The Different Definitions of Love | এটা অপ্ৰেমৰ গল্প

By Kaushik Ranjan Borah

Translated from the Assamese by Aruni Kashyap

Parismita Singh (in collaboration with Hiyang Yengkhom); Detail from scroll: Mother, I Will Destroy Your Art, 2022. Pen and Ink on rice paper. 20 cm x 140 cm.

Image description: Fine line drawings in black ink of figures and prehistoric creatures in a post-apocalyptic landscape of colorful ink washes in cerulean, orange, yellow, and green.

This is not a love story. This is a story of protest marches and existential crisis, of erasure, of being turned homeless in one’s homeland.

It is almost dawn, and I am exhausted after yet another sleepless night. I try to fight the sleep by vigorously rubbing my half-opened eyes. To make it worse, a gust of cold wind wakes me up; it has entered through the little crack in the window that the blue curtains had failed to cover. The wind is so cold that it pierces my body like thorns, killing my desire to vegetate in bed. I throw aside the blanket. A red dragonfly—fluttering its wings, desperately trying to escape—is trapped in the mass of cobwebs that cover the ceiling fan that hasn’t been used for months since the onset of winter. I am fascinated by the dying dragonfly; I can’t take my eyes off it.

With the toothbrush pressed between my lips, I open the window for a second and pull it towards me by force to make sure it is shut properly. But the cold air that licks my face when I open the window doesn’t feel as terrible this time. Instead, it caresses me on the face as if preparing me for the day’s work. The brown skylarks are chirping under the neem tree. A thin layer of fog covers the world outside. A group of teenage boys and girls are hurrying on the road—perhaps in a hurry to grab a few hours of private coaching before their official school hours begin. And the young professionals? They, too, are hurrying to their workplaces in this busy city. But the middle-aged men and women who are out on their morning walks to reduce their waistlines don’t walk so fast. It is 6:50 am. The morning takes time, but the people are fully awake. There is a reason I have slowed down, lingering on small tasks such as opening and shutting the window, watching a trapped dragonfly, or an unused, unclean fan. It is because I want to forget my story. Usually, stories with love in them change people. But this is not a love story—even though there is love and romance, even though this story has changed my life.

But no—I can’t continue like this. I have work to do. I rush into the kitchen to make myself a cup of tea. Focusing on work will help me forget my story. The kitchen smells disgusting from the rotting rice in an unwashed pressure cooker, the decaying body of a frog or a rat in a corner, and the smell of residual smoke from the stubs I have tossed into the trash can.

The cleaning can wait; I sit at the study table with my tea. I focus on math problems as if they need my immediate attention—not the rotting food and dead rodents. For the last two days, I have tried to solve some problems from Legendre’s Polynomial. I relish my tea, sipping it with my eyes shut, and wonder how I can find a path to those problems: the polynomial problems. The dirty kitchen may wait.

Suddenly, rhythmic slogans from outdoors interrupt me. They slowly become louder and take away the morning's brisk, restless, ordinary, pleasurable stillness.

The people shouting slogans walk on the road. The thick fog greets them. I know what they are demanding: “Jati,” “Mati,” and “Bheti”. The people in the procession want to protect the community (jati), the land (mati), the foundation (bheti) of our culture, and our existence in this little part of the world.

As I walk to the window and glance outside, I push aside all the worries in my mind like poorly tossed threads from a spool. I know the frustration of these people who are worried about losing their existence due to new laws that will grant citizenship based on religion, favoring Hindus over Muslims. The plan was to ensure that this land, inhabited for thousands of years by indigenous people, could now be outnumbered by Hindus—the ruling party believed they would vote for them perennially. I sense the worry of the people who are concerned about losing their first language because most of the Hindus are expected to come from Bangladesh, who would speak a different language, one that had once colonized them. Statehood is granted based on language in India, so being outnumbered by speakers of that language means losing statehood, language, and identity. That’s why this is not a love story.

This has happened before. During the British times, the people in this land were prohibited from using their language. They were forced to learn Bengali and English, conduct work in the Bengali language imposed on our ancestors, and study in that language in schools and colleges. The people have not forgotten those days. Their generational anxiety of losing their land and culture, their anxiety of not being able to speak in their tongue, float in the air and enter my room through the window:

“Must meet our demands!”

“We will not accept the Citizenship Amendment Act.”

“Joi Aai Asom!”

“Hail Mother Assam!!”

Parismita Singh (in collaboration with Hiyang Yengkhom): Detail from scroll: Mother, I Will Destroy Your Art, 2022. Pen and Ink on rice paper. 20 cm x 140 cm.

Image description: Fine line drawings in black ink of women working and cooking in a post-apocalyptic landscape of colorful ink washes in predominatly orange with details in cerulean, yellow, and green.

*

I am helpless in front of the slogans as they trigger memories from a past I have failed to forget. Like the red dragonfly, the incomplete math problem twitches and suffers on the empty page of the notebook. Whenever I come across these people, these slogans, I start suffering like a trapped dragonfly. Across the window, on the road, the protest march continues to move with increasingly agitated slogans.

Around fifty people sit in a circle, blocking the bus and the main road in the city. A group of busy men and women look at the protestors with annoyance. I don’t like that the sound of vehicles, the chatter of people, and horns, slowly drown out the slogans. I want the slogans to be heard.

Around three months ago—sometime during December 2019—the protests that began in this city started spreading into the state's smaller towns like wildfire. The students, too, jumped into the protest movement as soon as they finished their final exams. The main roads of the city soon smelled only of smoke and burnt rubber. Burning tires are used to barricade the main roads, and the skies are pierced daily by the slogans:

“Joi Aai Asom!”

“Joi Aai Asom!”

The people on the road shout forcefully. Even I join them, in the same tone, with the same energy and determination: “Joi Aai Asom!

Today’s protests are a bit low in energy, but the December Protests were not so pale; the voices of the people were also not so calm. What was it that made the protests three months ago so fierce? Was it anger? Or the fear of being turned homeless? Disappointment with the government?

*

I try to reimagine those days…

I hold Nobarun’s hand; everything is so passionate and exciting. Here, we are roaming around the strange lanes of the city: Pragati Path, Rupohi Ali, Rajbahor Bylane, etc. There, on the terrace of my rented house, we are sharing a cup of tea just before sunset.

We are sitting on the terrace with a bottle of Old Monk. A lovely, nippy wind gives us company; not cold, not hot.

“Do you need to sport this beard? It looks so uncouth.” I take a sip of the cheap rum and tell Nobarun. My eyes feign irritation and anger.

“Ah, now your biggest problem is with my beard, when you should be worrying about the abnormal dip in the country’s GDP, in the increase in gas prices. Worry about my beard when things calm down.” Nobarun is joking. He chews peanuts from the plate with his drink.

There is a power outage. He looks at the city swallowed by the darkness from the terrace and says, “The darkness is better than the light. In the darkness, everything is equal. No one has color in the darkness. Nothing has color.” Then he goes eerily quiet.

“Darkness means black. Black absorbs all color.” I utter the sentence and regret it. What am I saying? I should say something clever. I want to appear intelligent in front of him.

But Nobarun remains quiet for a while and then speaks, “Anindya! The black color doesn’t mean darkness. Where there is nothing, there is the color black. Black means zero, and from zero, life begins. Zero means possibilities. One day, everything had begun from zero. In the black color, there is Lord Shiva, the god of dark-skinned people like us.”

He is speaking like a seasoned philosopher. Occasionally, he pauses because he is so drunk.

“If everything is present in black, what about the color red?” I am teasing him. I want to entangle him in his web of words, so I ask random questions. I like to have fun at his expense.

“Ah, the red color is the color of the soul, you know! The color of blood! The color of revolution! Our lives begin in red and end in red!” He is quick to reply.

As he speaks, a car passes through the road. The headlights fall on his face, and I find his bearded face even more handsome than before. But he looks hotter without a beard.

The power returns when we are sipping our third glass of rum. The city is now covered in light. Everything is visible, and taking a deep drag at the cigarette, I watch him. He is six feet tall. His muscled body is so attractive. When he finds me staring at his face for too long, he holds my shoulders with his two hands, shakes me back to reality, and laughs loudly. I can’t stop laughing too. We burst out in prolonged, intimate laughter.

The evening feels romantic. The fairy lights on the terrace's railing make it even more intimate and mysterious because there is only a little light. In a half-awake, half-asleep state sloshed in alcohol, he walks toward the large empty canvas and starts painting. I bring the colors and the palette, stand behind him, and watch him fill the canvas with his easel. He paints, taking occasional drags from his cigarette.

Two male figures. They are well-toned and ripped like Greek sculptures. Together, they hold a rainbow.

Once he finishes the painting, he drinks the last glass of rum and sleeps with his head on my lap. I caress his long beard and watch him. I watch the empty tubes of colors and whisper into his ears, “See, see! These colors are so beautiful. They are so good. They are genderless, religionless, and without any nationality. Colors are just colors.”

Nobarun wakes up, “I wish we could be like these colors. I would have tried to build a colorless, religionless, nationality-less society.”

His eyes are still half open. I kiss his forehead warmly and lie down next to him. The cold floor is the only witness to our dreams for a genderless world.

Parismita Singh: Detail: After the Plague, 2023. Pen and ink with digital fonts. From a graphic novel; previously published in: Old Stacks, New Leaves: The Arts of the Book in South Asia, edited by Sonal Khullar (University of Washington Press 2023).

Image description: Section of a fine line drawing in black ink on white ground showing a ragged figure dragging a small ramshacle boat through a post-apocalyptic landscape.

*

I hear a commotion on the road. More people have gathered. No, these protests have lost their intensity. They don’t have the power to inspire and move as they were able to move us three months ago. There are no burning tires on the road that used to give the marches heat and passion and sinister quality. There is something too ordinary and belabored in the protests now.

And why not? Everything had come to a standstill when the protests started: the shops had shut, the railway tracks were blocked, and the roads were empty because people refused to venture out and go to work. But now, cars are on the road, offices have reopened, and colleges have organized examinations and make-up classes. On the one hand, protests are going on, but state-sponsored so-called peace processions are also seen around, rendering the anti-government protests meaningless. And what about the big dams that are going to displace thousands? The activists brought the construction to a standstill during the heat of the movement. The river is slowly being killed again as the extensive dam construction progresses. Everything is back to normal, but the reasons why the agitation started have remained unsolved, unheard, and unconsoled. No one has the time to think about those men who are in prison, moaning in pain, hoping to be rereleased.

I am imprisoned in my emotions; I cannot venture into the world outside, with fresh air and no smell of rotting rice and reptiles.

Right. Nobarun was right. He had predicted that the intensity would fade and everything would return to normal. Those evenings—intoxicated by curfew and that smell of smoke and fire, are no more. These regular, non-curfewed sober evenings are colorful. Yet when the world has come to embrace this normalcy, I have failed to do so. I have changed forever.

This is not a love story, but this is the story of Nobarun.

I kneel and drag out a box of paintings by Nobarun. There is a thin film of dust over the canvases. No one has touched them in three months. I spread them on the floor one by one, and a familiar smell starts to mix with the repelling ones in my room.

I met Nobarun at an art exhibition. My college friend Animesh is also a painter, and he asked me to drop by Kala Bhavan to view some paintings. At the end of the exhibition, Animesh introduced me to a bearded young man with unkempt hair. He looked around my age.

“This is Nobarun. He paints very well,” Animesh told me.

“So, are you an artist?” I asked him after some small talk.

“No, I am an engineer, but sometimes I paint.” His eyes were dancing, full of mischief. I couldn’t help but stare.

And that was it: following that conversation, we could not help but meet each other repeatedly, becoming closer after every meeting. Soon, I stepped into a world that was so different from the world I had lived in thus far. A world of colors, love, and stories with no gender.

No, I can’t keep on looking at his paintings. I must solve the math equation. I fold them with a heavy heart and return to my desk, to the world of Legendre’s Polynomials, but Nobarun is everywhere in my room. As I turn the pages, a tissue paper falls out with my Nobarun’s handwriting. My Nobarun! Such beautiful handwriting!

Parismita Singh: Detail: The Fox Wedding (or, The Gods No Longer Hear Us), 2022. Pen and ink on paper, 167 cm x 274 cm.

Image description: Section of a fine line drawing in black ink on white ground showing a porcupine-like creature emerging from a vase with geometrical designs, falling through tumultuous skies of stylized clouds, falling objects, and a banana tree leaf.

*

The night before Nobarun visits his village, we attend a demonstration where everyone holds a torch. The torches are made of clothes tightly wrapped around the tip of wooden clubs and dipped in kerosene before they were lit. Thousands of young, college-going, middle-aged people spontaneously walk peacefully on the streets to register their angst against the law. No union is leading this spontaneous protest. People are just coming out of their houses with torches on their own. I have never witnessed such an incredible scene.

I walk with Nobarun and notice a ten-year-old boy and then, a bit later, a few octogenarians with walking sticks in one hand and the burning torch in another. I see Ramdhon, the local vendor who sells vegetables in retail by the pavement, and the fish seller Dinesh, who also goes door to door offering his daily catch. My neighbor, Dr. Baishya, is also here. There is anger and frustration. But there is also hope that something will come out of this. Something positive and constructive.

People shouted together, like a chorus: If you are an Assamese, do not give this a miss!

“When the matter is about our motherland, who needs a command?”

“Hail, Mother Assam!”

As we walk, the spectators on the footpath first watch the people in the rally and then join us. The people returning home with shopping bags also join us instead of returning home. There is a gradual, steady increase in the number of people who join. I see the anger and hurt of being taken for a ride in the expressions of these people. We also sing songs. We pull up our sleeves, walk, and sing songs about our homeland. Nobarun’s torch is burning so bright. He reminds me of a horse on a battlefield: determined and energetic. I take out my smartphone and click a photo in secret. He looks so good. Then I shout, “Oh, My Country, Why Do you Force Us to Be Rebels?”

That night, the city is enveloped in a smell of burnt clothes and kerosene. The smell floats over the city along with a film of smoke, lingering like the echoes of the people on the streets.

After a while, we leave the rally. We are hungry since we have been walking for a long time. We hold hands as we walk into a restaurant with an ajar door. The people stare at us quietly: two men holding hands. The smell of potato chips, fried rice, and sauteed chowmein on a wok waft through the restaurant. There are a lot of people inside. They are all talking; their choric, mild hum replicates the sound of a beehive. They look at us repeatedly.

We sit next to a table where a few customers talk about the movement. A few men look angry. One says that the state government has sent a memo asking employees to avoid the marches. They are angry about it. They scold the government, accusing them of being greedy and trading the more significant cause for small, short-term political gains.

We rush to finish our noodles and order coffee with cream and sugar. The coffee is hot. Its vapor touches our eyes and faces. Nobarun is holding my right hand in a firm grip.

And I? I am staring at his face constantly. The coffee is so hot. I see that his eyes are watery. He is leaving for home tomorrow for ten days. I am staying here. I cannot imagine spending that time without him. His grip suggests that he knows that.

The people cursing the government and discussing the protest now divert their attention to us. They find our intimacy strange. They find the intense chemistry between us odd, and they stare more. I can feel their eyes crawling over the two of us: their gaze on his hand, which is on my right hand, a firm grip. He is rubbing and massaging my right hand. Fast, slow.

He brings out a piece of paper napkin. I find it hard to read because my eyes are watery. What is Love? It starts with a spark between two pairs of eyes, but at the end, it leaves the heart wounded.

My heart melts like a candle next to the fire. Surprising everyone staring at us, he leans over and kisses my lips. The people are shocked. They look at us with hostility and disgust.

But later, when he spent the night at my rented accommodation, we didn’t talk about love. We talk about the land and its people. We talk about the betrayals of people who have power. He tells me that the Act would affect our state differently. I know these things. But I listen. I like it when he starts criticizing the failed mass movement in the 80s. Who was responsible for its failure? He asks in anger. He answers his question—just because of a few leaders whom our people trusted but later realized had no spine in front of the federal government. Was there any other reason? He asks. That was a significant movement, right? Its history is written with blood, he says.

As the night progresses, we try to find answers to our questions. We smoke cigarette after cigarette and discuss the writings of Parag Kumar Das—the rebellious journalist who was shot dead in broad daylight: could we be an independent economy, leaving India? How about the rebels whom our people supported, hoping we could get rid of India and form a different country? We dissect. We analyze. We mourn the people who were tortured in the eighties in the name of counter-insurgency operations. We have bad leaders, we agree. We have leaders who cheat us, we agree. And in the end, then people suffer. We agree on that, too.

Later, Nobarun becomes a little impatient. He gets upset thinking about Irom Sharmila, who has been fasting against inhuman government laws such as AFSPA for 16 years; the government charged her with attempting suicide, and a judge commanded that she be force-fed. He becomes emotional thinking about Gauri Lakesh, the writer who was shot dead for critiquing Hindu fundamentalism. I am amazed by his depth of knowledge, passion, and insights. I stare at him as he speaks.

I cook mutton-leg soup for us. We have it with some rice and open the laptop to watch a series on Prime Videos called Made in Heaven. We have been watching it together. Only a few episodes are left. We binge-watch.

Gradually, one of his unruly hands starts to roam around my body. I hug him hard, bringing him closer. His lips press themselves on every part of my body. We find ourselves sweating heavily that December night.

When he leaves early in the morning, when most people are still asleep because of the curfew. He boards the government bus; the golden sun brightens his face. When he reaches home, he is greeted by another rally in his village. I know this because he sends me a photo of the crowd, the march. Some of the photos feature him. He is speaking. He is raising his fist. He is leading, and I again fall in love with him.

Dying to hear his voice, I rang him the following day. “The number you have dialed is switched off or out of network coverage! Please try after some time,” a metallic voice tells me.

This is normal. The reception is poor in that area. His village is mottled with tall bamboo plants. I often tease him, “Oh, you live in the middle of nowhere in the forest of bamboo; no wonder there is no reception in your village!” He never takes it to heart, but laughs at my mocking sentence. This has never registered to me as something to be worried about.

But this time, I am, because the protests and the blockades intensify as the days pass. The colleges shut down. The school-going children are asked not to attend. I am inside my locked single-room apartment for days because it is unsafe to venture outside. I miss Nobarun incredibly. His phone remains unconnected.

I leave messages, but he doesn’t call me back. The messages are not delivered. My anxiety starts to gallop. How can my mind not race during these days when dangerous fires are blooming everywhere, from villages to small towns? I spend the night under stress. His father informs me in the morning that yesterday, the police had picked Nobarun up. I gasp, unable to accept the news. I am unable to stay in the city anymore.

The political events worsen as I leave for his village on my motorbike. The bill that the people had been protesting for weeks is passed with a two-thirds majority in the parliament—far away from those who had been protesting it. The government has installed phone network jammers to quiet our voices and block internet services throughout the state. The forever busy city’s buildings are on fire as I ride out of it.

It is four hundred and fifty-three kilometers from his house. On the way, I ride across burning villages, people running helter-skelter, protesting. How is Nobarun? I hope the police don’t torture him. I keep an eye out for gas stations. Some say dissenters do not attack hospitals and emergency services such as pharmacies and gas stations. But still, most of them are shut. I don’t want to be stranded without gas, so I obsessively refill whenever possible. Some mom-and-pop stores are open, and I stop by briefly for a snack or a cup of tea to remain awake. I need all the energy.

Finally, I stand in the courtyard of my future father-in-law and mother-in-law. Even though I am exhausted by the long ride and traumatized by what I have seen, I can’t stop imagining that this is my first time at my ‘in-laws.’ Can I call them in-laws yet? They are like my in-laws, the parents of the man I love! I am amused when the thought comes to my mind, despite my tiredness. I smile and walk through their gates and the small betel-nut tree covered lane that leads to their large courtyard.

My in-laws’ house has an austere look to it. Its walls combine three-foot-high brick walls from the ground, which props up wooden walls covered with loamy soil. A coat of greenish limestone covers the soil plaster. The combination wall is further held together by wooden planks arranged in squares. It is an old house, but it is severe and sturdy. I have seen this house before in photos.

I see a group of people in the vast courtyard, and my smile vanishes. I don’t see a single familiar person. I had met his parents before when they had come to the city.

In the corner of the large veranda, there is a wooden chair. Nobarun’s father is sitting there. He looks upset. His eyes are red. He is surprised to see me, and almost jumps up.

“I am Anidya!” I tell his father.

“Yes, I know,” he said. “Go in; they have sent him home.”

I almost run, pushing aside the group of people. Nobarun is sleeping. There is a bandage around his head. Dressing over his hands. His bright eyes have sunken in. Dried blood stains his face. Ah, I am not able to watch him in this way. Gently, I rub his forehead with my hand. He wakes up, startled, a pale smile on his face.

It is a cloudy day, the room dark. The people outside hum like bees.

Nobarun’s grandmother enters the room, pushing aside the dark green curtain on his bedroom door. “Have you seen? How they have tortured my boy, my punakon! I told him so many times to stay indoors, that times were not good, but he wouldn’t listen. What was the point of joining those boys who got him into trouble?” She is talking about the protestors. But every young student has taken to the streets. His father was no different when he was young. He had to remain underground for long stretches due to his work with the student union during the eighties. His father’s father took part in the independence movement against the British. And now that man’s grandson behaves the same way, only times have changed! “Those days were different! Those were British people; they had to leave. What foreigners are you all after now? Who are you trying to drive out of the county? They are all our people; we all look the same! Mahatma Gandhi has done everything for the country; he sacrificed himself. Don’t we have enough sacrifices?”

She starts to weep, but I am unable to speak. She is in her eighties and a bit incoherent. I don’t have the experience and language to console her. I do not have the heart to tell her that this is not Gandhi’s India. The promise of independence has not been fulfilled in more than seventy years. Gandhi is an old, demonetized coin now. In today’s India, the rulers have constructed a temple to worship the person who murdered Gandhi. Should I tell her? Should I not?

Nobarun tells her, “Aaita, why don’t you go to speak to my mother? I will explain everything to you when I am better.”

I watch her leave. Her walking stick makes a khat-khat sound on the hard floor. His grandmother is illiterate, but her questions are legitimate. She didn’t have to go to a university to ask those fundamental questions. Why do we need to protest? Who are we protesting? Why do we have to protest the government that is supposed to protect us?

When it is evening, the crickets start to sing. I sit with Nobarun’s father next to a fire and chat about the news we have heard from people we know. The internet remains banned, and phone networks are absent. So, we rely on relayed news. News that brings stories of a state on fire. We hear about the death of five young students. We call them martyrs. Nobarun’s father expresses his frustration with the failed promises of independence and the failed movement of the eighties. Switching back to the present day, he says nothing has changed and cites the example of a popular farmers’ leader who was framed by the state and charged with sedition for demanding the rights of poor people. The emotions are the same. The fundamental political problems are the same. The time is different. The situations are different. The characters are of a new generation.

Roshmita, Nobarun’s younger sister, sits beside us. She has brought a few cups of hot tea from the kitchen. Just like Nobarun, she has a sharpness in her tone, and her insights about society and the state are precise. She talks about an article published in Prantik magazine and expresses worries about the growth of religious tension under the current regime. The Cow is now a political animal, she quips. She adds that there is a divide-and-rule policy like the British rule. I try to see society through her eyes. She is almost six years younger than us. Did we worry about these things six years ago?

We have finished the tea. The stories of cows and politics and Hindus and Muslims and the eighties are over. The fire has turned into embers. Nobarun and I go for a walk. In the village, among the tired people returning from day-long work in the fields, I smell sweat and exhaustion. Most others, the farmers, are asleep after wrapping up fieldwork for the day. Their day begins very early. Only a few things break the silence of that late evening that feels like midnight: the howl of distant foxes and the sound of dialogues from soap opera on the television. A mysterious silence rules the village, and even though it is pitch dark, even though I want to, I don’t hold his hands. Things are different in the city and on the university campus. Here, we can’t be at ease.

“It is hurting, right?” I ask about his wounds.

“Aren’t you hurting too?” He asks. “Otherwise, you wouldn’t turn up like this so suddenly.”

We both laugh at each other’s questions.

“You know, the agitation has spread into the deep recesses of the village as we had expected. But politics is so dirty. People are already feeling trapped and directionless.”

I nod my head.

“Did you bring any smoke?”

I hand him a cigarette. “Being the teacher’s son in a small village is so hard. To maintain his dignity among the public, I can’t even do the immoral deed of smoking a cigarette. He would die of embarrassment.”

I don’t have a family. Raised in an orphanage, I don’t understand these things, or maybe I have never had to worry about these things. And now, for me, Nobarun is everything. My family. My world. A large banyan tree that gives me shade.

We let the evening float away in cigarette smoke and returned to his house. I whisper in his ears, “How about I ask your father for your hand?” He gives me a quizzical look and laughs.

After dinner, we lie down on his large double bed. I am tired after the long journey, so I fall asleep soon, but his touch wakes me up after a while. Nobarun! Ah, Nobarun! Unable to contain his happiness, he presses his lips on my cheeks, hugs me tight, and climbs over me. I wrap my hands and legs around his body, and perhaps because he is worried about us making noise, he presses his lips on mine with force, not letting me make even the faintest of sounds. I run my fingers across his body. One after another, warm kisses on each of his wounds. He moans, and I recognize it because it isn’t the moan of pleasure. He is in so much physical pain. In a while, when the night deepens, we take off all our clothes and explore each other. We go deep into each other’s bodies.

I don’t remember what happened after that. A huge scream wakes me up. It is morning, and Roshmita has let out a huge cry. She is in the room to wake us up and offer cups of tea. She looks as if she has seen two ghosts. A crowd gathers before we can do anything: his father and mother. His retired father would die of embarrassment if someone reported his son as a smoker, and how about this? His father walks toward us and slaps Nobarun. Then he looks at me, “Get out.” Her grandmother has also reached, following the noise and the commotion. She has the expression of a confused little child.

I am so paralyzed by shame and pain that I can’t speak up. Nobarun is behaving like someone who has been struck by lightning. He is sitting on the bed, shaking, because he doesn’t want to be the cause of his father’s stolen dignity.

I sneak a glance at Nobarun’s father’s eyes. They are like two flames. His mother is no longer in the scene. She has left, but I hear a woman weeping in pain. Or perhaps it is his sister. Or no, his mother. Is that his mother? Is it Roshmita?

The abruptness of the awkward and terrifying situation doesn’t let me make well-thought-out decisions. We are both paralyzed and directionless—just like the movement that has now lost steam and direction after three months.

Taking slow steps, I walk to my motorbike, my backpack hanging from my shoulder. Inside is a bottle of Antiquity Blue whiskey. I didn’t even get a chance to open it. After riding aimlessly, I stop at the edge of their village—more than four hundred kilometers away from my city. I start drinking the whiskey until the bottle is empty. I throw up on a tree trunk near the road. A group of protestors walk past me. They stare at my face, at the empty whiskey bottle, and whisper amongst themselves. They watch me again after pausing their slogans.

When I reach my city, it is evening. The roads on both sides of the city are still burning. There is devastation all around, but the internet ban has been lifted. People stop worrying about the future of their community and shift their worries to themselves and their lives, exchanging gossip and news. I do not get any news about Nobarun that night. I don’t get to know for a while that as the city is taking a turn towards some change, Nobarun’s body is found hanging from the branch of a neem tree behind his house.

He has shamed his father. This was his way of saving his father’s dignity. When this happens, I am still riding into the city. Business establishments are burning on both sides, but as the internet connects people in its invisible web, in the smoky air, our story starts to float through instant messaging apps and social media. Our friends get to know us. People I don’t know, people who worry about the future of our community, and people who talk about indigeneity and discuss constitutional rights, suddenly find something spicier to gossip about. They no longer discuss state-sponsored violence and worry about the community but discuss our love story that has ended in misfortune and tragedy. But no one talked about the schoolteacher’s dignity and how to keep that dignity intact. A young man whose eyes had witnessed only twenty springs had to hang himself. I wouldn’t know about this yet; I come home and sleep. Exhausted, pained; no knowledge that Nobarun is gone.

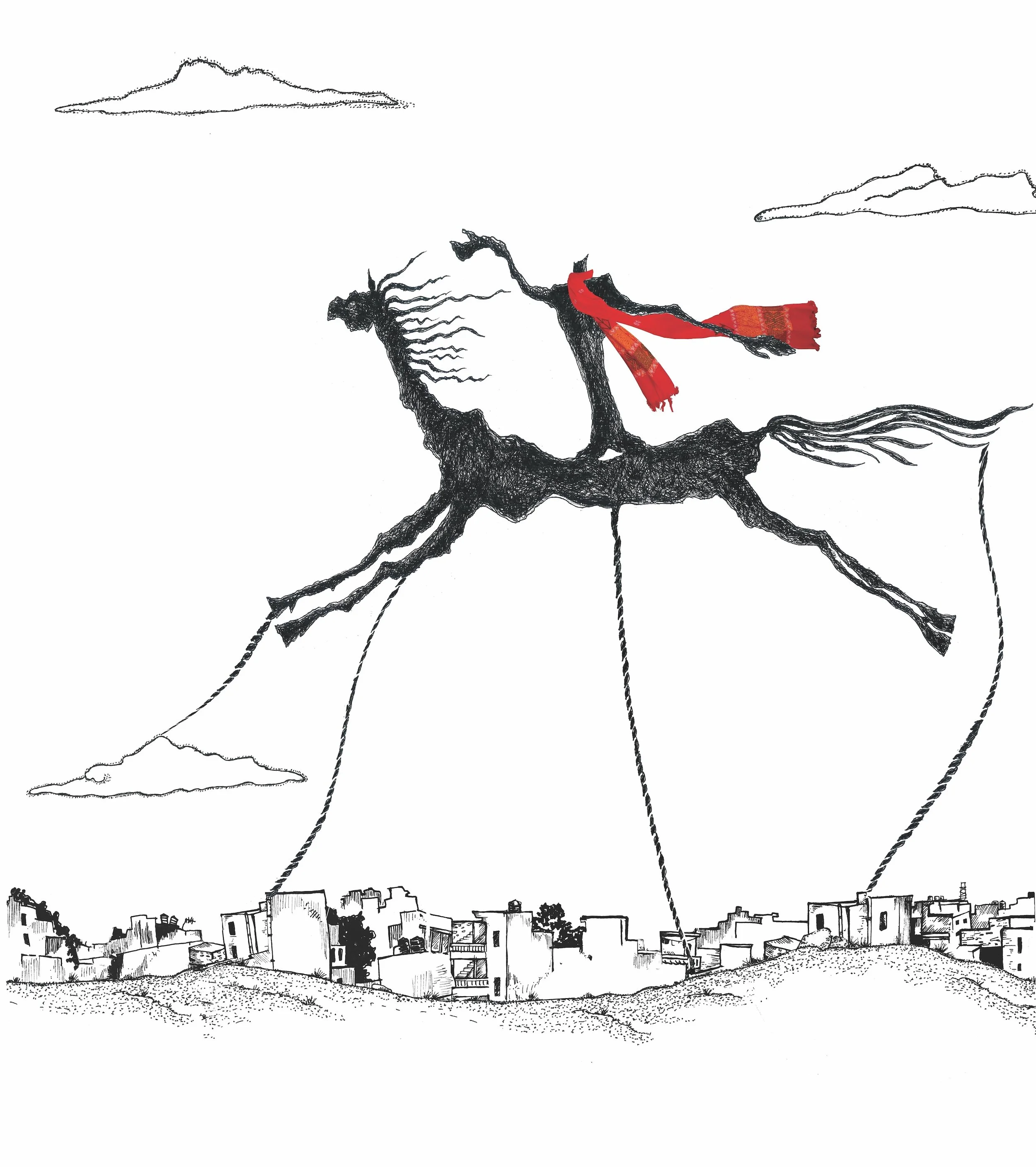

Parismita Singh: The Headless Horseman, 2015. Pen and ink with digital collage.

Image description: Fine line drawing in black ink on white ground of a stylized horse and headless horseman floating above a city like a hot air balloon and held by ropes. The horseman wears a red scarf.

*

A lot of time has passed since then. I have graduated. I now work for a small private college that doesn’t offer undergraduate degrees. I drag myself to class to stand in front of the students daily to keep my job. The stories from my past, my love story, continue to haunt me. Recently, my colleagues have found out about it, and they hum and murmur like bees, like those people in that restaurant in front of whom Nobarun had kissed my lips…

There are so many things Nobarun and I wanted to do. Wait for the warmth of June and walk during the pride march in our city, holding hands; finish weaving that dream for a genderless world. But no, nothing is possible in his absence now; the dream threads have entangled, matted.

It hurts so much to be unable to hold that hand anymore; the hand I had imagined I was gripping for life. During those rare, good moments, I think about his hand, which used to give me courage when I lacked it. I wake up often in the middle of the night, startled, looking for Nobarun. I only sense emptiness. There is no one around me to tell me or listen to stories of color, stories of a genderless world. Instead of those stories, my memories float to me like distant melodies of lullabies to console me like a child. The notations of those consoling songs are as if written on the pages of an invisible diary.

I hold the piece of paper where he wrote his poems. His smell is as if intact in the creases of that paper. I kiss it, smell it, rub it against my face, and stare at it.

What is Love?

What is Love?

Starts with a spark between two pairs of eyes, but at the end, it leaves the heart wounded.

I hold the crumpled old paper for a long and murmur his lines.

What is love? A corroded, wounded heart? Or is love Lord Krishna’s girlfriend Radha’s pain—she who weeps at the other bank of the Yamuna, waiting for him? What is love? Is it embodied by the Taj Mahal that Shahjahan had built for Mumtaz? Or is it a cobweb that traps red dragonflies?

Another sleepless night begins. I am not worried about the cold. Standing in front of the open window, I watch the world over which an overcast sky is hanging, and a sad, sorrowful breeze is blowing, carrying the cries of people who may become homeless in their homeland. How could this be a love story? This is not about Nobarun or me.

Kaushik Ranjan Bora is a graduate student at the Department of Physics, Dibrugarh University, India. His short stories have appeared in a range of publications, such as Satsori, Prakash, and the anthology Selected Assamese Queer Fiction (Students House Press, 2022).

Aruni Kashyap is the author of The House with a Thousand Stories (Penguin 2013), His Father’s Disease: Stories (Gaudy Boy Press 2024), editor of How to Tell the Story of an Insurgency (HarperCollins 2020), and the poetry collection There is No Good Time for Bad News (Future Cycle Press 2021). A Harvard Radcliffe Fellow, National Endowment for the Arts Fellow 2023, he has written for peer-reviewed journals such as Comparative Literature and literary magazines such as LitHub, Catapult, Electric Literature, Kenyon Review, and The New York Times. An Associate Professor of English, he is the Director of the Creative Writing Program at the University of Georgia.

*

Parismita Singh is a writer and artist based in Assam, India. She is the author of the collection of short stories Peace Has Come (Context 2023) and the graphic novel Hotel at the End of the World (Penguin India 2009). Her children’s books include the graphic novel Mara and the Clay Cows (Tulika 2015) and Fat King Thin Dog (Pratham Books 2018). She edited the anthology Centrepiece: New Writing and Art from Northeast India (Zubaan 2018) and helped conceptualise Pao, a collection of comics (Penguin India (2012). Her other publications include graphic reportage series, The NRC Sketchbook (2018-19), and an illustrated column on craft and culture for Voice of Fashion.

In a short story by Yu Xi, translated by Ng Zheng Wei, a gnawing hunger consumes everything.