Glass Animals

By Devanshi Khetarpal

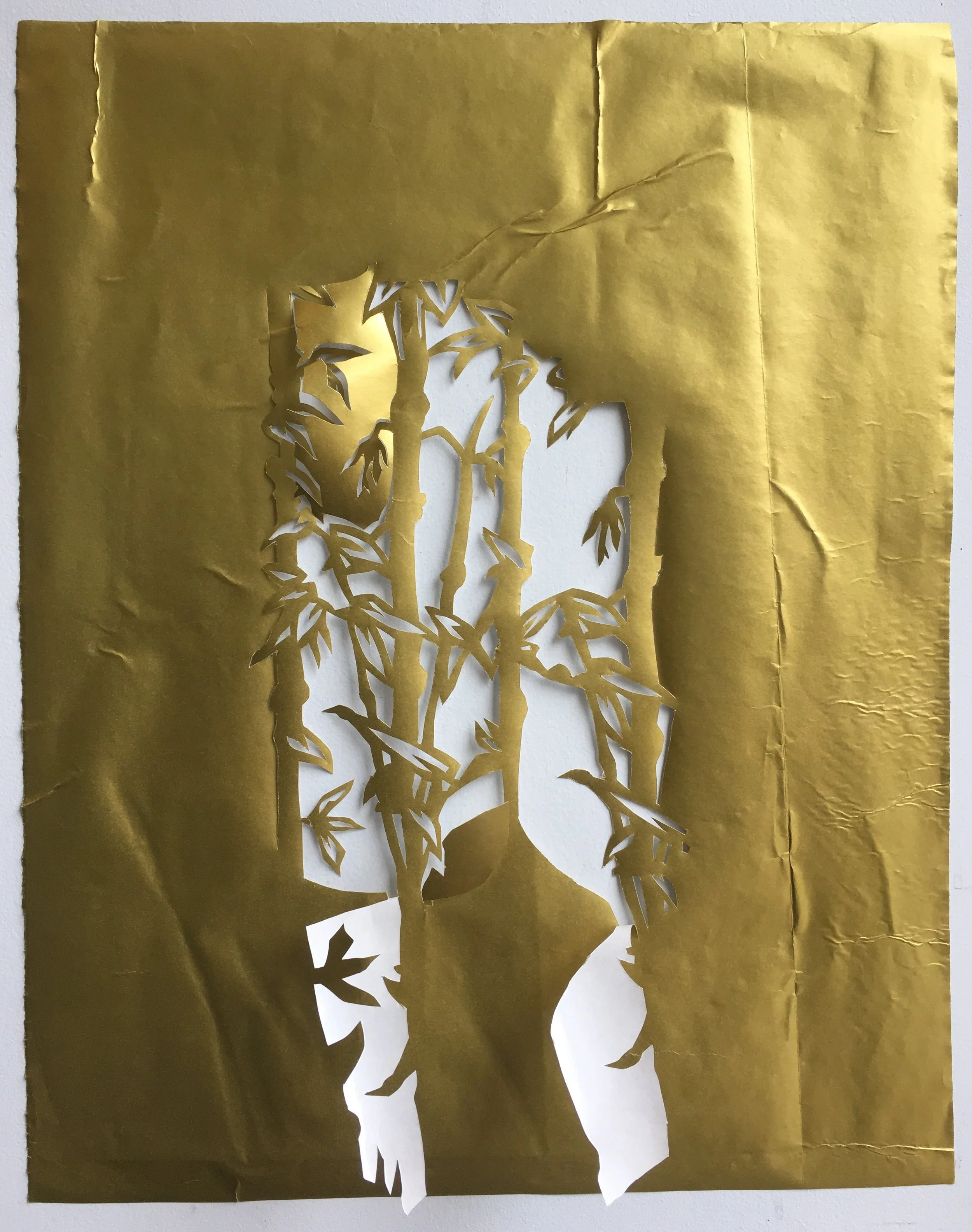

Catalina Ouyang - Lamia (2023), Concrete, plaster, pine, plywood, pigment, textile, papier mache, epoxy clay, hardware, gel medium transfers on aluminum, 40 x 58 x 8 inches. Courtesy of the artist and Night Gallery.

Image description: The installation comprises objects of various textures and shapes. Solid, gray blocks hold up a polished sphere with a long, thin piece of wooden stick attached horizontally to it. The stick goes through several thin, vertical panes of various sizes, on which an elongated, hand-shaped sculpture is balanced. Two photographs are attached along the stick.

Sapna called to ask if she could stay over. I was tempted to refuse, but she sounded rather fragile on the phone. Besides, I wanted to feel useful. The flat had become empty without Jai, the evenings so airless, so sober. Sapna and I hadn’t spoken in months since she moved to Delhi, and I was anxious to see her after so long. As our conversation neared its end, I agreed to let her stay, trying not to reveal my reluctance. I never found Sapna dangerous exactly, but there was something about her that unsettled me. She never questioned me about the affair, and she was strangely comfortable holding that difficult knowledge. Jai and I had moved in next door almost two years ago. Like any good neighbor, Sapna helped us unpack boxes, and find our way around the neighborhood, find a maid and dhobi. While Jai was away for a week to see his mother in Chandigarh that winter, however, Sapna saw Arjun trying to sneak out of our flat one morning. Arjun called me right after that encounter to tell me they had exchanged some awkward glances and words, that he made the mistake of telling her his name, that the shame on his face was revealing enough.

“You should clear the air with your neighbor,” he said. “She knows about us now.”

That evening, coming home from work, I caught Sapna alone on a bench in the society compound and sat down next to her. Before I could explain anything and provide my defense, precisely as I’d rehearsed it—a string of reasons and justifications, with stammers and pauses surgically inserted—she pulled my hand and cupped it in hers as she said, “Don’t worry, I won’t tell anyone.”

“We will not see each other anymore,” I said. I had practiced my lie.

“Well, don’t let me stop you from doing what you want to do.”

Something shifted between us then. I wasn’t relieved or taken aback exactly, but I felt disappointed, as though the grand consequence, the irreparable damage I thought I’d caused was a mere impossibility. I wanted Sapna to scold me. In front of her, I’d always felt an ancient urge to be a good woman, the sort who takes her education on these matters seriously, a woman who admits to indiscretion. But there was something about not receiving her contempt that made me feel twice as guilty and ashamed. I sensed Sapna could see the affair was nothing skeletal, nothing but sheer time-pass.

After that evening, Sapna’s visits to our flat became more frequent and I assumed this was the form of the transaction between us: she agreed to keep my secret safe and I, in return, entertained her. She would come over for small talk, chai, occasional dinners. She brought over muffins, samosas, gujiyas, and whatnot. I got the impression that Sapna wanted to feed me all the bad, indulgent stuff, so that I would carry the age of my marriage in my body like the women I saw growing up. I wondered if she wanted me to appear like an ill-fitting piece of clothing next to Jai who, like most men, never suspected the pattern of these things. He thought Sapna was one of those friendly neighbors who wanted to be friends, who brought things over and maintained relations and obligations, who cared for some mysterious reason about dispensable niceties.

But I quickly understood that Sapna never wanted to see just me. She took an interest in Jai or, at least, was beginning to. She wanted to visit only when both of us were present, not in an earnest effort to bridge the distance between us—as I would have preferred it—but to alert me to its existence. In those days, she made our marriage a game, almost a mathematical one, that made me feel I could measure our separation, jot down its false degrees, track its imbalances, check how it multiplied or shrunk over the course of a single day, weeks, months. And somewhere in the middle of it all, I suspected Sapna standing with an uncanny stability, bordering my outlines with a wispy saree draped around her, the pleats following her curvature with impossible accuracy. She donned such delicate pieces of jewelry, sometimes a silver chain with an unassuming but expensive pendant, or thin metal bracelets, a golden trellised watch, or a plain bindi. Occasionally, she paired her saris with a sleeveless cotton blouse, or a black, backless one with embroidered seams that deftly exposed the definition of her back.

I envied Sapna’s body. I often imagined her in the process of dressing up; I pictured her bony fingers blithely scheming her seduction. I didn’t want her body, but I thought through its index, its methods of persuasion. Whenever I’d glance at her from the kitchen— where I’d often be making chai during one of her visits—I would see her sitting on the couch, her legs suggestively crossed, laughing or chatting away with Jai who’d occupy his usual spot on his armchair, always the same, exhausted stance. Their comfort made me miserable, like I felt all those years ago in Bhopal. There, I felt like a useless matter of sorts, an order of business effortlessly ignored throughout the course of a busy day. Sometimes I felt erased in the most complete sense, like I was never meant to be in that city, in that family.

After all, Jai exchanged more words with Sapna in those few hours than he exchanged with me over months. In the early days of our marriage, I remember, we messed around or quietly read books or ambled in the city parks reliving our college days. But slowly, things had shuffled between us. It wasn’t dissatisfaction or boredom, or one of those textbook reasons that led to broken marriages. Our distance had no reason whatsoever. My relationship felt like a nausea that blurred my vision, that couldn’t be rescued by distractions and remedies alone. Something in those days demanded only transgression. When Jai learned about the affair—I told him casually one night, failing to hold it in any longer—he was most infuriated to know that it was with a friend of his. That knowledge punctuated his anger. He felt responsible, as if he had caused the affair to happen. He sat on the edge of the bed crying about a divorce, crying about how not inviting Arjun to cocktail parties and dinners could have saved us from the curse of his acquaintance. In the days that followed, things reached the slowest pause. Arjun and Jai stopped talking: they unfollowed each other on social media, left group chats unceremoniously, deleted each other’s phone numbers and emails. Jai began to sleep in the guestroom, and we only ever talked about necessary paperwork at meals. As months passed, he even refrained from the courtesy of doing the smallest of things for me; he wouldn’t pass me the salt at dinner, he started making his own chai and meals. Everything slipped notice between us. The house became messier, the dishes piled up in the sink, the bed was always unmade, the bathroom started to smell. Everything became permissible, no zones safe or risky enough for our relationship, and I began to spend more nights at Arjun’s apartment in Bandra. I was terrorized by what I’d done.

Catalina Ouyang - grief volume (Powder Mill; Anvil Ct; Mulberry and Grand) (2023), Textile, school desk top, steel, brass, hardware, hedge wood, pine, plaster, epoxy clay, acrylic gel transfer, oil paint on panel, drywall panels, and soapstone, 28 x 19 x 62 inches. Courtesy of the artist and Lyles & King.

Image description: A multimedia installation features objects of various textures and shapes attached to a beige panel. On the left, thick, pink matter forms round blobs, resembling organic forms. A long, white tube points upwards and is covered by a thin, gray mesh. A piece of stone and cloth are layered on it. Below it, an abstractly-shaped, long, thin piece of wood stretches downwards. On the bottom right corner is an image depicting two human-like forms.

One day, to resuscitate something—I am not quite sure what—I tried kissing Jai while he was getting ready for work. Jai kept on going, buttoning his shirt and combing his hair, trying to stop himself from shoving me away. And I kept kissing him dispassionately, feeling the mechanics of his burdensome routine against my body. I disgusted myself. Sometimes I believed that the tension between us had turned us into glass animals or made a warzone out of our flat, that onlookers were squinting to watch us from afar and would come around any moment to inspect the damages and tally the casualties. Our emergency was clear to everyone, I thought, and Sapna was no stranger, of course. She continued to come by in the evenings and Jai acted gregarious in her presence, laughing in the most shamefully revealing manner. And I began to observe her, almost clinically, when she was with Jai. The truth is, I felt afraid of the two of them. In their presence, I felt reduced to a veil, only a shelter for something that was already coming undone.

I remember how I ran into Sapna once at the mandi on my way back from work. We discussed inflation, the rising costs of running a half-decent home, the arrests and protests. She told me about the benefits of eating organic produce, about some online purchases that were making her life significantly and genuinely—she stressed on that latter word—easier. But I knew the conversation would inevitably change its course, that it would return to the confidence between us, even if it was no longer sacred or ours alone.

“I am telling you, this happens in every marriage,” she said, abruptly.

“Were you ever married?” I asked her.

She nodded reluctantly, as if my question had offended her. On the way back home, my mind was racing and I continued to make guesses about Sapna’s marriage. Was she still married to him or were they divorced too? Where was her husband? Why did it end? I thought about her getting all dressed up before meeting Jai, her conversations with him, and suddenly it all seemed clear and rehearsed. I wondered if Jai reminded her of her husband, if there was something in him she could not unsee.

Our divorce was not Jai’s first encounter with disappointment. In his own words, his parents’ marriage was “chaotic and alcohol-addled,” and they had separated when he was merely five years old. Although his parents never struck me as alcoholics, I accepted that this could have been the all too typical narrative of households like his. Families like mine, after all, fell apart because of more provincial issues. Where I grew up, we heard mostly about dowry deaths and caste conflicts, domestic abuse and violent families. Our alcohol was of a different kind, bought by hoards of skinny men from the desi sharaab stall around the corner of GTB Complex. Our divorces didn’t revolve around the jargon of infidelity or incompatibility, chaos or boredom. My own affair was a kind of upgrade from the catalog of marital miseries I came from. In fact, I was even proud of it, as if it declared my social ascension into urban, upper-class India. I was almost certain that my parents, too, were slightly relieved by my infidelity, that it strangely ascertained my escape from their world, their ranks and attitudes. I had reason to believe they might have even framed and hung my divorce papers alongside my degrees, or put in on display next to trophies from debating competitions at school. Perhaps Sapna and I had had a similar socio-economic reckoning that brought us closer. She was a lonely woman in the city, after all, passively guarding the truth about her marriage, living a comfortable but uneventful life. And I was inching closing to becoming her.

While I was never invested in my marriage, I was all too mortified by the idea of letting go entirely. I was afraid of divorce, of having to give measured, silent nods to questions about me and Jai. My relationship to him was like a private dialect, or an appendix that ran through the most routine of my thoughts and actions. When our marriage fell apart and he moved out into an apartment in Juhu, I felt as though my body had embarked on a process of disintegration as well. I noticed my breasts sagging, my skin breaking out. I lost my appetite and shed a few kilos. I couldn’t focus on work. I was embarrassingly careless and took the wrong turns while driving to work. I thought my erosion would seem strangely inviting to Jai, that he would construe it as my way of screaming for him, desperate for him to return. And a part of me did want him to notice me and see my depravity, my starvation whenever he’d stop by to collect his things and pack them into boxes. But I also held steadfastly to the view that there was something else at play, something that was brought into effect long before my infidelity, even long before my marriage to Jai. I felt as though a tumor in my body was finding a channel to grow and spread, consuming me from within.

Somehow Sapna was the only person whose presence never caused me any real damage. Despite her attempts to seduce Jai or to pull him away from me, she didn’t ever wound me. Instead, she protected me and exposed me to myself. I wondered if Sapna had ever cheated on her husband, or if her husband had cheated on her. Perhaps that was why she understood the course of my marriage. Perhaps that’s why I felt the urge to keep some distance from her, to resist her attempts at infecting my life. But my agreement to let her stay over that night marked the failure of that mission. I wondered what she was going through, what exactly she wanted, why she thought of asking to stay over. What couldn’t Sapna say over the phone? What was making her return to Bombay?

In the days leading up to Sapna’s visit, I prepared the spare bedroom, cleaned the bathroom multiple times. I stocked up on groceries and toiletries, just in case. I bought a few clothes for her to wear. In the supermarket the evening before, I felt like I was preparing for a child to enter my life, as though I was gathering provisions before a storm, guarding something before an incursion. But it was true that I was arming myself and hoping for Sapna to remedy the emptiness of the flat I used to share with Jai. That night, as I scrolled through the aisles in the store with the daily news roundup sounding through my earphones, my mind conjured images of tragedies and disasters, and I became sad thinking my domestic tragedy, whatever made me anxious paled in comparison and yet, I felt simultaneously threatened and prepared for all disasters, something I didn’t experience during my marriage to Jai, or even during my affair with Arjun. With them, any notion of space, boundaries and territories— the decision to capture or relinquish— didn’t come to mind at all. On the contrary, it seemed as though I had entered a space that had always existed, that wasn’t ever mine to begin with. With Jai and Arjun, I became a body that could be entered, a body that neither fulfilled nor feared them. Maybe nothing more and always something less, if only someone bothered to ask.

I looked around the apartment once more before the clock struck six. Sapna was always on time. I made sure I had restocked my refrigerator. I scrolled through blogs and confirmed cooking times even for things I made every day without issues. Until minutes before her arrival, I continued cleaning and dusting, and put on some light makeup for the first time in months, making sure that my home not only seemed presentable, but completely uninhabited, without signs of decay or loneliness. I erased every trace of my indifference. When the doorbell rang, I was thinking of other matters: the affair itself, my marriage to Jai, the house falling into disrepair years from now.

When I answered the door, Sapna asked, “Did I interrupt something?”

I must have seemed perturbed, not entirely myself.

“No, no, come in. Good to see you,” I said, rather distractedly. “Make yourself comfortable.”

She was wearing a plain but elegant salwar kameez that time; she had tied her hair up. It was a look that suited her best, I thought. I wondered if her inclinations towards Jai had something to do with this peculiar visit, if she wanted to experience her fantasy of living in Jai’s house, sleeping and waking up in the bed, the room that was once his. Perhaps this was the closest she wanted to be to him. I understood, of course. I remembered how I enjoyed waking up next to Arjun in those days, how it was that ability to partake in the same morning light and routine, the same objects and surfaces reflecting their light on our bodies. I knew far too well what speaking that private language with someone else felt like. But why Sapna wanted to speak that language then, I could not bring myself to understand.

I asked her the customary questions: how are you doing? What have you been up to? Sapna told me a bit about Delhi, how they were dealing with the violence, the protests, the pollution.

“I like my life there, and I like Delhi. But my new neighbors aren’t quite as kind as you and Jai,” she added.

I smiled, and she paused before asking, “So you’re divorced now, right?”

I nodded. To my own surprise, I didn’t feel anything at all as I said it.

“I don’t miss him,” the words slithered out of me, but I quickly corrected myself. “Sorry, I don’t know why I said that.”

Sapna looked at me with a knowing expression on her face.

“Don’t be sorry, I understand. It’s okay to tell you this now, but he was looking at my cleavage once, you know,” she said, “when I first came over.”

Perhaps I didn’t seem appalled or surprised enough, so Sapna went on to detail his gaze. She described it, with words so carefully chosen that they sounded like a practiced fiction: “his gaze was predatory, slow, something insidious or venomous.” I was uninterested although I knew she was trying to help me. She must have thought I needed help, or I must have looked the part. A part of me wanted to blame her that night, however, to tell her that I could see through her, through the draping of her sarees and the jewelry she decided to wear. I wanted to tell Sapna that she wasn’t saving anyone, that she couldn’t purge the relics of my marriage either.

“Do you still speak to Arjun?” she asked me, cautiously.

“No,” I replied. “I don’t speak to anyone. I am just doing my own thing right now, you know.”

Sapna acquiesced and didn’t press further. For the rest of the night, our conversation maneuvered rather tediously before it gained some momentum. I almost wished Jai was there, if only to bridge our small and awkward gaps and pauses. Without him, I was left feeling I had nothing interesting to say, nothing of substance to add.

“You reading anything good?” she asked me. “I remember you read a lot.”

I smiled, “Yes, I am reading a collection of poetry. Do you know anything about poetry?” I asked Sapna.

“I am afraid I do not,” she said, resignedly.

I showed her the collection I was reading—Stag’s Leap by Sharon Olds— and she turned the book around in her hands, flicking through some pages. Conversations about books had never been easy for me, especially with someone like Sapna. Even Jai never understood or had the patience to comprehend my love for poetry, in particular. To him, it was another odd detail about me, another quirk that enchanted him at first. I was not quite sure if I could explain to Sapna my love for storytelling, for language and narrative. It was not a territory she could encroach upon so easily. My passion for reading went far beyond my college days, my degrees in literature, my work at the publishing house, my childhood. And in a way, I desired to read Sapna like a book, to trace my fingers along her edges and turn her over and around in my soft hands. It was a desire that I purposely wanted to keep unfulfilled, even if its containment demanded everything of me.

Dinner was almost ready when things grew quiet between us again. It was the kind of silence that made me feel Sapna and I were about to arrive together at points of no return. I was not prepared to unravel. I laid out the fish curry and pulao on the table, along with some rotis and sabzi, and a beetroot salad. She took a bite of the food and I waited for her comments.

“The fish curry is really nice. Did you follow a recipe from somewhere?” Sapna asked.

“I just looked up a recipe online. Nothing special,” I lied.

It was Arjun’s recipe. She was right to not trust my abilities. Arjun loved to come over and cook for me, and it was one of the reasons I didn’t loathe him. He helped with housework, he asked me questions about work and although he was more inflexible about certain things than I—wine glasses only for wines, the china only for date nights, rice and curry to always be eaten with one’s hands—he was considerably adept at seeing and understanding others. Jai was the opposite in many ways. Like the best of husbands and fathers, his efforts began to wear off, and he could no longer keep up with the man he wanted to be at the beginning of our marriage. He grew more exhausted and wanted to fit more rigidly into the world. Jai and I never talked about children. We were both aware of our silence on the issue. We could sense when the other was inching close to broaching the subject in conversations, about to disturb that tenuous peace. But there were so many signs of wreckage between us, that I was surprised we survived for as long as we did.

I watched Sapna eating her food carefully, slowly, while the dulled wounds of history singed in my mind. I couldn’t blame her for being rude or ill-mannered, even if she threw surprises my way at times. I told her I miss her.

“We should do this more often,” I proposed.

“Yes, maybe you come over to my house next time?” she said, smiling. “You haven’t seen it yet.”

“Of course, I haven’t been to Delhi in so long. I want to see where you live now.”

“You know, I think you and Jai would’ve made good parents.”

I looked at her puzzled, as if she had read my mind. I asked her, the words rocking gently back and forth before they left my mouth, “Had you ever thought of having kids?”

I used the past tense deliberately. Sapna looked at her plate and stopped eating for a moment before proceeding to look me in the eye. She still had one of those faces that could not be read, that never allowed themselves to be torn apart from the seams. I let her silence soak into my skin, flood my walls. It was as though the objects around us—the plates, forks, knives—suddenly became porous and absorbed that stillness, filled with the anxiety of that moment.

“I did, yes,” she said, quietly.

Her answer didn’t surprise me, but my question seemed inane upon reflection. I didn’t say anything more. I failed to imagine Sapna as a mother. I’d always seen her alone, coming and going out of her flat, planning the next visit, getting ready to see Jai. I leaned in to touch Sapna’s hand, but stopped myself instinctively. I wanted to thank her for teaching me how to be alone. But we continue eating silently, sharing only some laughs about the songs we used to dance to, the movies that moved us in the 90s which we began to find utterly ridiculous as we aged. I served us some dessert and guided her to the guest bedroom. I showed her the bathroom, I demonstrated the functioning of the light switch and the finicky shower. I told her insincerely to knock on my door for any reason whatsoever at any hour of the night, and retreated into my bedroom. I had even picked a pair of night clothes for her, with fresh towels and toiletries too that I’d placed with an evident gentleness on the corner of her bed.

“I have everything with me,” she said in a way that was as assuring as it was insistent.

As I lay in bed, I could feel Sapna’s presence in the house throughout the night, as though all the pictures were rearranging themselves in their frames with every step she took, as though everything was changing in color, all the shelves suddenly changing shape, the furniture exposing the defects of its making. I wanted to move like her, like a vastness without sound, as if under surveillance, curbing all my urges and desires. Like Sapna, I wanted to become some kind of outline.

In the middle of the night, I was woken up by the sound of clanging cups and plates in the kitchen. I rolled out of bed laboriously. Sapna was there, hunched over the stove, boiling some water for chai. She hadn’t changed her clothes, but they looked new on her somehow.

“Is everything alright?” I asked.

“I couldn’t sleep,” she said. “Sorry for the disturbance, I didn’t mean to wake you. Would you like some chai?”

“No, I am alright. I think I’ll go back to bed, if you don’t mind.”

Sapna gave me a small, apologetic nod.

“Before you go,” she said, “Can I tell you something?”

I turned around to look at her, rubbing my eyes while she took a deep breath with her eyes closed. She proceeded to take my hand and we sat down by the dining table. The water continued to boil in the kitchen; I was mindful of that sound, but kept my gaze fixed on Sapna.

“You asked about kids,” she said.

“Yes, I did, I am sorry. If you’re uncomfortable with the subject—”

I left my sentence unfinished. And I looked at her more carefully, her lips parting in preparation to speak.

“My son—he was a few days old—we used to live in this apartment. Six years ago, my husband and I were bringing him home from Leelavati. Maybe I was holding him carelessly. But he slipped out of my arms, down the bottom of the stairs and died right there,” Sapna said, rushing out the door to point at the exact spot. “Come here, and look,” she said feverishly, leaning over the railing. I hesitated, and took slow and measured steps to peer down the staircase. I watched her face—she did not bat an eye, her fingers appeared frigid as metal. As I kept looking at her, I thought I was seeing her for the first time. I realized that her face bore the slightest resemblance to mine, and I could see the thoughts crossing her mind.

Catalina Ouyang - syndrome (2023), Papier mache, textile, discarded elements, steel, brass, oil paint, paper, oak, pine, pet staircase, acrylic gel transfer, hardware, wire mesh, wool roving, plastic, resin, 42 x 72 x 40 inches. Courtesy of the artist and Lyles & King.

Image description: The multimedia installation features a large, thickly-textured form, which is shaped to resemble a human bending down. White structures stick out from its head, and it only has upper arms. A small, brown object is balanced on its back. On its right are three sculptures resembling differently-shaped shoes. Behind them, a wooden staircase with four steps is balanced on its own, with a sculpture of a boot on the first step. To the right, a large, gray block holds up a ball of black wire, behind which is a tall, thin structure.

Devanshi Khetarpal is a Truman Capote and Sonny Mehta fellow in Fiction at the Iowa Writers' Workshop. She is the editor-in-chief of Inklette Magazine, and her work has been published in Public Books, Poetry at Sangam, The Bombay Literary Magazine, and Vayavya, among others. She holds a Master's in Comparative Literature from New York University, and her work has been supported by the Juniper Writing Institute, Bread Loaf Translators' Conference and Yale Writers' Workshop. She was longlisted for the 2023 Toto Award for Creative Writing. Her poetry collection Small Talk was published by Writers Workshop, Kolkata, in 2019. She is from Bhopal, India. Website: www.devanshikhetarpal.co.

*

Catalina Ouyang’s interdisciplinary practice embraces an array of materials including hand-carved wood and stone, appropriated literature and film, family secrets, animal parts, antiques, and a replica of a trench toilet, presented with varying degrees of legibility. Against affirmational conventions of representation and repair, the works instigate relation through violation.

Based in New York, Ouyang received an MFA from Yale University. They have held solo exhibitions at Night Gallery, Los Angeles; No Place Gallery, Columbus, Ohio; Lyles & King, New York; Knockdown Center, Queens; and Make Room, Los Angeles. Their work has been reviewed and featured in the New York Times, Artforum, Flash Art, Momus, Sculpture Magazine, Office Magazine, Document Journal, ArtReview, and Frieze; and is in the collections of the Brooklyn Museum; High Museum, Atlanta; Pérez Art Museum Miami; Nasher Sculpture Center, Dallas; Columbus Museum of Art, Ohio; Kadist Foundation, San Francisco; Faurschou Foundation, Copenhagen; and X Museum, Beijing.

If you’ve enjoyed reading this article, please consider making a donation. Your donation goes towards paying our contributors and a modest stipend to our editors. Singapore Unbound is powered by volunteers, and we depend on individual supporters. To maintain our independence, we do not seek or accept direct funding from any government.

‘The first clean air came quietly. Felt wrong, almost. Like walking into your house after a funeral.’ – A short story by Ian Mark Ganut.