#YISHREADS February 2023

By Ng Yi-Sheng / @yishkabob

It’s Black History Month! But, as N. K. Jemisin asked in her essay: “How Long ‘til Black Future Month?” [1]

How Eurocentric (or, for that matter, how Sinocentric or Asiacentric) are our collective imaginations when we share fantastical and sci-fi visions of alternate realities? Even if we do include Black characters—as is becoming more common, in the age of Bridgerton and The Falcon and the Winter Soldier—are they mere tokens? And how much do we actually centre the continent of Africa, as Nnedi Okorafor demands in “Africanfuturism Defined”? [2]

Anyhow, for this month’s column, I’m sharing works of speculative fiction by the global Black diaspora, from Africa, Europe and the Americas—though some of these writers have associations with Singapore: Nii Ayikwei Parkes is in regular dialogue with many of our Anglophone poets, and Helen Oyeyemi spent a bunch of 2018 as Writer-in-Residence at Nanyang Technological University.

(Oh, and if you want to find out about actual Black history in this country, check out my performance lecture Ayer Hitam: A Black History of Singapore. The script’s published in my collection Black Waters, Pink Sands.)

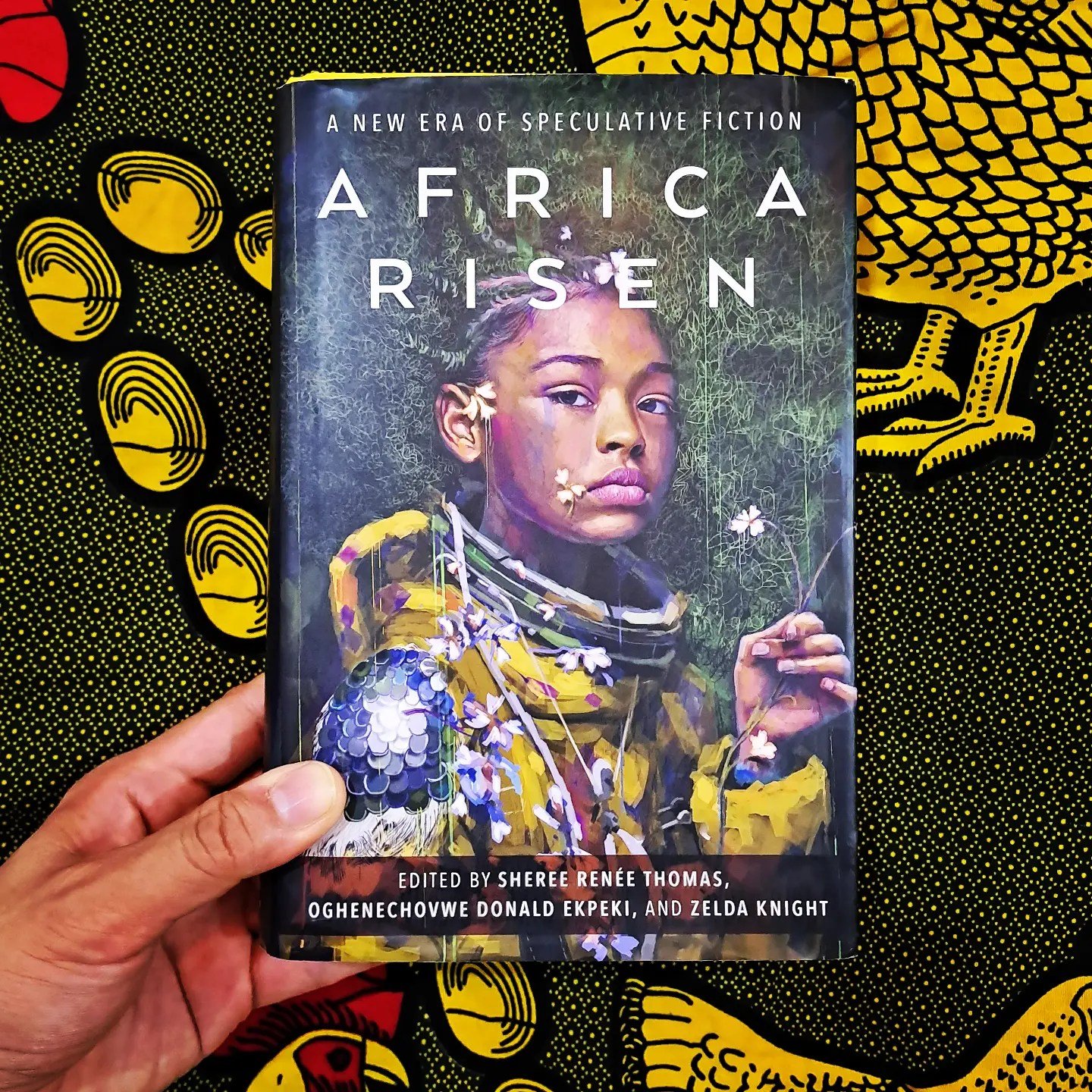

Africa Risen: A New Era of Speculative Fiction, eds. Sheree Renée Thomas, Oghenechovwe Donald Ekpeki and Zelda Knight

Tordotcom, 2022

There's been loads of buzz about this anthology, which includes thirty-two short stories from across Africa and the diaspora, almost all by names still unfamiliar to me. Lots of great stuff in here, especially from the realms of fantasy/horror.

I love the absurdity of a travelling Nigerian salesman cursed by the fact that he's lost a copy of Things Fall Apart in Tobi Ogundiran's "The Lady of the Yellow-Painted Library"; the fascinating image of a secret collective of Black witches, each representing the cardinal directions of the regions of the USA, gathering in 1963 to protect MLK as he speaks his I Have a Dream speech in WC Dunlap's "March Magic"; a horrifying tale of colonial-era patriarchy in the form of a Black doctor who bows and scrapes to white men and terrorises all natural and supernatural kin in Chinelo Onwalu's "The Taloned Beast"; a hiphop artist practising dark magic to trap women in his songs in Tlotlo Tsamaase's stylistically daring and dazzling "Peeling Time (Deluxe Edition)".

And yet when it comes to sci-fi, which is clearly dear to the editors' hearts (the book opens and closes with such tales), there's a strange absence of the kind of optimism you'd expect from the title. Black folks may have tech and agency, but they're still suffering through climate disasters in Tananarive Due's "Ghost Ship" and Russell Nichols' "Mami Waterworks"; they're threatened by war in Wole Talabi's "A Dream of Electric Mothers" and Alex Jennings' "A Knight in Tunisia". Not that that's a flaw—where will conflict come from, after all?—and it's amusing too to see in Ana Nnadi's "Hanfo Driver", anti-gravity tech that simply doesn't work that well once it's on the streets of Lagos.

What’s tricky, I think, is the short story form itself: certain stories involve such unfamiliar premises and lengthy worldbuilding, and once you've figured out what's going on, the tale's over. And because of the stories' diversity, and the relative obscurity of the history of Black and African SFF, it's hard to understand what's radically new about this era, aside from the fact that more folks from more parts of the world than ever can participate in a globalised SFF conversation. More of an intro, maybe even the individual story intros we had in Lavie Tidhar's Best of World SF: Vol 1, would've been welcome. Something to make the whole greater than the sum of its parts.

Tail of the Blue Bird, by Nii Ayikwei Parkes

Flipped Eye Publishing Limited, 2011

Here's an interesting find: a crime novel by a Ghanaian-British poet that’s uncompromisingly set in Ghana, not only incorporating words in Twi but actually italicising certain English words to show how some POV characters are borrowing them in Twi narration.

In one blurb, Emma Dawson talks about the end of the postcolonial novel; the absence of "apology". Sure enough, I feel like it's responding to an earlier generation of African novels (e.g. Bessie Head's Where Rain Clouds Gather, Ngũgĩ’s The River Between), which see a battle between feudal ancestors and modern progressive protagonists.

Our progressive protag here, the UK-educated forensic scientist Kayo (who actually modified his name so the English could pronounce it) finds himself thrust out of Accra into an investigation of a bizarre lump of human remains in a village hut, all while an abusive police inspector demands that he blow it up into a headline murder for the sake of promotion. What makes Kayo succeed, however, isn't his non-corruptibility but his deference to the village elders, specifically a hunter who reveals the true (?) story of what happened: (SPOILER WARNING!) a generational curse doomed a man who abused his wife and daughter to age backwards until he was nothing but a boneless heap of flesh.

And though Kayo's offered the chance to have $$$ and prestige if plays along with the inspector's game, he ultimately doesn't—he walks into the forest, back to the village. Reject modernity, embrace tradition, as the incels say. But then a lot of decolonial folks are playing with the same ideas: saying that even nativist modernities are deeply tainted, and we have to look to the peoples who are least glorified as civilised to gain wisdom.

Also re: no apologies. This work doesn't exoticise Ghana, showing it to be a land of cellphones and chemistry labs as well as leopards and revenant children and mysterious church organs that play in the jungle. The term magical realism comes to mind, but this isn't even that—it's just an acknowledgement that we live in a world where realities collide. And genres too, I guess!

Binti: The Complete Trilogy, by Nnedi Okorafor

Daw Books, 2019

This here's a prime example of what the author calls Africanfuturism: sci-fi that's deeply embedded in African (not just Black) perspectives—our teen mathematician wunderkind protagonist Binti isn't just a Black girl; she's specifically Himba, and much of the story centres on her otjize, the red clay she paints by custom on her skin and locks—an act that makes even the other humans in her country, the Khoush (themselves African), despise her as a barbarian, but which end up playing key parts in her role as an interspecies galactic peacemaker in the war with the jellyfish-like Meduse.

There's a lot to unpack in this tale, from Okorafor's oddly unlyrical narration to its truly multispecies imaginary of personhood—Oomza Uni, the planet where Binti goes to study, is only 5% human, populated by spiderlike, crablike, cephalopodlike fellow students and profs all of whom are acknowledged as People; to the extent that "it" is regarded as a perfectly valid personal pronoun (not a political accident: there are transgender human students too!)/ Even on Earth, Binti grasps communication with wild desert dogs, elephants and genetically engineered fish used as transport between the stars, and discovers that each species she bonds with actually alters her DNA and identity...

And yet, strange ethical questions arise. Isn't a Nigerian-American writing about a Himba just as culturally appropriative as, say, a Chinese Singaporean writing from an insider perspective on Orang Laut or Orang Asli? (As in, not exactly off limits but still kinda exploitative?) Also, Okorafor chooses to portray indigenous Africans as being masters of tech in the future: the Himba craft astrolabes, the universal comms devices of the future, and the Desert People are gifted a nanobot bloodline from aliens. But how does that square with redressing prejudice against "primitive" peoples? Are people only worth respect if they have tech? Nah: it's a genre thang—you've gotta have tech, or it isn't sci-fi.

What Is Not Yours Is Not Yours, by Helen Oyeyemi

Picador, 2017

OK, so this is technically a short-story collection, but it feels more like a gorgeous headache of a book, a hedge maze where you keep getting lost in gardens suffused with different botanical perfumes...

Lemme explain. The stories (which often aren't that short) keep disobeying the rules of the genre—simple plot, clear focus, clean endings—filling them up instead with all the weird extemporanea that belong in an experimental novel. "books and roses" begins with a foundling named Montserrat growing up in a Catalonian monastery, but evolves into two other full narratives of a lesbian thief-turned-painter named Lucy and Montserrat's servant-girl mother, before ending on her own oddly anticlimactic resolution; "is your blood as red as this" starts with the POV of Radha, in love with a puppetry student named Myrna, but the second and final section is told from the POV of one of her puppets, who appears to have a whole other social life besides observing the students, some of whom are puppets themselves...

And the tales are interconnected, each one featuring the motifs of locks and keys; also, characters reappear, though the stories are by no means set in the same world. Oyeyemi casually shifts genres, sometimes mid-story: "presence" morphs from a middle-class, middle-aged, marriage narrative to a sci-fi tale of a hallucinogenic drug; the miraculous climaxes only happen at the very ends of "if a book is locked there's probably a good reason for that, don't you think" and "'sorry' doesn't sweeten her tea".

Once again, magical realism comes close to describing what's going on—characters routinely talk to ghosts, but they're seldom sinister or explained or even relevant to the plot—but a more specific influence would be Angela Carter, with her specific love of the chaotic violence of fairytales. Two stories are straight-up, fairytale subversions: "dornička and the st martin's day goose" (a very clever take on Little Red Riding Hood) and "drownings" (set in a medieval-ish kingdom ruled by a tyrant whom our hero pretty much accidentally overthrows).

On the other hand, "magical realism" connotes Third World identity politics, and that's precisely what Oyeyemi wants to avoid (recalling what she said at NTU). Sure, lots of her characters are Black, but often it's only mentioned in passing (or revealed after their third appearance in a story, in the case of Tyche Shaw). and they're just as likely to be South Asian or Eastern European or Greek or Korean or even Malay (the protagonist of "a brief history of the homely wenches society" is called Dayang Shariff!).

Similarly, queer desire is routine and uncontroversial—quite a few parents are in same-sex, committed relationships. And while women's lives are front and centre of the story, there isn't much man-bashing: quite a few tales do focus on the sweetness of a woman being loved by a handsome man, whereas the final story (the aforementioned "if a book is locked...") dwells on the cruelty of women to women.

I know I'm falling into the trap of reductionism, but it does evoke the complexity of Black British identity, where even East Asian folks end up doing Black History Month events, and class and immigration status intersect at weird angles with race. Also, the bewildering and casual diversity of 21st century London, at least prior to Brexit. (This was first published in the tipping-point year of 2016.)

Now I wish I'd got to know Oyeyemi better when she was in Singapore—I too aspired to disorienting strangeness with my stories in Lion City, but didn't dare to assert myself so boldly, hiding my weirdest tales at the end of my book so readers wouldn't be scared off! I wonder, if like me, she began with crazy premises and let her characters wander off and surprise her with their decisions... or was there a premeditated method to her madness? If so, that intelligence scares me.

Black Leopard, Red Wolf, by Marlon James

Penguin Books, 2020

Damn, this is intense on multiple levels. The author's described this novel as "an African Game of Thrones", but that doesn't do justice to the extent and originality of its worldbuilding, nor the epically grimdark perversity of its violence—gory, sexual, institutional, and scatological.

It's the story of Tracker, a brooding badass with a superpowered sense of smell, telling the story of his life to an Inquisitor after killing a bunch of thugs in his jail cell. Eventually it morphs into his joining a motley team (including the giant Sadogo, the shape-shifting Leopard, the witch Sogolon, the mermaid Bunshi, the male mercenary and turncoat Nyka and the female mercenary Nsaka) to search through the many kingdoms of the land for a kidnapped boy who turns out to be a royal prince and potential heir to the throne.

And that sounds like a pretty standard secondary world fantasy, no? But be warned: pretty soon it becomes really difficult to follow what's happening, not just because of all the tons of unfamiliar names and foreign language dialogue and concepts (he's borrowing mingi from East Africa, griots from West Africa, sangomas from Southern Africa) but because his characters casually lapse into dreamworlds and lie and contradict each other, to the extent that when I checked Wikipedia to make sure I understood the plot of the story, I found out that Gautam Bhatia's praised it for how it "denies us refuge in meaning." (Good thing James got his start in literary fiction, which allows for such shenanigans: as a spec fic writer trying to make it internationally, I keep on worrying about pitching to the lowest common denominator.)

And it's interesting comparing this with idealised images of an uncolonised Africa, e.g. Wakanda, Zamunda, hoteps' projections of Ancient Egypt. Cos James takes all the barbaric stereotypes of Africa and rather than denying them, acknowledges their horror: slavery, despotism, cannibalism, child sacrifice for black magic—he even has some characters mock people for staying in cowdung huts (although I've visited some and they're fine?). And when characters do encounter a culture that resembles an Africanfuturist paradise—Dolingo, with its massive cabins suspended by ropes, led by a beautiful blue-black Queen, driven by high-tech White Scientists and with no slaves in sight—it eventually turns out to be the most horrific culture of all.

One last thing to appreciate: the portrayal of gay male love. This is a novel written by a gay man, not a yaoi-reading woman or enby, which is why we see all the violence and complication of that eros. Tracker isn't just a badass mofo, he's also a great lover of cock, and we see it in his intimacies and camaraderies even with straight friends, in the misogyny he has to work through, in the fact that he comes to vicious blows with the army chief Mossi before they finally go full-on enemies-to-lovers, flip-flopping in the belly of a slave ship... but how that doesn't mean they're going to end up in a monogamous, happy ending together, because our lives aren't that tidy, are they?

Basically, this work is a challenge, but if you've got the guts and the stomach, you can plough through this—just relax, stop worrying about what you're not getting, and let yourself soak in the blood and vibes.

Endnotes

[1] N.K. Jemisin, “How Long ‘til Black Future Month?” NK Jemisin. 30 September, 2013. https://nkjemisin.com/2013/09/how-long-til-black-future-month/

[2] Nnedi Okorafor. “Africanfuturism Defined.” Nnedi’s Wahala Zone Blog. 19 October 2019. http://nnedi.blogspot.com/2019/10/africanfuturism-defined.html

Ng Yi-Sheng (he/him) is a Singaporean writer, researcher and LGBT+ activist. His books include the short-story collection Lion City and the poetry collection last boy (both winners of the Singapore Literature Prize), the non-fiction work SQ21: Singapore Queers in the 21st Century, the spoken word collection Loud Poems for a Very Obliging Audience, and the performance lecture compilation Black Waters, Pink Sands. He recently edited A Mosque in the Jungle: Classic Ghost Stories by Othman Wok and EXHALE: an Anthology of Queer Singapore Voices. Check out his website at ngyisheng.com.

If you’ve enjoyed reading this article, please consider making a donation. Your donation goes towards paying our contributors and a modest stipend to our editors. Singapore Unbound is powered by volunteers, and we depend on individual supporters. To maintain our independence, we do not seek or accept direct funding from any government.

This Christmas season, Ng Yi-Sheng takes us to the Middle East.