Art, Music and Statelessness in Sabah

By Erel

I first met Drop on a school trip to Semporna. He was a student at an activist organisation in Sabah that provided informal education to stateless Bajau youth. Entering the school, he waved a quick greeting to his peers, nodded curtly to the strangers from Singapore and lit a cigarette. Though I was initially stunned at the brazenness of smoking within school compounds, I swallowed my shock—Malaysia boleh, after all—and asked for a cigarette.

Drop - Rumah Adat Di Bakar (2024)

Image description: A watercolor painting is displayed against a grainy, brown backdrop. The painting depicts a wooden house. The roof of the house is on fire. The house tilts to the right, as if about to topple. A body of water is in the background. The painting is rendered in broad strokes.

Smoking, like eating, can be a social activity. Every shared smoke is a peek into my interlocutor’s life, a translucent windowpane to peer through. This particular exchange, however, was severely impeded by language barriers.

Passing me a cigarette, Drop nodded his approval. “Rokok bagus,” he said. Cigarettes are great. That I understood, but not much more. Later, to my horror and amusement, he’d tell me of a passion for smoking so great that, in spite of his lungs having previously collapsed, he’d persevered with the habit.

Over numerous trips to Semporna, I came to know Drop fairly well. An artist, musician, diver, activist and student—what couldn’t he do? But behind his nonchalant facade was a burning anger at the hand dealt to him and his community by life and by, if I was bold enough to say, the Malaysian government. Marginalised, silenced and stateless—all par for the course in the life of an average Bajau person in Semporna.

The Bajau people is an indigenous ethnic group primarily populating the east coast of Sabah and Southern Philippines. However, they are historically sea-nomadic, moving across maritime borders within the Sulu Sea. This way of life makes it difficult to define the geographic boundaries of their homeland, or more accurately, their homewaters. Since the region they inhabit and traverse do not easily map onto fixed nation-states, authorities find it difficult to define their nationality. Colonial governments viewed the Bajau people as transient and difficult to govern, thus failing to integrate them into land-based citizenship frameworks. As Malaysia, the Philippines and Indonesia gained independence and national borders solidified, many Bajau people in Sabah were left out of state registration processes.

Crucially, under the National Registration Act of 1959, all Malaysian citizens are required to be registered and issued an identity card. The current identity card, or “MyKad”, introduced by the National Registration Department in 2001, serves as proof of citizenship and is necessary for accessing state services, education and fundamental rights. One requirement of the registration process is documentation of a permanent address, meaning that nomadic Bajau people, with no legal proof of residence, are unable to fulfil this criterion. Furthermore, many Bajau people live in remote areas or islands, and travelling to a civil registration office would be logistically difficult or would incur unaffordable financial cost. Today, though many have settled in more accessible or urban locations with permanent addresses, there remains multiple barriers to obtaining the MyKad, including the need to provide birth certificates or proof of at least one parent’s citizenship, which is often impossible for children born to stateless parents.

“Introduce yourself,” I asked Drop. “For the essay.”

“Hai, on ku Drop, ummul ku 21 battinaan aku pattak ma sampulnak, Kampung XXXXX.”

Hi, my name is Drop, age 21, and I currently live in Kampung XXXXX.

His kampung, safe to say, was a far cry from what I was accustomed to in Singapore. Houses built on stilts extend far into the Celebes Sea, each painted a vibrant blue or green or pink or red, individualised beyond the greys and glass of a regulated metropolitan city. Within the kampung and to other islands and kampungs, most travel by boat, weaving between stilts and under bridges to merge into larger boulevards of sea expanse. With the kampung situated just outside the urban area of Semporna, many also commute by car or on foot to town, forsaking a heritage of fishing to work menial jobs. Come evening, a throng of people would crowd onto the wooden planks on their commute home from work, sending the bridges swaying with the threat of a quick fall into the water below.

Like so many other Bajaus, despite being born and raised in Malaysia, Drop has no citizenship. He is stateless, his application for documentation indefinitely pending.

As a Singaporean university student from an upper-middle class background, my own privileges meant that I had near nothing in common with Drop—save one thing. Drop, I soon discovered, shared my passion for music.

“Kamu tahu Creep?” he asked one day.

“By Radiohead?” I responded.

“Betul.”

He knew the chords on guitar, and I karaoke-d along. On a separate trip, I’d attempt to accompany him on a rusty toy keyboard, but the make-shift piano set-up didn’t quite cut it. “Sangat kuat,” he laughed over the discordant notes, using simplistic Malay vocabulary for my benefit.

For Drop, music gave meaning to a tough childhood. He started working at the age of eight, he told me on my last trip to Semporna. Fiddling with his phone, he lay prone on the luxurious sheets of my hotel bed, a commodity he found foreign—he was accustomed to sleeping on floors and cramped mattresses, and his favourite place to rest was the mossy ground of a rainforest. He worked in construction, he said.

“At eight years old?” I questioned. “In construction?”

“Betul.”

That’s illegal, I thought. That’s child labour.

But the law is often indifferent to those most in need of its protection.

After receiving a year of education in pre-school, at age seven, Drop was unable to continue in the mainstream school system. Public schools are only free for citizens, and Drop’s family, lacking his documentation, could not afford to continue his schooling in Tawau. Searching for alternatives, Drop’s mother sent him to an Islamic boarding school, but mounting financial pressures forced Drop to drop out the following year and begin working to help his family put food on the table.

“Ketika kanak-kanak lain seusia saya menikmati masa bermain, saya sudah mengangkat batu bata, mengaduk simen, dan mengetuk kayu seperti seorang dewasa.”

Other kids could play, live, be carefree, as a child should be. Drop was lifting bricks, mixing cement, and hammering wood. The difficult childhood he faced left an irrevocable mark on his health. He doesn’t see too well, he told me, and the sedimentation that chokes the air of construction sites has eroded the pink of his lungs. Sometimes, his back hurts.

Music was solace in this hardship. Drop comes from a lineage of musical artistry—his father’s family played a variety of musical instruments, from traditional to modern. His grandparents often played the gabbang, a traditional Suluk percussion instrument, his grandfather playing the gabbang made from animal hide while his grandmother played the one made of iron. Sometimes, his grandfather’s friends would join them with a chorus of traditional instruments, singing and the occasional violin.

“Suasana ini sangat merdu dan sering membuat saya tertidur.”

First, Drop tried the drums. He asked his uncle, a musician in the kampung band, to teach him. At eight years old, he wasn’t strong enough to hit the drums. Not his thing, he decided. Then, he tried the guitar. This one stuck.

“What type of guitar did you have?” I asked.

“Gitar biasa saja,” he answered. “Tiada brand.” The guitar was borrowed from a friend’s father, handmade from plywood. Every night, Drop would head over to his friend’s house to practise, relentlessly bugging his peers and elders to teach him chords, fingerings, scales, songs. Eventually, he could pick up songs by ear alone.

“You mentioned you like writing lyrics in your free time,” I said. “What do you write about?”

By this time, we had begun speaking almost entirely in English. Though I attempted to learn Malay, my lack of confidence and practice in the language meant that Drop’s spoken English ability quickly overtook my spoken Malay ability. It is a deep regret of mine that our verbal communication was in my language rather than his, limiting his ability to speak freely. Yet again, someone from a marginalised community was made to accommodate a person more privileged than them.

Drop made a noncommittal noise. “About rakyat, about government, many things,” he answered.

“Macam politik ah,” I asked.

“Iya.”

“What’s your political stance?”

“Huh?”

“Like, communist, capitalist, whatever. Ideology lah.”

“Oh, faham. Tiada ideology lah. I just want everybody equal.” In his conversations with myself and other Singaporeans, Drop had begun to adopt “lah” as part of his vernacular.

“Equality?”

“Iya. I don’t want people suffer.”

Drop often makes mention of what he calls “punk”. Punk ideas, attitudes, beliefs. On my first trip to Semporna, he remarked on my piercings and tattoos, and called them “punk”.

“If I not Muslim, I want,” he said, pointing to my tattoos. “But haram.”

“Punk”, in Semporna, was more than a music-based subculture. There was no separation of punk, goth, emo, metalhead or whatever micro-label that’s slapped onto a new niche of music. Instead, “punk” was everything alternative, everything rebellious, from music to fashion to participation in demonstrations. Punk was a refusal to succumb to the status quo.

Walking down the streets of Semporna, on account of my alternative appearance, I occasionally get glances from young men sporting band T-shirts, who’d perhaps say hi or raise their hand clenched in the quintessential devil horns associated with rock-n-roll. Drop explained: the punk community in Semporna was small and tight. Their friendliness was a mark of solidarity.

Drop’s music doesn’t sound punk in the traditional sense. No harsh distortion, no angry shouting. But at its essence is an inherently punk ideology. In his free time, Drop writes his heart out, weaving subversive lyrics of protestation.

Kad biru yang berkuasa, untuk selamat dari penguasa

Rakyat miskin menderita, pemerintah bahagia

Kad biru—“blue card”—refers to the Malaysian identity card. Lyrics from Drop’s song portrays the kad biru as an unattainable privilege for many Bajau people in Sabah. As dictated by the Immigration Act 1959/1963, those without documentation are classed as illegal immigrants. Stateless Bajau people are thus under constant threat of arrest, imprisonment and deportation. Deprived of the kad biru, as Drop sings, poor people suffer while the government sits happy.

Recently, Drop has also begun honing his skills in visual arts. His Instagram features a slew of political posters, each handcrafted with painstaking care. “SELAMATKAN NEGARA DARI KORUPTOR” or “save the country from the corrupt”, says one. Another features the word “CORRUPTION” in English, plastered over a cast of caricaturised Sabahan lawmakers.

Though Drop used to make political posters using paper and printing, he has since gone digital. He uses CapCut to remove backgrounds, Adobe Illustrator to draw and edit and Canva for typography. Posters, he told me, are a form of protest for him.

Currently, Drop is receiving informal teaching from controversial political artist Fahmi Reza. Most known for caricaturising then-prime minister Najib Razak as a clown amidst well-substantiated allegations of corruption, Reza has recently been detained and jailed for his caricature of Musa Aman, the incumbent Yang di-Pertua Negeri of Sabah, who is accused of corruption and money laundering, including receiving US$63 million in bribes.

Drop also takes on local design jobs and participates in art competitions. Recently, he took a job designing artwork for a marine conservation organisation based in Malaysian Borneo. He is also participating in a competition to design the logo for a non-profit developing alternative education programmes for underprivileged children.

“Di mana kamu melihat sendiri dalam masa lima tahun?” I asked him. Where do you see yourself in five years?

“Dalam lima tahun akan datang, aku membayangkan diriku sebagai seorang artis visual dan penulis lirik lagu protes yang berkomitmen untuk membawa suara masyarakat terpinggir ke dalam karya-karya grafik design dan lagu-lagu ku,” he wrote to me.

“Aku ingin menjadi lidah bagi masyarakatku yang sering kali tidak didengari, khususnya masyarakat stateless yang menghadapi pelbagai cabaran dan ketidakadilan.

“Sebagai seorang artis, aku percaya bahawa seni mempunyai kuasa untuk mengubah perspektif dan membangkitkan kesedaran. Dalam setiap lukisan, poster atau rekaan grafik dan nada, lirik lagi yang aku hasilkan, aku ingin menyampaikan cerita-cerita yang tidak pernah diperdengarkan. Isu-isu seperti hak asasi manusia, akses kepada pendidikan dan keadilan sosial akan menjadi tema utama dalam karya-karyaku. Dengan menggunakan warna, bentuk, rentak dan simbol yang kuat, aku berharap dapat menarik perhatian orang ramai dan mengajak mereka untuk merenung tentang realiti yang dihadapi oleh aku dan masyarakatku.

“Aku juga ingin menjalin kerjasama dengan organisasi dan individu yang mempunyai visi yang sama. Melalui pameran seni, bengkel dan projek kolaboratif, aku berharap dapat mencipta platform di mana suara masyarakat stateless dapat disuarakan dengan lebih lantang. Dalam dunia yang sering kali dipenuhi dengan kebisingan, aku ingin menjadi satu suara yang jelas dan tegas, yang mengajak orang ramai untuk melihat dan memahami isu-isu yang dihadapi oleh kami yang terpinggir.

“Selain itu, aku ingin menggunakan media sosial dan platform digital untuk menyebarkan karya-karyaku kepada audiens yang lebih luas. Dengan memanfaatkan teknologi, aku berharap dapat menjangkau lebih ramai orang dan menggalakkan perbincangan tentang isu-isu penting ini. Setiap rekaan yang aku hasilkan bukan hanya sekadar karya seni, tetapi juga satu panggilan untuk bertindak, satu ajakan untuk bersama-sama memperjuangkan hak dan keadilan bagi masyarakatku.

“Harapanku adalah untuk melihat masyarakatku mendapat pengiktirafan dan hak yang sepatutnya, dan aku ingin menjadi sebahagian daripada perubahan itu melalui seni. Dengan visi ini, aku melangkah ke hadapan dengan penuh keyakinan, bertekad untuk menjadikan seni sebagai alat untuk perubahan sosial. Dalam lima tahun akan datang, aku ingin melihat diriku bukan hanya sebagai seorang artis visual dan pemuzik, tetapi sebagai seorang aktivis yang berjuang untuk keadilan dan hak asasi manusia, membawa harapan dan suara kepada masyarakat yang terpinggir.”

In other words,

In five years’ time, I envision myself as a visual artist and a protest lyricist committed to bringing out the voices of marginalised communities through my songs and graphic design works.

I want to be a voice for my community, especially the stateless communities, who are often unheard and face numerous challenges and injustices.

As an artist, I believe that art has the power to change perspectives and raise awareness. In every painting, poster, graphic design and the rhythm and lyrics of my songs, I want to convey stories that have never been heard. Issues such as human rights, access to education and social justice will be the main themes in my works. By using strong colours, shapes, rhythms and symbols, I hope to capture people’s attention and invite them to reflect on the realities faced by me and my community.

I also want to collaborate with organisations and individuals who share the same vision. Through art exhibitions, workshops and collaborative projects, I hope to create a platform where the voices of stateless communities can be heard louder. In a world often filled with noise, I want to be a clear and firm voice, inviting people to see and understand the issues faced by those of us who are marginalised.

Additionally, I want to use social media and digital platforms to spread my work to a wider audience. By leveraging technology, I hope to reach more people and encourage discussions about these important issues. Every design I produce is not just a piece of art but also a call to action, an invitation to join the fight for rights and justice for my community.

My hope is to see my community receive the recognition and rights they deserve, and I want to be part of that change through art. With this vision, I step forward with confidence, determined to make art a tool for social change. In the next five years, I want to see myself not just as a visual artist and musician, but as an activist fighting for justice and human rights, bringing hope and voice to marginalised communities.

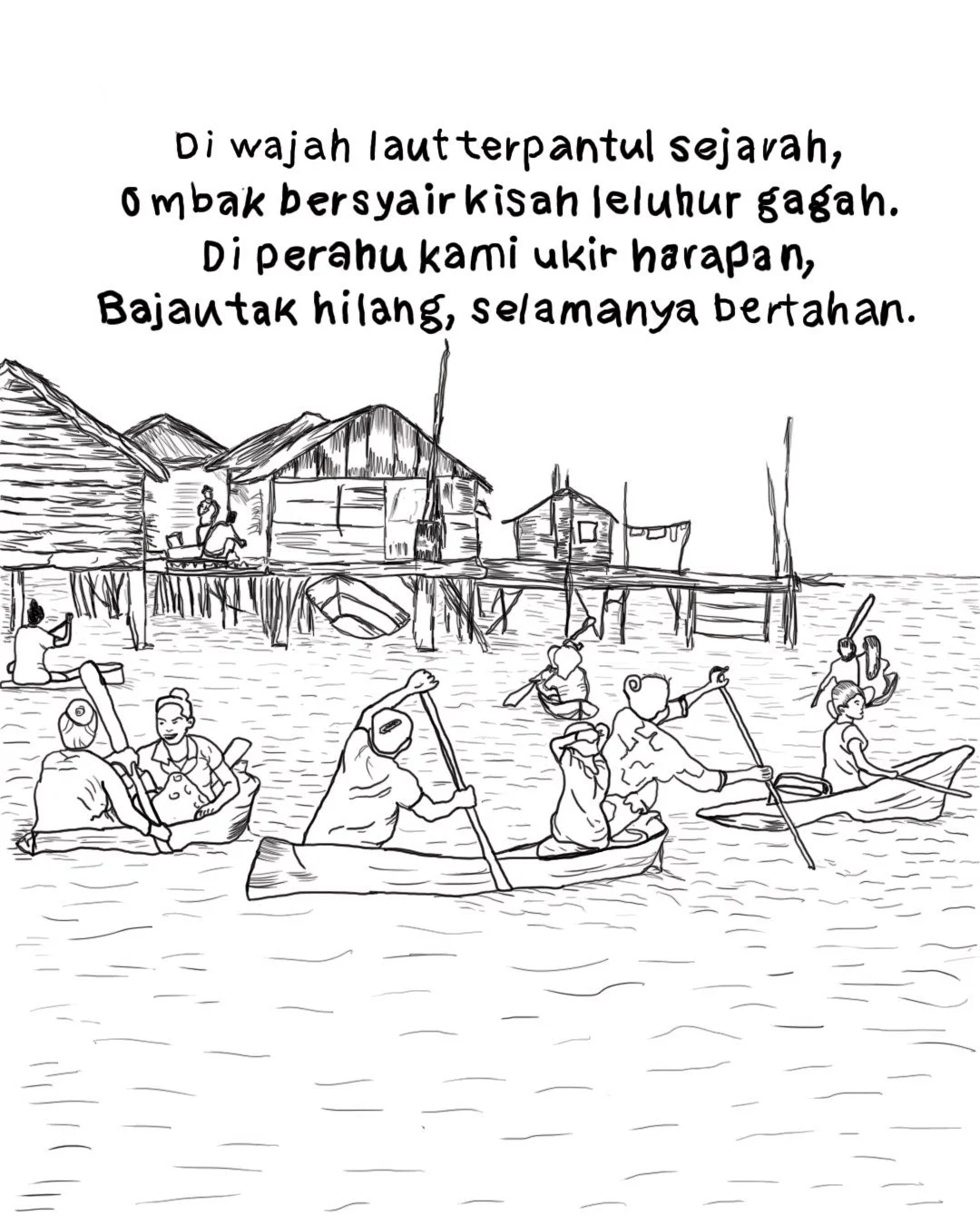

Drop - Busai (2024)

Image description: The image is rendered in fine, black lines against an entirely white background. Human figures are depicted rowing boats on water, individually and in pairs. In the background are wooden kampung houses built on stilts. Above this scene are the words “Di wajah lautterpantul sejarah, ombak bersyair kisah leluhur gagah. Di perahu kami ukir harapan, Bajautak hilang, selamanya bertahan.”

Sometimes, I fear for Drop’s safety. His brazen rebellion and participation in demonstrations make him a prime target for arrest. However Malaysian he is, he is a citizen of nowhere, protected by no laws nor borders nor rights, and especially not the right to lawful trial.

“You not scared ah?” I asked him.

“If tangkap then tangkap lah,” he replied. If I get arrested, then so be it.

After all, what’s the alternative to resistance? To do nothing?

“Dalam perjalanan ini, aku sedar bahawa cabaran pasti akan ada. Namun, dengan semangat dan dedikasi yang tinggi, aku percaya bahawa aku dapat mengatasi segala rintangan.”

In this journey, I believe that challenges will arise. But with great passion and dedication, I believe I can overcome any obstacle.

Erel is a Singaporean university undergraduate aspiring to continue their work with stateless persons and in advocacy following their graduation. Outside of their major in Political Science, Erel hones their creative skills in the subversive and esoteric bits of music and writing, expressing particular frustration with institutionalised systems of injustice. One of these days, Erel hopes to achieve world peace. Anytime now.

Drop is a student from Tawau living in Semporna. He is stateless. He writes poetry and song lyrics, and produces music, protest caricatures and other humanity-themed artworks. The spirit of punk and DIY culture form the basis of his fight to create a new revolution for the stateless community.

“He had, after all, come to this island on a whim. To cut wood down, resurrect it in something lifeless.”