A Fair Share

By Shahriar Shaams

Isobel Francisco - Sheets, oil on canvas (2017)

Image description: A painting of a woman with brown skin and black hair, sleeping in a pile of white sheets. Her background is made up of rough brushstrokes in blue, yellow, red, green, and dark-brown hues.

“All our hard-earned money we’ll spend—”

“Not really any of your hard-earned money, is it?”

“Let me finish, Baba,” Bania said, “All this money, mine or not, we’ll use it of course. We love her. Our mother! Spent nine months carrying us inside her own body!”

“What are you getting at?” Bania’s father asked, a little feverish himself. He had little patience today for Bania; in fact, he seemed to rarely be in the mood for Bania these days. He was a man of the factory. He had worked 8AM to 4:45PM, six days a week, the last twenty years of his life.

Bania said, “Fast forward to two months, and we’re bowing to the doctors’ every demand. We’ve practically bankrupt ourselves just to have Ma live, and it’s only then, right about then, she decides to snuff it.”

“Your mother you’re talking about.”

“Rest of our lives in penury! She’d want that, your wife of thirty years?”

The smell of bleach lingered about the plastic three-seaters. The twins were half-asleep beside him; their feet pulled up on the grimy backs of the benches in front of them. Bania wanted to smoke but he didn’t want his father following behind him to shame him. This was the only way the man could be his father. A tradition that went a long way back. When he was a child, Bania’s mother had him bring his father lunch in aluminum tiffin carriers every afternoon. Bania, ten years old, would wait till his father finished eating his mother’s cold rice and watery chicken while accosting him as if he’d cooked it. His sister, Auroni, was only four years old then. It would be a decade before the twins would even be in the picture.

“Where do you think the doctors go to smoke?” he asked.

“They don’t smoke,” his father said, “They’re doctors.”

“You’re saying no doctor ever smokes?”

“It’s bad for the profession.”

“There has to be a few who do it anyway, right? Secretly, discreetly?”

With the help of the co-operative’s leased machinery, used in an often-contentious schedule among the partners, Bania’s father specialized in manufacturing plastic barbs used to keep socks folded in. A glob of wax-like polyethylene that hardened into a hook with a broad shoulder, pumped out in millions.

“The tiny little sock hangers—that’s what our daddy makes!” Bania would say at the dinner table, “We can’t help being proud!”

“Can it, boy,” his father would say, always the nervous wreck, always the embarrassing snort of laughter reacting to a confrontation. Auroni was the lady in the house. Enraged by Bania’s behavior, by her brother’s incessant reminders of their mediocrities, his rallying opposition to any attempt at celebrating them (which, if you ask her, had become suffocating), she would stop any talk with him, hoping her cold shoulder would improve him. Bania barely ever noticed.

And where was their mother? The matriarch who sang them shopping lists for lullabies, whom Bania claimed to have neutralized toward acceptability before the others had come along—even asking to be paid for this heroism—who gave Bania his sense of misplaced oppression, his perennial lust for laying jabs above the clouds shrouding the institution of parenthood?

Presently knocked unconscious at the Delta Medical College’s ICU unit, she had a pipe down her throat, which seemed to wiggle out of her mouth during the intermittent spasms her body performed. Bania had complained of this, but the doctor, all too familiar with the knowledgeable interventions of the next of kin, only patted him on the back. A strategy they had devised to perfection: never humor the family. Only condescend. The only language they would understand.

Their mother, though, was always taking to her bed. It had become a habit with her. At the dinner table, Auroni and their father never acknowledged her. They knew to start their conversations, to begin the ladling of dal to designated plates, the breaking of hardened lumps of rice beneath their fist and releasing them to their individual cuts without much attention or inquiry to her person.

Bania did not understand these implicit arrangements. “Would you get up?” he would go over to say. It infuriated him, added to his persecution that his mother would not act like a mother, that it was his adolescent sister who acted more like a mother. Auroni, even at that early age, would wake everyone in the morning for work or school. She would learn to make tea for breakfast. She would remind Bania of his assignments at college. And their mother, her head buried in the lake of embroidered pillows, would refuse to budge out of her boycott of the dinner table.

“You leave me alone!” their mother would shout back. “I don’t live under you!”

Bania, his face crimsoned in impending failure, waged on: “Enough! Stop this, right now!”

Bania presently got up, straightening his shirt. “I’m going to go see if I can find any of these renegade doctors,” he said, the empty pack of Pall Malls jutting out from his jeans’ front-pocket.

Bania’s father was a man incompatible with the hospital waiting-room. Resting his back only slightly against the concave of the wall, he looked spent. His breathing had become audible. But to stop his son’s departure he was ready to tumble in front of him, grabbing at his arm and pointing him to the square transparency in the middle of the cabin door.

“You can look! She’s right there inside!” he said. “That’s your mother right there!”

Bania stopped. “I can’t look, Baba; I’m unable, simply what with this smell hanging around here. What’s it anyway? Detergent?”

“All you can think of is yourself.”

“I want to clear my head, is all,” Bania said.

“You could’ve been a doctor,” his father said, closing in on him. “Of course, we had hopes for you.”

“Too bad I like to smoke.”

“You like to kill yourself. You have no shame.”

The clock on the corridor said 11:45AM.

“Call me when Auroni arrives,” he said.

Outside the ICU unit, he tied his shoes back on. The corridor, now more spacious and accommodating of the poor and the unhappy, stank of iodine and naphthalene. Pools of betel-leaf stains bore a darker shade of red against the bricked wall. There were blankets, bright in the fullness of one broad dye, lining the corridor—true markers of territory in the wasteland of waiting. Bania tried avoiding their faces, fearing on some level an irrevocable hostility toward him. The unfairness of his mother having a bed, even if she dies in it, when they do not. Their pushed-in jaw, the plastic packs of half-eaten food laid out on the corridor-floor, all pointed out that they’d prefer to lose their bodies in there than be out here still intact, however broken inside.

A winding path beside the floor desk led him to a balcony. The few nurses standing there, having to give him space to pass, glared at him. Bania did not notice much of it, worried as he was that his sister would arrive soon and he would have to return.

“This is a restricted area,” one of the doctors said.

“I’d just like a smoke, you have any?” he asked.

The group in white stopped their conversation to tell him. “There’s a store outside the gates on the left, they sell them there.”

“You can share one with me,” Bania said, coming in. “I’d keep your secret.”

One of the men edged to the front, “Sir, we need you to leave, okay?”

“No,” Bania said. The faces of these men, their self-assuredness, their body movements professing a judgement that somehow nullified him, it scared him for the brief ensuing moment and, almost by instinct, he decked the man.

“—The fuck?” The man, losing his balance, faltered a couple steps back. Bania lunged at him, landing a weak right hook on his shoulder, before the others came to their senses and pushed Bania to the hard concrete. Two of the party held him by the entrance as a third tried stopping the injured man from fighting back.

“Calm down, man!” the men told him. Bania did not struggle against their grip, he hadn’t planned on being an unsuspecting aggressor to this otherwise nice group of people, he didn’t plan on a lot of things these days. They called security.

The man he had hit had a square face, his flat chin sporting a rugged land of beard all the way up his short ears, which looked from afar like sea-horses plugged into the sides. He said, “Is this guy sane?”

Bania mouthed, “Don’t get angry.”

“Don’t talk,” the doctors said. The morning heat hadn’t materialized into a death-march on their skins yet, but the moss, sticking to the crevices of the outer walls, was shining with it nevertheless. Bania did not mind the wait till the authorities arrived.

There was no point in defending himself, and Bania had shot the guards a smile, which he later found had disconcerted them more, amid the small commotion that accompanied his return to the hospital corridor. The nurses around them were scowling, commenting on his appearance, on the lax hospital administration, on the general misery and danger of their profession. He never liked nurses, they ruined pornography for him.

Hauled into the hospital’s security room, past the hundred curious eyes who observed his humiliation, Bania found his sister.

“You’re crying!”

“Bania … ”

“They’ll only slap a fine on me, I’m sure. Nothing to cry about,” he said.

“Bania, Ma’s gone.”

The plan was for Auroni to drive them to their father’s house after she had dropped the children at daycare. Bania ate cereal with hot water and watched TV while waiting for her.

Bania had skipped the funeral. He feared his father shaking him and making a scene, he feared he’d lose it and invite over his mother’s old pals, that it’d be less a funeral and more his father lashing himself (and Bania, for why leave him alone?) for confining his wife to a life of household drudgery. “She had a free spirit, the woman!” he often screamed at Bania during their hospital runs.

He had met her thirty years ago at their hometown’s annual late-autumn fair. “Baba bought Ma from the circus!” Bania would tell his sister when she was still a child. So enamored he was with the girl in a party of other poor females, goaded out of their village homes with promises of fruit and adventure, that he returned for three successive days in a bid to win her affections. He did not know where she came from; she wouldn’t tell him.

“Surely, that should’ve rung some red lights, Baba,” Bania often interjected.

Bania’s grandfather would see it this way too, discouraging his son, still a young man barely out of the District High School, to bring this girl home. But Bania’s father was never one who gave thought to his actions. He belonged to a generation of men who oiled their hair yet still felt modern. “Abba, this is what I’ve decided,” he had said, “How can I go back on myself?” His whole life he had trouble dealing with forces not wanting to go according to his rudimentary plan. He still had trouble dealing with Bania.

Auroni did not come up, texting him of her arrival. He went down to her Toyota and was motioned into the seat beside her.

“Be considerate, please,” she said, edging the car out of the apartment complex parking.

“—This is the first thing you tell me?” Bania said, “No ‘Are you doing well?’ No ‘I wish you had a pleasant morning, brother!’”

“Baba’s going through a tough time, Bania,” Auroni said, “You would’ve noticed if you’d made the effort to attend the funeral, by the way.”

Bania made a face at the window. “Again with the funeral.”

“Baba will never forgive you for this,” she said, “You know it, Bania. I’m not sure I can forgive you either. I understand you have problems with us. You don’t like any of us—”

“I never said I didn’t like you,” Bania said, closing his eyes and leaning back.

“You don’t act like you do! You’re always trying to hurt Baba, trying to get back at him.”

“—the man can’t stand me!” Bania said.

“Ever since they had the twins you’ve been going at them as if it was some crime.”

“Having children again at that age? Oh c’mon, this was to spite us.”

The traffic gifted Auroni the chance to look over her brother. “You think Ma got herself pregnant just to spite us?” she asked.

“I’m telling you: the woman was capable of far worse!”

“Our dead mother you’re talking about, Bania,” she said, her hand firmly on the steering wheel, swerving a little too stridently to cut an angle.

“Don’t go off on Baba today,” she added. “Please, he’s being crazy as it is. He wants to give all of us our “stuff” today. He’s saying it’s time we got our inheritance from Ma.”

Bania said, “What inheritance? She didn’t have anything.”

“…I know that. I have no idea what he’s got planned for us.”

Bania sat up, facing his sister. “He wants to get rid of the twins. He’ll be giving them away to us!” he said.

“…”

“Let me out!” he started to shout now. “I’m not falling for this!”

Auroni jerked him to his seat with the other hand, “Bania, stop it. I’m losing sight of the street ahead.”

“They’re going to kill me the way they killed Ma!”

“Enough, Bania. They are children. Your own blood. How can you talk like this?”

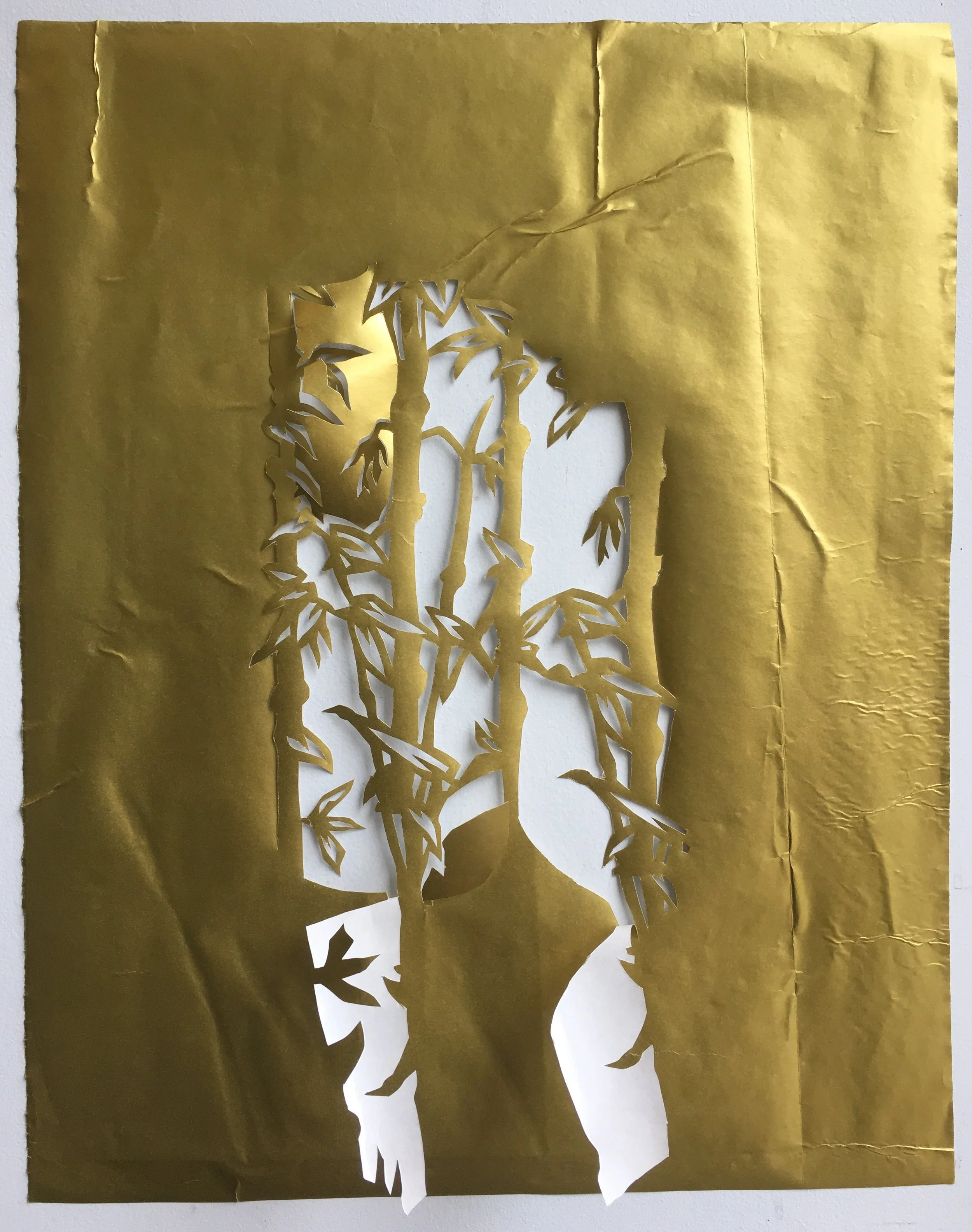

Isobel Francisco - Settlement, oil on canvas (2018)

Image description: A painting of a pile of bones with a pelvis and ribcage bone at the top being the most prominent and recognisable bones. The subtle image of a woman’s decaying face hides within the pile of bones. The color palette consists of browns, yellows, blues, and hints of pink.

Bania sat in silence, only making noise fiddling with the air-conditioner dials. The Toyota edged into their old road. Bania remembered walking by this footpath only a week ago with his father at night, assuring him or being assured (they never knew who was doing the assuring) during their return from the hospital. His father would talk about the many ways Bania had let him down and Bania would counter him with the many ways his father had failed to give him his due.

“I’d have to stop the business any day now,” he’d say. “I’m too old now.”

Bania would reply, “Not enough to stop procreating.”

“Amzad bhai’s son Heshie comes by the office every day. His father spends his mornings at home reading his newspaper. The man is illiterate, did I ever tell you that? He can’t read but he’s got time to read. He’s got himself a pet cat, too, the old man! Not a care anymore for work orders or machine failures. And look at me, still having to go out to war in this decrepit state. Answer me, Bania, are you this ashamed of your father that you wouldn’t want to take over the family business?”

“Your business isn’t exactly the commercial empire you’re making it out to be, Baba,” he’d say.

His father would shout, “You have no respect for your mother!”

Bania would stop walking. “You should get Slow-mo to take over after you,” he’d say, “I’m sure Auroni would love the idea.”

His father, unable to ever gauge whether Bania was being serious or not, would innocently reply, “They already do so much for us. They babysit the twins; they bring the food to the hospital. Don’t talk about him like this. What do you do? Where is your share of the contribution?”

*

Auroni parked the Toyota out on the road, behind her husband Shomo’s Toyota. Everyone in this city owned a Toyota: crumbling Corollas with scotch-taped headlights and driving seats topped with reeking, grimy towels.

Shomo was keeping watch over the twins out in the living room.

“Slow-mo!” Bania called out.

Auroni said, “Bania, behave, okay?”

Shomo resembled his father-in-law more than Bania, perhaps lacking only the display of contempt his father-in-law had grown over the years to express at Bania. He was happy to be in the family, and though he had a successful law practice, he would’ve gladly agreed to help out with the factory if asked. Even Bania’s jibes, he didn’t mind. He wanted to befriend him, even though his wife would laugh at the prospect, claiming that her brother would be only too happy to find another way to annoy her.

“Where’s Baba?” she asked him.

“He was watching TV for a while,” Shomo said, “but then he got up and started rummaging through his room. I didn’t want to disturb him, so I’ve been hanging out with the twins.”

They found their father at the kitchen table, seated with his hands bunched up and touching his chin. “Please, sit down,” he said.

“—What’s got into him?”

His eyes were red; he had been rubbing them. There were newspapers on the floor, stained in soot and what looked like a smattering of dirt.

He got up to get a cardboard box, which he stationed in front us. He said, “With your mother gone, I wanted to get this done with. Bring the twins in here, too, Shomo. They may be too young to understand, but they shouldn’t miss this.”

“Baba, are you okay?” Auroni asked. “Are you sure we have to do this now? There’s still time.”

To her husband, she shot an anxious look.

Bania climbed up the table to sit on the other end of the box. “This better not be old circus equipment, Baba,” he said. “I didn’t come all the way here for that.”

His father ignored him, proceeding to open the soggy upper flap and bring out four boxes of transparent Tupperware.

“Baba—what is that?” Auroni asked, noticing the contents inside and wishing dearly it wasn’t what it looked like.

His father, crying now, said, “It’s your mother’s ashes!”

The mixture of snot and tears crowded in hideous pools over his unshaved face.

“You put Ma in Tupperware?” Auroni asked.

Bania stared at his father, who tried to hand him his share. “Take it! This is yours. I labelled the containers so I wouldn’t mess it up.”

“Shomo, take the twins out please, will you?” Auroni said.

“No! They can’t leave without taking their share first. Let them stay, Auroni.”

Bania, too stunned to react right away, opened up the Tupperware and looked intently at the contents, wondering if it really was his mother’s ashes, or some psychotic joke his father deemed too funny to pass up. Then he noticed how much he received.

“—You gave me less!” he said. Years later, he’d be surprised that this was what he had to wrangle about, not his father’s weakening mental faculties, not his sister’s naivety in not taking action any sooner, but this. “Why am I getting so less? I’m the oldest here. And look how much you gave the twins! What’re they going to do with so much? Make sand-castles out of her ashes?”

“I gave you enough, boy,” his father said.

“This was a big woman we’re talking about!” Bania said. “It’s not like we cremated a skinny, underweight lady! There has to be more of her. You’re skimming off my share!”

“Bania, shut up,” Auroni said.

“The boy wants everything for himself! Please, Auro, dear,” their father cried. “Please, when I die, don’t let him anywhere near me! Bury me when I pass away, bury me so he can’t come steal my urn!”

“You give me my fair share and I wouldn’t have to steal anything!”

In anger, the father tried taking the container away from his son. Bania, in turn, clutched it tighter. “Look!” he motioned toward his sister, “The old man has to take everything from me!” The twins cried out, unable to process the commotion. A sharp, tangy odor hung over the kitchen; it did not mix well with the jasmine water Bania’s father had sprayed beforehand over the Tupperware. An inevitable tussle—the son demanding a piece of his predecessor and the father denying him. “Stop it, please!” Auroni screamed. Bania, at last, let go, only for the container to slip off and split open. Their mother’s ashes rained on all her children, inviting a stillness that equaled the intensity of discord to come.

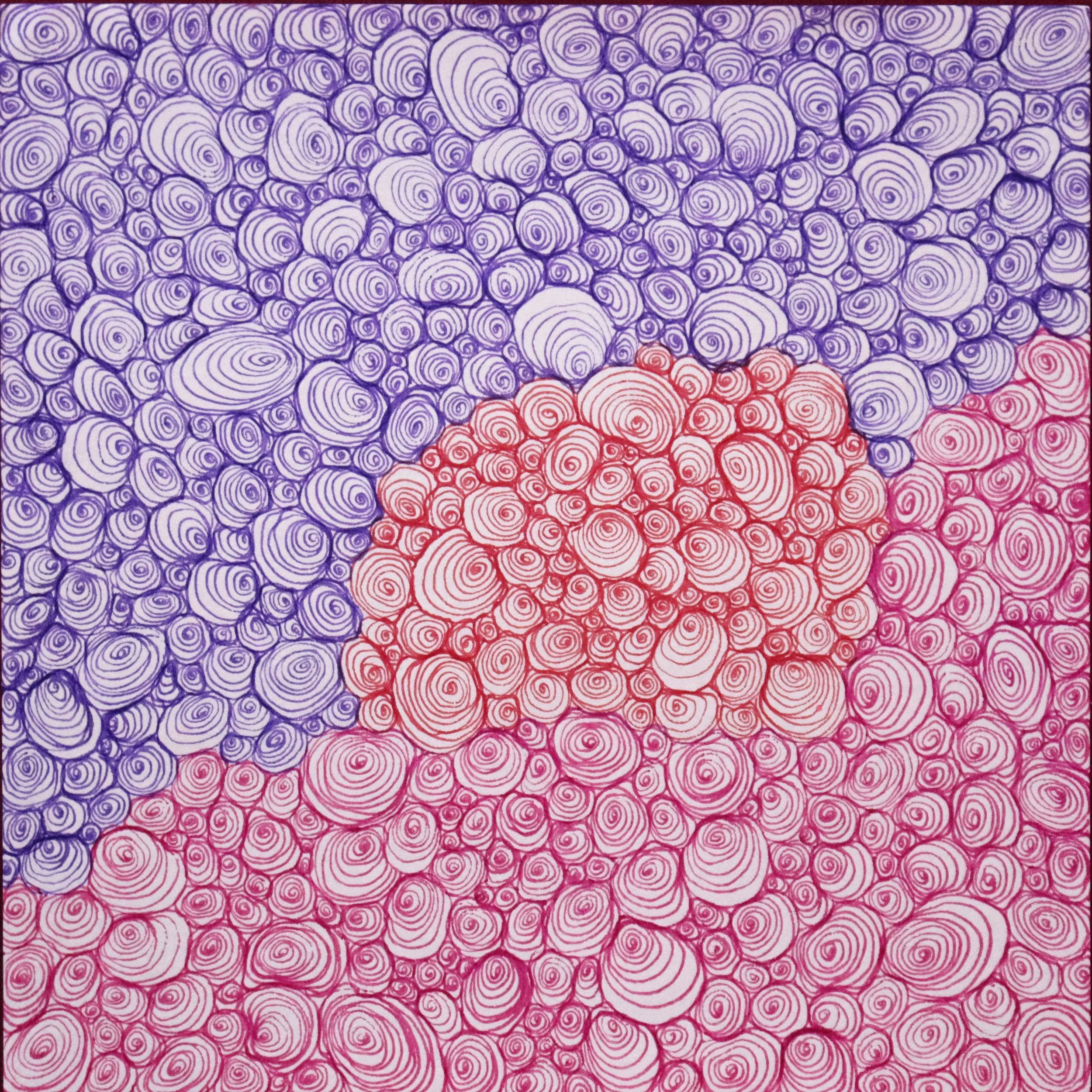

Isobel Francisco - Mother, oil on canvas (2020)

Image description: A large crumpled sheet of canvas hanging on a white wall. The canvas has a painted image of an old woman in blue, purple, and brown tones with hints of white and yellow.

Shahriar Shaams lives in Dhaka, where he attends business school and occasionally boxes in the local amateur scene. His essays, fiction, and translations have previously appeared in Six Seasons Review, Jamini, Singapore Unbound’s SP Blog, Dhaka Tribune, The Daily Star, and Commonwealth Writers' Adda.

*

Isobel Francisco is a Filipino visual artist. Since her first group show in December 2011, she has exhibited in Hong Kong, Germany, China, and various corners of Metro Manila. Her works currently involve figurative tensions and narratives of anguish, loss, and the constant examination of what constitutes humanity.

If you’ve enjoyed reading this article, please consider making a donation. Your donation goes towards paying our contributors and a modest stipend to our editors. Singapore Unbound is powered by volunteers, and we depend on individual supporters. To maintain our independence, we do not seek or accept direct funding from any government.

‘But later… we didn’t talk about love. We talk about the land and its people.’ – a short story by Kaushik Ranjan Bora, translated from the Assamese by Aruni Kashyap.