The People of Santa Claus Lane

by Diane Josefowicz

Review of Lurkers by Sandi Tan (Soho Press, 2021)

Teresa Eng - Lotus (2017), China Dream, Chromogenic print.

Image description: A cyan-coloured pond with several lotus pads floating on the water's surface. At the top of the pond, the upside-down reflection of a couple of beige houses can be seen.

Lurkers, the second novel by writer-director Sandi Tan, opens in the middle of nowhere twice-removed—or, more precisely, on the virtual boardwalk of a beach town in a video game. At the controls is Kee Hyun Park, a sixty-year-old Korean immigrant whose suicide at the end of the novel’s first chapter threatens to bankrupt his shocked and bereft family. When his daughters, Rosemary and Mira, take the family’s ruined finances into their own hands, their schemes ripple through their Los Angeles neighborhood. One by one, their solitary neighbors reveal themselves to be longing for community; almost everyone is waiting for someone else to mount the front steps, ring the doorbell, and ask to borrow a cup of sugar or an extension cord.

The Parks and their neighbors live on Santa Claus Lane in Alta Vista—a place that, if I’m not mistaken, is a fictionalized amalgam of Pasadena and neighboring Altadena, with the same wide boulevards and enclaves of Craftsman houses tucked into nooks and crannies of the San Gabriel mountains. By opening the novel inside a video game that is itself being played by a man in a fictional neighborhood, Tan pulls off a neat trick, nesting two virtual realities while making constant reference to a third, real one. But this is only Tan’s opening gambit in a wildly inventive novel about what makes a neighborhood for those who live there.

There are, for instance, grievances held in common. One of the Park family’s neighbors blasts Christina Aguilera’s Stripped for hours every day starting at 4 pm, irritating everyone within earshot. A beater car resting on concrete blocks is another source of communal resentment. Not even the breathtaking natural beauty of the mountains is enough to offset the general malaise. Driving up into the neighborhood from the valley below, the narrator reports that the San Gabriels “loomed purple and heathery [...] as they ascended Lake,” a fictionalized version of the broad street that cuts through Pasadena before heading into the hills to stop short at a trailhead; in Lurkers, the street figures as a melancholy road to nowhere, an “avenue that ran straight up and up until it lost conviction at the base of the mountains.”

There is paradox at the heart of the suburbs: No one who enjoys living in widely separated and self-contained houses surrounded by lawns, with no sidewalks or walkable destinations to speak of, is a likely candidate for neighbor-of-the-year. A place where everyone is alienated from the possibility of community is unlikely to thrum with residents organizing fun block parties, never mind societies of mutual aid. What matters is curb appeal, the quality of the home’s exterior, including its landscaping, a special preoccupation in the desert climate of LA. “Summer was murder on the lawns of Alta Vista,” Tan’s narrator declares. “The San Gabriel Mountains held the July air down in a valley chokehold and the parched grass went from green to white to gray to brown in a single breath.” The outrageousness of this particular pathetic fallacy—as if a lawn growing in a desert were an individual with a right to life and not a shockingly wasteful defiance of the reality that water shortages endanger the lives of actual humans—only renders it more fallacious and pathetic. Not surprisingly for the people of Santa Claus Lane, “who took the heat personally,” their solutions are also deeply individualistic:

They either kept longer hours at air-conditioned offices or hid in their homes until night made it safe to breathe again. As the sun went down, the rattle and hiss of lawn sprinklers covered up the whines of rash-covered infants and the whimpers of sunbaked pets. There were no evening soirees organized around cold drinks to commiserate—everybody withdrew.

That such a closed-off enclave should exist in bustling, diverse, polyglot Los Angeles—a sprawling metropolis of nearly four million, many of whom are immigrants, and who altogether speak more than two hundred languages—is one of the novel’s several delicious ironies. Here’s another: the suburbs are all the same no matter how diverse their circumstances and inhabitants. One of the novel’s secondary characters, a transplant from Des Moines by way of a Bay Area commune, moves to Alta Vista with her daughter, adopted through a questionable process from Vietnam in the early 1970s. This young mother is searching for “the real America,” but what she wants is Des Moines all over again, minus the stifling squareness she remembers. Her daughter, Kate, becomes “a teenager of few words” who gets as far as Pomona—a college across town—before a similar homesickness kicks in. Another irony: If everyone hates the suburbs so much, why are they constantly called back? And so Kate returns to Santa Claus Lane, just in time to get embroiled in the Parks’ unfolding drama.

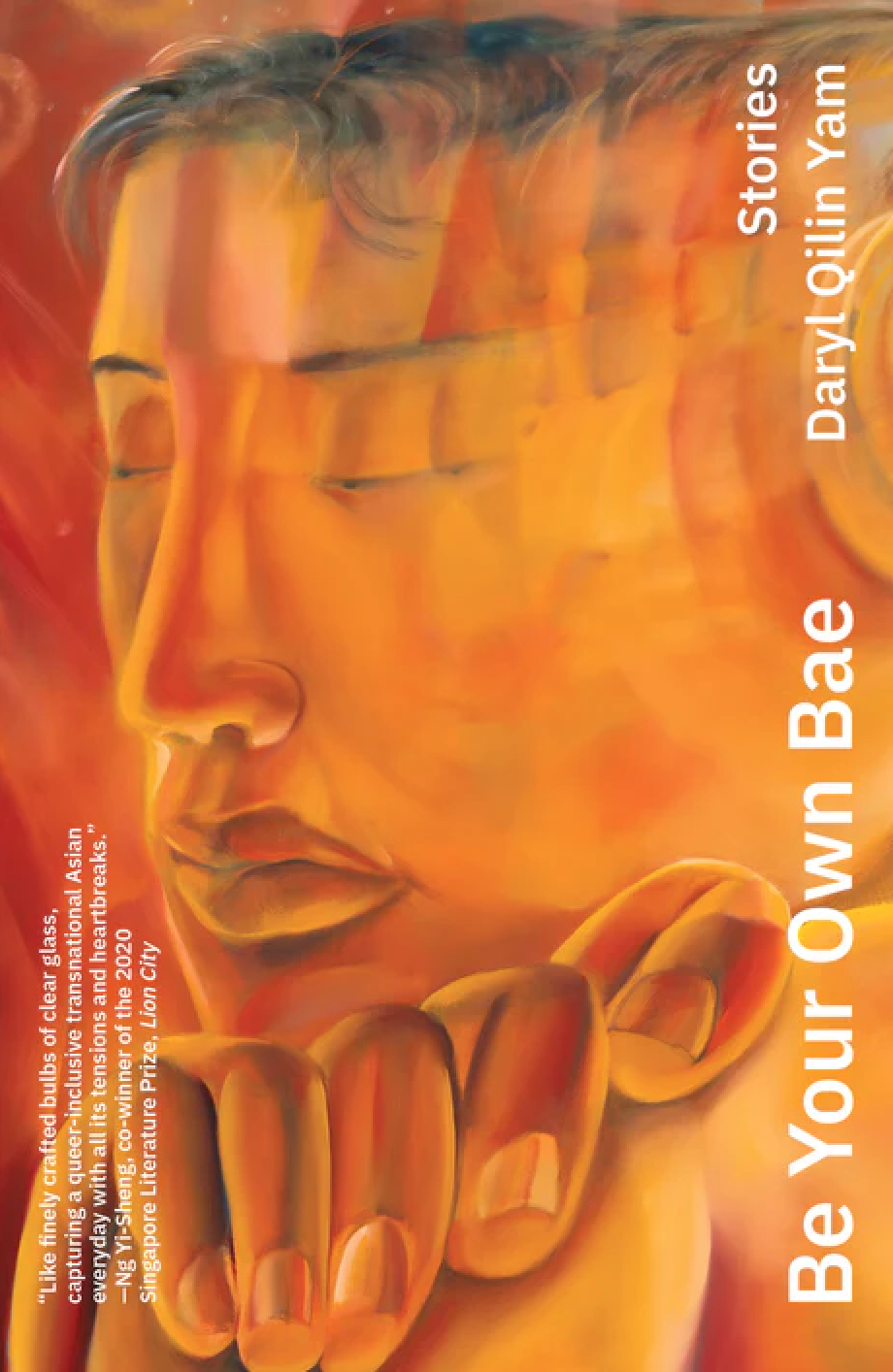

Teresa Eng - Lockdown (2020), Elephant, Chromogenic print.

Image description: A close-up view of a couple of red-brick townhouses with white windows. The image is dimly lit, and the giant shadow of a nearby tree covers the wall of the house’s exterior.

Speaking of drama: the novel’s plot unfolds around one particular neighbor, a white male theater teacher who cultivates a manipulative and intrusive relationship with Rosemary, who has the misfortune of being his student. In this way, the novel evokes Susan Choi’s Trust Exercise (2019). The linkage seems self-conscious and intentional (even the books’ covers are similar); as an admirer of Choi’s novel, I was glad to encounter echoes of it in Lurkers. But the clear lines of Tan’s story don’t pack the same moral wallop as Choi’s more nuanced foray into the lives of teenagers and the teachers who exploit them. Where Choi’s characters are ambiguous, Tan’s are more clearly separated into angels and villains, amoral monsters and innocent kids. While this clarity makes Tan’s story easier to follow, in the sense that the reader always knows who to root for, it also saps her book’s power to unsettle complacencies. Compounding the problem, Tan’s characters also do a lot of schtick, and while it mostly hits the mark, I cringed to read an exchange of letters between Kate and her mother in which they play South Asian stereotypes for laughs, as a way to connect.

As the book closes, the financial crisis of 2008 is looming. Easy credit is bringing house- flippers out in droves, eager to renovate aging properties like the ones in Alta Vista and resell them at unheard-of profits; this housing bubble will soon burst, with painful consequences that include an outrageous bailout for the very banks whose predatory lending schemes brought the bubble into existence in the first place. But the theme that comes through most strongly in Lurkers is less a policy or economic critique than a straightforward plea to keep homes and families together. For the Parks, the loss of a father threatens to entail the loss of a home, a neighborhood, a whole form of life. The threat of such a loss outlines, in the white-hot ink of grief, what a neighborhood means, not to house-flippers or mortgage lenders, but to those who actually live there. Toward the end of the novel, in a recently-unearthed old letter to her husband, Mrs. Park gratefully acknowledges the goodness of their life together in Alta Vista: “Although I began with deep ambivalence, I now love our old house on Santa Claus Lane. I feel happy and contented there. I can see us growing old together under this roof.” Only briefly a reality for Mrs. Park, this poignant closing image lingers as a reminder that, when we long for home, what we miss are the cherished people who make it.

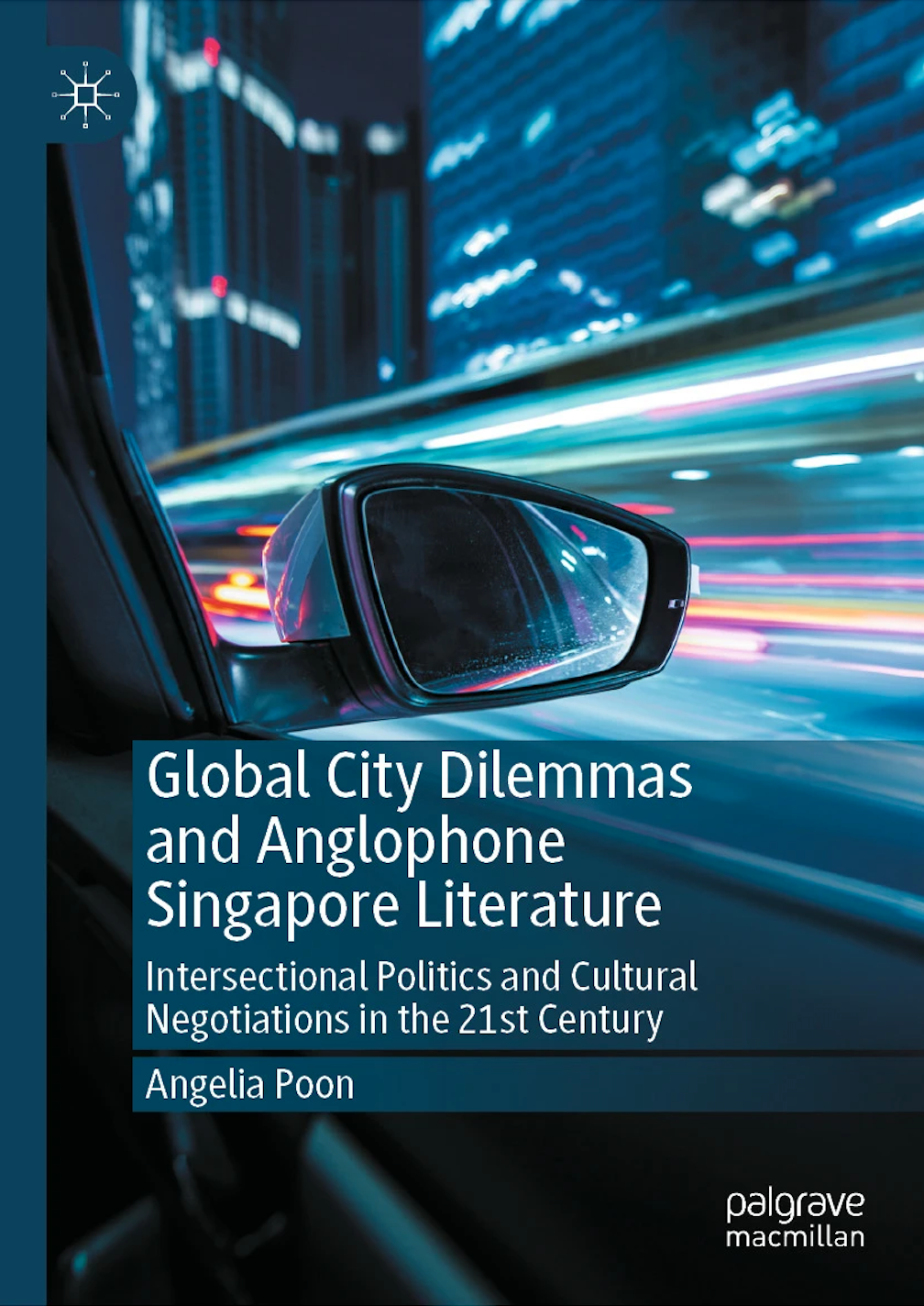

Teresa Eng - Untitled (2014), Elephant, Chromogenic print.

Image description: A close-up shot of a puddle of water by the side of the road with litter, twigs, and leaves surrounding it. A yellowish glow is reflected on the surface of the puddle, implying that it is the golden hour of a late evening.

Diane Josefowicz is editor of reviews at Necessary Fiction. Her debut novel Ready, Set, Oh was published in May by Flexible Press.

*

Teresa Eng (b. Vancouver, Canada) is a photographer based in London, England. Her work explores the inevitability of change through personal histories. Her projects explore the psychological state of trauma (Speaking of scars), the fragmentation of identity in the diaspora communities (China Dream) and the changing nature of neighbourhood and cities (Elephant). Teresa was awarded Martin Parr Foundation Bursary, Burtynsky Grant. She was also finalist for the Aperture Portfolio Prize, Images Vevey Book award and Hyères festival of fashion and photography. Her work has been featured in Aperture, British Journal of Photography, World Press Photo, New Yorker, The Guardian, Financial Times, It’s Nice That and Vogue Italia.

If you’ve enjoyed reading this article, please consider making a donation. Your donation goes towards paying our contributors and a modest stipend to our editors. Singapore Unbound is powered by volunteers, and we depend on individual supporters. To maintain our independence, we do not seek or accept direct funding from any government.

In Taiwan Travelogue, ‘twinned souls… are at once lost, but also found, in translation.’ A review by Eunice Lim.