A Colonial Taiwan Lost and Found in Translation

By Eunice Lim

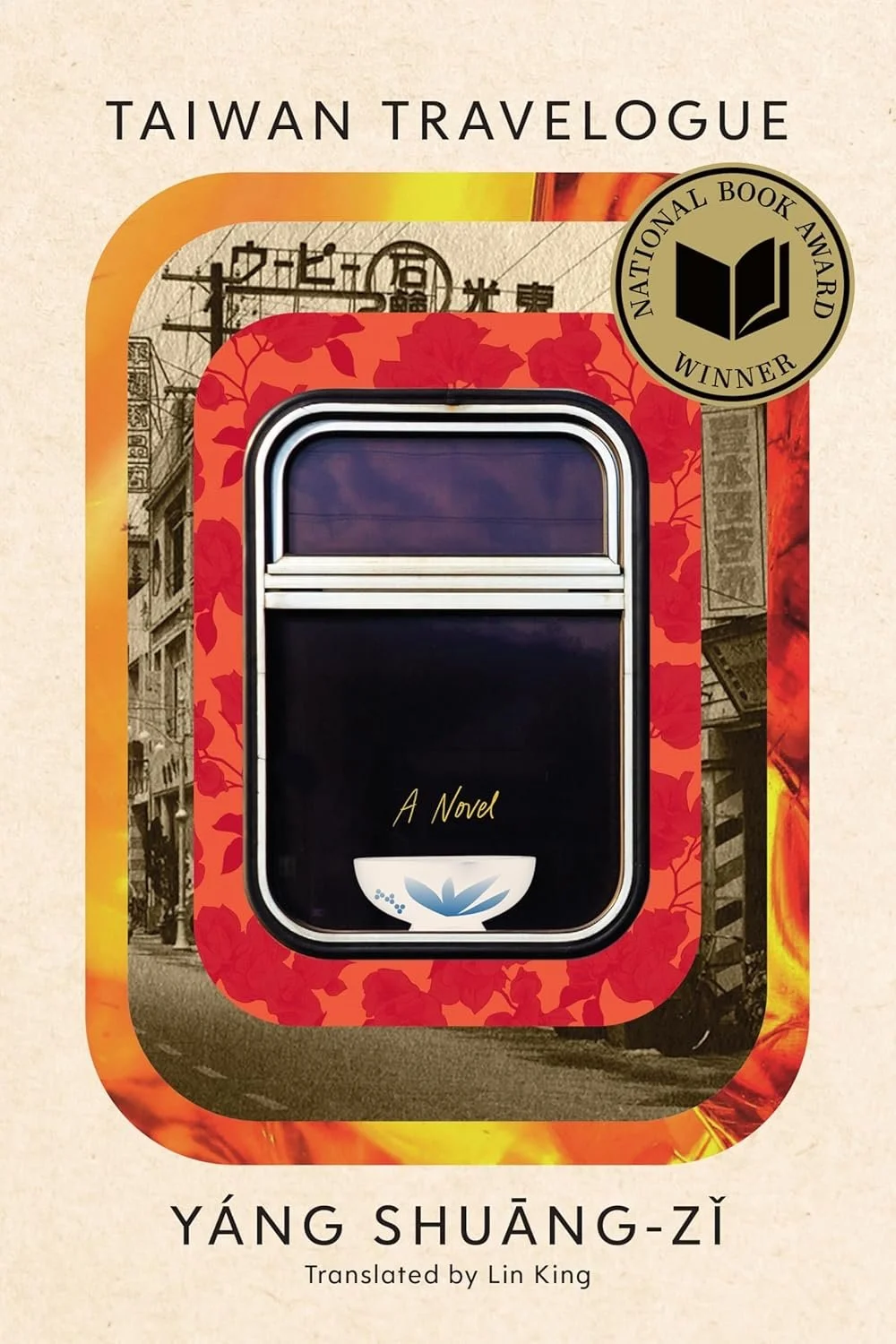

Review of Taiwan Travelogue by Yang Shuang-zi (Minneapolis: Graywolf Press, 2024). Translated from Chinese by Lin King.

Taiwan Travelogue is explicitly a novel about an accomplished Japanese woman writer’s culinary travelogue through late 1930s colonial Taiwan. Implicitly, it explores the female intimacies between the novel’s Japanese unreliable narrator, Aoyama Chizuko [1], and her Taiwanese islander interpreter, Wáng Chiēn- hò (Ông Tshian- hoˈh in Taiwanese, Ō Chizuru in Japanese). Set during the Japanese occupation of Taiwan, a period in which ‘Taiwanese Islanders were second-class citizens compared to Japanese Mainlanders’, the social and political circumstances that form the backdrop of the two women’s relationship cast a significant shadow over their interactions.

It’s hard to ignore, for example, the social and political implications when Chien-ho is introduced to Chizuko neither by her Taiwanese Hokkien birth name nor her Chinese name, but by her Japanese name of Ō Chizuru, a name she adopts as a result of the occupation. Having deliberately distanced herself from the imperialist ambitions of the Empire of the Sun by turning down offers from Japanese publishers to pay for her travels in exchange for articles promoting Japan’s Southern Expansion Policy, Chizuko fancies herself an innocent Japanese mainlander and modern woman of reason. As a result of this self-perception, Chizuko is unable to recognize her apparent colonial privilege and complicity, failing time and again to understand why her many attempts at befriending Chizuru have caused distress and discomfort for the latter. This is the central conundrum facing our two female protagonists, who are kindred spirits inextricably mired in the social and political trappings of their time.

Before unpacking the women’s complex relationship, it is important to clarify that despite the many formal characteristics of Taiwan Travelogue that might give an unsuspecting reader the impression that it is a non-fictional travelogue written by an actual celebrated literary figure called Chizuko, the work is a fictional, self-reflexive work of meta-translation. Although the novel references an original Japanese version in 1954, a first Mandarin translation in 1977, and a new English translation in 2015 (notably distinct from the 2024 “copy” that the reader is reading) in the conventional paratextual space where one typically expects front and back matter, the bulk of the referenced translations, editions, and people do not actually exist. Yang Shuang-zi (楊双子) is a pen name that represents the actual Taiwanese author Yang Jo-tzu (楊若慈) and her late twin sister Yang Jo-hui (楊若暉). The Yang sisters shared many literary and artistic pursuits, and the latter, who passed away from cancer in 2015, was interested in Japanese history and translation. Taiwan Travelogue poignantly reflects their interests and thus effectively functions as a co-creation of the two sisters. Despite the novel’s extensive fictional narrativization of its own publication history, it was originally published in Chinese by SpringHill Publishing in 2020. A Japanese translation was released in 2023, and Lin King’s English translation of the Chinese original is the version that is being reviewed here.

Narrative and structural boundaries between fiction and nonfiction are blurred in a dizzying postmodernist frenzy that recalls Vladimir Nabokov’s Pale Fire (1962), with King, the actual translator of Yang’s novel, contributing a translator’s note alongside the fictional translator and character of Wang Chien-ho. This ingenious paratextual dance between real and fictional authors, editors, translators, characters, and scholars does not merely reiterate the long-exhausted death pronouncement of the author. Instead, Taiwan Travelogue is a delightful meta-fiction and meta-translation that enlivens the lives of all those involved in its making, affirming and advocating for the inherently collaborative nature of storytelling and inviting readers to plunge into its densely woven trail of real and fictional translations, afterwords, and notes. Yang’s impressively crafted novel and King’s masterful translation co-deliver a beautifully written work brimming with memorable imagery, such as when ‘boys wearing student caps’ are clustered around a vendor selling lóo-bah rice ‘like butterflies sharing a petal’. The descriptions of the two women’s travels through colonial Taiwan also offer glimpses of a past when wheel cakes, a Japanese snack introduced to Taiwan during the colonial period, were still known as taiko manjū and were sold by vendors on Shōsei street alongside other Taiwanese street foods.

With an insatiable appetite for the culinary delights of the Taiwanese islanders, Chizuko relies on Chizuru as the intermediary native informant and interpreter. Through the latter’s bittersweet and somewhat grudging efforts, Chizuko and the novel’s readers gain access to a wide range of mouth-watering local food like kue-tsí (roasted seeds) and bah-sò (braised minced pork). The title of chapter two, ‘Bí-Thai-Ba'k / Silver Needle Vermicelli’, for example, describes a savory rice noodle dish ‘served with pork bone broth, topped with minced pork stewed in soy sauce and chives’. The novel’s chapters are also helpfully titled and structured after the dishes that are being narratively served. Foodies and food historians will likely appreciate this aspect of Taiwan Travelogue’s mapping of Chizuko and Chizuru’s culinary passage through colonial Taiwan.

Just as food serves as Chizuru’s convenient distraction from the more discreet political tensions that are simmering throughout colonial Taiwan, food is also how these tensions are gustatorily expressed and accounted for. Chizuko scoffs at ‘the idea of using [her] pen as a weapon for war’, but fails to recognize the condescending soft power that she continues to hold over Chizuru and how her appetite for Taiwanese food stems from and continues to perpetuate the Japanese imperialist fantasy of uninhibited possession, control, and consumption. An inconspicuous footnote detailing the modification of short-grain japonica rice by Japanese agricultural scientists so that they could grow in Taiwan’s climate and the assumption that Chizuko would prefer to eat at a ‘restaurant of Taiwanese cuisine catered toward Mainlander guests’ hint at the territoriality at the heart of the colonial enterprise and the discriminatory biases that govern much of the interactions between mainlanders and islanders respectively. Chizuko’s relentless efforts to befriend Chizuru and her insatiable enthusiasm for Taiwanese islander food that she exoticizes are ultimately weak salves to the wounds of imperialist violence wrought upon the Taiwanese land and its people. The former’s unwillingness to acknowledge the reality of her and Chizuru’s hierarchical differences is a recurring source of frustration and unease for the latter, who repeatedly expresses a preference for professional distance and eventually declares that it is ‘impossible for a Mainlander and an Islander to share a friendship of equals.’

Of the many achievements of Taiwan Travelogue, its sixth chapter – ‘Tang Kue Tê / Winter Melon Tea’ – is, in my opinion, the novel’s crowning one. During a visit to the Tainan County First High School for Girls – a school that is distinct from the Second High School in that it has more students with mainland citizenship – Chizuko and Chizuru hear about a mysterious conflict between two students there – Ōzawa Reiko of mainland citizenship and Tân Tshiok-bi of island citizenship. The two students become the young narrative foils to the primary protagonists of Taiwan Travelogue, and it is through Chizuko’s and Chizuru’s informal and impromptu investigation into what really happened between the two students that the novel arrives at its crucial inflection point. Having contemplated and discussed the students with Chizuru, Chizuko privately considers in the narration how Chizuru and herself might, too, be ‘characters in a shōjo romance’. Whether this is an appropriate or welcome comparison for Chizuru does not seem to cross Chizuko’s mind. Yang is known for including yuri themes in her work, and it is the novel’s meditative exploration of the sociopolitical possibilities and limitations of female kinship, intimacy, and affinity that is its greatest selling point.

In the same chapter, Chizuko and Chizuru also compare themselves to Arthur Conan Doyle’s mystery-solving duo, Sherlock Holmes and Doctor Watson. These cross-genre character parallels that have been strategically introduced in the middle of the novel invite readers to rethink Chizuko’s and Chizuru’s characters for the rest of the novel, while also persuasively inviting us to consider how established genres and characters have the potential for collaborative rewriting, reinventing, queering, and boundary-crossing. In an intensely self-reflexive, meta-fictional novel like Taiwan Travelogue, this invitation to rethink rigid boundaries is, I believe, also an invitation to rethink international, historical, and interpersonal ones, to discover new possibilities for being, relating, and engaging with others in the world.

With its entwined exploration of Taiwanese and Japanese history, food, and womanhood, Yang Shuang-zi’s Taiwan Travelogue would be a compelling and eye-opening read for many readers, especially those interested in a deeper understanding of Taiwan beyond the current headlines involving its escalating tensions with China. A sophisticated exploration of insider-outsider dynamics, this novel is a must-read for anyone trying to navigate intense sociopolitical or/and interpersonal upheaval and strife. Between these pages of culinary delights and adventure, you will likely find many opportunities for literary comfort, recognition, and reflection, whether you see yourself as more of a Chizuko or a Chizuru. I suspect most of us will see a little of ourselves in both characters, twinned souls caught in sociopolitical crosshairs who are at once lost, but also found, in translation.

Endnotes

[1] It is worth noting that since the novel’s narrator is Aoyama Chizuko, she is mostly referred to by the other character in the novel as “Aoyama-san”, but to avoid confusion, I have chosen to refer to Aoyama Chizuko as Chizuko throughout my review. As the narrator of the novel, Chizuko also refers to Chizuru as Chi-chan throughout the novel.

Born and raised in Singapore, Eunice Lim grew up watching Taiwan’s Minnan dramas with her family and Taiwan’s Mandarin idol dramas with her friends. Having visited Taiwan a few times, she fondly remembers the steaming bowl of Yang Chun noodles she had near Taipei’s Lungshan Temple. Eunice is currently a Lecturer at the University of Nebraska-Lincoln. Eunice has published journal articles in ariel: A Review of International English Literature, Global Storytelling, and Antipodes. One of these articles is about a Taiwanese drama that she has watched more than ten times. That Taiwanese drama has made her cry every single time.

#YISHREADS returns with the theme of sequels, you know, that genre that everyone loves to hate.