Autofiction, History, and Beyond

Shawna Yang Ryan Talks to Fiona Sze-Lorrain

This conversation began shortly before Scribner’s publication of Fiona Sze-Lorrain’s new novel, Dear Chrysanthemums, this May. Here, Taiwanese-American novelist Shawna Yang Ryan discusses with Sze-Lorrain about artistic influences, autofiction, oral history, historical fiction, as well as motherhood and writing practices.

Shawna Yang Ryan is the author of Water Ghosts (Penguin, 2010) and Green Island (Knopf, 2016), winner of the American Book Award. From 2017 to 2023, she was the Director of the Creative Writing Program at the University of Hawai‘i at Mãnoa. Other than her novel Dear Chrysanthemums (Scribner, 2023), Fiona Sze-Lorrain’s work includes five poetry collections, including Rain in Plural (Princeton, 2020) and The Ruined Elegance (Princeton, 2016), and fifteen books of translation from Chinese and French. She is also a zheng harpist.

Shawna Yang Ryan

Photo credit Anna Wu

Fiona Sze-Lorrain

Photo Credit Sabine Dundure

Shawna Yang Ryan: I’m wondering what literary genealogy you situate yourself in. Also, what other kinds of art/artists your work might converse with?

Fiona Sze-Lorrain: Your first question is already the toughest!

I don’t know about genealogy . . . I’m constantly experimenting as a writer and reader. I have a voracious appetite for books and well—life. I take risks. I don’t believe in habits. That applies to my reading life. But I’m austere with words on the page and like to see myself working in the vein of writers who exercise precision and economy. Joan Didion comes to my mind. I don’t wish to write so to hide or arrange “something” neatly—I want to write exactly what I think and feel, how I breathe. Even in emails, I try to practice that sort of linguistic yoga or qigong.

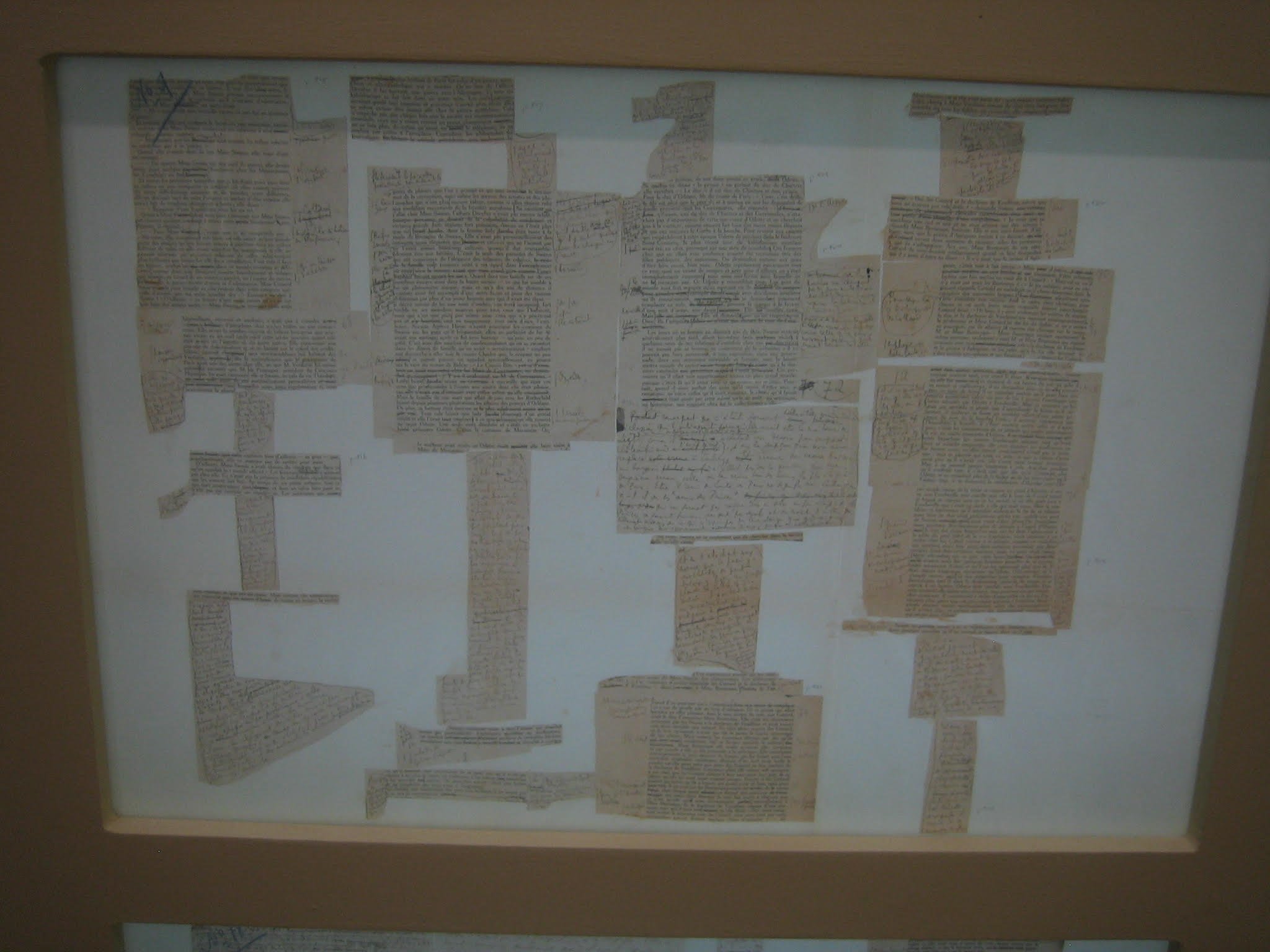

I discovered Amy Tan at ten. I was thirteen when I first read a poem by Victor Hugo. Every summer since 2003, I try to keep a month for Proust. That’s my ritual. Earlier this year, I visited a Proust exhibition at the Bibliothèque nationale de France in Paris. It was humbling just to view Proust’s archives—how he labored over every word, with or without madeleines. He worked for timelessness.

Exhibition: Marcel Proust (La fabrique de l’œuvre), BnF, Paris

photo by Sze-Lorrain, January 2023

Contemporary art—abstract paintings in particular—interest me. For a while, I was obsessed with daguerreotypes. I also studied typography. It’s hard to discuss art: I strive to look at art as it is and not invent discursive contents. I want to see what I don’t know. I don’t find the state of “knowing” or “having knowledge” appealing. Now that most of us might live more in the digital than in the real, much of our connection with our own “third” eye can be compromised. But I’m hopeful about the future, our return to the sacred, the unknown yet the concrete. Beauty is more of a physical experience for me. It’s close to silence. I make paper and appreciate Japanese textile art.

Yang Ryan: Such a rich collection of influences! I see that in your work: the lushness and the subtlety. Saving a month for Proust—that’s a lovely concept.

You mention Amy Tan—I wonder if you were like me—for a long time, she was the only Asian American writer I was exposed to as a young woman in the 90s. So she is always there, lingering. Then I had the wonderful opportunity as an undergrad to work with the scholar Anne Cheng, who introduced me to Theresa Hak Kyung Cha’s Dictee, a book beloved by so many feminist Asian American writers. I love books that must teach the reader how to read them.

I think about art a lot too when I write, and how to translate the texture of certain images into language—how to use language as a medium, what its strengths and constraints are. Recently I started working on autofiction—I’m teaching a graduate seminar on it right now—and so I’ve been drawn into second-wave feminist art—collage, photography in which the subject is not the subject. I also think of Vija Celmin’s exacting photorealist drawings—it’s a bit like autofiction—to make a fiction look like truth.

Sze-Lorrain: This is a refreshing take. What kind of truth? Aesthetic or emotional, or political? It sounds like making a lie more credible, some mise en scène. I don’t mean it in a negative way. I assume the intentions are honorable. But I’m curious about the conflicting forces. What difficulties have you experienced with autofiction?

That said, working with autofiction sounds liberating in that it might discard clichéd questions such as “How autobiographical is your work?”

Yang Ryan: I’ve always been intrigued by the idea of writing texts that appear factual—like a textbook—but are fictional. I imagined once doing a book of book reviews about books that didn’t exist. Now that I’m mentioning it—maybe I still will!

Autofiction works in the other direction. The scholar Yanbing Er offers a definition of autofiction that captures what I like about it: “self-reflexively traversing, and oftentimes rejecting, the already unstable boundaries between fiction, autobiography, and theory.”

I find autofiction really freeing—it feels like I’m freely spinning into a beautiful web all the texts that compose me—I feel more free to engage with pop culture, social media, current politics. I like the freedom of being able to fill in gaps with fiction. Er notes “unstable boundaries”—with autofiction, the story play can extend out into the paratext, which is fun.

Sze-Lorrain: I wish I’d found your autonomy with autofiction. I’m less suspicious of the label “autofiction” than of the emphasis on me, I, my. I’m not too curious about ego- or self-based narratives. The collective existence is more engaging. This could be why I’m keen to let a building, street, or place take center stage in my stories in Dear Chrysanthemums—the Wukang Mansion in Shanghai, rue Séguier in Paris, etc.

I find the nonhuman, the animism more helpful to my work and thinking—and to taming my own ego. Way to go for non-attachment, alas. Note that I’ve already used I and my three, four times!

Back to the collective. You engaged extensively with oral history in your research when working on Water Ghosts and Green Island. Do you find the multiplicity of voices daunting? And how do your stories converse with history to stay relevant with the actuality?

Yang Ryan: Like most fiction writers, I’d guess, I’m deeply curious about people’s lives. Whenever I take a taxi or am with a stranger for some amount of time, I want to know their story. And everyone has one.

I try in my historically-based fiction to be faithful to the feel of the moment or event. It takes really metabolizing lots of stories to get to a place where I feel like I have an accurate handle on how to tell the story in a conscientious way. I think I can tend toward didacticism, which I’m trying to work on!

You too are working with history in your fiction. I’m curious what your process looks like for bridging from history to story.

Sze-Lorrain: I did begin by “bridging from history to story”. . . until I gave up the idea of connecting one to the other. Instead, I invented aligned “realities,” scenes with specific moments of emotional honesty in relation to the characters and mixed them with history. Does this make sense?

Characters don’t formulaically become more “real” or credible once embedded in a historical setting. Quite the contrary: they could come across as more “fake,” worse, kitsch? I’m interested in characters in connection with their humanity, their sense of “the other.” How do they respond to strangers, newcomers, or someone “different” from themselves, for example? We should all live more authentically: thrive not to be twisted by societies, not to practice sanitized communication, nor construct images of ourselves, project them to others, then live by them and define it all as “reputation,” etcetera. In short, people who try to be bigger than who they really are.

The heroines in my fiction are rather intact in their emotional lives. They are pacesetters who take care of one another. I would like to believe that most women in these stories exercise spiritual freedom but never at the price of one another. They manage because of conjunctions and historical circumstances. Yet they don’t live in their own times. Not always. They might be ahead of what comes next and this in spite of their ordinary lives. That’s where the drama grows. I think of the Chinese saying, Times create heroes. Our world needs more people who live by principles, not interests or power.

Yang Ryan: I appreciate that formulation of starting with emotional honesty. I also appreciate that your heroines are “intact in their emotional lives.” That is so graceful. The emotionally chaotic woman is too common a trope that gets taken for granted.

I apologize in advance for this question, but I’m endlessly fascinated by the working habits of writers. You said you don’t believe in habits. Does that go for your writing practice as well?

Sze-Lorrain: I need a room to write or read. I read newspapers, write longhand. Beyond that, I don’t have any requirements. I lose patience with magazines that feature photographs about writers’ “rooms.” They claim to peek into artists’ private lives. Sounds more like an ad or a product, no?

As you said, writing is a practice. It has a non-material pursuit. I try to be rid of the image of writing or being a writer. I used to need silence. Now I write whenever possible. Once I get the sense of being trapped by a habit or comfortable routine—especially when “it works” more than once—I break it. I don’t shun discomfort: how else to improve, let alone invent, transform? You get stuck with the tyranny of production, sucked into a mindset based on accomplishment, instead of working through conflicts or differences. So yes, I don’t write according to a schedule or goal. It doesn’t mean deadlines aren’t helpful. I’m mentioning the fact that I make sure to stay powerless in the face of the unknown creative act. It’s another way to think young.

Yang Ryan: I’m learning so much from this conversation. I’m so intrigued by the idea of being “trapped” by routine. My whole writing life, I feel, has been about trying to establish a routine, failing, and feeling bad about it. Maybe I should lean into it instead.

Sze-Lorrain: You’re a busy working mother. And I apologize—for the obvious: is writing a challenge these days? What about your reading life?

Yang Ryan: Motherhood has definitely changed my relationship to writing, especially when I started having to pay someone (a babysitter) in order to have time to write. I did get pulled into a feeling that each writing session had to be “productive,” and that whatever I was working on had to be “worth” the time/money spent. So writing is a challenge, but the poet/novelist Hala Alyan said she was able to write her novels in daily thirty-minute chunks, which I found inspiring and accessible. Accessible goals!

What about publishing? How have you found the publishing experience, especially now that your debut novel is out? Most of my writer friends have not followed the traditional “query, agent, publisher” route. My first book was published by an independent local press—so local that I was stuffing publicity envelopes in my editor’s living room. It happened to be reviewed in an industry blog, where an agent read about it and contacted me. We’ve worked together since. Before that, it was rejection after rejection from agents, and then a year with an agent who would not respond to my messages. A circuitous path!

Sze-Lorrain: Circuitous is just the right word. I find strength in the creative life because the business of art, as you said, is another cuisine. I started working on my first story back in 2004. It seems yesterday but it isn’t. I try to take things one at a time. Every book has its own life. I think we are in for a long crazy ride.

If you’ve enjoyed reading this article, please consider making a donation. Your donation goes towards paying our contributors and a modest stipend to our editors. Singapore Unbound is powered by volunteers, and we depend on individual supporters. To maintain our independence, we do not seek or accept direct funding from any government.

‘Style, tone, and form aren’t just decoration—they’re the architecture of meaning... A plastic chalice cannot hold sacred wine.’ – an essay on meaning-making by Chadawan Yuddhara.