass turned to brittle shards that crunched beneath her boots. The old carousel stood silent, its painted horses frozen in an eternal race to nowhere, their gears rusted and their colors dulled by years of acid rain.

When the coughing started behind her, she didn't reach for her weapon. Maybe she should have, but something in the wet, ragged sound was too human to ignore. It reminded her of her mother's final days when the air had turned her lungs to glass.

She hesitated, fingers tightening on the filter. She’d counted every breath left in it, but that cough behind her was too familiar to ignore. "Here," she said, turning to offer her spare filter to the stranger hunched against a broken wall. "This one's still got a few hours left." She'd been saving it for emergencies, but the desperation in that cough told her this was exactly what she'd been saving it for.

His eyes met hers through his cracked visor, deep brown, lined with the kind of pain that ages a person beyond their years. Each breath wheezed through his failing filter, a sound she knew too well. "Save it," he managed between coughs. "Emma needed it more than I do."

The past tense knocked the wind from her lungs. "Emma?"

"My little girl." He straightened slightly, showing the small pink backpack he clutched to his chest like a lifeline. "She had a destination," he said softly. "HelioSpire Station."

Marlene's breath caught. That was her destination too—the place whispered about in scavenger circles, the last place rumored to still hum with power. If her father's device had any chance of making a difference, it had to be there. "She loved butterflies. Used to draw them everywhere, even though she'd never seen a real one. The filter failed while I was scavenging for medicine. By the time I got back..."

His voice cracked like thin ice, and he pressed his face against the backpack, shoulders shaking.

"I'm Marlene," she said softly, sitting beside him on a chunk of broken concrete. "And I think I have something Emma would have wanted to see grow." She reached into her pocket and pulled out a small packet of seeds, her father's last gift. "Wildflowers. Dad said they were the most stubborn things in nature. They'll grow anywhere, even in places we've ruined."

"Ezra," he offered, touching the seed packet with reverent fingers. "Emma would have loved that. She used to ask me what colors really looked like. What purple felt like on your tongue. What green sounded like in spring."

They talked as they worked their way toward HelioSpire Station, not about grand plans or technical specifications, but about the small things that made them human. His daughter's favorite bedtime story, The Secret Garden, as read from a tablet with half its screen cracked. The way her father hummed off-key while he worked, usually old Beatles songs he claimed were classics. The last real rainfall they remembered, before the water turned acidic enough to burn.

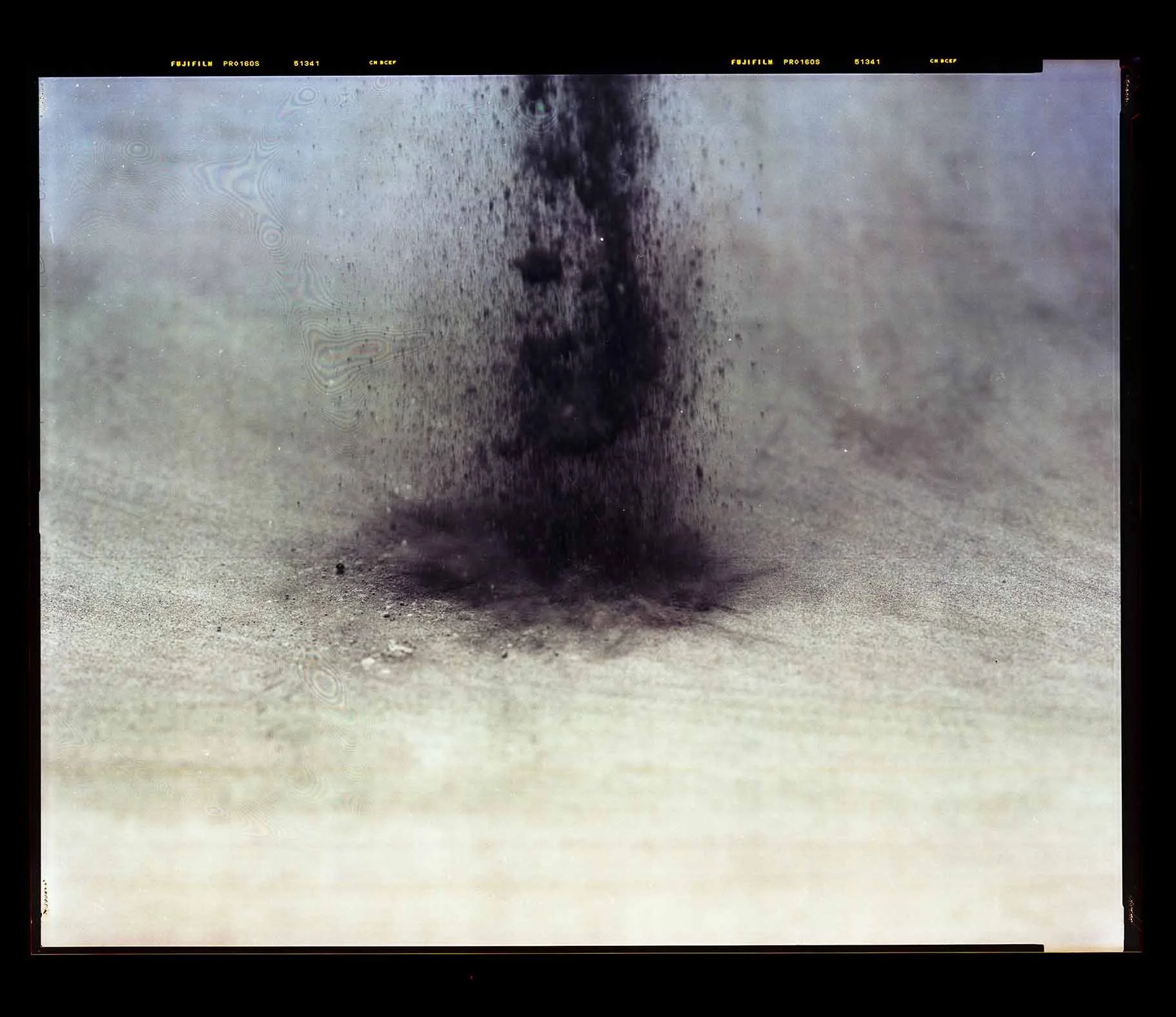

Zai Nomura, Ash to Ash, 2010. C-print, size variable.

Image description: A clear photographic image of an explosion of ink-black materials rises vertically against a pale ground within a black photographic film frame.

Ezra pulled Emma's backpack closer, unzipping it like he was opening a wound. Inside was her stuff, just kid stuff, wrinkled drawings, a hairbrush with strands still tangled in it, a half-eaten pack of crackers he couldn't bring himself to throw away. And the butterflies. God, the butterflies.

He held up a crumpled drawing, the colors bled where her tears had fallen. "Her hands shook so badly, but she wouldn't let the nurses help. Said it had to be from her." He touched a smudged corner. "She threw up right after. I told her we could make another, but she said it was perfect because it was real. Seven years old and she understood more than I ever did."

Marlene watched him smooth the butterfly's bent wing, his dirty fingers gentle, like he was touching his daughter's face. She thought about her dad's workshop, how she still couldn't go in there. His coffee mug was right where he left it, ring stain on the table getting darker every year.

"Dad used to burn his tongue every morning," she said, surprising herself. "Every single morning, too impatient to wait for his coffee to cool. Mom used to tease him about it. After she died, he'd still blow on it and say 'I know, I know', like she was there telling him to be careful."

The machine they'd built hummed between them, not like in stories, no magical moment, no dramatic lights. Just a broken sound, like both their hearts trying to beat again. Then, something shifted. A breeze moved without the stench of decay.

The first clean air came quietly. Felt wrong, almost. Like walking into your house after a funeral, when the silence hits harder than any noise could. Ezra breathed in and let out a sound, not quite a sob, but something raw and broken, like a crack splitting down the middle of a sealed-up heart.

"Emma used to ask what flowers smelled like," he said, voice raw. "I'd try to describe lilacs, but how do you explain purple to someone who only knew gray? I'd tell her, 'like happiness, baby,' and she'd laugh at me. Said I was being silly. But now..." He breathed in again, shaky. "Now I get it. They do smell like happiness. They smell like her."

A bird made a noise somewhere, not singing really, more like asking a question. Marlene remembered her dad pointing at empty trees, telling her where the nests used to be. They hadn’t noticed the soldier at first, just a lone figure near the edge of the clearing, motionless among the ash-flecked ruins. He wore the insignia of a corporate patrol unit, but his weapon was lowered, his posture hesitant, like he was listening for something long forgotten.

When he finally stepped forward and removed his helmet, snot and tears streaked his face. He looked like a kid. Just a scared kid with a gun, catching the scent of lilacs in clean air for the first time since he was small.

He dropped his weapon, the clatter loud in the silence. It didn’t sound like surrender. It sounded like remembering.

When the soldier took his helmet off, snot and tears mixed on his face, he looked like a kid. Just a scared kid with a gun, smelling his grandmother's garden for the first time since he was little. He dropped his weapon, the clatter loud in the clean air. It sounded like surrender. Like relief.

Ezra pulled out the last butterfly from Emma's bag. Blue crayon, wobbly lines, a corner missing where it got wet. "She made this one the night before… before…" He couldn't finish. Didn't need to. "Said it was for the new sky. Said it needed to be blue so it'd remind the real sky what color it's supposed to be." His hands were shaking so badly that he almost dropped it. "She didn't... she never..."

Marlene held him then, felt his tears soaking her shirt, felt her own falling too. They held each other like that, two broken people clutching paper butterflies and pieces of the dead, while around them the world started breathing again.

The real butterfly that came wasn't big or special. Kind of small actually, wings are more gray than blue. But when it landed on that little purple flower pushing through the concrete, Ezra made a noise like hope breaking him open.

"She would've named it," he whispered. "Would've given it a whole story. Probably something silly like Mr. Sparkles or..." He couldn't finish, just held Emma's backpack tighter, breathing in whatever was left of her smell.

Marlene reached out and brushed the dirt from Ezra’s shoulder, her touch gentle. A quiet gesture, like her father used to do. They let the paper butterflies go together. Not gracefully like in movies. Some got stuck in the dirt. Some tore. But some caught the wind, carrying Emma's crayon dreams into the clearing sky. Carrying a little girl's love story to the world, she never got to see healing.

Marlene's dad's hair floated away too, gray strands catching sunlight like they used to when he worked in his greenhouse. She thought she heard him then, that off-key humming, that burnt-tongue coffee laugh.

The world didn't heal pretty. It healed messy and slow, like grief, like love. Like a kid's crooked paper butterfly showing the sky how to be blue again.

Zai Nomura, Ash to Ash, 2010. C-print, size variable.

Image description: A clear photographic image of an explosion of dark materials is visible behind a blue-green gradient within a black frame of photographic film.

Ian Mark Ganut is a Filipino speculative fiction writer whose work explores themes of memory, survival, and the quiet resilience of love. He holds a background in education and agri-fishery arts, which often weaves into his stories of post-collapse worlds and fragile hope.

*

Zai Nomura (b.1979) was born and raised in Kobe City, Japan and has been living and working between Kobe and New York since 2020. He received his his MFA from Goldsmiths, University of London, and his PhD in Fine Arts from Musashino University, Tokyo. Both the death of a close family member with a disability and the 1995 Kobe earthquake, which he experienced as a young person, led Nomura to question the permanence of matter and existence, ultimately informing his creative practice. Recent exhibitions include the 13th Seoul Mediacity Biennale held at SeMA Seoul Museum of Art. He participated in the ISCP artist-in-residency program in New York, and became a fellow at Yaddo in 2023. More info: https://www.nomurazai.com and https://www.instagram.com/zai_nomura

In a short story by Yu Xi, translated by Ng Zheng Wei, a gnawing hunger consumes everything.