#YISHREADS December 2025

By Ng Yi-Sheng / @yishkabob

Ah, Christmas! A season of Euro-American capitalist clichés: snowflakes and stockings, eggnog and plum pudding, jingling cashiers and sleighbells. Scratch that frosty surface, however, and you might notice a hidden set of tropical signifiers—wise men on camels, a little town called Bethlehem, a star in the East.

In other words, December’s a pretty good time to talk about books from and about the Middle East—or the MENA/SWANA region, if we wanna be a little less Orientalist with our labels. This is the birthplace of religions and civilisations, the site of medieval enchantments, and the flashpoint of all the contradictions of the 21st century: the riches of Dubai and Riyadh as well as the ongoing genocides in Gaza, the West Bank and Sudan. Lest we’re seduced by exotica, it’s also important to remember it’s a home to everyday folks, sharing the same petty triumphs and struggles that we do.

All this is captured in these recent reads of mine, including a Persian epic, an Egyptian comic, new short fiction from Yemen and an anthology of women’s poetry spanning five millennia. I’d hoped to feature writing by a Singaporean of Arab descent, but I couldn’t track one down: in the end, it felt more timely to include a collection of Singaporean essays on Palestine. The so-called “ceasefire”, which Israel violates with impunity,[1] is no reason to stop talking about the injustice of occupation. May the new year bring with it new hope for liberation.

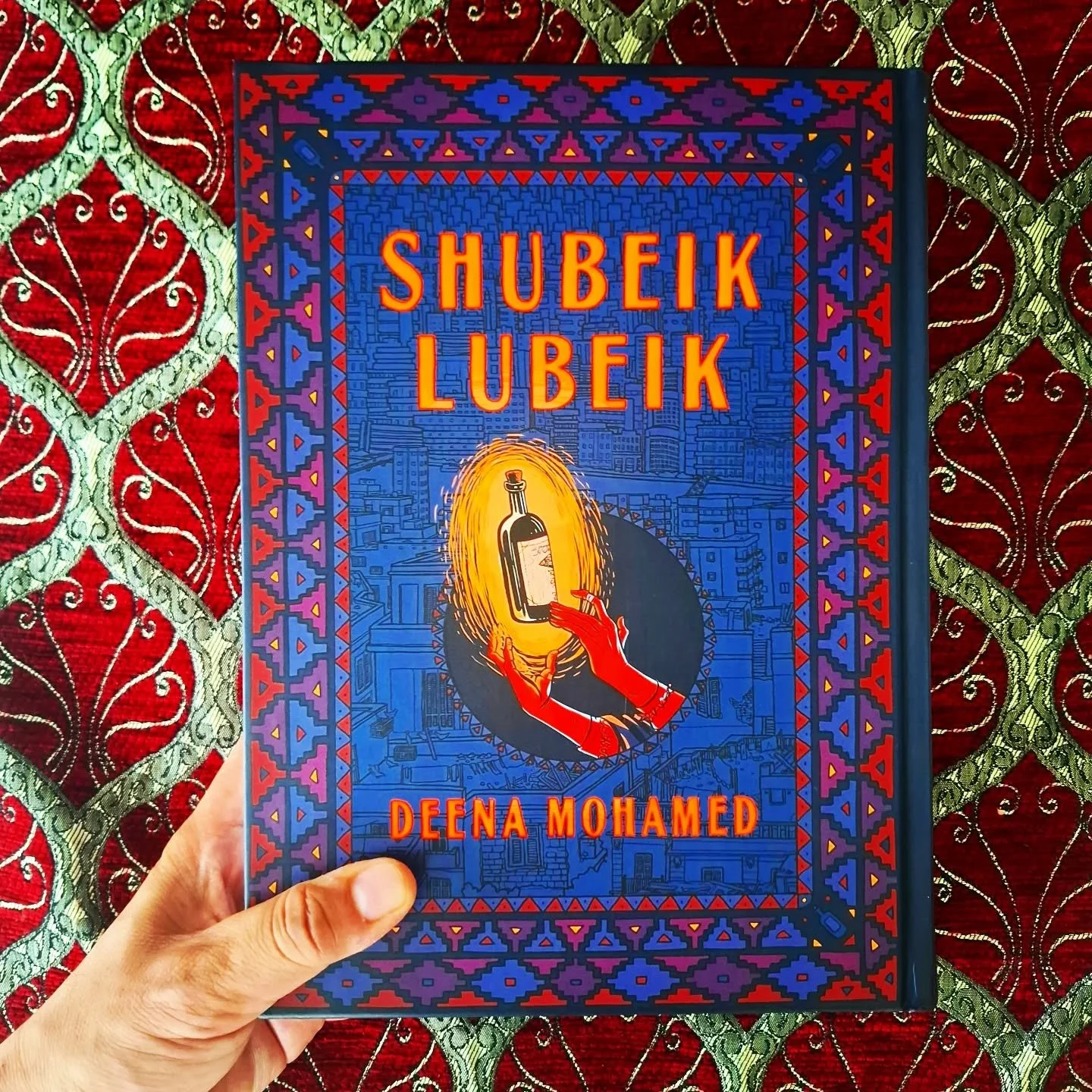

Shubeik Lubeik, by Deena Mohamed

Translated by Deena Mohamed

Pantheon Books, 2022

This really is a marvel of a graphic novel. It’s urban fantasy/magical realism, set in a world where wishes are real: they’re literally sold in bottles, divided into first, second and third class (the last of which tend to go horribly wrong), with a fair amount of worldbuilding invested in explaining how that plays into global politics, economy and Islamic theology—not to mention the oddness of everyday life, where there are talking donkeys in traffic and your neighbour keeps on acquiring dinosaurs.

However, the tales themselves—and yes, there are tales, cos this is a Thousand and One Nights-style matryoshka of a story—are intimate, centred on the lives of people in Cairo: a middle-aged Muslim convenience stall owner and his Coptic Christian customer, a poor cleaning woman and a rich nonbinary university kid. Through their tales, we get a portrait of contemporary Egypt: government corruption, deep income inequality, legacies of colonialism and tribal violence, internal migrations, domestic tourism to the pyramids and the beaches of Alexandria, and so much joy, heartbreak and healing. So you get this fusion of the everyday and the epic that makes you treasure your own existence.

There’s also this fascinating symbolism behind what commodified wishes represent: an obvious allegory of oil, the way they’re mined from formerly colonised nations, then refined and sold back to their citizens. But there’s something more, the way they’re declared as haram, like they’re the wisdom of ancient civilisation that’s been appropriated by other cultures. I’ll leave that to a grad student to write about!

By the way, I learned about this novel because the cartoonist spoke on a Singapore Writers Festival panel about self-translation: she wrote this in both Arabic and English, then convinced her publisher to print it from right to left, just like they do for manga. Pretty cool, huh? But then her French and German translators were confused about whether they should translate more faithfully from Arabic or English! That’s the kind of polysemous 21st century world we live in!

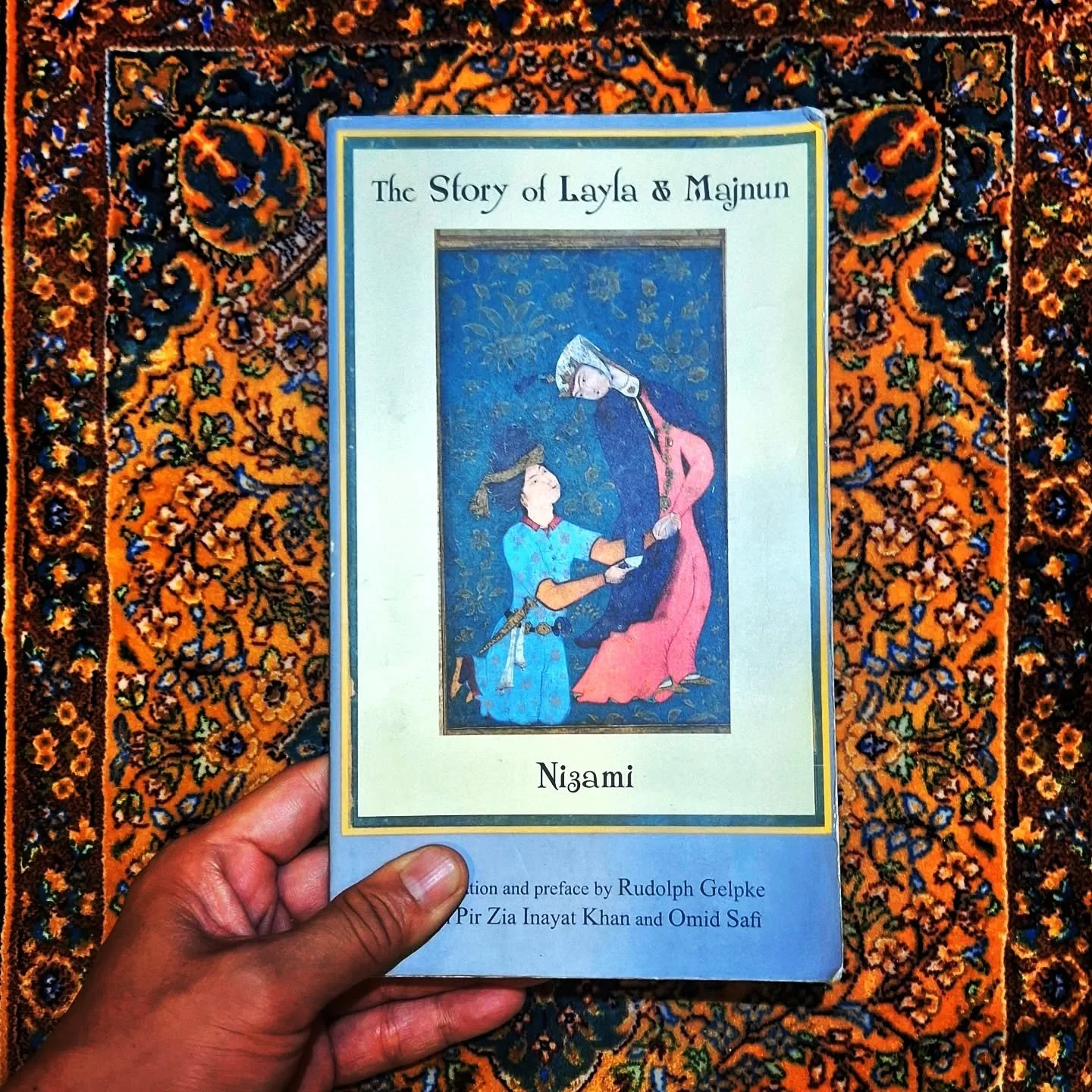

The Story of Layla & Majnun, by Nizami

Translated by Rudolph Gelpke

Sulūk Press, 2011

Let’s now go back to the 12th century to look at a Persian epic so famous, its characters are idiomatic as lovers. It actually served as the basis for Singapore’s first Malay language feature film in 1934![2]

Majnun is a genius poet gone mad with longing for Layla—literally, he starves himself to a skeleton, bashes his head against rocks and lives naked in the wilderness with beasts, though passersby are in awe of the verses he utters. Surprisingly, both are described as being wondrously beautiful in their youth, when they met in school (yeah, I was surprised it was co-ed, but these are Bedouin tribespeople in an early age of Islam?). Then Majnun goes nuts as soon as they start to have feelings for each other, and Layla’s dad forbids the marriage, cos who wants to be in-laws with a madman?

Shades of Romeo and Juliet—but the two don’t get to have a secret marriage. Layla just feels tortured as she hears his voice from beyond her tent, or when whispers of his poems get passed to her, and her dad actually marries her off to someone else, whom she doggedly refuses to sleep with, though the only time she has the gumption to run away, she keeps her distance from his hermitage, knowing the fire of his desire will burn her.

It’s easy to roll your eyes at her lack of agency, at the fact that while Majnun goes loco and causes his parents to die of grief, she doggedly follows the rules of patriarchal society. But she does get a voice: there are scenes where each of them exchange letters, and her words match his in beauty. And sure, it’s ridiculous that she dies a married virgin (not quite Love in the Time of Cholera), thus preserving her purity. But remember, Majnun dies a virgin too, supine on the mound of her grave, his animals watching in pity. There’s a final chapter in which Majnun’s follower Zayd has a dream of them united in heaven, but translator Rudolph Gepke didn’t think it was Nizami's original—it’s had to be reproduced here with a fresh translation by Pir Zia Inayat Khan and Omid Safi!

Basically, the point of all this is unfulfilled desire, which must remain frustrated so that it represents the impossibility of the union of the Sufi soul with God in the mortal world. Which I suppose is why they can't have a period of union like Radha and Krishna; why the two don’t go searching for each other like Panji and Candra Kirana—or is that a good excuse at all, since both parties are arguably representations of the soul and the divine, thirsting after each other? Complicating this is the fact that Majnun probably was a real person: the 7th century poet Qays ibn al-Mulawwah, and the outlines of his legend had already been established by the time Nizami got to it, making it a little harder to make shit up that transforms the set dynamic of the lover and the beloved.

My gay ass, however, is intrigued by the whole chapter where the chieftain Nawfal discovers Majnun, befriends him and promises to battle for Layla’s hand, thus restoring his health and beauty. He’s actually triumphant against Layla's dad but refuses to take the bride by violence (the idea of asking her directly doesn’t occur to him), thus motivating Majnun to take a permanent turn towards social deviance. But there’s this joy and tenderness among the two men, which, while temporary, gives me cause to ship them. Wonder what Sufi symbolism we can read out of that?

A note on the poetry. This is a prose translation, so this comes across mostly in layered metaphors about pomegranates and jasmine and wine (though the wine’s real; they weren’t teetotallers). Be warned, though: there’s some icky bits comparing the darkness of night and sorrow to the skin of Black people. Ugh.

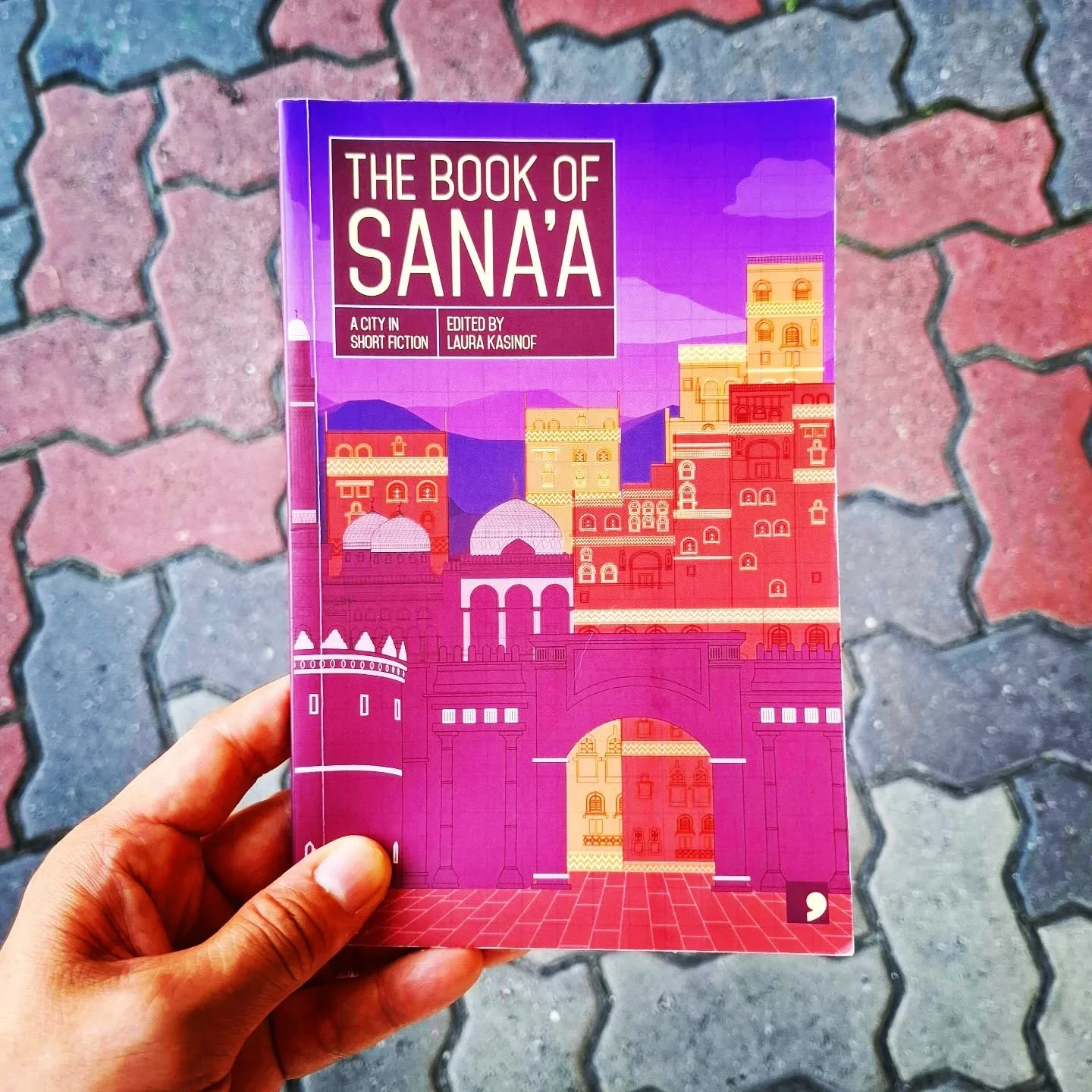

The Book of Sana’a, ed. Laura Kasinof

Comma Press, 2025

A gorgeous concept and cover—who wouldn’t want to own a jewel-toned paperback, purporting to condense the trauma and culture of a war-torn UNESCO World Heritage Site of a city in ten brief stories?

Truth is, however, the contents are a mixed bag. I know I’m supposed to be swayed by the poetical tour of the city’s landmarks in Rim Mugahed's “The Ruse of Sana'a”, to chuckle at the tale of survival in the chaos of civil war in Wajdan al-Shathali's “The Jacket”, to weep for the little sister shot by a stray bullet in Atiaf Alwazir's “The Road to Destiny”, but they kinda left me cold. (That last one is way too sentimental, and it doesn’t help that the kid’s behaving like a brat in the middle of a warzone.)

Maybe I just needed time to warm up, though, cos the middle stories work for me, especially Badr Ahmed’s “A Photo and a Half-Full Glass” with its surprisingly lyrical tale of a man mistakenly arrested in a democracy protest (his mum makes him wear a Jewish friend’s protective charm, and the secret police believe the Hebrew proves he's an Israeli agent). Same with the intensity of Gehad Garallah's “Questions of Running and Trembling” (though there’s always a tinge of cliché with stories of girls being oppressed by modesty wear) and Gamal Alsah’ari's Sana’a’s “Missiles” (also maybe a little overwrought, but someone should write from the POV of one of those married couples whose weddings get bombed), plus Afaf al-Qubati’s “The Girl of the Fountain” (for a change: a tale of peacetime.)

Plus, there’s spec fic here! Though perhaps we should call it allegorical satire: Hayel al-Mathabi’s “The General Secretariat of Speed Bumps” is just a way to poke fun at corrupt nepotistic bureaucrats, and there’s both deep sorrow and whimsy in Abdoo Taj’s “Borrowing a Head”. Then there’s Maysoon al-Eryani's “Shadows of Sana’a”: is it really about teenage jinn, or do they represent some minority I know nothing about? All these labyrinths of translation!

Classical Poems by Arab Women, ed. Abdullah al-Udhari

Saqi Books, 2024

Hmmm. I’d expected to love this book, but I honestly don’t think the translations are all that effective—the smattering of renditions from Khansa and Raabi'a al-Adwiyya, two of the most renowned poets of any gender in this tradition, left me cold.

It’s also iffy whether what we’ve got is an authentic representation of women’s voices. Sure, it’s amazing that volume harks back to the pre-Islamic era of the Jahiliyya (4000-BCE-622 CE), but the quotations from figures like Mahd al-Aadiyya, witnessing Allah’s cloud of destruction in the age of the Prophet Hud, or Afira bint Abbad, chastising her people for allowing a foreign king the droit de seigneur, feel more like fragments of legends, not unlike “Mirror, mirror, on the wall” or “I’ll huff and I’ll puff and I’ll blow your house down.”

Nevertheless, it is interesting to see a gathering of women’s perspectives, semi-fictitious or not (they’ve even included lines from Laila bint Sa’d al-Aamiriyya, the beloved of Majnun), revealing the surprisingly diverse roles they occupied: the political leader Fatima bint Muhammad, daughter of the Prophet; the country bumpkin wife Maisun bint Bahdal of the Umayyads; the warrior Laila bint Tarif and the slave-sexing singer Ulayya bint al-Mahdi of the Abbasids... and quite a few sexual libertines of the Andalusian period!

Surprising that this book ends in the 1100s: surely there were classical Arabic poetesses in the early modern era too? And what about modern writers who use classical Arabic? Might’ve been better to see the continuities rather than to have all these anecdotes ascribed to anonymous women or names whereof we know nothing. But those verses survive for a reason too: the scent of lavender in a child’s hair; a jewelled mourner at a grave refusing to wear anything but what her lover beheld her in.

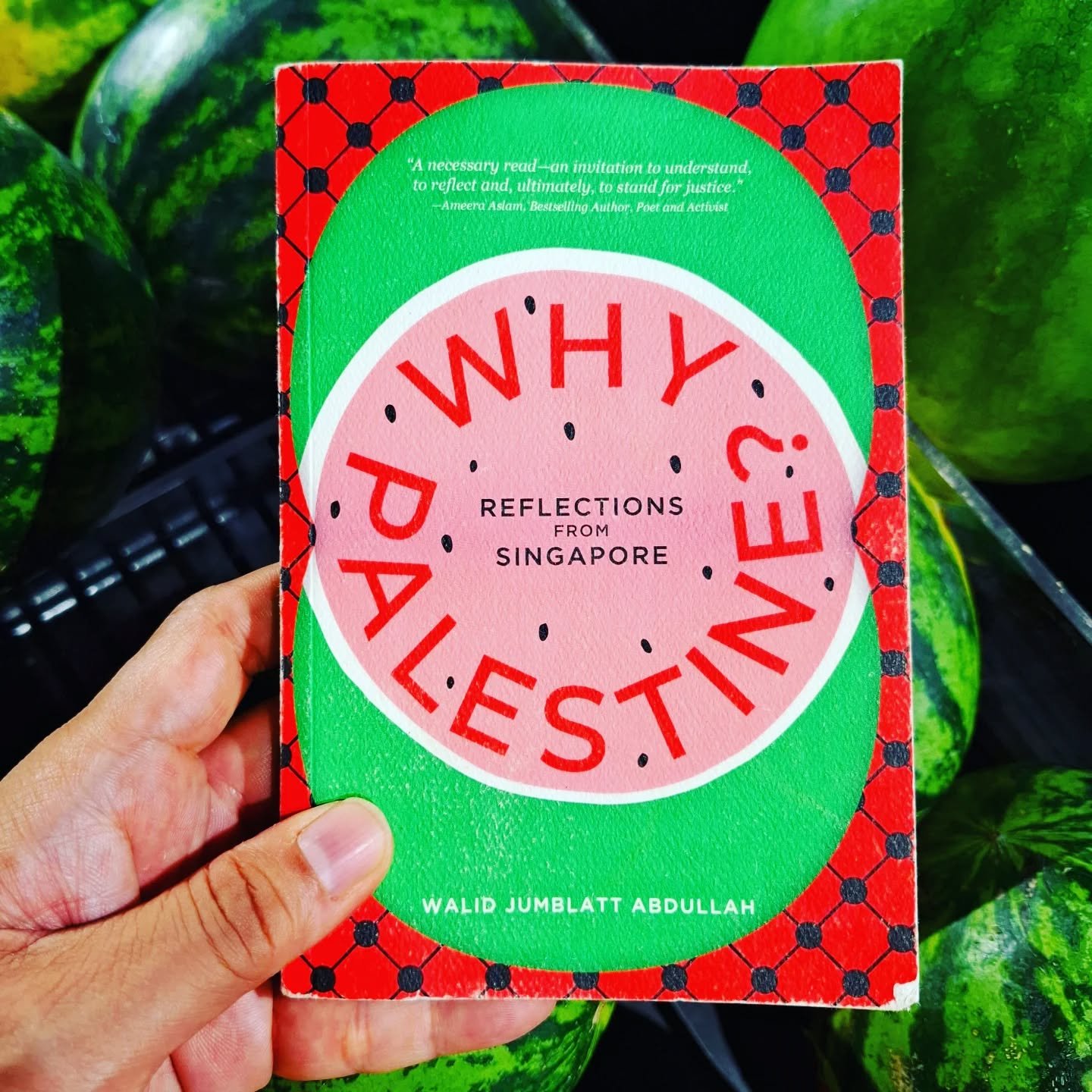

Why Palestine?, by Walid Jumblatt Abdullah

Ethos Books, 2025

Authored by the political science prof behind the web series Teh Tarik with Walid, this is a series of six essays arguing why Singaporeans should come out against the Israeli genocide in Palestine. Honestly old news to most of my friends—for a lot of it he’s just debunking Zionist talking points, e.g. “Why don’t they just migrate?”, “Isn’t this about religion?”, and coming out as rather more conservative than myself, e.g. he does condemn Hamas’s violence on 7 October 2023, whereas I view it as a legitimate act of insurrection against an occupying force.

Where this gets interesting is Walid’s specific POV as a Singaporean speaking to Singaporeans: he not only points out the absurdity of “Could Gaza have been Singapore?” by talking about Israel’s chokehold on the entry of supplies into the territory (strangely, he doesn’t mention the fact that Israel was bombing infrastructure way before 2023), but also the way Singapore is used in the global imaginary, with Djibouti, Rwanda, Panama, Vietnam, El Salvador, Cambodia and Georgia all having once been touted as being alternate versions of our nation. He also champions the legacy of Dr. Ang Swee Chai (including the strangeness of Palestine being the cause that ended her effective exile), and outspoken actor Oon Shu Ann. And vitally for Lee Kuan Yew-trained pragmatic Singaporeans: the importance of holding on to hope. “If the Palestinians themselves haven’t given up hope, what right have we?”, he says, quoting Dr. Ang.

There’s lots more stuff I feel he could’ve written about—how Singapore’s historic ties and parallels with Israel do not mean we have to defend its foreign policy, plus the actual voices of Palestinians (whom I believe he’s talked to). And it’s kinda egregious how little he talks about the arrest of Kokila Annamalai, Siti Amirah Mohamed Asrori, and Sobikun Nahar for organising a delivery of pro-Palestinian letters to the Istana.[3] (Sure, you could say this is because he finished his draft in December 2024, but other friends point to his documented hesitation in endorsing activism as proof that he’s way too moderate to be counted on as an ally.)[4]

Nevertheless, this little book remains pretty damn important as a physical document of how, in a time of genocide, Singaporeans were responding, maybe not as much as we should’ve or could’ve, but still trying to make the world a less horrifying place.

Endnotes

[1] Notably, over 360 Palestinians have been killed by Israeli forces in Gaza since the “ceasefire”. See Seham Tantesh, Julian Borger and Emma Harrison. “‘Bloodshed was supposed to stop’: no sign of normal life as Gaza’s killing and misery grind on.” The Guardian. 6 December 2025.

[2] To learn more, see “Leila Majnun – one of S'pore's earliest Malay feature films.” NLB, 2014. https://www.nlb.gov.sg/main/article-detail?cmsuuid=8413c59a-9d05-4574-b979-19eb513d8e4e

[3] For a summary of this saga, see Lydia Lam. “Trio acquitted of organising pro-Palestinian procession to Istana.” Channel News Asia, 21 October 2025. https://www.channelnewsasia.com/singapore/three-women-pro-palestinian-procession-istana-acquitted-5414691

[4] Check out his essay co-authored with Emily Perera, “(Cautiously) Embracing pro-Palestinian activism in Singapore: civil society in illiberal regimes.” Asian Journal of Political Science, 33(1), 2025, pp. 122–139. https://doi.org/10.1080/02185377.2024.2416130

Ng Yi-Sheng (he/him) is a Singaporean writer, researcher and LGBT+ activist. His books include the short-story collection Lion City and the poetry collection last boy (both winners of the Singapore Literature Prize), the non-fiction work SQ21: Singapore Queers in the 21st Century, the spoken word collection Loud Poems for a Very Obliging Audience, and the performance lecture compilation Black Waters, Pink Sands. He recently edited A Mosque in the Jungle: Classic Ghost Stories by Othman Wok and EXHALE: an Anthology of Queer Singapore Voices. Check out his website at ngyisheng.com.

In Taiwan Travelogue, ‘twinned souls… are at once lost, but also found, in translation.’ A review by Eunice Lim.