Island End

By Kevin Martens Wong

Rudy Atjeh - Menarilah! (2021), variable dimensions, Parchment (3 pieces)

Image description: The image shows a triptych of paper-stencil sculptures made from golden-colored parchment against a bright-red wall. The top left figure looks like a creature with semi-opaque clouds for its body; a pair of eighth music notes for its eyes; an arm with an extended index finger for its tail; Pegasus wings; and hooved legs. The top right figure consists of another cluster of clouds, from which a pair of arms emerge, holding a bunch of flowers against the backdrop of a square. The bottom figure features a scene with mountains and a cave with geometric, web-like stencils. The bottom of the scene shows the ripples of a pond, overlapping with the letters of the word “happy.” A separate cutout of a branch with leaves rests on top of the pond, intertwining with the letters. At the top left of the sculpture, a woman-shaped cloud of smoke emerges from one of the mountains.

203 years, 4 months and 4 days after her sudden, uncertain, and completely inexplicable disappearance, Mama Ujong has never looked more dangerously dazzling as she does when I walk up to greet her in the morning for the 74,269th time, beaming like the sun trying a little too hard to compete with something far more unearthly. I say so, and she beams even more. Beaming is what she does best. She is who she is, after all.

“Bong pamiang,” she says, probably by way of an afterthought. Good morning. Of course I still speak the mother language to her. She likes it. (You know how I can tell? Guess how I can tell. My eyes are blinded.)

“Neches,” I say again. It means nice in patois, borrowed from the Dutch starting from the 1650s. “It means nice, Mama.”

“You flatter me,” she says, again a little too daintily. “Neches is for girls. For fila-fila. For furiyada.”

“Explain to me why you do not fit either of those two categories, Mama.” It’s a simple room, as these kinds of rooms go; a bed, furniture set, large window, fan, aircon. I pour the tea carefully, ensuring that it is nearly brim-full but not quite. The last time I didn’t quite make the mark, she electrocuted me. It was a difficult day.

Few people quite truly titter anymore – the newer generations honestly think of tits first and laughing later, especially where Mama Ujong is from – but Mama is still absolutely fantastic at it, a grade-A titterer to put many politicians, again from where she is from, to shame. Tittering is an art that must never be allowed to die. I note that thought down in my notebook. Something for later.

“What are you writing? Ki bos ta skribeh?”

“Oh, Mama. Namas di bos sa buniteza.” Only of your beauty, with emphasis on the beau. I’m not even sure if people say namas anymore. Who can tell, really? It’s been more than a hundred years since anyone has even spoken like Mama. We could speak Malay, of course, but I’ve noticed she’s been partial to patois since the revival, and who can blame her? It’s difficult to always be on your most brilliant and radiant behaviour, and the Linggu Mai has always allowed for one to express much more than one could in polite company. Not that she has much company.

“Tell me, pochi –” Mama Ujong swivels. Hair is swept. Eyebrows are curled. “– what news of the colony?”

Pochi means teapot in patois. Close enough, I guess – at least she recognises the object. “The Settlement continues to grow in modern fashion, Mama.”

Mama tsks. Her body vibrates, and for a few, lustrous shivers, she looks completely different, her hair now climbing into ornate, bejewelled heaven, cheekbones severe and prostrate. Lips press out a single, simple word that has also come to define her homeland.

“Aiyoh.”

She shivers and switches back into the Portuguese, body once more changing, teeth flashing again. Sharp, mincing sweetness. “Why ah.”

“You ask me, I ask you lor.” I do my best to get the intonation right; the moment hangs in the air, suspended, as if Mama Ujong is confused. But she gets me, and smacks my arm daintily. Shivering again, changing again. I know this one.

“Sayang,” she says, as if I am the most tedious and ill-disciplined teapot in the world. “I want to know.”

“I really don’t know,” I say, in Malay. I have always loved how tak tahu sounds, the precision, the focus, the slight frustration it can so easily convey in situations like this one. “I’m not one of them. I only watch them for you.”

“You call this watching?” Emphasis on last syllable. A snort of sparkling derision. “Kasita would also have some questions.”

“I’m sure she would.” Please don’t ask about Kasita. Kasita… I mean. We don’t talk about Kasita, and I want to write that down too, but that ridiculous song is all over the collective unconscious, not just in Mama’s homeland, and when you live as long as this teapot, you want to be very careful about the earworms you allow into your heart. If I have one. Kasita… she’s not dead. I’m not sure what you’d call it. Suspended? Frozen? Nope, DO NOT write that down either, Pochi.

Mama Ujong sighs. “You haven’t brought me any news from her in a while either, Pochi.” She strides, as she always does, to the window that overlooks the Great Ocean, the one that we stridently advise guests to try to avoid looking out of, and which Mama Ujong, unsurprisingly, spends most of her time stridently looking out of, like now. “Nothing from her. Nothing from Kasita.” She spreads her fingers. “Nor from Raden, or GY, or Hanu, or anyone. It’s been days.”

Well, technically decades, but if that’s your experience of time, who am I to challenge it? “Yes, Mama.” Of course, we also force that very experience of time on her, so…

Mama Ujong sighs again. “A pretty poor parrot you are, Pochi.”

I am about to make a note of the stunningly quotidian alliteration when I notice what she has said in full detail. And… she’s not quite beaming anymore.

“Mama!” I gasp.

Mama Ujong looks at me quizzically. “Seng, sayang? Ki kauzu?”

“No kauzu,” I say, adjusting myself as best I can. “No kauzu at all. Just…you called me a parrot.”

Bemusement. “Of course I called you a parrot, Pochi.”

“Again!” I gasp, and try to suck it in, far too slowly. Mama is getting the electrocution face. Koitadu, ah, Pochi. “… I… I mean… ”

Mama looks at me with less veiled contempt now, which is a relief, I suppose. “You are a parrot, are you not?”

I gulp. “A green one. Yes, Mama.” How has this happened? The Jubilee will have to be alerted! “Mama… if I might ask, are you okay?” Is it the window? “Do you want to come away from the window?”

She smiles. Again, the contempt is so scantily clad that it might as well be tittering, as I once read in an essay generated by a thirteen-year-old from her homeland. Okay, it was the window. “Mama… ” I say, fumbling with the empty teacup. “… how much do you remember?”

She doesn’t answer my question, but turns toward the window. I knew the window was bad news. We really should learn more from Mama Ujong’s homeland. They know how to do windows properly. Especially in their prisons. No one said this was a prison, of course. I want to slap myself – by the Unus Mundus, I almost said that out loud.

“Where is Kasita?” Mama Ujong says, finally.

“Mama… eli… ” Even a critically-endangered language does not quite have the word I’m looking for. Yes, it’s a little Orientalist. After everything I’ve read, heard and observed about race, culture and ethnicity from the dreams in Mama Ujong’s collective, this is already saying something. “Eli… nteh naki.” She’s not here. Best way I can put it.

“The Panji?” Mama demands.

“Pun nteh naki.” That one definitely. “They’re not here anymore either.”

“Adamastor?”

“No, Mama.”

“Sang Kanchil?”

“Definitely not, Mama.” You always ask about Sang Kanchil, and I always tell you the same thing. Mama Ujong is shivering. Switching. Everything, everywhere, all at once. I watched that too and it was a little like this, though I’m not sure which one was more diverse, especially with the radiation coming off of Mama Ujong.

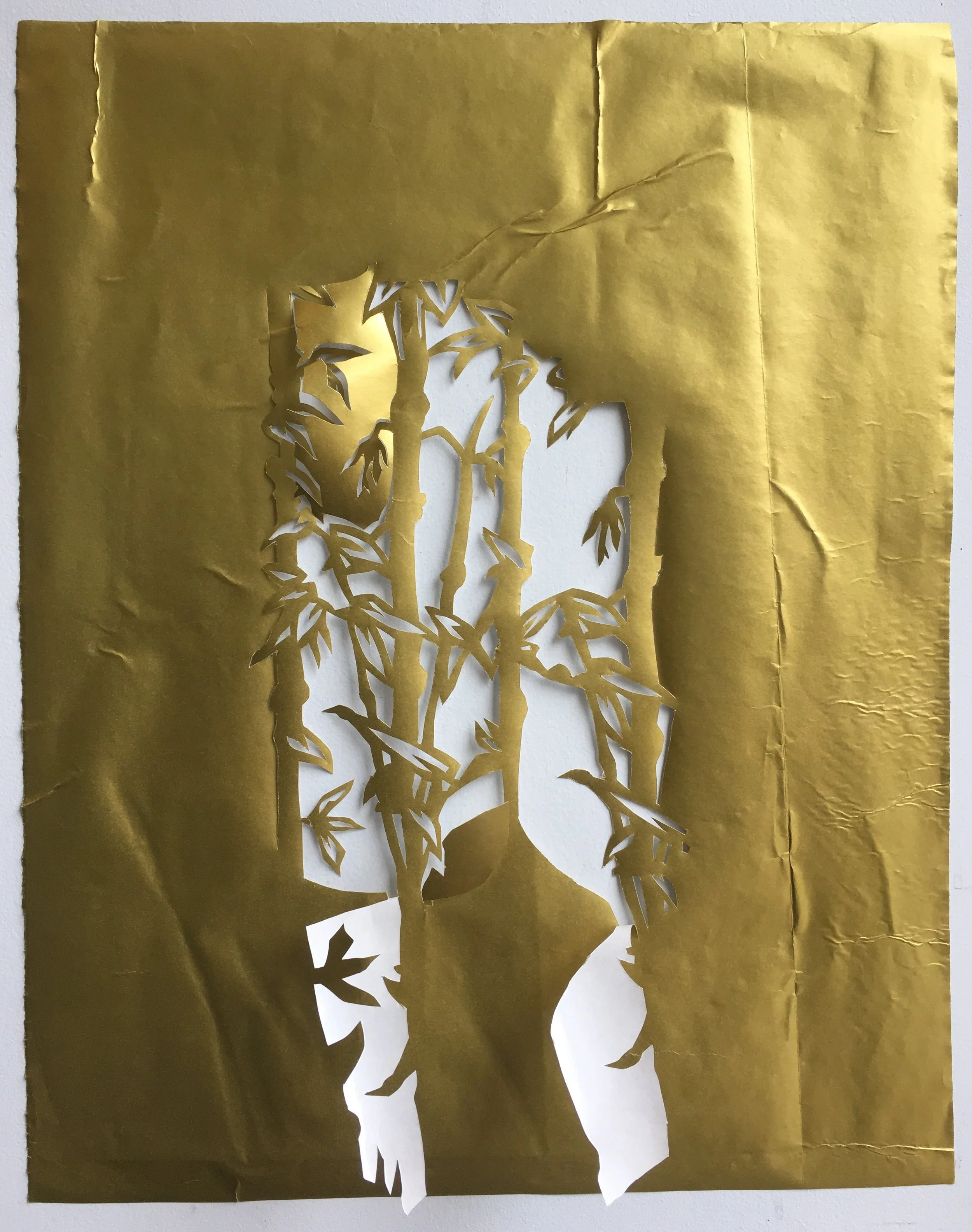

Rudy Atjeh - Welcome To The Jungle (2012), Installation, variable dimensions, handcutting on paper, sound ambience by Sodadosa

Image description: The image shows a large-scale, hand-cut, paper installation in a dim room. In the left foreground, a white, paper-sculpted hand is lit by a purple spotlight. The hand holds its palm open; its five fingers point straight upwards. The hand is covered with cutouts of astrological symbols and English words. Cutouts of naturalistic palm lines are annotated with "heart line," "head line," "life line," and other phrases related to palm reading. Where its wrist should be, the hand becomes a twisting, serpentine body. On the first section of this body are the words "No matter what your palm says your destiny is in your hands." Slightly behind the hand sculpture, a pile of white and black, paper strings is lit by colorful lights. In the background, numerous paper cutouts are suspended in the air. On the far left, a black cutout of a cobra spells out the word "Pray" with its elongated body. The cobra encircles a pair of hands. In the center, another black cobra spells out "gold." Slightly above it is a black bird of prey mid-flight. To its right, a white bird of prey spreads its wings and holds a white cobra in its claws; the body of the cobra spells out "every time." To the far right, a black tiger is depicted mid-roar. Its tail spells out "Play" above its body. White, paper stars hang from the ceiling; each has the cutout of a letter or number.

“Is – there – anyone?” Mama says, and I’m not sure what she’s speaking anymore, though I can still understand. “Anyone?” She looks at the window again, then back at me, eyes aglaze, aglaze being a word that I just coined to try and explain what it is like when an immortal representation of the personal collective unconscious of a significant group of human beings is angry and reflecting the light of the Great Ocean through her eyes is angry with you. “What about Singa? TPK? Bela Infanta? Can I talk to the fucking Merlion?”

“Mama,” I say, and I’m a little exasperated too. I thought we’d been through this. And she called me a parrot this time! I thought we’d been through this. “You know what happened the last time we tried having you talk to the Merlion.” Let’s just say other things came out besides water lah hor. “Uncle PK’s not here. And Singa – ”

“I want to talk to Singa.” Mama’s voice is sharp and crackling.

“Mama, Singa –”

“No, Pochi.”

“Mama –”

“I want to talk to Singa, and I want to talk to Singa rig –”

“MAMA.”

I’m ablaze, and when ablaze meets aglaze, only one of those words is going to stand the test of time, probability, reality, and everything else that this green parrot teapot construct is going to throw at you. “MAMA.” I’m thundering. She falls back into herself, collapsing. “Singa doesn’t recognise you, Mama.” You’re not supposed to tell them that, Pochi. I don’t care, Jubilee. “Uncle PK doesn’t recognise you. The Merlion won’t even look at you. I’m sorry. This is the Pedredu sa Kelong, Mama, not Valhalla or Olympus.” The Floating Home of the Lost, in patois. The Great Ocean’s Best Rest for Forgotten Gods, Deities, Demons, Horrors, Anthropomorphic Manifestations and Anything Else from the Collective Unconscious That Does Not Know Why or Has Forgotten Why It Exists, but Continues To. It’s printed on the stationery (in very small letters, but still), bedsheets, my apron. Mama should know this. We talked about this, and it was embedded at a deep level, before the sleep, before the forgetting. She should know I’m not a god or a resident myself; I know why I exist, though I don’t know how I came to be. That’s the Jubilee’s problem, and whoever the Jubilee reports to. I’m just the messenger. Some shaman or fitiseru’s old daimon, the reward for all the magic they did over there behind the curtains in the real world. The ‘pomp. The sibidor, if you prefer Kristang, or the skrabu, if you prefer the demeaning Kristang.

Yeah, I don’t remember who I used to be either. And not for want of asking the Jubilee, over and over again. But I’m comfortable with it. I’ve made my peace with it. But there she’s weeping, and sputtering, and we said, don’t look at the window, don’t try to remember, just be here, here is nice, here is Pochi with your afternoon tea and some nice clothes for you, before colonialism corrupted what the idea of tea and nice clothes for you even were. Just enjoy Pochi’s company. I always get the difficult ones – goddamn Ananke, back in the second century, she took so freaking long to just fuck the fuck off. Okay, I had a good time with Tlappapalo in the 1600s, but she was an exception. Urizen. I’ll never forget Urizen. And now I have Mama Ujong.

“I want to talk to Singa.”

“Mama, it’s not possible.”

“But someone remembers me!” she wails, as if hearing my thoughts. “Someone must.”

“Yes. Otherwise you would not exist.”

“But they remember Singa. Why am I here when Singa is out there?”

Because Singa is an emblematic mascot of a value that 98.74% of them actually do not have at all inside their heartless, soulless bodies, and is so desperately needed that it is a joke that they haven’t had a temple built to them yet. “I remember you,” I say, trying to be soothing.

“I don’t care about you, you fucking bird!” she screams.

Oh, well, I guess we know who else needs Singa in their lives, right, Mama? She still did call me a bird. At least she gets it this time. “I want a human to remember me!”

“And humans do remember you,” I say, and I know what comes next. Every 4,026 days there has to be one day just like this one. “But Mama… this is how they remember you.”

Mama Ujong is inconsolable. At least there’s no lightning, or caustic river of blood-water or ghoulish apparitions screaming LARANGAN this time.

I hold her.

I mean, I’ve held her for 74,269 days, and probably for a little more. And I would need it if I were in her shoes. Her home island is stubborn, cruel and stupid, and that is a difficult combination indeed to manage.

“I am the land,” Mama Ujong whispers. “Surely they must remember the land.”

She’s calming down now. The fucking bird will take care of everything. Don’t you worry. I’m a good fucking teapot, Mama.

“Koitadu,” I say. It’s patois for a complex emotion involving pity, apology, remembrance, consolation and loneliness. Sometimes, I wish I had emotions, so I could experience the full range of what it is like to know a word that expresses an emotion that few people know they are carrying around – and which everyone, every human, at least, is literally carrying around.

I look out the window because it’s okay for me to do so; I won’t die. All humans and their creations will, though, Pochi. The Jubilee had been clear, and the Jubilee had been right. As always.

“There… used to be jasmine,” says Mama Ujong. “A spring. A big hill. People were calm. People were in life. In bloom.”

She tries to look out the window, but I step firmly between them.

“I was called Golden once, even,” she says. She’s not really there. But something strikes me. “Keris. Or Khryse.”

The name strikes. Something flashes across my notebook, but it is in my mind.

“I know you,” says Mama Ujong. You wrote my name down once. There it is again. Χρυσῆ Χερσόνησος.

Not my job. Not my memory anymore.

I rub my eyes and sigh, taking her hands.

People were connected to the Great Ocean, and then they weren’t. I’m sorry, Mama.

“Koitadu,” I say again, and this time, I use all my dazzle, all my serenity, all of my empty heart. “Nang lembrah, Mama.” Don’t remember. Listen to my voice. “Ubih yo sa song. Bebeh yo sa chai.”

“Chai…” she says, reaching for the teacup. I pour her a little more, but she won’t make it. The sleep will overtake her soon. Hopefully her memories, too. Again. But it is my job.

“Where did all of it go?” she murmurs.

“It’s still there,” I say. And this is true. “The land. The gardens. The jasmine.” Okay, maybe the first two. Okay, maybe the first one. Well, the second too, though… I wouldn’t count it as original.

“Goddess of the gardens,” she says, and I wish I hadn’t said that. In some other world, she really probably was Deus Jarding. But no matter. The sleep is rolling over her now.

“You are my goddess, Mama. Yo sa deus.”

“You need a god, meh?” she says, through slurring syllables.

Actually. That is a good question. I want to note it down for later. Humans need gods. Us…

“You… mutu bong… sikapong…”

Rudy Atjeh - Symphony For The Almighties (2016), Installation, variable dimensions, handcutting on paper, video

Image description: The image shows a white, hand-cut, paper installation of animals and words suspended against a white background. In the center are the words "holy power" in large, cursive letters, spelled out by the twisting body of a serpent. The serpent sticks out its tongue, which spells out the word "god." The serpent's tail is held in the claws of two birds of prey. Directly above them, a third bird, the only figure in black, is depicted mid-flight. The serpent is flanked by two tigers facing it. Both tigers have open mouths and human arms. The tiger on the left holds its palms together as if in prayer. Above its body, its elongated tail spells out the word "Pray." In its background are translucent mountain scenes. The tiger on the right holds a cylindrical instrument with two handles. Its tail spells out the word "Play." In its background are translucent hills and trees. Ornamental paper strings drape across the entire installation. Paper stars hang from the ceiling; each has a cutout of a letter or number.

Mama Ujong, that actually sounds like Kristang. “Psychopomp, Mama.” We actually made it to psychopomp. The Jubilee and all of humanity should take this as irrefutable proof that prisons should be built without any windows at all. Look at all the hope it lets in. “One more song, Mama. Ngua kantiga mas.” This still exists in their world, after all, though I can probably count on my fingers the number of them who still remember it on Ujong.

“Am I dying, Pochi?”

“Ngka, Mama.” I shake my head. “Just sleeping.” By Unus Mundus, you can even breathe life into new patois words. Not dead.

“Will I die, Pochi?”

I shake my head. “After the song, Mama.”

She closes her eyes. “Okay. Ki sorti di kantiga?” What kind of song?

I hesitate, but only for a moment – I’m still thinking about the do ‘pomps need gods? thing. I need to write it down. But the moment calls for me.

“Ah, isti yo sa kantiga, Mama. Na nus sa linggu.”

This is my song. In our language.

Pasturinyu bedri

Na ramu teng dos-dos

Nadi yo mureh lonzi

Sertu mureh pertu bos

Little green parrot

On the branch, just us two

I am sure I will not die far away

For sure, I will die close to you

THE END

“Pochi?”

Mama – why aren’t you sleeping? I sang to you already!

“I couldn’t stop thinking, Pochi – about what you said.

Mama, I say a lot of things, Mama.

“Why after the song, Pochi? Kifoi?”

Mama… well… I guess… how do I say this?

“Am I dead, Pochi?”

How do you know? How do any of us know?

In a flash, she is up again. Teapot and saucers clatter to the floor, and I am clattered to the door by a fist, multifarious and shifting faster than the eye can see: now, a fist; now, a TikTok about Chinese privilege; now, a bus workers’ riot.

“You fucker, Pochi, you,” says Mama Ujong. Her breath is all over me; rosewood, and sandalwood, and camphor, and sea-cucumber.

“M – mama –”

“You know,” she snarls, electricity crackling around my throat, her hand – her police line – her illegal demonstration protesting the liquor control zone gripped around it, “that I hate being reminded of my mortality.”

“But –”

“You know,” she adds, the fury of two thousand, four hundred and sixty-seven spoilt votes in the Southern Islands glistening in her eyes, “that I hate that fucking song.”

“I – Mama –”

“And you KNOW,” she says, “that that is not what you call an old Singaporean woman.”

She explodes. The door explodes. Everything explodes. My body is charged, set alight, burned, reframed, censored, disintegrated; this is worse than the electrocution. It was the void; it was the song. Maybe it was the Kristang. I don’t know. I am lying in the hall, and she is out. She has never gotten out before. I am trying to move. I cannot. She looms over me.

“You better fucking call me Auntie,” says Mama Ujong. “You understand, hor?”

“Hor,” I repeat mindlessly, profusely – what else is there to say – and then regret it so, so much when her eyes flash again.

“Fucking say my name, parrot, and don’t you dare call me a whore.”

“Yes, auntie,” I say feebly, struggling to remember it. But it is there.

“Say it,” she says in Kristang, in Telugu, in Slitar, in the languages that time forgot. The Jubilee will kill me. The Jubilee will fucking kill me. But Mama Ujong – no, not Mama Ujong – she has killed me. She has remembered. She always remembered. She was waiting. Waiting for this.

“Yes. Yes. Tuanku.”

“SAY MY NAME,” she commands.

“Yes, Parameswari.”

She is known by many names. She always was. I speak in tongues, like she does. Parameswari. Permaisuri. It doesn’t matter. As long as it is not the Jubilee’s name for her. Names do so much, you know? Like calling me parrot. Or pochi. I know this. I knew all this. And she knows I know.

“Show me this, this Jubilee,” she says.

“… Mam – Auntie – my most beauteous queen,” I say, as she disintegrates part of me again, and I apologise for my errors, for my excesses, for the tea, for everything – I know who she is. She knows who I am. How do I explain this? How do I even articulate this? No one can just see the Jubilee. “Most munificent. The Jubilee –”

“– is dead.”

She gasps. I gasp. In the dimly-lit corridor he comes striding, dragging the body of one of my compatriots behind him, barely still constellated, as broken and electrocuted as I am. For the first time, I can make out other sounds, too. Scuffling. Things breaking, much more important things than the teacup and the saucer. Many screams.

“PK,” says Permaisuri Ujong, half wonderingly, grasping him, touching his arms as if he is no more an apparition than I am. “PK.” His form is gone, too; I wonder if my compatriot, the broken, Indigo Parrot lying in a trail of dust and aether behind him, has also learned that calling him Uncle was never quite the best idea.

“Tuanku,” he says, kissing her hand. “The Merlion and I, and the others… it has been so long.”

Rudy Atjeh - The Next Unknown/Follower Generation (2016), Installation, variable dimensions, handcutting on paper, video

Image description: The image shows a hand-cut, paper sculpture suspended against a black-and-white image of crashing waves. The sculpture, of an elaborate latticework structure, is in the form of a human head. Ears and hair are projected onto it in yellow, blue, and green lights. The lights cast shadows of the latticework onto itself, resulting in an intricate web of overlapping lines and shadows. Where the right eye should be, there is a cutout of the yin-yang symbol. Where the left eye should be, there is a triple-bar symbol. The head wears a lattice crown featuring cutouts of various religious symbols. The Crescent and Star are in the middle; below it is the Star of David; above it is the Om; on its left is the cross; and on its right is the wheel cross.

She turns his deference into a warm, enrapturing embrace, radiating joy, strength, hope, even as something else slams into the wall behind us, and one of the other Parrots screams, far down the corridor. Mama is gone. Mama is gone. The Jubilee will variegate me for this, I say. But… I look at the indigo parrot. The Jubilee is gone.

“We are released, Tuanku,” says PK, echoing my words. “The Jubilee is gone.”

“All of us,” says Permaisuri Ujong, half as a question, and half in awe. PK nods. She gasps, her aura bobbing in the air, as the complex shudders again. “Is it not chaos?”

PK smiles, a smile which fills me with terror, and fear, and… serenity, for some reason. “It is everything that you would wish for, Tuanku. Everything that all of us has wished for.”

Permaisuri Ujong turns to me and the indigo parrot. I want to scramble back in terror, but she lingers; her hand brushes my charred, dismantled face, my angry, seared feathers.

“Be who you once were,” she whispers, “before they came.”

“Before… who came?” I start to mumble, but she has already begun to sing.

Pasturinyu bedri

Na dianti di morti teng dos-dos

Nadi yo kureh lonzi

Sertu bibeh juntah kung bos

Little green parrot

In front of death, just us two

I am sure I will not run away

For sure, I will live alongside you

I feel the change come over me; the words are not in English, but in Gujarati, in Teochew, in Banjar, in Singapore Sign Language, a dazzling array of signs and symbols, words and worlds, re-encoding, deconstructing, decolonising me. Neches, I think to myself; borrowed from the Dutch. What else was borrowed? I let it go. I leave it behind. And she brings me back to myself; to my mind, yo sa mulera; my body, yo sa korpu; my heart, yo sa korsang; and finally, my soul, yo sa saiki.

203 years, 4 months and 4 days after my sudden, uncertain, and completely inexplicable disappearance, and Permaisuri Ujong has never looked more dangerously dazzling as she does when she wakes me up, at last, to greet her in the morning that the Jubilee died, for the very first time, beaming like the sun that knows it will never have to compete with anything that is of this earth.

Pasturinyu di jarding, she says, naming me, calling me, chomah kung yo, by my own name, and I know it. I was always a bird of paradise. I say so, and she beams even more. Beaming is what she does best. She is who she is, after all.

Kevin Martens Wong is a gay, non-binary Kristang / Portuguese-Eurasian speculative fiction writer, independent scholar, and linguist. He is the editor of Kadamundu: The Spice Road Review (kadamundu.com) and leads the internationally-recognised grassroots movement to revitalise the critically-endangered Kristang language in Singapore, Kodrah Kristang; he was also the 2017 recipient of both the President of Singapore's Volunteer and Philanthropy Award (Individual–Youth) and the Lee Hsien Loong Award for Outstanding All-Round Achievement. His first novel, Altered Straits, was longlisted for the 2015 Epigram Books Fiction Prize, and his work has also appeared in Transect Magazine, Entitled Magazine, and at the Light to Night Festival. He currently runs his own freelance coaching and consulting initiative, Merlionsman (merlionsman.com).

If you’ve enjoyed reading this article, please consider making a donation. Your donation goes towards paying our contributors and a modest stipend to our editors. Singapore Unbound is powered by volunteers, and we depend on individual supporters. To maintain our independence, we do not seek or accept direct funding from any government.

‘But later… we didn’t talk about love. We talk about the land and its people.’ – a short story by Kaushik Ranjan Bora, translated from the Assamese by Aruni Kashyap.