Getting Up to Fight

By Jonathan Chan

Review of Diaries of a Terrorist by Christopher Soto (USA: Copper Canyon, 2022)

-

Content warning for sexual violence.

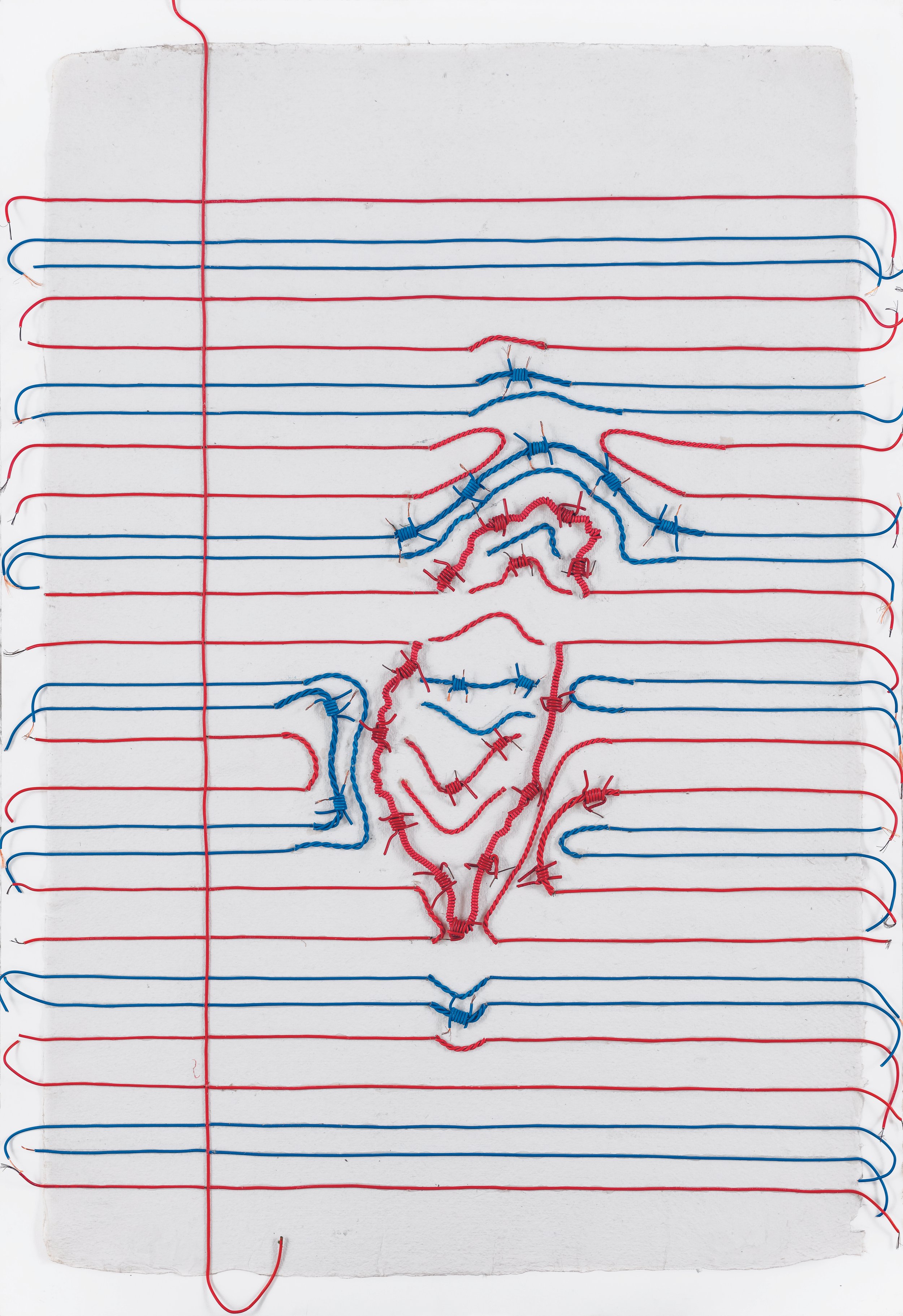

Reena Kallat - Ruled Paper (red, blue, white) (2022), Electric wire on deckle–edge handmade paper, 43 in x 31 in/109 cm x 79 cm each

Image description: Red and blue electric wires are arranged on a piece of white paper. The lines created by the wires resemble lines on a piece of ruled notebook paper. One red wire runs down the left of the page, forming a margin line. Towards the middle of the page, the wires distort and form patterns that interrupt the continuous straight lines. The patterns resemble fragments of barbed wire.

Back when I lived in New Haven, a sense of guilt would sometimes gnaw at me. I decried the conditions that led to shootings and police brutality but also took comfort in the security accorded by the city’s police, or rather, by the city’s being over-policed. Surveilled by state, city, and campus police, New Haven’s divisions were clear: protection fell along the lines between its transient and permanent residents. Mortality rates differed drastically between neighbourhoods, sometimes streets, and often on the bases of race and class. At the church I attended, the pastors had a fully formed liturgy for homicide, a way of memorialising and grieving the many lives, often young Black men, taken by gun violence in areas far from university campuses. I thought often about James Baldwin’s adage that ‘To be a Negro in [America] and to be relatively conscious is to be in a state of rage almost, almost all of the time.’ The seeming intractability of a ubiquitous yet intimate violence felt like something I could not escape, no matter where I was in the country.

These tensions that come from living under such conditions of rage are central to Christopher Soto’s poetry collection Diaries of a Terrorist. Soto is a Salvadoran poet, activist, and professor. In addition to his teaching ethnic studies, Soto has worked to end the separation of migrant families with Writers for Migrant Justice and capital punishment with Equal Justice USA. All of his roles cohere in the concerns of his poetry – police brutality, the cruelty of border regimes, mass incarceration, prison education, and how all of this interacts with being queer and Hispanic in America.

The through lines connecting Soto’s poetry and advocacy are consistent, focused as they are on dismantling structures of carceral capitalism. It is unsurprising to find scholar and poet Jackie Wang among those listed in his acknowledgments. The styling of Soto’s collection as the Diaries of a Terrorist directs attention to how the idea of a ‘terrorist’ is defined in the United States, denouncing the rhetorical embellishments that have imprisoned individuals and riven communities.

The collection, divided into four sections, moves between the United States and other locales, between indictments of prisons, tributes to queer communities, and recollections of American intervention in El Salvador. Although Soto assumes both a local and a global perspective toward carceral regimes, his most striking poems focus on police brutality in the United States. The collection’s first poem, ‘Meteor Shower // Or Where The Sky Skid Its Knees’, dedicated to ‘Tony’, is an unsparing initiation into Soto’s contention with violent policing. It begins:

Police killed our neighbor // On his

Doormat // Fifty footsteps from his bed

The bullet’s auburn cologne // Sprayed over him &

After the first shot // There were fireflies stumbling

Soto’s control of tone and pace is masterful; the caesura of each line, indicated by backslashes, and the careful placement of line breaks land each phrase with force. Capitalised words accentuate the fragmentary nature of each phrase. Violence breaks into the community, into domesticity, with images of the home tainted by the ‘spray’ of a ‘bullet’s auburn cologne’. Soto captures not only the crack and echo of a gunshot but also its olfactory residue. The evocation of ‘fireflies stumbling’ emphasises disorientation, the shattering of residential peace. Instinctively, the speaker ‘[falls] to the floor’ and then ‘Into the basement’. Seeking refuge, the speaker describes:

We struck a match across our face // To light the room &

Terror was scribbled on us // Is this war or genocide

The ambulance lights // Pirouetted like ballerinas

A different man was mourning on the street

Violence percolates down to the most intimate level. Terror resides not in anarchist violence that aspires to destroy the state, but rather in the state itself, in its brutalisation of ordinary communities. The questioning, ‘Is this war or genocide’, evokes the shallow rhetoric of the ‘war on crime’ or ‘war on drugs’, slogans activated in American political discourse over the last 30 years that have underpinned the militarisation of the police. These slogans often code violence directed against Black and brown communities. One remembers the beating of Rodney King, the murder of Breonna Taylor, the suffocation of George Floyd, and, most recently, the brutal killing of Tyre Nichols. Sudden intrusions of beauty, such as the image of the lights that pirouette ‘like ballerinas’, stand alongside a man ‘mourning on the street’. Soto’s startling contrasts bring to mind the cruelty in Ocean Vuong’s poem ‘Telemachus’, or the sorrow laced through Ilya Kaminsky’s poem ‘In a Time of Peace’. The panic and fear of Soto’s speaker conclude the poem: ‘Fuck not again / Who’ll protect us // From police // If not ourselves’.

Reena Kallat - Ruled Paper (red, blue, white) (2022), Electric wire on deckle–edge handmade paper, 43 in x 31 in/109 cm x 79 cm each

Image description: Red and blue electric wires are arranged on a piece of white paper. The lines created by the wires resemble lines on a piece of ruled notebook paper. One red wire runs down the left of the page, forming a margin line. Towards the middle of the page, the wires distort and form patterns that interrupt the continuous straight lines. The patterns resemble fragments of barbed wire.

The poems in the collection’s first segment circle the terrifying domesticity of police violence. In ‘Police Shot A Field of Daises’, the speaker remarks, ‘We had a panic attack while driving to work’, and ‘We kept having night-errors’. In ‘Chandelier Hangs in the Shape of an Octopus’, the speaker describes, ‘His mother was shattered & / Lighting candles at the vigil’. In ‘A Beautiful Day in the Psychiatric // Garden’, the speaker remarks, ‘It’s so American // The constant grieving of violets / Blooming state violence’. Violence manifests in the psychic wounds and scars of the speaker’s community, the permanent disfiguration of families, and the beleaguered resignation of continuous grief. In these verses I hear echoes of Amiri Baraka and Danez Smith. Soto’s poems tend to move toward the surreal when forced into a narrative corner: ‘Heaven never floated so far’, concludes ‘Police Shot a Field of Daisies’, and ‘Would shootings cease / If we shaved our brows to sew a coat’ closes ‘A Beautiful Day in the Psychiatric // Garden’. One imagines this as a response to trauma, the imagination’s pivot toward either serenity or desperation, the flight triggered by the trap of violence in one’s own neighbourhood.

Soto moves from police violence to the afterlives of incarceration in the extended sequence ‘The Children In Their Little Bulletproof Vests’. Soto seems to speak autobiographically, describing a ‘We’ who prepare ‘Poems / For incarcerated boys / Ages 15 to 19’. The poem proceeds as a fragmented stream of short lines, establishing scenes within ‘The detention center’, embedding the boys’ own words:

The teaching of poetry to young prisoners reminds me of both the listlessness and the great hope in Reginald Dwayne Betts’ Felon (2019). Yet, unlike Betts, Soto’s speakers do not mention the salvific promise of poetry amidst incarceration. Rather, the long poem accords Soto the space to reflect on the positionality of his poem’s speaker, an ostensible poetry teacher who must wash ‘Rustic Red paint from / [their] nails’ and exchange ‘black dress / For slim blue jeans’. They must do so to present themselves as respectable educators proximate to ‘State power’. Yet they also reflect on their own experiences of being arrested ‘aged to 15’. The poem weaves between the apathy of an inmate named Julian, no longer ‘afraid of death’ and ‘in solitary against / His will’, and the intergenerational abuse that culminates in the speaker’s own crimes:

Meanwhile, Julian is released from the detention centre ‘On probation / With an ankle monitor’, prompting a comparison with the state’s tracking of undocumented immigrants:

Soto unspools a history of racialised surveillance embedded in carceral and immigration regimes in the United States. The logic of bestialising Native peoples extends to the treatment of South American migrants, which also echoes the rendering of Black slaves as subhuman. A ‘History of human zoos’, inhabitants captured for white dominance, consumption, and control. Soto’s use of short lines creates a sense of cautious introspection and awful realisation. A sense of stagnation prompts a linguistic breakdown:

Lapses in spelling and grammar, and the segmentation of phrases and words into constituent elements and homonyms reveal a short-circuiting of the speaker’s thinking. Carceral regimes rely not only on control within prison systems but also on control on the outside.

In his third section, Soto turns his attention to manifestations of police violence beyond the United States. He pivots from violence at the American border to violence abroad. In ‘The Terrorist Shaved His Beard’, Soto performs an act of etymological experimentation: does terrorism derive from ‘tierra’, Spanish for land, or ‘err’, Greek for incorrect, or is it close to ‘terremoto’, Spanish for earthquake? Soto’s speaker conjugates terrorism into ‘terrorizing’, saying, ‘For example // On this land // Our People were / Terrorized by police // By ICE’. Here, Soto demonstrates the contradictions baked into the term ‘terrorist’ and the thin justifications behind state violence.

Reena Kallat - Ruled Paper (red, blue, white) (2022), Book, Electric wire on deckle–edge handmade paper, 43 in x 31 in/109 cm x 79 cm each

Image description: A ruled notebook is flipped open and placed on a white shelf against an empty wall. Its pages are white with red and blue lines, resembling four-lined pages used by students to practice cursive writing. On the notebook’s right page, lines in the middle of the paper distort and interrupt the continuous straight lines, forming patterns that resemble barbed wire.

The poems that follow, however, demonstrate the limitations of Soto’s imagined ‘We’. In ‘To Blow on the Horns of a Bull’, for instance, Soto pays homage to Dareen Tatour, who uploaded ‘a poem’ on ‘YouTube of Palestinians’ and flung ‘rocks at Israeli soldiers’. By describing the ‘electronic superhighway’ on which Palestinian activists rode before being ‘blockaded by // An Israeli Checkpoint’, ‘hyperspace occupied’, Soto adroitly blends Palestinian displacement with Internet censorship by the Israeli state. The poem pleads, ‘Google search Nakba’. The ‘We’ here ostensibly refers only to supporters of Palestinian liberation and statehood.

In another instance, ‘In Support of Violence’, Soto’s ‘We’ refers to the ‘Two hundred Indian women’ who ‘Murdered their rapist on the courtroom floor of Nagpur in 2004’. Soto writes:

The poem underscores a justification of retributory violence that levies proportionate harm against a rapist of two hundred women, a perpetrator of vile and egregious assault. But it is hard to square this justification with Soto’s anti-carceral politics. In instances of such wicked crime, what forms of redress are adequate? Can the violence of incarceration be substituted so swiftly for the violence perpetrated against the women?

One wonders whether the coalescence of liberatory politics across geographies and traditions also enacts a kind of flattening. Each situation bears its own histories of patriarchal, racial, and militaristic entrenchment and oppression. One wonders if the ‘We’ who stand for an end to violence against women are necessarily the same ‘We’ who stand for Palestinian freedom. Expressions of solidarity are vital, but I hesitate at the presumption that this solidarity can be uniformly expressed. Does Soto presume every ‘we’ to be suffering under the same conditions or fighting the same oppression? Can an equivalence be identified between these poems illustrating very different conditions of violence? What claim does Soto have to declaring himself a part of each ‘we’ he describes?

As Soto brings readers on a journey through liberatory movements across the world, it is fitting that his final poem, ‘Then A Hammer // Realized Its Life Purpose’, skews closer to his own life. ‘The personal is political’, argued feminist activist Carol Hanisch. Styled as a round-of-five boxing match, the poem brings readers through an odyssey of parental violence and childhood trauma, of pet dogs being abused, and of personal anger, combativeness, and valiant defiance. Soto’s speaker turns to boxing to ‘let go of anger’, an alternative to punching ‘our ribs before sleep’ to ‘make our skin tougher’ so ‘we wouldn’t feel father punching us’. The line ‘Jab // Lead Hook // Cross // Duck // Jab’ mirrors the pugilistic poetry of SJ Fowler. The speaker’s friend says, ‘He was fighting bigotry & hate / He was fighting concepts & not people’. The speaker ‘contemplated Mexican Brutalism // & Luis Barragan in a luxury gym’. The speaker declares, in the aftermath of 9/11, ‘if America // The biggest bully’ could suffer such an attack, ‘Then how could we ever think we were safe’. And by the poem’s conclusion, which also functions as the collection’s conclusion, Soto delivers his rallying cry:

Although Soto’s work is sometimes burdened by its ambition, it nevertheless rises to its promise of revolting against police brutality. One sees in Soto’s work a clear delineation of the violence that patterns and structures so much of contemporary life in the United States and elsewhere, one paralleled by the histories of American imperialism and interventionism. Soto transposes liberatory politics into poetry; his work is a form of consciousness-raising, an exhortation to witness how the political must proceed from the personal. These calls for solidarity seem timely, especially as the United States continues to reel from carceral violence. Reading Soto’s work, I was reminded of the calls of two civil rights leaders: first, Fannie Lou Hamer’s injunction that ‘nobody’s free until everybody’s free’, and second, Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.’s proclamation that ‘Injustice anywhere is a threat to justice everywhere. We are caught in an inescapable network of mutuality.’ Soto’s message to all who can rise against state violence is clear: “Get the fuck up & fight”.

Reena Kallat - Ruled Paper (red, blue, white) (2022), Book detail, Electric wire on deckle–edge handmade paper, 43 in x 31 in/109 cm x 79 cm each

Image description: A ruled notebook is flipped open and placed on a white shelf. The notebook’s pages are white with red and blue lines, resembling four-lined pages used by students to practice cursive writing. Towards the right edge of the right page, the lines start to curve and bend, interrupting the continuous straight lines. The lines form patterns that resemble barbed wire.

Jonathan Chan is a writer and editor. Born in New York to a Malaysian father and South Korean mother, he was raised in Singapore and educated at Cambridge and Yale Universities. He is the author of the poetry collection going home (Landmark, 2022) and Managing Editor at poetry.sg. His essays and reviews have appeared in Quarterly Literary Review Singapore, The Foundationalist, and Jom Magazine. More of his writing can be found at jonbcy.wordpress.com.

*

Reena Saini Kallat was born in 1973 and lives in Mumbai. Her work is exhibited at institutions including the Museum of Modern Art (MOMA), New York; Migros Museum of Contemporary Art, Zurich; Tate Modern, London amongst others. Her work is in the collection of Musee de Beaux Arts, Ottawa; Art Gallery of New South Wales, Sydney; Arnhem Museum, Netherlands; Cincinnati Museum, Ohio; Manchester Museum, UK; National Taiwan Museum of Fine Arts, Taichung; Vancouver Art Gallery, Canada; Sharjah Art Foundation, UAE; Burger Collection, Hongkong; Kiran Nadar Museum of Art, New Delhi; Bhau Daji Lad Museum, Mumbai; National Gallery of Modern Art, New Delhi.

If you’ve enjoyed reading this article, please consider making a donation. Your donation goes towards paying our contributors and a modest stipend to our editors. Singapore Unbound is powered by volunteers, and we depend on individual supporters. To maintain our independence, we do not seek or accept direct funding from any government.

In Taiwan Travelogue, ‘twinned souls… are at once lost, but also found, in translation.’ A review by Eunice Lim.