#YISHREADS May 2022

By Ng Yi-Sheng / @yishkabob

Somehow this month I’ve ended up digging into a bunch of classic Asian literature of the early to mid-20th century. What can I say? I’m an antiquarian at heart (us gays love vintage sh*t), and I’m curious to know where our current tradition sprang from. What’s less expected is how a fair number of authors from the era were women—our literary pioneers weren’t as monolithically male as our canons suggest.

Mind you, I’m still leafing through recent stuff, including Vida Cruz and Yangsze Choo, both of whom are making waves in Southeast Asian speculative fiction. I’d also very much wanted to feature the first collection [1] of an excellent young Singaporean poet, but alas, Singapore Unbound’s placed a moratorium [2] on all dealings with her publisher. Ah well: we each pick our own battles in the name of social change.

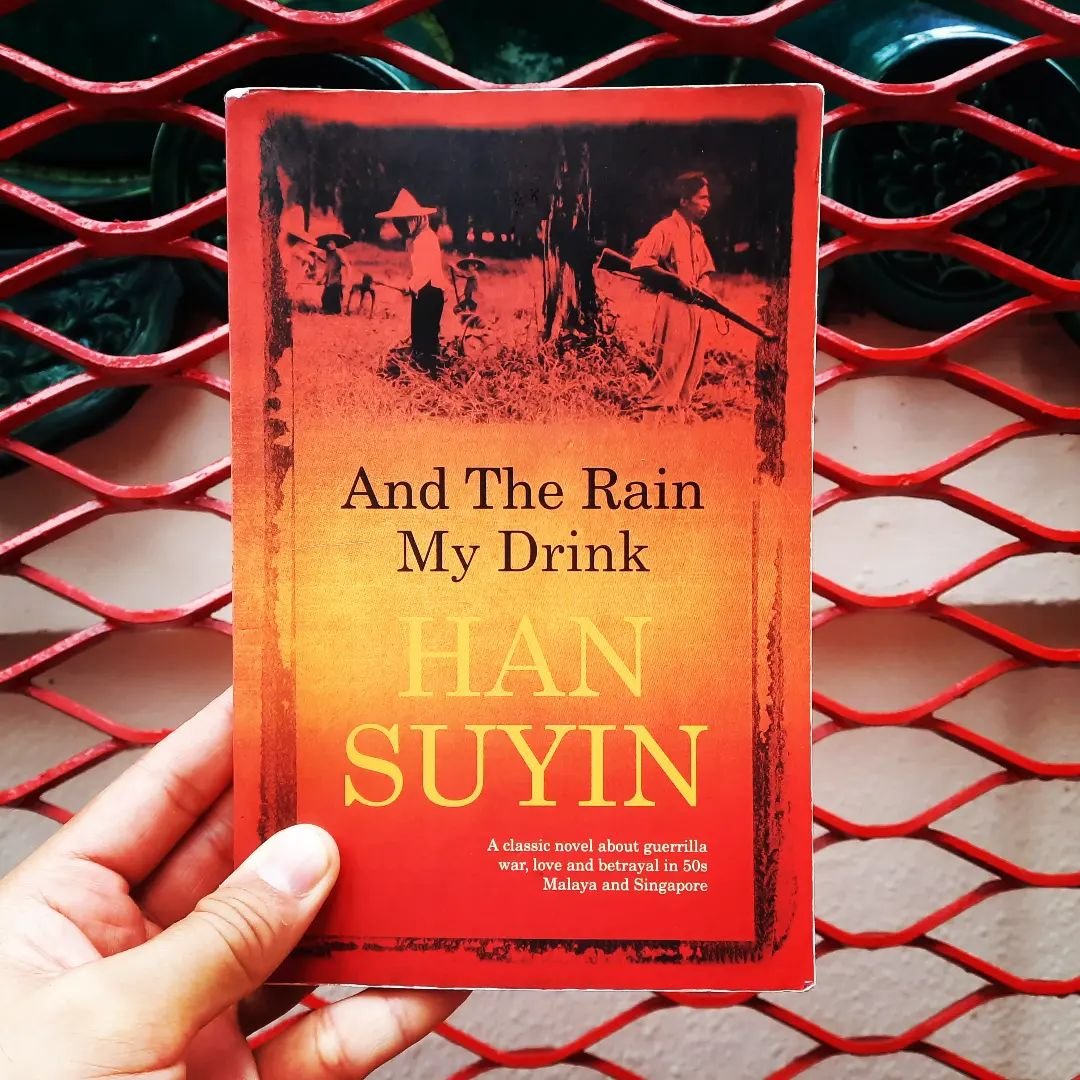

And the Rain My Drink, by Han Suyin

Monsoon Books, 2010

I'd heard a bunch about this author—a half-Chinese, half-Belgian doctor whose English novels were adapted into Hollywood films and who taught at Singapore’s long-lost, Chinese-medium university, Nantah—as well as this 1956 novel of hers, which depicted the Communist Emergency with such sympathy that her British military officer husband Leon Comber ended up leaving the Special Branch and divorcing her.

What I didn't expect was that it would be so gorgeous. She's describing everything she sees in Malaya and Singapore not only with vivid detail but a magnificently broad and lyrical vocabulary, from casual street scenes of convent school girls, mosque attendees and hawkers to the glitz of a Peranakan banquet where magnates and colonists broker deals about the future of the land that is not yet free. And next to all that lush beauty, the nightmare of colonial violence, as Chinese are summarily detained, moved from their villages into concentration camps, their houses burned and their pigs slaughtered, for fear that they'll help the same Communist guerrillas who liberated them from the Japanese—not just the trauma of separation and the squalor of the New Village, but also the sheer horribleness of not knowing what your crime is, how long till you'll be exonerated if ever, the Kafkaesque gap between captivity and trial and freedom.

Also surprising is her thoroughly female perspective. The POV character's clearly semi-autobiographical: a doctor struggling in a women's wing of an underfunded hospital, where numerous detainees are held, whimpering from nightmares, suckling their children till they're three or four years old, culminating in a Seventh Month explosion of occult hysteria. Yet it's not just women as victims: we see women revolutionaries, businesswomen, weightlifters, interior designers, some morally bankrupt (there's special scorn for the mems, who're eager to use the detainees as lowly paid service staff), all of them operating with their own agency—even a casual mention of amahs forming lesbian relationships! (There’s also a reference to Punjabi security guards doing something unspeakable, which I’d at first thought was a magical ritual, but which my commenters read as gay sex.)

And then there’s the cleverness of how she's depicting the violence of colonialism, by first introducing us to some extremely well-meaning Brits, then revealing how it's impossible for them not to end up horribly harming people's lives under this system. Mind you, she shows that the Communists are wont to inhumanity themselves, what with their summary executions and murders for the greater good, and self-criticisms—there's a constant fear of internal treachery that I thought only surfaced during the Cultural Revolution.

Then there's the sheer literariness of this work—it's not just an exposé of bad politics; she's literally shifting in and out of people's minds, Woolf-like, dividing a single day into hours ruled by the influences of the Zodiac and blossoming into a single moment of almost-epiphany as the Peranakan woman known as either Intellectual Orchid or The Abacus sits in Kallang Airport, about to rescue her daughter from joining the Communists in China, almost falling in love with the idealistic but self-destructive British police officer Luke Davis.

I'm afraid I'm not describing the book well enough. It just contains volumes, and it's crazy that we haven't fully absorbed it into our national canon yet. (“We” being my own generation—turns out my dad read all her books when he was growing up in the sixties!)

Cat Town, by Sakutaro Hagiwara

Translated by Hiroaki Sato

New York Review Books Poets, 2014

This poet (1886-1942) was one of the great Japanese modernists, known for breaking out of tanka into free verse, though our translator explains that he continued to combine classical and vernacular language in his very weird work—seems he had this morbidly bratty personality (both his wives left him) that manifested in Baudelaire-ish, Rimbaud-esque delusional views of the world around him, encapsulating beauty and desperation and a whole lot of newly imported language (katakana, I suppose?) which the translator represents in italics.

This collection is mostly made up of his breakout volume Howling at the Moon (1917) and Blue Cat (1923), with additional works including the titular novel/roman/prose poem Cat Town (1935, originally published w illustrations!). But the prose poem that catches my eye the most is “The Octopus That Does Not Die”, in which an octopus in an abandoned aquarium literally eats itself into oblivion. Was this the inspiration for the story of the similarly auto-cannibalistic monster Can in Singaporean playwright Kuo Pao Kun's 1998 play about the trauma of the Japanese Occupation of Singapore, The Spirits Play?

Thai Short Stories, by Thai P.E.N. Edited by Witt Siwasariyanon

Thailand Centre, International P.E.N, 1971

This little antique is a 1971 reprint of a 1964 collection, with an intro that suggests its five authors are among the pioneers of the Thai short story form in the early 20th century.There's quite a bit of overlap here with moralistic/religious fables, e.g. a man in Vetal's “Rain in the Fifth Lunar Month” deciding to take another man's place in an execution just cos a monk got rained on; also Riem-Eng's “Nang Phanthurat's Gold Mine” revealing the folly of the pursuit of wealth when a dude who's spent his entire life in pursuit of a fabled source of gold finally discovers it, then realises the peace of the sacred hill means much more than any $$$ he could get from it. Some exploration of the danger of religious inflexibility in “Rising Flood”, though, also by Riem-Eng—a girl dies swimming across a stormy river because a monk refuses to succumb to her love.Some cosmopolitan surprises await, mind you. Dhep Maha-Paoraya's “Champoon” is set in Phuket, featuring a man-about-town who falls deep in love for a Chinese towkay's daughter (the dad's so fiercely protective he only allows her to study at a convent in Penang) but ends up with a sexy Filipina, just in time for the distraught Chinese girl to catch him—there's some Gothically nightmarish flourishes here, though, and the girl ends up naked in chains and eaten by a crocodile! Also Archin Panjaban's “Heat and Heart”, which is set in a tin dredging outfit in the south of Thailand, focussing on a Malay Muslim character, Ben. The Buddhists among him first mock his suffering during Ramadan, when he can't drink water to slake his thirst while pitching wood into the fire, then rally around to try to alleviate his pain.Alas, I can't get further info on any of these authors except K. Surangkhanang (1912-99), whose story “The Grandmother” is the most sappy social realist tale of kids neglecting their long-suffering elders ever. She does seem like a writer to check out, mind you—Wikipedia says her 1937 novel The Prostitute was both scandalous and influential! 😮

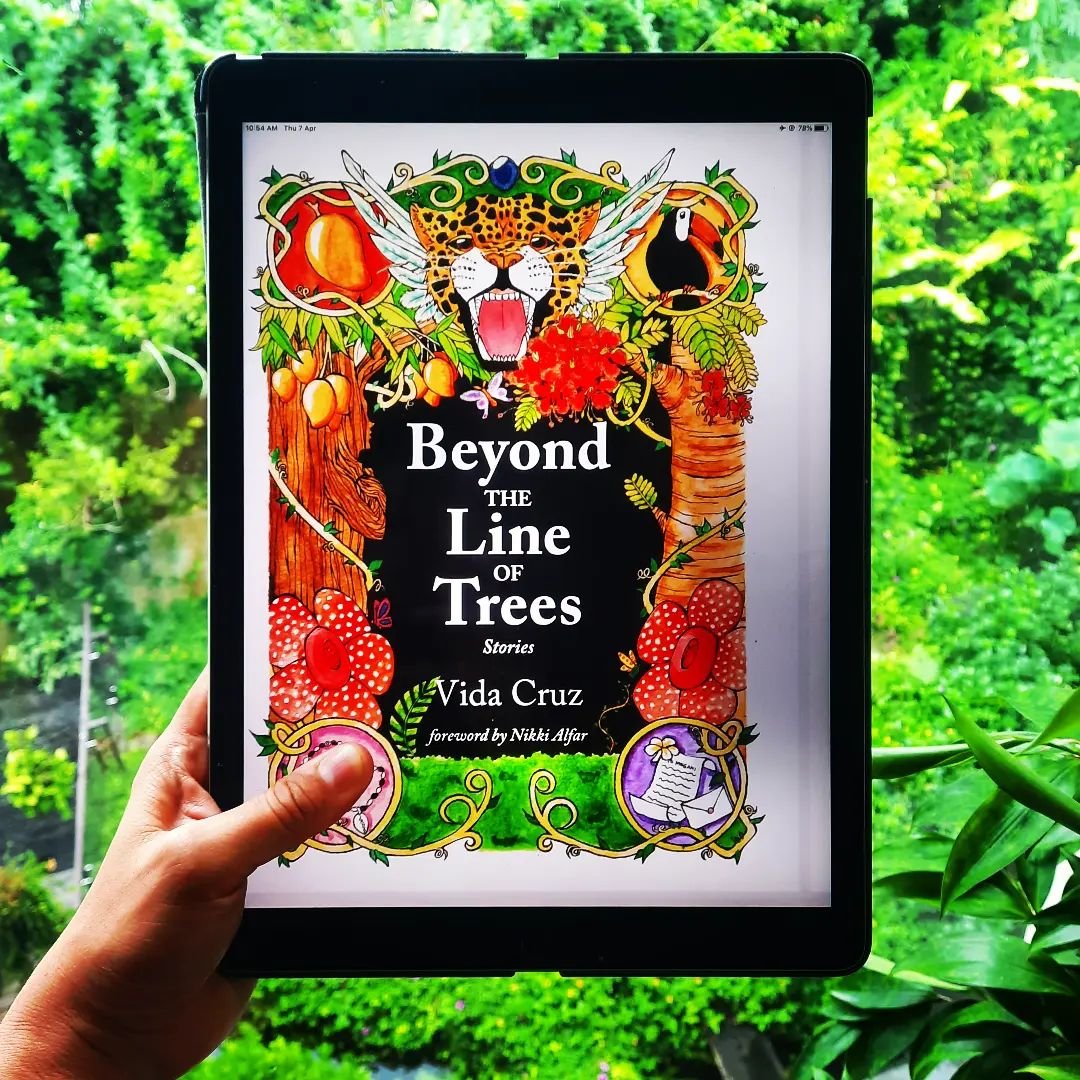

Beyond the Line of Trees, by Vida Cruz

Self-published, 2019

I first encountered Cruz during her talk, “Ways to Decolonize Your Fiction Writing [3]”, at last year's Flights of Foundry online SFF festival. Since then I've cited her remarkable essay “We Are the Mountain: A Look at the Inactive Protagonist” [4], chatted with and consulted her on Facebook. This, however, is the first time I’ve hunkered down to read her work. And I'm glad I have: what she’s given us is a quartet of fantastical short stories, beautifully written and illustrated, all working with decolonial strategies, but accessible even to kids.

The first piece, “How the Jungle Got Its Spirit Guardian”, is set in precolonial Mexico, but not in one of the great empires; it's a tale of generational heartbreak and kids learning how they can subvert expectations of their gender, all set in a tropical tribe. “Song of the Mango” shifts to the precolonial Philippines, and once again dwells on the power of ordinary non-nobles to escape the cruel domination of kings; the same people we'd point to today as evidence of early “civilisation”. “To Megan, with Half My Heart” is urban fantasy, centred on a schoolgirl courted by a kapre (though the question of whether she loves him is fascinatingly mixed). The final tale, “Odd and Ugly”, is another kapre story, but this time a riff on Beauty and the Beast set in the Spanish colonial era—it also plays w a fascinating theory regarding the possible origins of this mythical creature: could the kapre (tree giant) be linked to the Cafre (person of African descent)?

The book's available at vidacruzwrites.gumroad.com (physical copies too in Malaysia, where it was printed), and her essay and talk may be accessed via the links provided. Check ‘em out!

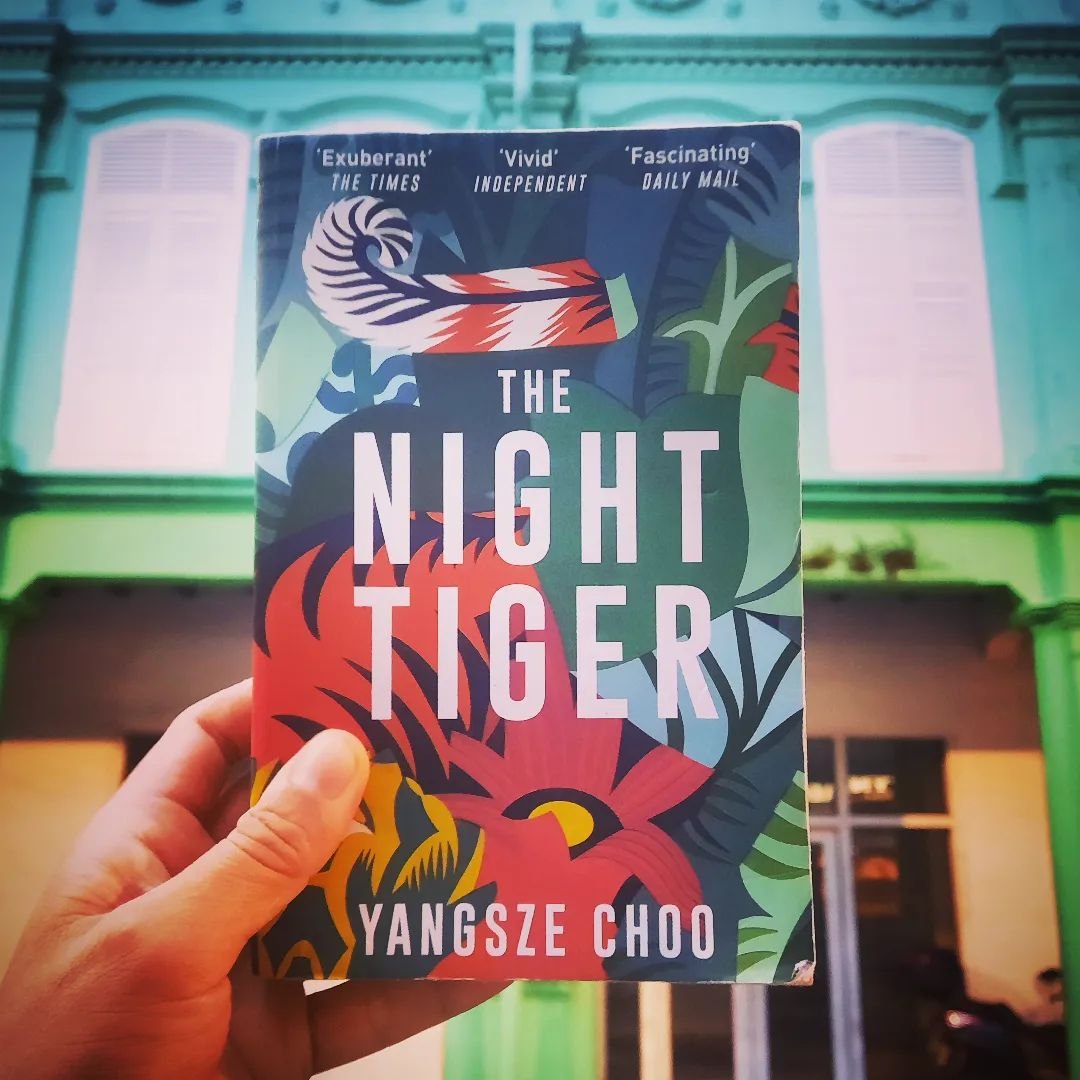

The Night Tiger, by Yangsze Choo

Quercus, 2019

I shared a horror panel with this author at Singapore Writers Festival 2021, “Beware the Smell of Frangipani At Night”, and both my father and I enjoyed the hell out of her first novel The Ghost Bride. This follow-up’s a New York Times bestseller and a Reese Witherspoon Book Club pick! But oof, I've got thoughts about it.

First, let's give credit where it's due: this book is super-ambitious. Much more so than The Ghost Bride, which was narrated entirely from a single POV, and anchored firmly in legends of the Chinese afterlife (to the extent that its 19th century Melaka setting feels kinda incidental). This work, in contrast, has three POVs, meeting and mingling in 1930s Ipoh and Batu Gajah: the 11 year-old houseboy Ren, the dancehall girl Ji Lin and the colonial doctor William Acton. Plus, it's dipping its toes into a whole mess of genres—historical novel, romance, horror/SFF, crime, and even a touch of hospital drama.

The result is a story that feels way too convoluted to me; so much so that (SPOILERS BELOW!!!) its title premise, that of the harimau jadian, the weretiger, never pays off: after endless hints and hauntings, the creature never makes its climactic appearance. That plot thread's just dropped by the end. Plus, despite Ji Lin's scandalous profession, she is so priggishly insistent on maintaining her virginity that she refuses to sleep with the man she loves before marriage, despite the whole fanfic trope of there being ONLY ONE BED. Plus, there's this also whole business of her beloved being her stepbrother! And pretty much all the women who do display sexual agency in some way end up getting punished for it—especially the two Indian coolie women that Dr Acton is hot for, who die horribly.

Which brings us to the topic of race. Sure, I get that Chinese Malaysians don't experience privilege the same way Chinese Singaporeans do; that Malay Malaysians might not even want them to write about them; that it's a tough sell with Western readers who have no pre-existing notions of Malay culture. But it's downright crazy that in a story that fixates on the harimau jadian, where its associated beliefs and the Malay language is invoked to explain it, we have virtually no Malay characters. The principal weretiger is in fact a white man, the recently deceased Dr MacFarlane (only seen in flashbacks). It's appropriative, the same way Gilbert Chan's horror film 23:59 and Sharlene Teo's novel Ponti refused to centre Malay characters despite using Malay hantu as their selling points.

Makes me appreciate Zen Cho's The True Queen, which did feature a Malay protagonist in a Western-published SFF novel. You see, it's possible! Ren could totally have been a Malay character! (And yes, I know there's the whole question of why Malay writers aren't getting the same platforms, but I do think we Chinese writers could be doing a better job with the opportunities we have.)

Ng Yi-Sheng (he/him) is a Singaporean writer, researcher and LGBT+ activist. His books include the short story collection Lion City and the poetry collection last boy (both winners of the Singapore Literature Prize), the non-fiction work SQ21: Singapore Queers in the 21st Century, the spoken word collection Loud Poems for a Very Obliging Audience, and the performance lecture compilation Black Waters, Pink Sands. He recently edited A Mosque in the Jungle: Classic Ghost Stories by Othman Wok and EXHALE: an Anthology of Queer Singapore Voices. Check out his website at ngyisheng.com.

If you’ve enjoyed reading this article, please consider making a donation. Your donation goes towards paying our contributors and a modest stipend to our editors. Singapore Unbound is powered by volunteers, and we depend on individual supporters. To maintain our independence, we do not seek or accept direct funding from any government.

In Taiwan Travelogue, ‘twinned souls… are at once lost, but also found, in translation.’ A review by Eunice Lim.