#YISHREADS April 2023

By Ng Yi-Sheng / @yishkabob

April is National Poetry Month in the USA and the occasion for Singapore Poetry Writing Month (aka SingPoWriMo) here in Singapore, so I’ve decided to devote this month’s column to collections of poetry! But be warned: this isn’t a hot-off-the-presses survey of contemporary verse, but a ramble through my own eclectic library, more bewitched by history and spirituality than what’s fashionable or even objectively good.

So here we’ve got 4,000-year-old Sumerian hymns, 16th century Sufi poetry, 1960s Singaporean leftist verses, and 21st century feminist reclamations of Hinduism and queerings of Hong Kong’s Umbrella Movement. (I do feel terribly guilty about leaving out Wong May’s A Bad Girl’s Book of Animals, which I’ve read in both the original New York 1969 [1] and new Singapore 2023 editions [2], but I feel like that deserves a proper in-depth review rather than my own drive-by reflections.)

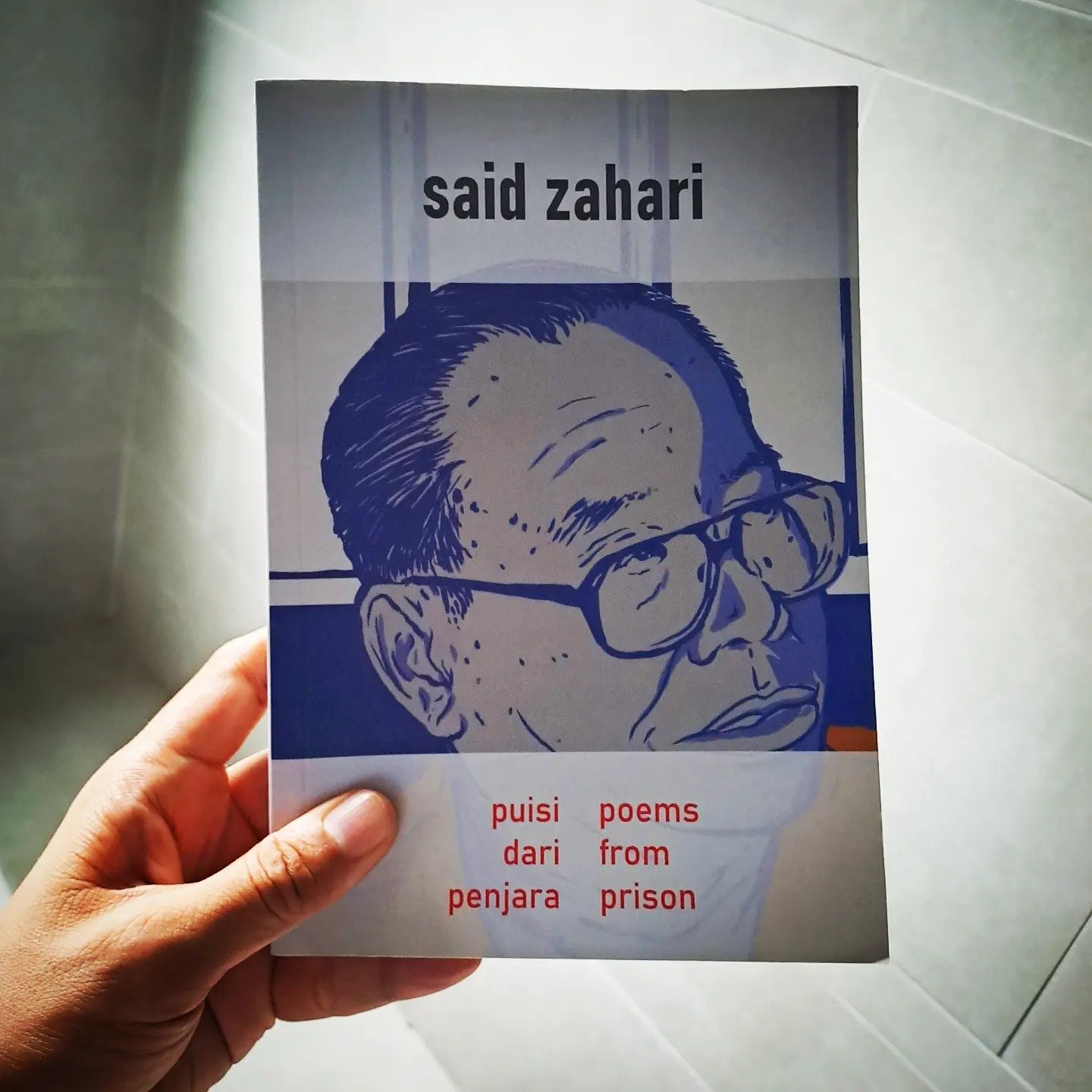

Puisi dari Penjara / Poems from Prison, by Said Zahari

Pusat Sejarah Rakyat, 2022

This is an imperfect work, but it's an important one! The author (1928 – 2016) is one of Singapore's most famed political detainees, arrested during Operation Coldstore and held for 17 years from 1963 to 80.

Back in '73, a pamphlet of his English-language poems was smuggled out and published under the same title, Poems from Prison. I'd read it before and it struck me as surprisingly good. Consider his reflection on the 1969 racial riots, "Hidden Hands", clear-voiced in its politics, clean and sonically resonant in its sorrow, devoid of pomp and obscurantism—far more relatable than the work of the pioneer nation-building poets at the NUS English Department at the time.

This book provides a much-needed archive of all 72 of the poems Pak Said wrote in jail (the extra 55 are in Malay), together with bilingual English/Malay translations by Adriana Nordin Manan with the assistance of Muhammad Haji Salleh, all on facing pages, so semi-bilinguals like me can shuttle easily between versions to grasp both the music and sense of the words.

Unfortunately, the book feels unnecessarily padded—there's a preface, three forewords, an introduction, and two speeches and a biodata as appendices, containing loads of redundancies and bloviating against the injustice of his detention. Plus, the translations are of pretty inconsistent quality—the very first one that appears, "Azam" / "Resolution", makes no grammatical sense! There seems to have been no real attempt to reflect Pak Said's idiomatic English here—though granted, he did seem to have had a thing for unnecessary archaisms, as seen in his English poems "Pusillanimous Lackey" and "Lass in White".

Frankly, a lot of the new pieces disappointed me—they felt like cliché truisms, barely worthy of being called poems. Then I reminded myself: these new poems were written in Malay, for personal reflection or private circulation, i.e. it's silly to judge them by the conventions of modern Western publishing. A poem titled "Pantun" is meant to be full aphorisms; his multiple Hari Raya and birthday and anniversary poems aren't meant to be deep; they're just reminders to others that he's alive.

Meanwhile, there are moving poems in here about the purpose of poetry and the meaning of freedom. Plus political poems so openly leftist that they're genuinely inspiring in their uncorrupted belief in Marxist futures: "Lagu Rakyat"/"Song of the People", "Vietnam Bebas" / "Free Vietnam", "Patriot Indochina" / "Indochinese Patriots", "Uncle Ho" (same title in both languages!), even "Darah dan Air Mata" / "Blood and Tears", in which he praises "Vietnam, Laos, Cambodia/names that shall forever dance on the tip of everyone's tongue,/names etched onto spears of bravery/lands of gallant patriots." (He wrote that in '73, two years before the Khmer Rouge began its reign of terror.)

In a time when Malay culture is so defined by Islam, it's thrilling to remember this other impulse, this other movement that's pretty much erased from our memory of its literature. And it's not like there isn't continuity: at the end of the book, we've got dedicatory poems in Malay/Indonesian by Usman Awang, Francis Khoo and Hersri Setiawan (a detainee of the Suharto regime), plus the very fact that this book exists thanks to the Pusat Sejarah Rakyat/People's History Centre in KL.

So, teachers of SingLit: can we reintegrate Pak Said into our syllabi? Can we resist the forces of amnesia and remind readers that writers and thinkers like this were part of our early history? His words are in print again, and we've a touch more freedom than in the days of Lee Kuan Yew. No excuse this time for silence.

The Altar of the Only World, by Sharanya Manivannan

HarperCollins Publishers India, 2017

A praise quote of mine appears on the front matter of this book! This was for the poet's first collection, Witchcraft (2008), which I adored and completely forgot I wrote about in The Straits Times.

This volume has the same deeply spiritual sensuality—the word "viscous" comes to mind, with all its honeyed intensity—all the heady language of divine longing and bliss of the Bhakti saints and Alvars, but in English with all its postcolonial flexibility, language both simple and arcane, old Greco-Latin imports mingling with unitalicised Tamil and Sanskrit. (A moment of delightful confusion: is udumbara cognate with umbra and penumbra?)

Yes, the vocab skates on the brink of teenage purple prose at times—it is, I think, a big risk to title a poem "Syzygy"—but even though Sha cites "the stories of Sita, Lucifer and Inanna" as inspirations, this isn't the show-offy multi-culti cosmopolitan buffet that a number of us 21st-century Anglophone writers, including me, resort to. She's anchored in Indianness/Hinduness—verses throb with images of Hanuman tearing open his breast, Ravana playing the lute with his guts, Draupadi bathing her hair in blood, Mariamman bringing rain, Krishna swallowing the sun, often never named, but invoked with the knowledge that her readers will know them.

Something I envy, really: as an agnostic Chinese Singaporean, I often feel my love with mysticism veering towards appropriation or try-hardiness. Gotta let my guard down, I suppose? Or just accept that some songs aren't mine to sing?

Emanations of Grace: Mystical Poems by A'ishah al-Ba'uniyah (d. 923/1517), edited and translated with an Introduction by Th. Emil Homerin

Fons Vitae, 2011

Picked this up from the Kampong Glam Muslim bookstore Wardah Books! They’re verses from one of the few medieval women Sufi masters who unambiguously recorded her own words in writing! (Rabia al-Basri was part of an oral tradition, it seems.)

Honestly speaking, the actual translated verses (all with nondescript titles such as “From his inspiration upon her (127-28)/(224-25)”) don't do much for me. Sure, the poet praises divine love by comparing it to the intoxication of wine; sure, she invokes the miracles of the Prophet and describes his beauty like that of a bridegroom. But Homerin doesn't sensationalise all that, placing it among a much-longer sequence of religious song, which clearly marks her as a defender of the Muslim faith: of this wine, she says, "if infidels could smell/the sweet scent of its bouquet,/they would submit/to the Muslim creed."

What's rather more interesting for me is the intro, where Homerin makes it clear that the poet wasn't gaining all her inspiration from wandering in the desert: she studied law and gained a reputation exceeding her brothers as an Islamic jurist; we still have the name of texts we copied so we know her philosophical influences. In other words, she's pretty well-documented, and we can see how she fits into a literary and intellectual canon that's mostly made up of men—so it's a little misleading to squeeze her into a global tradition of women's writing, as I'm wont to do. Turns out it's dumb to stereotype Sufis (or women writers) as being completely ruled by passion and ecstasy. Reason and dedicated study were also part of their repertoire, and we have to respect that.

Besiege Me, by Nicholas Wong

Noemi Press, 2020

This poet's just a year older than me—his poem “City Mess, Mother Mess, Fluids Mess” talks about being born the year of Margaret Thatcher's election: 1979—and he's got a briefer publishing history (his first book, Cities of Sameness, which I also enjoyed, came out in 2012). But I've gotta tell ya: he's a helluva lot more sophisticated.

I recently read his second book Crevasse, which dates from 2015: one of those collections that eschews pride in favour of dwelling on the physical discomfort of inhabiting a queer Asian male body, cf. Cyril Wong and Justin Chin, still haunted by the trauma of the AIDS crisis—see "Self-Portrait as Salmon Roe at Revolving Sushi"; "Meditations on How to Break Up with My Sick Boyfriend". But it's not just him and his body: he speaks for the city in poems like "Metro Public Bodies", "Postcolonial Zoology"... and maybe "Self-Portrait as Eeyore, to Pooh"? Can't remember if Xi Dada was already being compared to A. A. Milne's creations eight years ago.

Besiege Me is less focussed on the queer and good deal more overtly political, referencing the Umbrella Revolution in "First Martyr", "Apology to a Besieged City", the aforementioned "City Mess, Mother Mess, Fluids Mess"; even a direct satire of suppressive forces in "Advice from a Pro-Beijing Lobbyist" and the lacuna-filled "Dark Adaptation", imagining a Cultural Revolution 2.0 in 2052 to eradicate Cantonese.

Plus he’s interrogating Hong Kong's internal exploitation of Indonesian domestic workers in the long poem cycle "Vacuum"; he's wrestling with family, especially his paternal legacy, in "Intergenerational", "Biased Biography of My Father", "Biased Biography of My Mother", "I Swipe My AmEx to Cover My Father's Treatment for a Virus in His Lung I Don't Know How to Pronounce". Parent-child relationship as political metaphor and as stark reality of the ageing Gen-X-er.

But I shouldn't reduce Wong's oeuvre to simple identity politics and politics-politics; there's also daring experimentation, use of foreign language words, fantizi characters and radicals, diagrams, dialogue markers. All these representations of the inadequacy of printed English text to capture the turmoil of life in a late capitalist city-state caught between empires.

Inanna, Lady of Largest Heart: Poems of the Sumerian High Priestess Enheduanna, by Betty De Shong Meador

University of Texas Press, 2000

These days it's pretty common knowledge that the earliest recorded author was Enheduanna (fl. 2200s BCE), princess of Ur, daughter of Sargon of Akkad—her tablets were excavated by Leonard Woolley all the way back in the 1920s. (Agatha Christie's archaeologist boytoy Max Mallowan was part of that expedition!)

This 2000 publication, however, is probably one of the earliest widely available translations of her work, centred on just three hymns: "Inanna and Ebih", "Lady of Largest Heart" and "The Exaltation of Inanna". They're each fascinating in their own right, but given the strange and artificial process of translating a dead language from cuneiform, I can't take them at face value without considering the translator herself.

You see, Meador's principally a Jungian analyst and second-wave feminist who's not attempting very hard at all to distance herself from her subject. She's unabashedly looking for an ancient gynocentric alternative to patriarchal religion as part of a wave of Western New Age goddess worship, and she projects a proto-feminist agenda onto Enheduanna's glorification of the goddess. Hell, she prefaces the work by talking about encountering the goddess' ritual palm fronds in a dream about burying two of her analyst friends!

So we've gotta read these translations and interpretive essays with caution. Meador's arranged them to tell a biographical story of Inanna's triumphant conquest of the defiant mountain Ebih (which dares to be an Edenesque paradise where lion and deer lay down together without paying respects to her, to the order of nature), of her glorious reign and rituals, and finally Enheduanna's own undoing, as she is cast out of her holy sanctum by a man (whom Meador identifies as the historical rebel king Lugal-Ane) and pleads to Inanna for mercy.

All that being said: the hymns are pretty astonishing. Though there's a long lineage of women mystic poets, I don't think I've ever read a pre-modern example who's committed to a goddess: here we've got female-female divine erotics with Enheduanna imagining herself as Inanna's bride, preparing her bedchamber in the tavern (she was goddess to sex workers, among many other attributes!). Here there is a repeated smashing of gender binaries, not just in imagining the goddess decked out as a warrior but explicitly describing warrior women as her priestesses, men and women in her service muddling their genders. And here is a rare image of a supreme goddess as omnipotent but not omnibenevolent, as disasters and acts of cruelty are attributed to her too. "Vicious dragon you spew/venom poisons the land/like the storm god you howl/grain wilts on the ground," she writes in "The Exaltation".

Plus, the essays establish the canonicity of Enheduanna in a way I hadn't understood. It was she who established the role of head priestess after her father conquered Ur, i.e. she wielded real political power, pope-like, and her poems and 42 temple hymns (which I read in another, more boring volume [3]) were copied and studied for five centuries, as her religion did in fact withstand Lugal-Ane's rebellion and the rise of more patriarchal perspectives on religion. Strange that when educators try to shake up canons of world literature they reach for Murasaki and Austen instead of this poet!

Btw, I hear there's a whole new translation just out next month by Sophus Helle! [4] And free resources at https://enheduana.org/ , including a hyperlinked translation of "The Exaltation", if you're feeling too stingy to buy a copy.

Endnotes

[1] My review of the New York 1969 edition of Wong May’s A Bag Girl’s Book of Animals: https://www.facebook.com/ng.yisheng.9/posts/pfbid0zUDyL8m2oC5ioDGg1pZLTQXGvm1S45Gw9wLoVM46jxT2qhAyLQveVTYPdnPcY4mTl

[2] My review of the Singapore 2023 edition of Wong May’s A Bag Girl’s Book of Animals: https://www.facebook.com/ng.yisheng.9/posts/pfbid0AMFWNkkfPBHGRmtmGebKCqGsZq2PPR9AsXLqeYTRRc1xCAtcQYHCbRRg48dw4DVdl

[3] My review of Betty De Shong Meador’s Princess, Priestess, Poet: The Sumerian Temple Hymns of Enheduanna: http://world80books.blogspot.com/2012/02/book-89-iraq-princess-priestess-poet.html

[4] Sophus Helle, Enheduana: The Complete Poems of the World's First Author. Yale University Press, 2023. https://yalebooks.co.uk/page/detail/enheduana/?k=9780300264173

Ng Yi-Sheng (he/him) is a Singaporean writer, researcher and LGBT+ activist. His books include the short-story collection Lion City and the poetry collection last boy (both winners of the Singapore Literature Prize), the non-fiction work SQ21: Singapore Queers in the 21st Century, the spoken word collection Loud Poems for a Very Obliging Audience, and the performance lecture compilation Black Waters, Pink Sands. He recently edited A Mosque in the Jungle: Classic Ghost Stories by Othman Wok and EXHALE: an Anthology of Queer Singapore Voices. Check out his website at ngyisheng.com.

If you’ve enjoyed reading this article, please consider making a donation. Your donation goes towards paying our contributors and a modest stipend to our editors. Singapore Unbound is powered by volunteers, and we depend on individual supporters. To maintain our independence, we do not seek or accept direct funding from any government.

In Taiwan Travelogue, ‘twinned souls… are at once lost, but also found, in translation.’ A review by Eunice Lim.