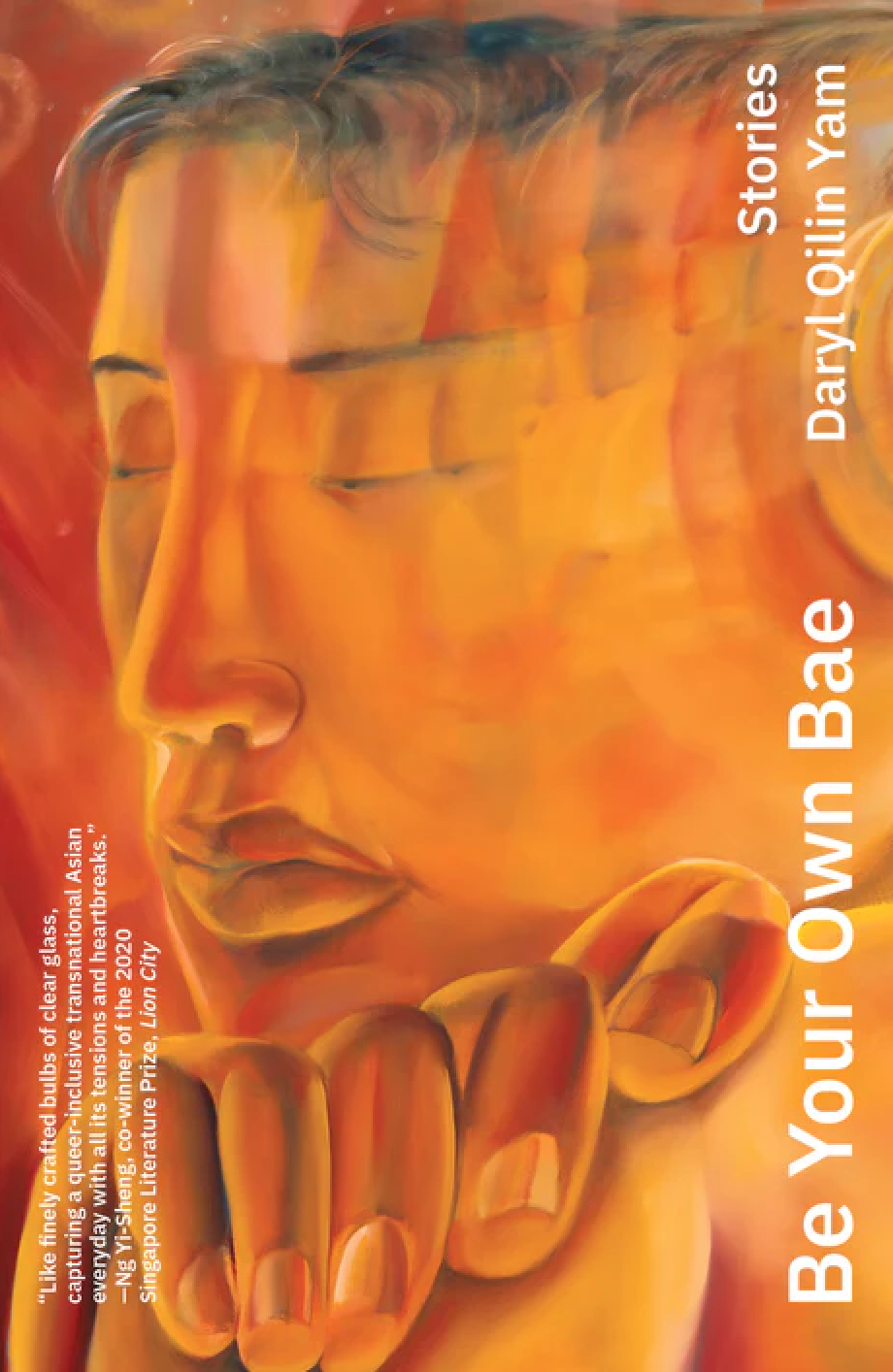

Review of Be Your Own Bae by Daryl Yam (Singapore: Epigram, 2024)

By Melody Lee

Daryl Yam takes his readers through landscapes lightly tinged with magic realism in Singapore and other cosmopolitan cities in Be Your Own Bae as he paints a portrait of the artsy and queer millennial soul. Through the characters, we get a sense of how a particular group of Singaporean millennials — well-educated, upper middle class, jiak kantang — sees the world.

Yam, a millennial himself, is a Singapore-based writer of two published novels and one novella; Be Your Own Bae is Yam’s fourth book and first short story collection. The collection is structured in twelve stories; characters recur across different stories, giving a sense of separate worlds within the same universe, like a city of people going about their own lives without intersecting with one another. The first world features a quartet of querulous hipster friends who share a love of Bon Iver; the second contains a woman and two men inexplicably bound to the Lorong Chuan canal; the third features an introvert learning about love and grief in the aftermath of a partner’s death; while the last has a fictionalised version of the author recounting his past relationships.

I highlight millennial because that is what jumps out at me: the mannerisms, concerns, and attitudes are painfully familiar, speaking as another member of this generation who has experienced the pre- and post-smartphone world. In “The Wolves, or Have You Ever Read Tao Lin?”, part of the first world with the hipster quartet, Yam captures the relatable distractibility of a millennial adult as Caleb’s attention flickers back and forth between his date newly met from a dating app, his phone messages, his anxieties over recent childish spats with his friends, and the exclusive Bon Iver gig that is about to start in a bar at Dempsey Hill. I love how that story overloads the reader with these events all competing for attention, then beautifully focuses when the music starts: Yam takes us through the ascending arc of a concert, conjuring magic from music and crowd coming together to silence life’s constant background rumble.

But the crowd around them showed no sign of dissipating at all, no sign of dispersing or heading back out into the streets; Hongsik had to hold Caleb’s head in his hands and ask him what time it was, with a smile that bordered on mania, euphoria. “What time is it!” he asked Caleb, giddy and dizzy with the love, and the excitement, and the rush of it all, a rush that reached the doors only to turn back into the room, into the air that circulated between him and his friends, wherever the hell they were, and Caleb had to tell him that he didn’t know, dude, he didn’t know. He would never, ever know. Oh my god.

Yam’s attempt to give us a non-cliched glimpse into the lives of millennials as new adults is commendable. Characters struggle with relatable uncertainty on many things: romantic love (its pursuit; its feeling), friendships (how to maintain them; how to support your friends), families (how to communicate with a depressed uncle), their place in the world, the meaning in the work they do. With the hipster quartet, Yam showcases a particular manifestation of millennial friendship, layering the set of stories with perspectives from different members and interactions between the various permutations of pairs in the clique. The juxtaposition of their banal moments — quibbling about the veracity of an anecdote, watching The Shining together for the seventh time — with their earnest and sometimes awkward attempts of support at times of despair is particularly compelling. “Thing Language” is a great example of this tension at play: the clique visits a modern art exhibition at Goodman Arts Centre, tries to comprehend dick art next to a fresh pool of Caleb’s vomit, and deals with Sof’s existential crisis and breakdown as she struggles with inspiration as an emerging artist.

Sof caught further snatches of the interview on her way out. “I can’t say that we’re in a relationship,” the Balinese artist had said. “If we’re in a relationship with anything, it’ll have to be a relationship with space, with distance. We make love across the earth. Our love,” she wanted to stress, “is metaphysical.”

Adulthood brings with it a greater probability of hard life lessons; Yam’s portraits of characters coping with loss are stirring, like the one of Vern in “Painful”, as he and his ex-partner’s sister, Zara, pick up the pieces of their lives after the death of his ex-partner. The story ends powerfully with what appears to be an earthquake, in the liminal space between reality and metaphor:

And the more the sound builds the more my flat begins to shake: everything’s shaking, literally—bed, lamp, closet, window. Even the very floor. It’s a tremor, from some kind of earthquake, happening somewhere beyond my comprehension—and the effect of it is immediate, which is to say that I’m already experiencing it from a distance, a distance not of space but of time. I can’t help it. I’m already seeing a past version of myself, one that is still hurt, and grieving, and afraid of dying alone; I’m picturing him looking forward to the touch of Zara’s hand, two people once as close as siblings, brother and sister, wondering how either of them will withstand it, the rupture.

Yet despite the myriad of characters that populate the collection, there is a certain homogeneity in their voices; little differentiates them other than details in their backstory. Characters seem to come from the same upper-middle socioeconomic class: jetsetting is taken for granted (almost every story either features Singaporean characters in a foreign first-world country or recounting experiences in those places), and characters never worry about money or make reference to the drudgery of work. To be clear, I do not think that a story needs to have poverty porn, but the complete absence of practical concerns, nor any self-aware remark about privilege, in an entire collection feels jarring, especially considering the challenges in having a full-time career in the arts in Singapore, of which at least four characters have chosen.

With nothing grounding their motivations, characters can feel self-indulgent, impulsive, and whimsical, as if the be-all-and-end-all of doing something is what they feel about it. Members of the hipster quartet throw tantrums and slippers from overhead bridges; Clara from “Some Place/Some Time” meets a man years after their first date in another country, returning to her apartment for sex after he shares that he is newly married. Little is said about internal conflicts or obligations to others, and that is the trend across the collection, conveying a solipsism I find alienating.

This sterility of voice infects that of setting as well: the Singapore in Yam’s stories feels generic, and even as Yam goes as far as to centre a set of stories around a Lorong Chuan canal, I don’t feel a strong sense of place, one that is different from the idea of a canal I have in my mind. For me, that reduces the effectiveness of the surreality that Yam tried to infuse in this set: the atmosphere isn’t convincing enough to conjure a sense that the impossible is possible. As a result, events that happen feel random and lacking in significance.

There are a few instances when characters are confronted with events that threaten this sense of invulnerability, having overcome all practical concerns. Some of them are specific to being gay in a hostile world: the collection is sprinkled with incidents of gay-targeted aggression, such as when Caleb and his boyfriend head to a gay bar in Seoul in “A Film by Hong Sang-soo” only to find its storefront shattered by a homophobe. There are sexual assault incidents: the fictional Daryl strikes up a conversation with a straight-presenting old schoolmate after a party in “Speculative Fiction” only to be surprised by a forced kiss at the end of it; Jonghyuk from “A Dream in Pyongchon” enters into a secret relationship with a fellow university student who ends up raping him and disappearing afterwards. In most instances, the stories rush past the incident to the next event, as if avoiding the emotional reckoning that comes with acknowledging this casual violence. Yam comes closest to having a character confront his pain in “A Dream in Pyongchon”, which takes the form of a written testimony made to an unspecified North Korean authority, but Jonghyuk has to use the vehicle of a dream to talk about it, and even then his emotions are hidden in footnotes deep within the second half of the story. On top of that, readers are told later that it is a story created by another character in the collection, further distancing the reader from the source. These feel like missed opportunities for emotional honesty; instead, Yam seems more comfortable dealing with wonder or metaphysical angst.

For the most part, Be Your Own Bae is an enjoyable read, offering the reader a vicarious glimpse at the conversations and concerns of Singapore’s artistic milieu from the millennial generation. If you are looking for love in this age of dating apps, or a member of the Singapore literary community, you will see yourself reflected in some of the characters, maybe even laugh at their inside jokes; if you are looking for queer representation in Singapore literature, there’s plenty of it in here.

Melody Lee is a full-stack web developer who loves reading across genres, playing indie games, hiking across mountainous landscapes, and climbing plastic holds.

#YISHREADS returns with the theme of sequels, you know, that genre that everyone loves to hate.