#YISHREADS September 2025

By Ng Yi-Sheng / @yishkabob

This month’s column has been a long time coming! You see, I’ve previously devoted articles to SFF by writers from the Chinese and Indian diasporas [1]—but that leaves out one central racial label from the Singaporean ethnic trifecta. [2]

What about Malays? They’re the indigenous people of our country, comprising 13.5% of our citizenry. Furthermore, there’s been a growing wave of Singaporean Malay speculative fiction, in both English and the Malay language, as identified by Nazry Bahrawi in his afterword to his anthology Singa Pura-Pura. [3]

But as soon as we start talking about a global Malay diaspora, things get tricky. The word “Malay” means different things in different communities. A person of Javanese descent would be classified as Malay in Singapore or Malaysia, but probably not in Indonesia (where “Malay” applies specifically to certain groups originating in Sumatra). Many Filipinos identify with the term because of their national hero José Rizal’s championing of a pan-Malayan union across island Southeast Asia—but most Singaporean Malays don’t see them as part of a common community, unless they’re Muslim.

And of course, Malays simply aren’t as ubiquitously scattered across the planet, as Chinese and Indians/South Asians are. Sure, there are the Cape Malays of South Africa, the Sri Lankan Malays, the Javanese Surinamese and the Moluccan Dutch. Still, we don’t have a global Chinatown situation where you can expect to find emigrants and expats in every major metropolitan area—let alone authors of fantasy, science fiction and horror.

Regardless: there are six nations in Southeast Asia alone with substantial populations who’d be widely considered Malay: Singapore, Malaysia, Indonesia, Brunei, the Philippines (especially Mindanao) and Thailand (especially Patani). Among the first four of those, it’s easy enough to track down examples of English and translated works of speculative fiction. And so what if no-one’s talking about an international movement of Malay (or Malay-ish?) SFF? If the discourse actually takes off, hey, you heard it here first!

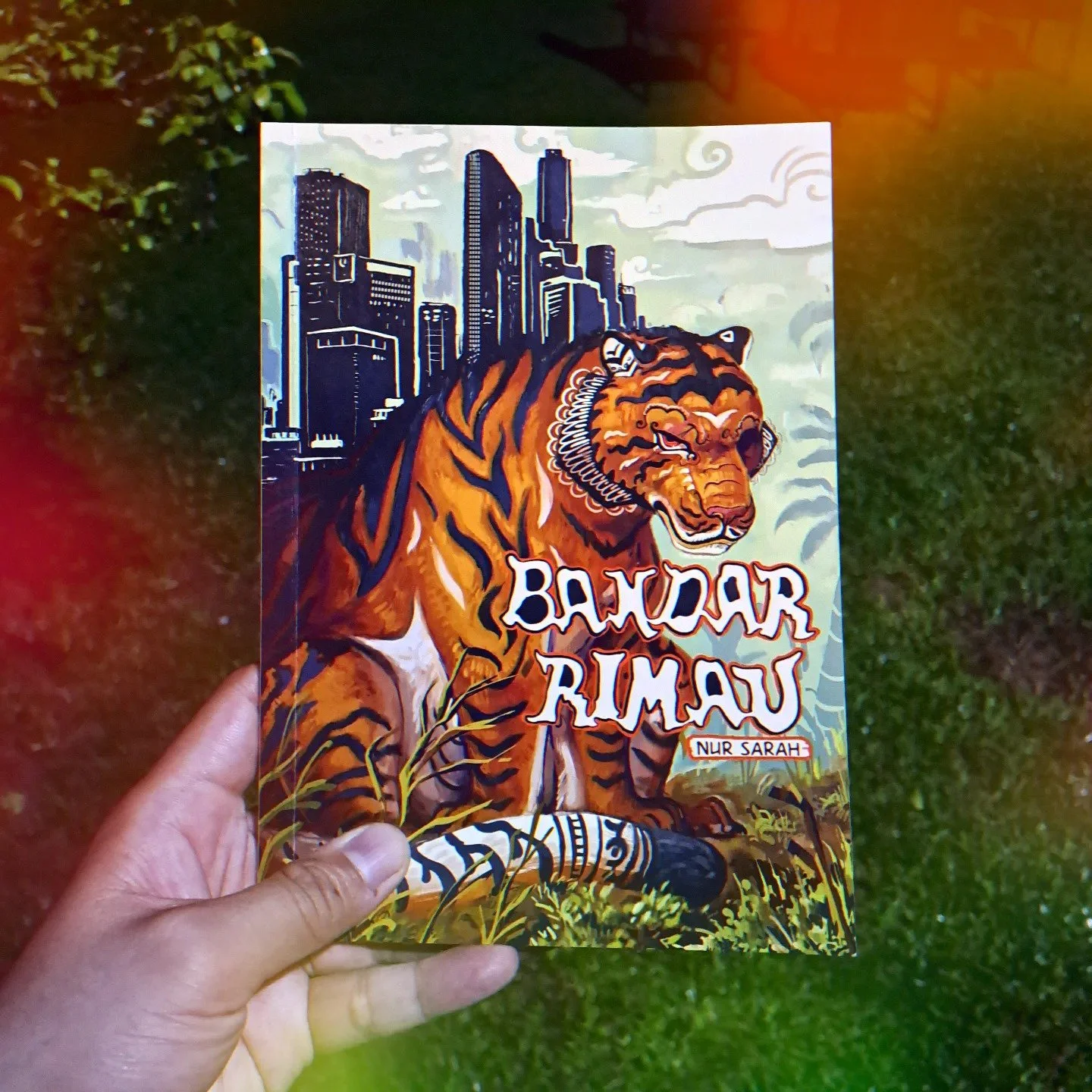

Bandar Rimau, by Nur Sarah binte Abdul Wahid

Self-published, 2023

First off, we’ve got a fantasy comic zine, exploring the tensions and sorrows of Singapore’s Malay history. There’s not much of a plot, to be honest. Sazali, an aging weretiger, claims our country was misnamed as the “Lion City”, because our first king Sang Nila Utama didn’t see a lion, but a tiger. Then, he decides to appear in Parliament in animal form to argue for the nation to be renamed “Bandar Harimau”, or “Tiger City” in Malay, until he’s persuaded not to by his friends.

The cool thing, however, is that Nur Sarah’s art is truly stunning, being a combination of vivid vignettes based on wayang kulit and wayang beber aesthetics, as well as the contemporary urban world of HDB lift lobbies and sarabat stalls. Sazali’s friends are magical beings themselves: Yuna’s a crocodile in a voluminous green baju and Kasturi’s a mousedeer in a batik jacket—character design sheets at the end explore this more explicitly. Plus, their conversation bears witness to the sense of historical erasure that all Singaporeans, but especially Malay Singaporeans, have experienced: the demolition of kampungs, separation from Malaysia, disdain for Malay language and culture. Sazali taps on a deep wellspring of indigenous rage when he says, “We play nice for what? Respect? Please lah. We gave them our land. Our food. Our lives! And in return we get what? Nothing!”

Furthermore—and I suppose I’m only alert to this because Nur Sarah uses they/them pronouns—I believe there’s a queer subtext running through the tale. Sazali speaks of running away from his family and his kampung; his desire to come out is weighed against the magical beings fears of persecution and ostracism; and the group’s somewhat anti-climactic resolution is that they’ve got to organise sharing workshops and events: a strategy applicable to both queer and indigenous recognition.

Feels like a set-up for a sequel, but I don’t see one on Nur Sarah’s Ko-fi page. [4] Still, you can visit to buy this zine in print or pdf form, as well as their new comic series Haunt Out.

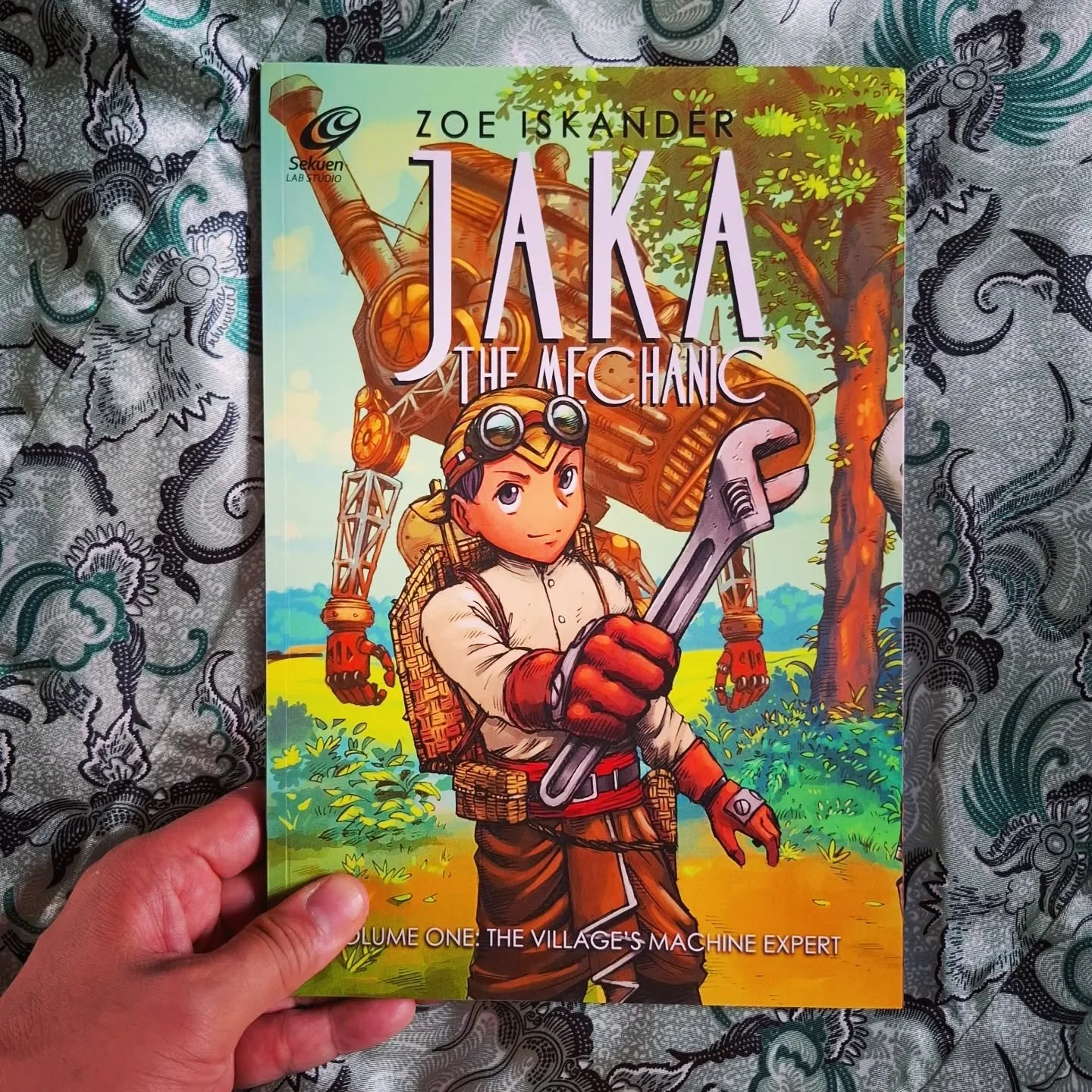

Jaka the Mechanic, Volume 1: The Village's Machine Expert, by Zoe Iskander [5]

Translated by Budi Iskandar

Sekuen Lab Studio, 2024

Presenting the first of an ongoing steampunk comic series set in an alternate 1920s Dutch East Indies, where colonialism is enforced and resisted through the weaponization of giant mechas! Cool, huh? (By the way, for the purposes of this review I’m gonna cheat a little and also cover the contents of Volume 2: De Helden Compagnie and Volume 3: The Javanese Doctor.)

Beyond the rock-em-sock-em action sequences and the plucky heroism of Jaka, our 14-year-old eponymous protagonist, there's some quality research and thought that's gone into this story. There’s the standard narrative that a tech gap separates Europe and its colonies, which is why the colonised have to learn to wield tech on their own terms—but we're also seeing the historically real opposition among the villagers to embracing the enemy's tools and collaborating with sympathetic Europeans. Furthermore, there's an embrace of local mysticism as a counterweight to science: Jaka’s love interest Aisha is adept at healing magic, and multiple parties are searching for heirlooms to harness the ancient powers of Nusantara—also a feature of nationalism, as ideologues (e.g. the Theosophists) claimed that colonised nations had spiritual power which the West could learn from.

Furthermore, this is a multiethnic story: though Jaka’s Sundanese, Aisha is part Acehnese, and there are Dutch, English and Chinese characters too—not to mention dialogue in Sundanese, Javanese, Hokkien and Dutch. (The main text is translated from Bahasa Indonesia, but its disappearance is oddly appropriate, since that hadn’t yet been adopted as a lingua franca.) We have modern women wielding weaponry—super amusing to read that the jetpack-riding Fientje van Hoff was inspired by characters in Pramoedya Ananta Toer's Buru Quartet and Neon Genesis Evangelion!—and multiple characters are disabled, using steampunk wheelchairs and prosthetics as aids to their badassery.

All of which adds up to a story of revolution that isn’t just good-guys-vs-bad-guys, as Jaka’s sympathies shift between political viewpoints and taboos and different groups battle for different interpretations of progress. No closure, I’m afraid—the untranslated series is currently up to Volume 8.

Strange to read this now, when Indonesia’s going through a new wave of political turmoil and popular rebellion. Much of the action takes place in Bandung, with afterwords explaining the cartoonist’s meticulous recreation of buildings in the old colonial centre—and it’s the same city where police are attacking student protesters today. [6] Merdeka isn’t a noun; it's a verb.

Tales from Cabin 23: Night of the Living Head, by Hanna Alkaf

HarperCollins, 2024

Another horrific hantu tale from this acclaimed Malaysian middle-grade author, again exploring how the power of sisterhood and family can defeat the darkest forms of evil. [7] This time it's focused on the penanggalan, that fascinating vampiress whose head is able separate from her body, flying around the forests with her entrails flapping behind her—which is really cool, cos there’s a wealth of Malay monsters that we don’t feature in pop media enough. (Can’t always call on the pontianak, y’know!)

What’s really wonderfully unheimlich about this tale is that the horrors aren’t just external (as you might think from the cover)—the penanggalan, Kak Ayu, is the adult sister of the protagonist Alia, and she’s just moved back home after running away, plus she’s haunting the family by actually being helpful (e.g. ruining the school’s Arabic exams with ink cos Alia hasn’t studied, tearing up her enemy's homework, scaring the bejasus out of the disrespectful students that their dad lectures in university). So Alia’s torn between familial closeness and deep suspicion of evil, especially because Kak Ayu literally looks super-hungry whenever someone starts bleeding.

And again, I can't help wondering if there’s a queer metaphor here. Ayu’s this outcast—it’s never specified why she ran away or what bad things she did that led her into the world of black magic—but she’s welcomed back into the arms of her parents, who really do love her. No conflict between that and the fact that they're practising Muslims. (When Alia utters the “Ayat al-Kursi”, it doesn’t faze her.)

Furthermore—SPOILER WARNING!!!— Alia eventually realises that her sister’s good, mostly cos they have to gang up against genuinely evil spirits who start possessing the town. Yet at the end, Ayu realises it’s her presence that’s leaking jinn and pembalang into the mortal world, so she leaves again to teach English in the Philippines, which does kinda provoke the question of whether she's just gonna cause another ghost outbreak over there. SPOILERS END.

How should we read this? Apparently, deviance + unconditional love doesn’t = integration. Like it or not, she’s toxic, and can only be trusted to send warm emails from afar. Reminds me of the dictum that horror is fundamentally a conservative genre, where the status quo must be restored, or else the consequence is disaster. Nonetheless, love remains, even if you can’t change the laws of the universe to keep people together.

One final note. As is tradition for the Tales from Cabin 23 series, we’ve got the framing device of an American sleepaway camp (100% populated by Malaysians in this tale, which feels unlikely?). And the epilogue surprisingly leaves us with fear and doom rather than the redemption which Hanna usually gives us. Don’t really think that helps the logic of the story, but maybe it’s a necessary condition to be included in this multicultural lineup of ghost stories—i.e. folks in Utah and Nebraska will get to have nightmares about the penanggalan, just like we may. That's a trade-off I’m willing to accept!

Weird Kid, by Greg Van Eekhout

HarperCollins, 2021

I got to meet this author in San Diego—Clarion's got a couple of his middle-grade SFF novels in the printer room!—and he’s Dutch-Indonesian-American, i.e. descended from Indonesian Eurasians, whom I’ve heard of as a historical group of folks who pioneered the sarong kebaya, etc, but haven’t encountered much as a contemporary community.

His middle-grade novel follows the character of Jake—also explicitly Dutch-Indonesian—who’s starting middle school in an Arizona suburb with the secret that he's a shape-changing alien, struggling to control his powers as he hits puberty. And he gets himself in all kinds of shenanigans—making friends with his schoolmate the ridiculously talented superhero-wannabe Agnes, investigating mysterious sinkholes and shadowy government agencies, playing experimentally electrical guitars and arguing with his worried parents, who'd much rather he be home-schooled to keep his secret safe.

And in the end, everything ties in together with a conclusion so satisfying and heart-wrenching that it had me tearing up on the San Diego trolley. A lot of which is tied to this revelation—once again, SPOILER ALERT!!!— that he’s part of an alien hive consciousness in the form of a gelatinous goo that fell from the Crab Nebula thousands of years ago, dispersed and unable to return cos their planet’s been destroyed. Van Eekhout told me it’s his way of retelling the Superman mythos, but it’s also the diasporic experience, isn’t it? Learning who you are and embracing your heritage doesn’t mean you can go back. SPOILERS END.

True Ghost Stories of Borneo, by Dr Aammton Alias

CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform, 2018

Back to horror! But this time, instead of fiction, we’re talking about non-fiction, specifically the seven-volume collection of supernatural anecdotes, now retitled Real Ghost Stories of Borneo, possibly to avoid confusion with Russell Lee’s True Singapore Ghost Stories.

However, this first book of the series isn't all that much like its Singaporean counterpart. Our own 1989-onwards series presents itself as a cosmopolitan nationwide survey, often urban, featuring brief accounts of encounters from different racial/religious traditions, with Lee himself commenting after each tale in his own voice, providing educational sections on werewolves and UFOs and other global paranormal hocus pocus. This volume, on the other hand, is deeply personal—many are Aammton's own experiences, or those of his friends or named contributors, with only 28 entries in all—and tend to be deeply tied to the indigenous horrors of the rainforest and the wilds. Even when an unspeakable horror appears in a Chinese cemetery, it feels bestial, tropical, utterly native to this clime.

Though almost all the tales here take place within the national borders of Brunei, Aammton uses his intro to speak for the whole island of Borneo: Sabah and Sarawak in Malaysia; Kalimantan in Indonesia [8], explaining that they don’t really have this mania for the pontianak that folks in Singapore or Kuala Lumpur have, fearing instead the Orang Tinggi—these 40-foot tall lanky beings in the forest with ominously evil faces.

Sure, the creatures aren’t that alien to Singaporean readers: there are women in white; tutut (a version of pocong); Orang Bunian who steal away soldiers in the jungle (and there are so many soldier stories!); beliefs that spirits may be merely “playing” with you when they torture you for not apologising courteously enough when you piss in the woods; the logic that ghosts attack people who are “lemah semangat”, with not enough spiritual power, “tenaga batin”; the standard operating procedure of consulting an ustaz or laying charms (“guris”) outside the borders of your camp so evil can't intrude. But there’s also all these references to the witnesses falling back on their heritage—Aammton is part Kedayan; another friend he mentions is Iban—to understand what they’ve seen, and the final true ghost story is just a folktale about the gruesome origins of a being called the surung tarik. Supernatural with an emphasis on the “natural”: the horrors are part of the island's ecology, and must be respected, not conquered, if you want to survive.

All of which is made doubly uncanny by the knowledge that Aammton is a medical doctor, who talks about the annoyance of treating women with susuk embedded in their flesh and the flying witch ghosts whom all the patients complain about in a specific ICU ward! Yet I’d argue there’s also comfort here, to see a writer from another nation casually reflect that it's totally normal for a society to be high-tech, high-development and haunted.

Endnotes

[1] See, most recently, Ng Yi-Sheng. “#YISHREADS January 2025”. Suspect. 31 January 2025 https://singaporeunbound.org/suspect-journal/2025/1/31/yishreads-january-2025; also Ng Yi-Sheng. “#YISHREADS November 2024”. Suspect. 29 November 2024.

[2] Singapore’s government and society have consistently celebrated racial harmony by highlighting the country’s three major races, defined as Chinese, Malay and Indian—or occasionally four major races, with the addition of Eurasians.

[3] Nazry Bahrawi. “Malays Speculating Futures.” Singa Pura Pura. Ethos Books, 2021.

[4] “beet’s Ko-fi shop.” Ko-fi. https://ko-fi.com/beetbox/shop.

[5] A caveat: I’m genuinely unsure if Zoe Iskander would describe himself as Malay or of Malay descent, even after asking other Indonesians! Way too cringe to message him out of the blue to ask directly.

[6] See Yuddy Cahya Budiman and Stanley Widianto. “Indonesian police fire tear gas, rubber bullets at student protesters.” Reuters. 3 September 2025. https://www.reuters.com/world/asia-pacific/indonesian-police-fire-tear-gas-rubber-bullets-student-protesters-2025-09-02/

[7] There’s a strong parallel here to Hanna Alkaf’s The Girl and the Ghost, which I reviewed in Ng Yi-Sheng. “#YISHREADS May 2023.” Suspect. 26 May 2023. https://singaporeunbound.org/suspect-journal/2023/5/26/yishreads-may-2023

[8] A note from the Editor-in-Chief: I thought it necessary to jump in here to briefly discuss the place of Borneo in the ‘Malay world’. Indigenous liberation movements in both Malaysian and Indonesian Borneo strongly contest absorption into the ‘Malay world’ as the concept has been used to suppress their beliefs, traditions, and ways of life, and this continues to this day. This is important to keep in mind as we continue to discuss the parameters and ideas of the ‘Malay world’.

Ng Yi-Sheng (he/him) is a Singaporean writer, researcher and LGBT+ activist. His books include the short-story collection Lion City and the poetry collection last boy (both winners of the Singapore Literature Prize), the non-fiction work SQ21: Singapore Queers in the 21st Century, the spoken word collection Loud Poems for a Very Obliging Audience, and the performance lecture compilation Black Waters, Pink Sands. He recently edited A Mosque in the Jungle: Classic Ghost Stories by Othman Wok and EXHALE: an Anthology of Queer Singapore Voices. Check out his website at ngyisheng.com.

In Taiwan Travelogue, ‘twinned souls… are at once lost, but also found, in translation.’ A review by Eunice Lim.