Felix: The Comics, January 2026

By Felix Cheong

A new year, a new hope. And a new column.

Welcome to Felix: The Comics, a space dedicated to reviews of graphic novels. It will be published in the last week of January and July.

Why graphic novels? In case you haven’t heard: sales of graphic novels have risen over 100 percent since 2019, making graphic novels the third bestselling genre in North America, behind general fiction and romance. That’s according to a 2024 report in Library Journal [1].

Another 2024 article in The New York Times showed that one in four books sold in France is a graphic novel (including nonfiction works) [2]. Even university presses—bastions of serious (read: “snobbish”) books—are hopping on the bandwagon, releasing graphic history books to appeal to a wider readership [3].

In Singapore, graphic novels are coming into their own too. The Singapore Book Awards and the Singapore Literature Prize now have a category just for comics and graphic novels.

The correct question is not “why graphic novels?”, but “why did such a column take so long to materialise?” But here it is; better late than sorry!

In line with Tessa Hulls’ Feeding Ghosts landing the Pulitzer last year (only the second graphic novel to do so after Art Speigelman’s Maus in 1992), I decided to kick off the column with four graphic memoirs by women you should check out.

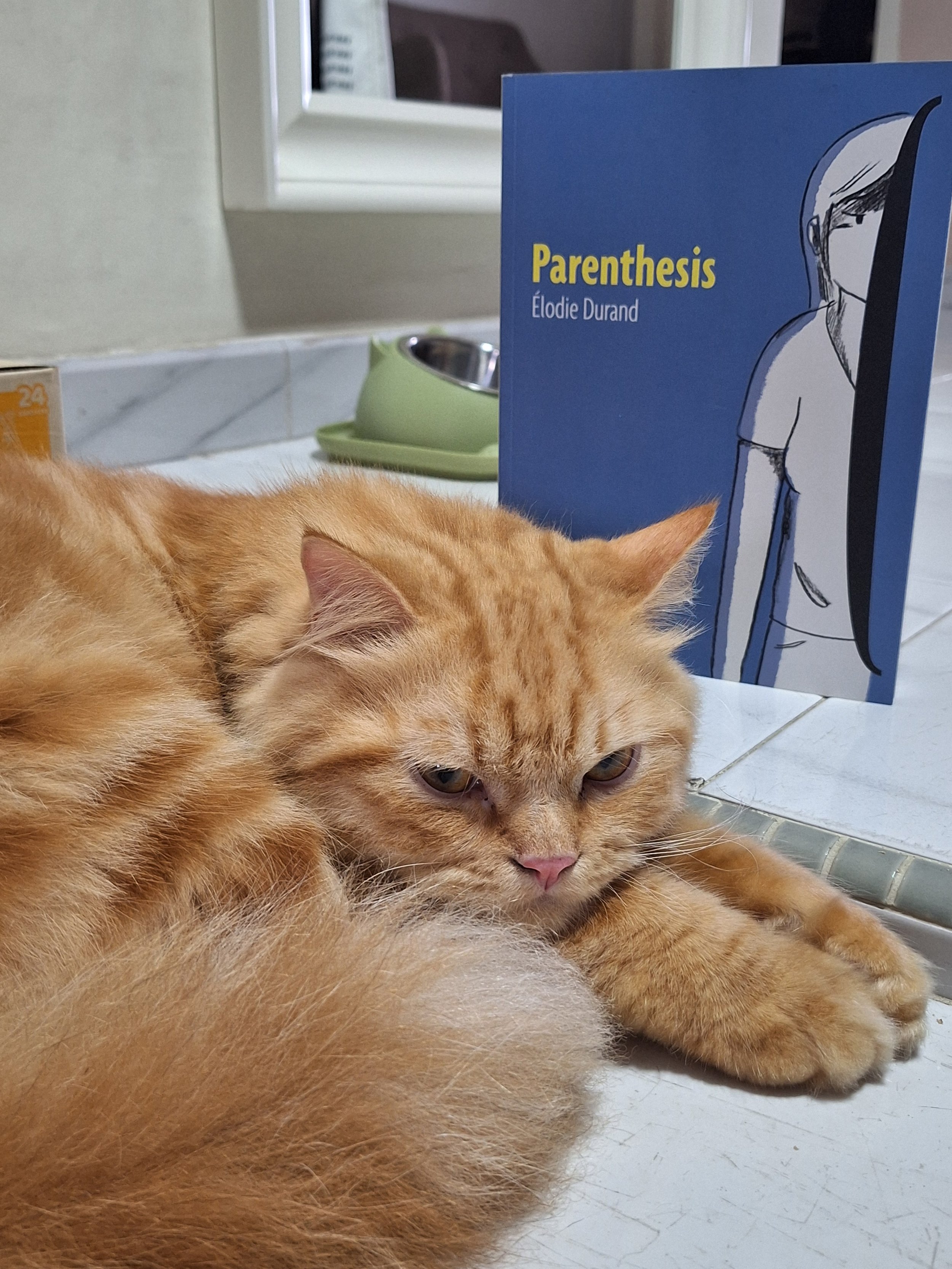

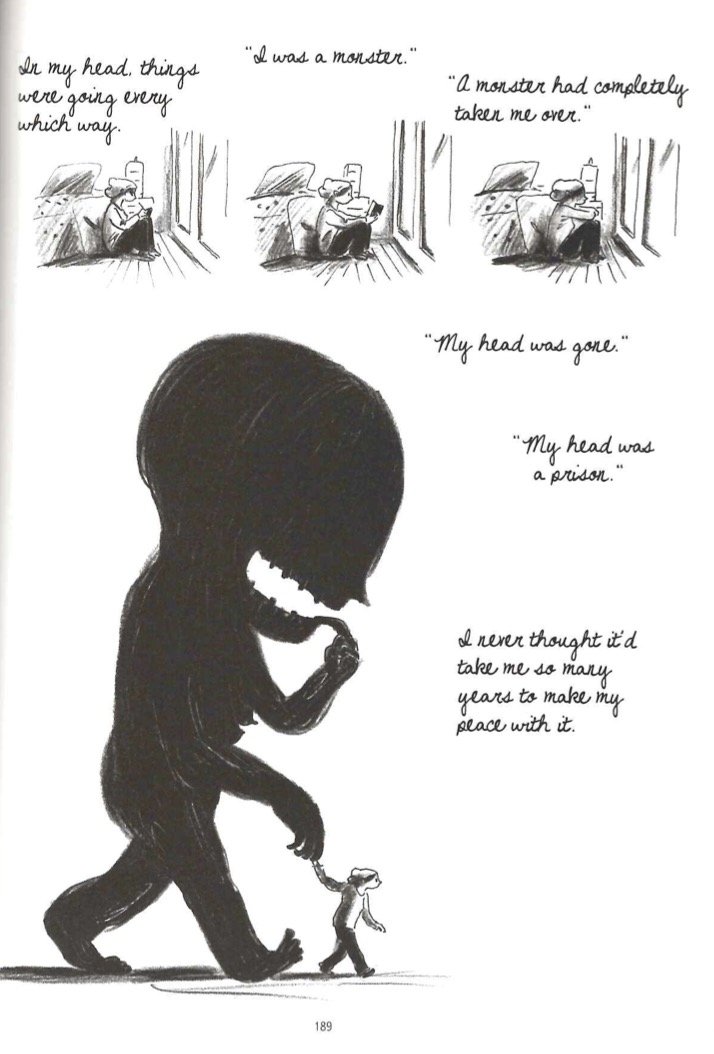

Parenthesis, by Élodie Durand

Top Shelf Productions, 2021

What if you black out. And bl—out. And—out.

That’s the state French cartoonist Élodie Durand found herself in in her early twenties. Parenthesis chronicles a body at war with itself: with an epilepsy diagnosis revealed to actually be a brain tumour that had blanked out chunks of her youth.

The title pulls a neat e.e. cummings trick. Does it refer to Durand being trapped inside the parentheses—those blackout spells, later dulled by medication? Or is she outside them, amputated from the world whenever her mind slips, sliding away? Either way, it effectively sums up her lived experience.

To wrest back control of her life, Durand turns to drawing—expressive, charcoal artwork, with heavy shadows standing in for places her memory can’t access. When the page darkens, you feel your mind cowering in the dark with it.

Durand’s storytelling often feels cinematic. Repeated panels—such as a page dedicated to her various stages of sleep—read like film reels. And despite the life-or-death stakes, she treats her condition with mordant humour—most memorably by rendering herself as a giant disembodied head, while her doctors are Lilliputians scrambling to scale it.

The book does falter, though, in its repetition of her blackout episodes. Three, the reader gets the point. Anything more—becomes a liability. Interviews with her parents patch the missing time, but this explanation feels like closing the barn door after the mind has already bolted.

A riskier approach would have been to leave those gaps unfilled, throwing the reader into the deep end of her confusion. Then her persistent question—What happened?—becomes our own.

Originally published in French in 2010, the English translation of Parenthesis was released in 2021.

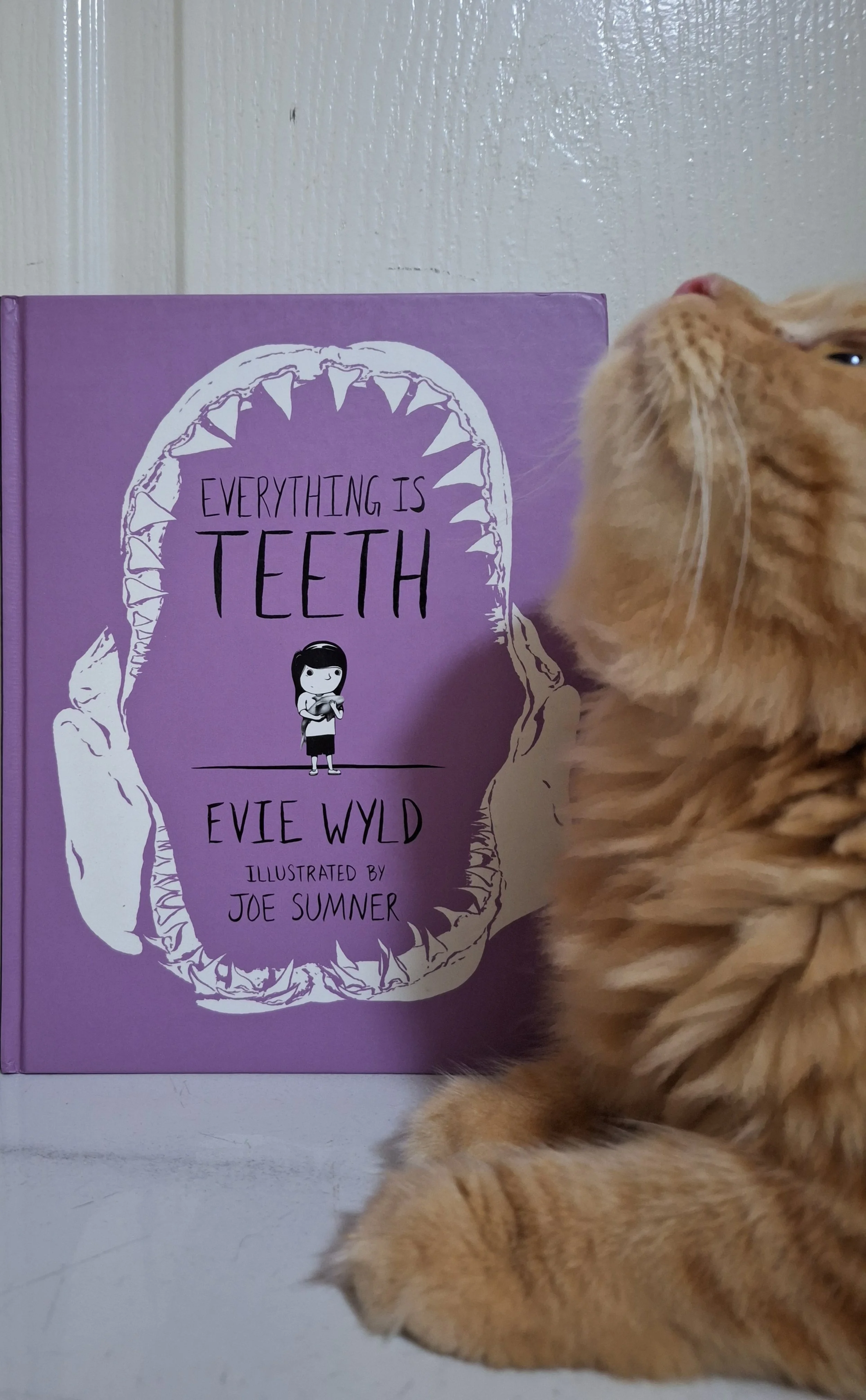

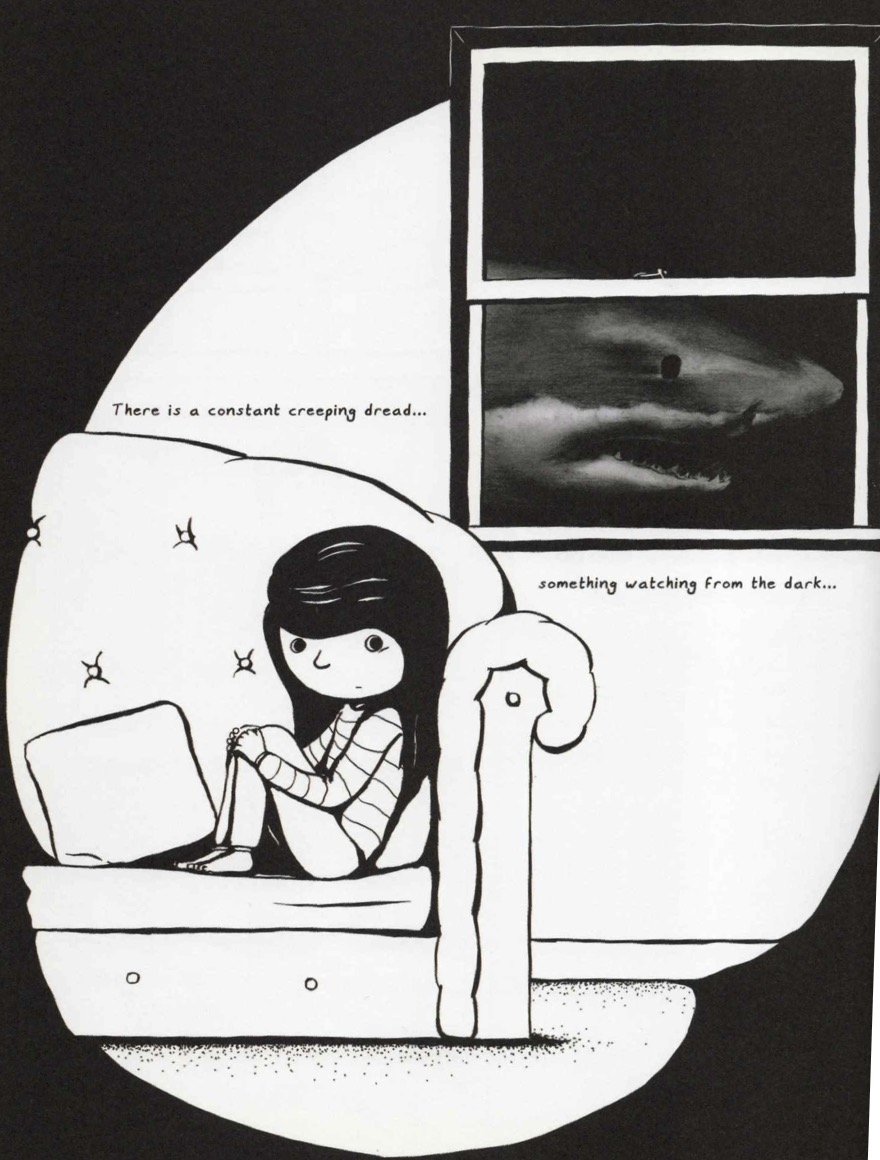

Everything is Teeth, by Evie Wyld, illustrated by Joe Sumner

Pantheon Books, 2015

Everything Is Teeth is a graphic memoir with teeth marks. And very large ones too.

British writer Evie Wyld replays memories of childhood summers spent in Australia through a recurring terror: a shark. It stalks her in stories told by her family, in the rearview mirror, alongside her, and even through a few scenes recreated from Jaws (1975). It is everything everywhere all at once.

The shark is, of course, that monster under the bed that children cry “Wolf!” about when they can’t articulate their fears. Here, Wyld isn’t so much concerned about sharks as how the fear of them fin(d)s its way into her psyche.

And in what a visceral way Joe Sumner’s artwork has rendered her theme. While the characters are drawn child-like, with a limited pastel palette, the sharks are something else altogether. They’re photograph-realistic—nay, hyper-realistic. The effect is at once unnerving and unsettling in a Damien Hirst way.

One criticism of the book is Wyld’s unfamiliarity with the comic book form. While her prose is poetic, it is all too often submerged under descriptions the artwork could have taken care of. An example: she describes her brother riding rodeo on a shark carcass, but the panel visualises the same thing. Instead, her line could have slathered another layer of “show, don’t tell”. And, other than the occasional speech bubble, the characters hardly speak, except through indirect speech, as if they are flotsams in her past.

Nonetheless, it’s still a biting read (couldn’t resist one last pun). And relatable too, since I was also chased by imaginary sharks in my childhood (thank you, Spielberg, for giving me a complex!).

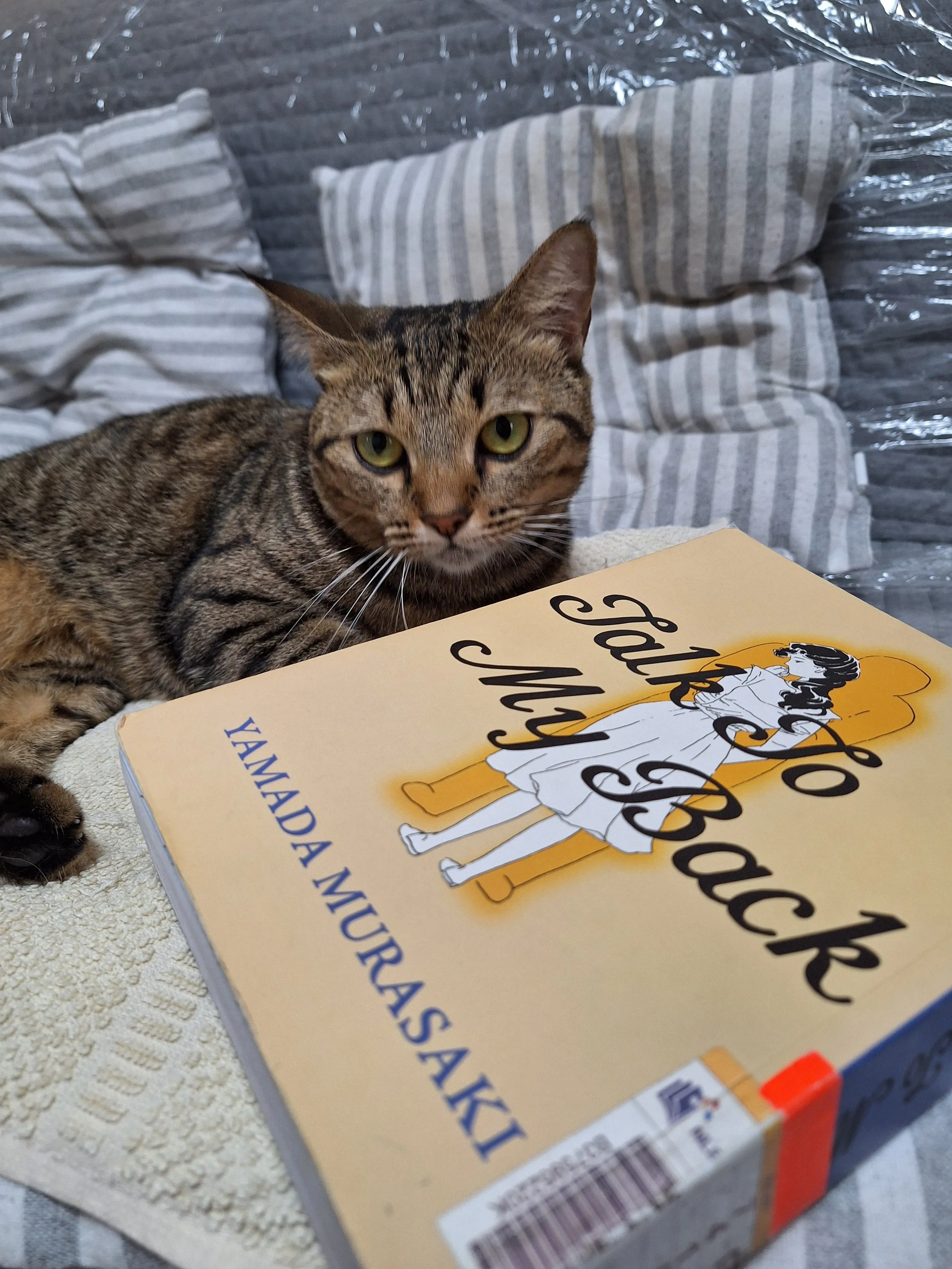

Talk to My Back, by Yamada Murasaki

Drawn & Quarterly, 2022

First published as short comics in the 1980s in alt manga magazine, Garo, Talk to My Back is Yamada Murasaki’s takedown of Japanese male hegemony. Fictionalising herself as Chiharu, a housewife with three kids—two daughters and a husband—Murasaki sketches mundanity raring to break free.

There are vignettes of her tending to house chores, cooking for and feeding the family, sprinkled generously with lamentations about why her life isn’t more exciting. It doesn’t help that she’s matrimonially handcuffed to a male who thinks women are only good for the kitchen and bedroom.

As surely as dawn follows night, Chiharu finds herself a job and eventually, out of the marriage. (Her divorce was finalised in 1983.)

But the turning point is ever so gentle. There are no big dramatic fights, no meltdowns with speech bubbles where she rails against society. What you get instead are lived-in moments that gather quiet strength and velocity over time. And when the breakup happens, it’s earned and inevitable.

Like her story, Murasaki’s art style, while obviously manga, is also bird-like. Sometimes, she avoids filling in her own features, as if suggesting she’s not fully formed yet as a person.

Interestingly, she remarried in 2002, to former Garo deputy editor, Shiratori Chinatsu, 17 years her junior. Talk about turning the tables on male hierarchy!

Murasaki passed away in 2009. The English version of Talk to My Back, translated by Ryan Holmberg, was published only in 2022 [4].

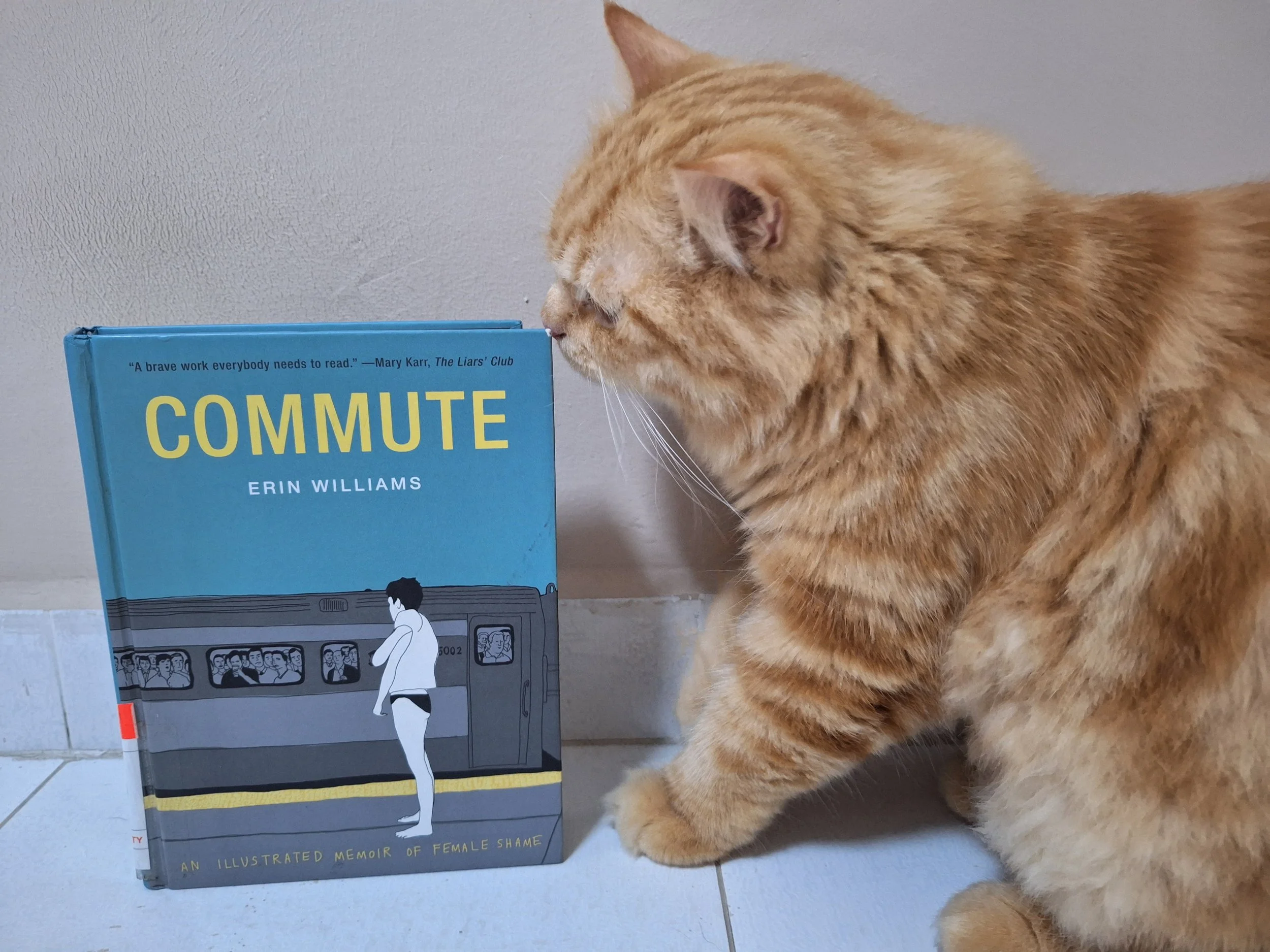

Commute: An Illustrated Memoir of Female Shame, by Erin Williams

Abrams ComicArts, 2019

Commute is what you might come up with if you space out with pencil and paper on the commute to work—random access memory, a stream of consciousness gushing into sudden insights.

That’s the premise behind American cartoonist Erin Williams’ first book. It is unashamedly confessional—I mean it in the best possible way—raw and, more interestingly, a ream of scattered thoughts that soon coalesce into a meditation on female shame (hence the subtitle).

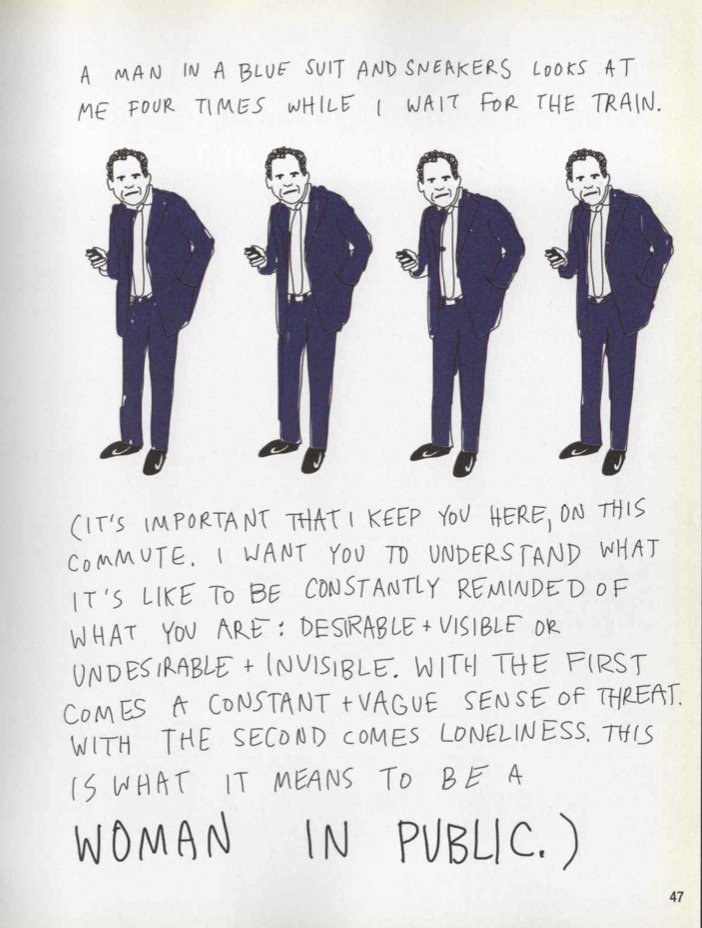

As Williams drifts from drawing regulars on the train (including a creepy guy who male-gazes her) to her own body, she’s reminded of one-night stands, alcohol benders and (spoiler alert) a sexual assault that was never reported to the police. But such shocks are never for shock’s sake. They require courage to speak and argue about, and finally come to terms with.

While Williams’ artwork flows with the tide of her narrative, it often looks more like a sketchbook, driven, not by chronology or an overarching story, but her train of thought. And it’s at times funny, with visual puns and asides that play off the text.

Best consumed in small doses during—what else?—a train ride.

Endnotes

[1] “Graphic Novels Broaden Their Appeal.” Library Journal, 9 September 2024. https://www.libraryjournal.com/story/graphic-novels-broaden-their-appeal-lj240909

[2] “A Boom in Comics Drawn from Fact.” The New York Times, 24 January 2024. https://www.nytimes.com/2024/01/24/books/french-nonfiction-comic-books.html

[3] Oxford University Press, for instance, has 20 graphic history books with esoteric titles such as The Great Hanoi Rat Hunt: Empire, Disease, and Modernity in French Colonial Vietnam (2018).

[4] Holmberg also wrote an extensive foreword on Murasaki which, in true Japanese book style, is placed at the back of the book.

Felix Cheong is a Singapore writer who has published 32 books across different genres, including poetry and fiction. He has also written 10 graphic novels, of which Sprawl was named by Comics Beat as one of 75 most anticipated reads for summer 2022. Two of his graphic novels have also been shortlisted for the Singapore Book Awards. Recipient of the National Arts Council’s Young Artist Award in 2000, Felix has been invited to writers’ festivals all over the world, including Edinburgh, Austin, Sydney, Christchurch and Ubud. He is currently the Programme Leader of Singapore Literature and Creative Writing (Prose) at the Singapore University of Social Sciences.

#YISHREADS returns with the theme of sequels, you know, that genre that everyone loves to hate.