What It Wants

By Minxi Chua

Charmaine Poh - Room 1 (2016)

Image description: A close-up photo of a girl in a white Singaporean high-school uniform shirt. The top few buttons are undone, revealing a tattoo of a geometric heart on the girl’s chest.

She realizes it’s missing on Wednesday morning.

Standing at the bathroom mirror, glasses askew, toothbrush in her right hand. The left holds her phone, WhatsApp messages from her boss crowding the screen. Need you to stay late tonight, Xinyi. It’s 6:48 AM; the sun will be rising soon. She types a reply: kk can. Her left thumb, unused to the exercise, cramps. Pain shoots down the inside of her forearm, a white-hot needle threading her nerves. Xinyi rolls her wrist, grimacing. The problem needs fixing, she knows. She’ll get around to it, eventually.

Her bathroom mirror is steamed up from the shower, but she doesn’t bother cleaning it. What’s there to look at? She doesn’t wear makeup or jewellery. Just a pair of silver stud earrings she’s had since primary school. Plus the tinted chap-stick in her handbag Cora bought her two or three birthdays ago. It tastes like cherries, dipped in chemicals, but she never goes a day without it.

6:52 AM. Xinyi spits in the sink, clamps the phone under her chin, shimmies into her pants. Her fingers feel weak from the spasm, uncoordinated, like those of a very small child’s. She struggles with the buttons, mumbles mild curses under her breath, looks down to adjust herself—looks down—

That’s when she realizes—it’s gone.

Her phone falls, skidding across the tiles.

She touches her chest, fingers slightly trembling.

Between her breasts, the window of transparent skin, as tall and wide as her open hand, stretched taut like clingfilm over cloudy muscle, the colour and opacity of barley water. Nothing out of the ordinary there. She sweeps both palms across the familiar plane, counting off her visible ribs in Cantonese, a habit from childhood: yat, yee, saam, sei. The ribcage extends from the breastbone, and encases her lungs like a cocoon, protecting the wet, elastic organs, which she watches fill and empty even as her breathing grows uneven. Ribs, sternum, lungs. Next, the heart.

Her heart should be plain to see, tucked in its usual spot on the left side of the chest, thumping to keep her alive. But where is it now? She straightens her glasses, wipes down the mirror and stares into it. Maybe she’s made a mistake. Imagined an absence where none can exist. But her reflection, unchanged in every other way, does not lie. The heart. Where is the heart?

Her heart is gone.

“Shit,” Xinyi mutters.

Then she kneels, dazed and shivering, to pick up her phone.

Checks the time: 7:04 AM. Peter has sent another text: Meeting moved up to 7:15—get here now!

Nestled amidst his demands, a message from Cora: OMG uk work visa just came thru! LONDON HERE I COME! and one from her older brother: r u gonna miss dinner next week 2? mom & dad r pissed :/

“Shit.” Xinyi slicks back her hair. Puts on the bra and blouse hanging on the bathroom door. Takes a few slow, measured breaths. In five minutes, she’s out the door and off to work; only getting home that night after ten, too tired to think, let alone stress out over anatomy. She falls asleep in her office clothes, dreaming of nothing.

+++

Thursday, 6:30 AM. Xinyi wakes to her phone alarm: still tired, a bit stiff, but not dead.

It shouldn’t be possible, to be without a heart. At the office, she does some idle Googling: heart has gone missing; can’t see heart in chest; how to get my heart back? She skims articles on health sites like Psychocardio Today; scours lifestyle blogs; even consults a few conspiratorial videos on YouTube, where skeletal white women in low-cut tops claim that eating only fruit for six months “can combat sudden heartlessness, as well as its related symptoms, like low moods, low energy, and of course, the dreaded weight gain.”

Briefly, she contemplates asking her friends for advice, or even her family. Then she remembers the last time she told her mother she was ill—how her mother insisted she move back into their family’s HDB apartment until she recovered, guilting her every time she showed signs of improvement, since she would soon be “abandoning” the family again. The thought of sitting alone in her childhood bedroom is enough to ensure her silence. Plus, most of her friends she knows from work—personal issues of this nature hardly pass for decent office banter. So she tells no one.

The week passes without incident. Perhaps, Xinyi thinks, everything is fine. I just need to put my head down, work hard, and get on with it. Still, sometimes, an entirely different thought crosses her mind. I wish I could get naked with someone. She wishes she could undo their buttons, strip them down, and inspect what’s ticking away underneath. It’s been years since she’s laid eyes on another human heart up close.

The last one belonged to her then-boyfriend; the one Cora called “Norman”, though that was not his name: “Because he’s such a normie!”. He was an uncomplicated man, friendly and clear-chested. They’d met in university, dated for six years, and broken up in a Marina Bay Sands hotel suite, because she refused to marry him. That entire night, he kept asking her: “What is it you really want, Xinyi?”

Again and again he asked, even as she answered: I want to buy my own HDB. I want a promotion in the next five years. I want my parents to get the hell off my back. Standard, irreproachable responses. Yet they seemed only to upset him further, until, finally, he relented: “I can give you everything you say you want, but it’ll never be enough, will it?”

He had started crying then, naked in bed beside her, and she’d found him unbearable to look at. But she wishes now she had observed him more closely, especially during sex. Now, she can barely recall the details of his face, let alone the most intimate part of his body.

Yet what good would it do to witness the heart of another? What could it change?

Can she stick her fist through someone’s skin, rummage around in their viscera, and extract the core of their being to replace her own? Impossible. Then again, it’s impossible that she still draws breath; that she can take the MRT to work, write reports for investors, eat Shin Ramen at her desk, shit, move, think thoughts, ignore aches, and do all the million other things that constitute being alive, mechanically speaking. Maybe this is the trick to life. You get on with it, even when it stops making sense. You care less about what you want, focus only on what you can get, until you finally stop caring at all, and let the days churn on, steady as a heartbeat.

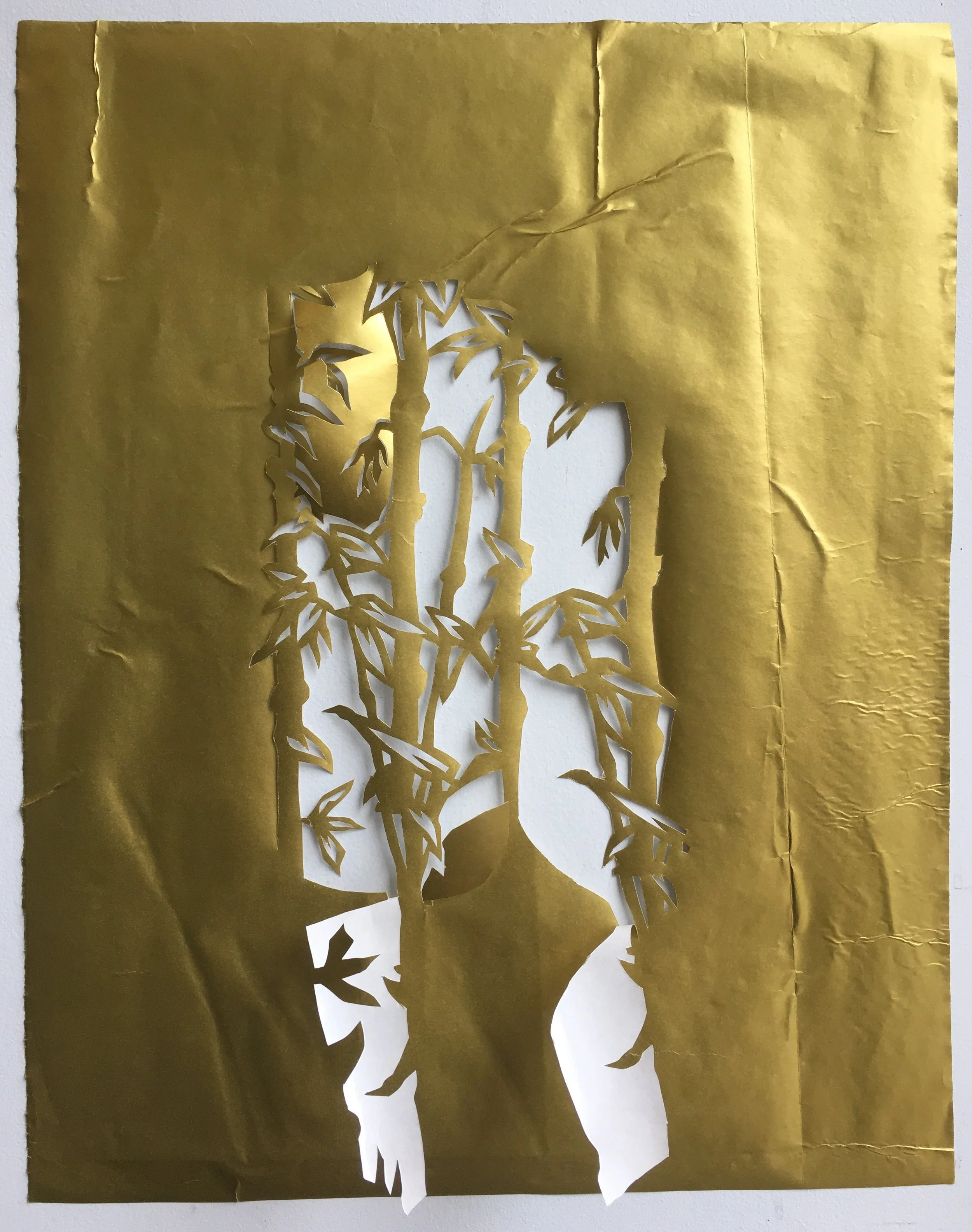

Charmaine Poh - Room 2 (2016)

Image description: A photo of a girl sitting cross-legged on her bed while still in her school uniform. She is holding and also surrounded by small decorative rose bouquets made of paper and ribbons. Near the pink bouquet on the bottom left of the image is a small period stain on the bed.

+++

Then Cora comes over for Sunday dinner.

They don’t see each other as often as they used to. Xinyi is always busy with work; Cora with whatever or whoever she happens to be doing at the moment. But they had been best friends in junior college: the Twisted Sisters, except they were both wild-maned Asians with bad attitudes. During recess, they would cover their arms in sharpie tattoos, competing to see who could don the most daring design: a hairy vulva, an upside-down cross, a swastika.

Once, in Xinyi’s bedroom after school, they took off their pinafores and drew flowers on each other’s chests. Xinyi remembers weaving black vines between the lines of Cora’s ribs: yat, yee, saam, sei; remembers Cora’s soft, fluttering laughter when Xinyi would press down too hard with her pen: “Ah, it tickles!”. They sat side-by-side on Xinyi’s mattress, a hand-me-down from her older brother. The worn, springy foam still smelled pungently of teenage boy, and gave her lower back pain; still, sitting there with Cora, Xinyi had never felt more at ease. But her heart remained hidden under her bralette, as did Cora’s; those glassy panes of secret flesh never fully exposed.

As adults, only Cora has maintained a proclivity for art and inked skin. She’s also a social-justice activist now, and a bisexual. She signs petitions to get drug dealers off death row, goes to Pink Dot rallies with Priya, her “heart partner”, and complains endlessly about everything.

Tonight, her gripe of choice is income inequality:

“But why should fund managers get paid so much? All you do is move people’s money around.”

“You know it’s more than that. Peter says I’ll be up for a leadership role next quarter.”

“Peter works you like a dog, Xinyi. You know, this is why I can’t stand this country. People put up with so much bullshit! Once Pri and I get out of here, we’re never coming back.”

“Not this again, Cora.” Xinyi suspects that she is Cora’s token “normie” friend; less a real human being, and more a topic she can whip out at parties, to use as both scapegoat and punchline: Look at Xinyi, she represents everything that’s wrong with Singapore! She votes PAP in every election, and she only wears panties her mother buys for CNY! Loser alert!

Usually, such a thought would rile Xinyi into righteous anger: If I’m such a loser, then why are you too broke to buy your own dinner? But she can no longer muster the strength to react. For one thing, work’s been tiring; for another, her heart’s been missing for weeks, and she’s convinced it’s not coming back.

Some mornings, she wakes up feeling so drained, wrung so dry of purpose, that she must draw on every drop of willpower within herself to get her blood pumping again. Otherwise, she may not get out of bed at all. She was half an hour late to work last Monday. Peter dressed her down in front of the whole department, but worse than that was the fact it barely bothered her.

“Okay.” Cora stares at her, pierced eyebrow raised. “What’s up with you?”

“Nothing. Do you want dessert? The bingsu place stops delivering after nine.”

“Stop it,” Cora snaps, suddenly stern. “You know I hate it when you switch off like that. I know you’re not telling me something. Come on, spill!”

Briefly, Xinyi thinks she may lie, or distract her with a few insults: What’s wrong? How about your fake-ass relationship? Or does Priya still think you’ll want kids some day, or that you actually like Indian food? Then the fatigue kicks in again, and instead she thinks: Why bother denying it?

“My heart is gone.”

This time, Cora’s laughter is loud and startled. “What?”

“It’s gone. I woke up one morning and took a look at myself and it was just gone. At first, I thought I was going psycho, but lately I feel my pulse slowing down, and sometimes I can’t hear my heartbeat anymore. Don’t worry about it, though. I’ll get it sorted out.”

“Sure.” Cora’s expression is unreadable. As children, they had looked so similar that people often assumed they were related. Xinyi had found this funny, but Cora hated it, loudly and proudly, for reasons she could not, or perhaps would not, articulate. Though by the time she grew out of this strange hostility, the problem was moot. They had grown into two different women: Cora becoming more beautiful by the year, Xinyi more boring. Sometimes, just looking at Cora feels like an act of profound self-loathing. Xinyi must avert her eyes, or else be overcome by unease, a tightening at the pit of her gut, like hunger pangs.

“You don’t believe me.”

“I do!” Even as she says this, Cora shakes her head. “It’s just… are you okay?”

“I told you, I’ll get it sorted out. I’ve just been really busy lately.”

“Right.” For a few minutes, Cora says nothing else. Instead, she pulls out her phone, and starts scrolling. The silence comforts Xinyi. Transports her back to that old bedroom; to those warm, hushed hours hidden inside its walls, where happiness was measured in private pleasures, whispers, glimpses of white bone and blue vein in the afternoon sun. Then her phone chimes, and she is here again: twenty-eight, living alone in an overpriced rental, too exhausted to even feel miserable.

“I just sent you a phone number,” Cora says. “And I want you to promise me something, okay? For my going-away present. No expensive chocolates this time, or designer bags I’ll never use.”

All Xinyi can do is nod. By now, it’s getting late. She’s got to be up at 6:30 AM tomorrow; Cora’s flight to England is in less than a week.

“Great!” Cora’s grin is brilliant, affectionate. “Promise me you’ll make an appointment with the woman whose number I gave you. She’s super nice, a total professional. Priya says she’s politically open-minded too, even though she’s straight, cis and Chinese.”

“Fine,” Xinyi sighs. “She’s a sis? You mean she’s a nun or something?”

“Cis. As in cisgender?” Cora sighs even louder, and shakes her head again, her long, straight hair swaying like a bolt of silk. She looks like Zhang Ziyi in House of Flying Daggers, the killer rebel playing blind; she looks like one of the old ink paintings in the Lee Kong Chian Art Museum, a portrait of some artist’s muse: to be forever adored at arm’s length, yet never again touched, her inner workings never again to be seen, in their grotesque, fleeting beauty. “Forget it. I’ve told you enough times already.”

Xinyi watches her turn to stare out the window, her gaze wistful and distant, as though in search of somewhere to land. Some faraway place where explanations are no longer needed, and understanding another person is as easy as listening to their voice, looking into their eyes, and pressing the see-through skin of your chest against their own, heart-to-heart.

+++

She makes an appointment with Priya’s doctor that Tuesday. She does this indifferently, feeling none of the embarrassment that such a situation should warrant. Perhaps this is the lone upside to heartlessness: an immunity to humiliation. She is even unfazed by the fact that Priya makes more money than her—if the exorbitant cost of the appointment is anything to go by. Or maybe, Xinyi thinks, she’s one of those fancy Indians, whose family makes all the tyres in Eastern Europe or something. Is that better than selling out, Cora? Not all of us can be born so free and lucky.

“So why is it you’re here to see me today, Xinyi?”

“My heart is gone.” She grimaces, as Dr. Tan jots down a note on her iPad. Though the office is spacious, located in a quiet, discreet corner of Holland Village, Xinyi cannot help but feel claustrophobic. Like she is a child again, stuck in her bedroom; like her mother might barge in at any moment and catch her in the act. “I’m only here as a favour to a friend, though. I don’t really believe in therapists.”

Dr. Tan looks up from her notes and smiles, in a manner that Xinyi cannot help but interpret as teasing, perhaps even condescending. “That’s a very common response amongst first-time patients, Xinyi. Unfortunately, there’s still plenty of stigma in our country around Major Acardiognosic Disorder, as well as other psychocardiac disorders. It doesn’t help that the government is constantly telling us to cover up our chests, in the name of ‘public decency’. Still, with the right combination of therapies and medication, MAD can be very treatable nowadays. It’s nothing to be ashamed about.”

“I’m not ashamed,” Xinyi rebuts. “Just confused.”

“You want to know why this is happening to you. I hear that a lot too.”

“So?” Xinyi fidgets in her seat. The armchair she sits in is comfortable enough, its plush cushions freshly dry-cleaned and lavender-scented. Yet she cannot relax into it, cannot find a position or placement that suits her here. “What is it then? Tell me what’s wrong with me.”

To her chagrin, Dr. Tan shifts in her chair as well, mirroring even the way Xinyi crosses her legs. “Well, Xinyi, MAD can be caused by a number of factors. Work stress, for example. Traumatic childhood experiences and romantic relationships are also common. Sometimes, the disorder is preceded by a long-standing issue, like an identity crisis, or maybe a feeling of overwhelming loneliness. Then there are times when it corresponds to one specific event, like losing a loved one, or even moving to a new country. Tell me, Xinyi, do any of these examples sound familiar to you?”

“No.” The conversation does not go much further than this. Dr. Tan asks questions about her family, her love life; Xinyi gives short, factual responses. Once the hour is up, Dr. Tan shakes her hand.

“Well done today, Xinyi. Let’s meet same time next week?”

“Maybe,” Xinyi murmurs. “Sometimes I have to work through lunch.”

That night, she thinks nothing more of the session, or the wry slant of Dr. Tan’s smile.

Instead, she dreams. Dreams of Norman, the ugly, meaty smell of him; the way she would screw her eyes shut when he fucked her, like that could erase his heft atop her, his thin, hairy lips nibbling at her breasts. Dreams of the day she got her ears pierced; the Poh Heng shopgirl pinning her to the chair as she wept, gun to her head; her brother laughing, her mother half-soothing, half-scolding: “Don’t you want to look pretty like all the other girls?” Dreams of the time her mother caught her and Cora with the sharpies, their white blouses strewn across her bedroom floor.

The memory replays in her head as she wakes, unbidden thoughts flashing.

The rattan cane held overhead. The red, swollen welts striping her thighs.

And most of all, the screaming, loud enough for the whole apartment floor to hear:

“Sei cau hai! Dirty-hearted slut!”

Charmaine Poh - Room 3 (2016)

Image description: A close-up photo of a girl with long black hair in a black tank top, lying in bed in a warm, yellow-orange lit room. Her back is facing us, and her mayfly tattoo wing is clearly visible.

+++

She misses work on Friday, and Cora’s farewell party too.

Stays in bed all day, eating pizza in her panties, ignoring Peter’s voice mails.

Saturday afternoon, Cora lets herself into the apartment, suitcases in tow.

“Figure I don’t need my key anymore,” she says, her voice carrying across the living room. Then, more quietly: “And I wanted to see you before I go. Make sure you’re okay.”

“I’m fine,” Xinyi replies. She hadn’t realised that the flight was so soon. Where does the time go? There is a box on her dressing table she’s been staring at for at least a few hours; a jewellery box, wrapped with a ribbon. Nestled inside, a bespoke necklace, a purple flower pendant strung on a silver chain. Such a dumb present, Xinyi thinks. Does Cora even like violets anymore? They used to be her favourite.

“You don’t sound fine. Did you go see Dr. Tan like I asked? About your… problem?”

Problem. Something about the way she says it—the gentle, tentative pity—hurts.

The pain forces Xinyi to her feet, the duvet around her slipping to the floor. She walks forward, through the bedroom door and into the living room. She walks without thought or fear, like it’s the most natural thing in the world, a bodily function as basic as breathing. She walks until she reaches Cora. She is naked from the neck down, apart from a pair of frilly, Hello Kitty underwear. From her pulsing innards to her dark, puckered nipples, she is completely exposed.

Cora’s eyes are wide. Her mouth hangs slightly open.

She’s never looked more stupid; she’s never looked more beautiful.

Then, for the first time in their lives, Xinyi breaks the silence between them:

“Look at me, Cora. I’m fine. You can see that for yourself, can’t you? Come on. Come closer. Why won’t you come take a closer look, Cora? Maybe the bloody thing is still inside me. Maybe you’ll even find it. Please. Look at me? I’m right here in front of you.”

“I can’t,” Cora stammers. She takes a panicked step back, nearly tripping over the coffee table. When she speaks again, she sounds furious: “I can’t do this. What the fuck is wrong with you, Xinyi?”

Again, that agony. Except it is no longer confined to her wrist, or her pride; no, it lacerates her all over. Pierces her bared chest like a lightning bolt, a gunshot, a steel bar. It hurts like it might kill her. Like that rattan cane has flayed her most intimate flesh again. Cora is picking up her bags, hissing as she strides out the door: “You had to drop this on me today? Today of all days? All these years we’ve known each other, and you had to wait until now? When I’m the happiest I’ve ever been with someone else?”

Her final words to Xinyi are: “And you know what the funny thing is? I do see you. I always have. But I can’t wait around for you to see yourself. Not anymore. You need to figure out what you want out of life on your own, whatever the fuck that is. I’ll call when Pri and I are settled in London.”

After she’s gone, Xinyi stands alone in her apartment: for how long, she isn’t sure.

All she sees is the empty room. All she feels are the tears on her face. And all she hears—deep within her chest cavity, amidst the gore and horror of her, the tangled web of capillaries and smothered desires—is a throbbing, loud and sure, proving that she is, despite it all, still alive.

Minxi Chua (she/her) is a writer, editor, and filmmaker from Kuala Lumpur. She is currently based in Bristol, and pursuing an MA in Creative Writing at Brunel University. Her work centers on her lived experiences as a queer Chinese Malaysian woman and explores themes of madness and magic.

*

Charmaine Poh works across image-making and performance, often utilising ethnographic methodologies. Central to her practice are these concerns: the performed labour of the everyday, the gendered body, digital selves, the intersection of offline and online worlds, and the possibility of agency. Her work has been exhibited internationally and been featured in numerous publications. In 2019, she was recognised as one of Forbes Asia 30 under 30 - The Arts. She graduated with an MA in Visual and Media Anthropology from the Freie Universität Berlin and a BA in International Relations (International Security) from Tufts University. She is based between Singapore and Berlin.

If you’ve enjoyed reading this article, please consider making a donation. Your donation goes towards paying our contributors and a modest stipend to our editors. Singapore Unbound is powered by volunteers, and we depend on individual supporters. To maintain our independence, we do not seek or accept direct funding from any government.

‘But later… we didn’t talk about love. We talk about the land and its people.’ – a short story by Kaushik Ranjan Bora, translated from the Assamese by Aruni Kashyap.